Border disputes between Australia and East Timor

The border disputes between Australia and East Timor concerned the Timor Gap , an area in the Timor Sea where there was originally no agreement between Australia and Portuguese Timor about the course of the sea border . Australia made its first agreements with Indonesia , which occupied the former Portuguese colony for 24 years against international law. Several contracts between the independent East Timor and Australia were later to regulate the border and the use of the oil and gas deposits in the region, which were discovered in 1974. However, a dispute over the location of the further processing of the natural gas and an Australian espionage act against East Timor that was uncovered in 2013 led East Timor to suing the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague for the termination of the contracts. In 2018, the dispute ended with the signing of a border treaty.

The demarcation between Australia and Indonesia

As early as 1963, the Australian company Woodside Petroleum received permission from Australia to search for oil in the Timor Sea. Australia could not agree on the border there with Portugal. Australia demanded a border drawing along the end of the Australian continental shelf , Portugal demanded an orientation along the center line between the coasts of Timor and Australia.

In 1972, Australia and Indonesia agreed to draw the border between the two states in the Timor Sea. Australia's maritime border to the north thus only had a gap with Portuguese Timor, the so-called "Timor Gap". In 1975, in the course of the decolonization of East Timor, civil war broke out between the country's parties. The Portuguese colonial administration withdrew and Indonesia began to occupy the border regions. When FRETILIN, which had emerged victorious from the civil war, unilaterally proclaimed independence, Indonesia, with the backing of Australia, invaded the rest of the national territory and annexed East Timor as its 27th province in 1976. This was not recognized internationally. Officially, the area was considered "Portuguese territory under Indonesian administration". In 2020, an Australian court ruled that government documents, such as diplomatic news and cabinet papers about Australia's role during the Indonesian invasion, must remain secret, as disclosure could endanger Australia's security or international relations. Documents that have already become public show that Australia's interest in the oil and gas reserves in the Timor Sea had a decisive influence on its actions.

In a Memorandum of Understanding ( English MoU ) agreed between Australia and Indonesia in 1981, a provisional scheme for fisheries surveillance and enforcement ( Provisional Fisheries Surveillance and Enforcement Arrangement ). The Timor Sea raw material deposits were not part of the declaration, but they provided a basis for other questions about the use of the sea area by drawing the Fisheries Surveillance and Enforcement Line (PFSEL). The PFSEL roughly followed the center line between the coasts of Timor and Australia and was later largely adopted in the 1997 treaty when the boundaries of the exclusive economic zones and for the seabed were drawn.

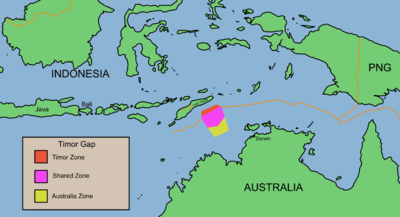

In 1989 Australia and Indonesia signed the “ Timor Gap Treaty ”, which came into force in 1991. In order to avoid disputes about the sea border, the question was simply left out. Instead, three zones of cooperation were created in which both countries wanted to jointly produce oil. In Zone A (on the map in pink) 50% of the tax profits should go to the partners, in Zone B (on the map yellow) Indonesia should receive 10% of the taxes collected from Australia and in Zone C (on the map red ) Australia 10% of Indonesia's taxes. Portugal sued Australia in the International Court of Justice over the Timor Gap Treaty , but the court was unable to hear it because Indonesia refused to attend.

Overall, the demarcation did not follow international law. The northernmost limit of the zones corresponds to the maximum claim of Australia and follows the deepest point of the Timor Trench . Here the Eurasian meets the Australian plate . The Australian claims thus extend over the entire Australian continental shelf. The southernmost border of the cooperation zones is 200 nautical miles from Timor. Under Articles 55 to 75 of the Convention ( English United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea , UNCLOS), the Indonesia in 1986 and joined Australia in 1994, this corresponds to the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of East Timor. If there is a sea area between two states less than 400 miles away, one orientates oneself on the center line, which according to the Timor Gap Treaty represents the border between zone A and B, almost identical to the PFSEL. The border between zones A and C roughly corresponds to an extension of the sea borders according to the 1972 treaty. In part, it runs parallel to the Timor Trench.

The western boundary of Zone A is a line that starts from the mouth of the Camenaça River , while the western boundary of Zone B starts from the mouth of the Tafara River . Both lines meet on the center line between Timor and Australia. Contrary to some claims, the western border does not correspond to the center line between Portuguese Timor and Indonesia. At best, it is a simplification, especially since the rivers that serve as the starting points of the lines are east of the border between the Indonesian West Timor and East Timor. The shift of the border to the east has a serious consequence: the entire Laminaria-Corallina gas field lies outside the cooperation zones and, according to the 1972 treaty, in the Australian sea area.

The eastern border of Zones A and B follows a line drawn from the Indonesian island of Leti , east of Timor . The line touches the previous end point of the 1972 boundary in the east and, due to its starting point further east, has an angle that also reduces zone A in the east. Instead of 70% of the Greater Sunrise gas field (also called Greater Sunrise Sunrise Troubadour ), only 20% are in Zone A. Australia claimed the rest for itself. The total reserves of this field, which is considered to be one of the most productive in Asia, are estimated at a value of 40 billion US dollars.

The Zone C boundaries to the west and east are elongated lines connecting the ends of the 1972 border with starting points in Northern Australia. The east line begins at the northernmost point of Melville Island , the western limit at the northernmost point of Long Reef .

Treaties between Australia and East Timor

A guerrilla war raged in East Timor until 1999, when the population voted in favor of an independent state in an independence referendum under UN supervision. With the help of an Australian-led emergency force , East Timor was placed under UN administration until 2002 and finally released into independence. According to the Convention on the Law of the Sea, it was not possible to draw a border along the center line because Australia withdrew from the treaty in March 2002, a few months before East Timor's independence.

The negotiations between Australia and East Timor finally led to the Timor Sea Treaty on May 20, 2002 . The cooperation zones B and C ceased to exist and zone A became the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA), in which the controls on oil production are shared. 90% of the income goes to the state of East Timor, which builds up a fund in order to be able to dispose of funds even after the sources are exhausted. East Timor also uses it to finance development measures for the infrastructure. Overall, the share of revenues from oil and natural gas production in 2013 accounted for more than 95% of the total revenues of East Timor. The status of the sea area between the 1972 border and the center line was not determined by this treaty. This also applied to 80% of the Great Sunrise gas field. The Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) was supposed to remedy this shortcoming after an agreement, the "Sunrise IUA" (Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste relating to the Unitization of the Sunrise and Troubadour Fields) of March 6, 2003, was not ratified and the Australian government insisted on the validity of the old treaties in May 2004. East Timor accused Australia of withholding a million US dollars in license income every day by drawing the border from East Timor . With the CMATS of January 12, 2006 a 50/50 division of the income from the gas field was agreed. The other areas west and east of the JPDA, which would actually belong to the exclusive economic zone of East Timor, were initially left to exploitation by Australia. A 50-year moratorium on the maritime border was agreed without East Timor waiving its claims. Both countries ratified the agreement in 2007.

Dispute with the funding companies

The American group ConocoPhillips is exploiting the Bayu-Undan natural gas field . The gas is sent to Darwin, Australia for further processing. The neighboring state of East Timor will share in the profits. In 2010 there were irregularities in the billing, among other things because ConocoPhillips extracted helium from the gas field and East Timor did not inform about the extraction. East Timor also accused ConocoPhillips of under paying taxes and imposed a heavy fine. ConcocoPhilipps therefore went to court.

The Australian company Woodside Petroleum was commissioned to exploit the Greater Sunrise field . However, there was a dispute between the East Timorese government and Woodside over plans to process the natural gas. Woodside also wanted to route the natural gas to Darwin, while East Timor insists on a pipeline to the south coast of the country. There is already an infrastructure plan for the entire region from Beaco to Betano to Suai in order to be able to offer jobs to the local population. East Timor also refused to process the natural gas offshore. Finally, East Timor temporarily stopped the gas production license.

Espionage scandal and trial

In 2013 it became known that the Australian secret intelligence service ASIS ( Australian Secret Intelligence Service ) had installed bugs in the East Timorese cabinet room and wiretapped conversations concerning the negotiations on the border with Australia. The listening devices had been installed by secret service employees who worked as development workers in East Timor. They had renovated the rooms. East Timor therefore questioned the validity of the moratorium on the border and went to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

On December 3, 2013, a few days before the trial began, the Australian domestic intelligence service ASIO ( Australian Security Intelligence Organization ) raided the offices of Bernard Collaery , a lawyer working for East Timor, in Canberra, and a former ASIS agent who is believed to be a whistleblower in the case. Documents and data carriers were confiscated. The passport was confiscated from the ASIS agent. He actually wanted to appear as a key witness (code name Witness K ) at the Hague trial after he learned that former Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer , who was responsible for espionage , was a paid advisor at Woodside Petroleum after leaving parliament assumed. East Timor's government protested violently, but Australian Justice Minister Michael Keenan and Prime Minister Tony Abbott said the action was in the legitimate interests of “ Australian national security ”. In front of the Australian embassy in Dili on December 5, around 50 people demonstrated against what they believed to be oil theft. A kangaroo carrying a bucket of “Timor oil” became a symbol of protest. It appeared on the demonstration posters as well as on graffiti on the embassy wall. In addition, emus for Australia and crocodiles for East Timor were also found in the drawings . Further demonstrations with a few hundred participants followed in the next few days.

On March 3, 2014, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Australia to stop espionage against East Timor. Communication between East Timor and its legal advisers should not be disturbed. Australia was allowed to keep the seized documents until the end of the negotiations, but was not allowed to evaluate them or use them against East Timor. A few days later, Australia warned East Timor that the dispute over the sea borders could endanger relations between the countries. At the end of the year, the two parties to the dispute agreed on a suspension of the proceedings and new negotiations on the sea borders.

In 2015, Australia agreed to return the documents confiscated from the lawyer to East Timor. It happened on June 3rd. On February 23, 2016 there was another demonstration in front of the Australian embassy in Dili, this time with over 1000 participants.

Witness K and Bernard Collaery are currently on trial in Australia for divulging classified information.

Arbitration and renegotiations

In 2016 the dispute intensified again. The Movimento Kontra Okupasaun Tasi Timor (MKOTT, German movement against the occupation of the Timor Sea ) describes the situation as an "occupation by Australia" and the protest against it as the "second struggle for independence". From March 21 to 24, over 10,000 Timorese demonstrated in front of the Australian embassy in Dili, as well as in other parts of the country. In Adelaide and in front of the Australian embassies in Manila , Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur , exiled Timorese demonstrated together with local activists. The largest demonstration outside of East Timor drew hundreds of protesters in Melbourne . During the week, Facebook called for a public call for the border line to be drawn along the center line between the countries ( #MedianLineNow and #HandsOffTimorOil ). The opposition Australian Labor Party spoke out in favor of renegotiating the border with East Timor.

On April 11, 2016, East Timor called a commission under the Convention on the Law of the Sea to arbitrate the border dispute. It is the first time in history that this instrument has been used. The arbitration commission was supposed to issue a report within a year, but it was not binding. The counterparties should seek a solution themselves on the basis of the report. In any case, the Australian government stated at the first meeting of the arbitration commission on August 29th that it would only consider the final report of the commission as binding if it did not take up the issue of demarcation. Regardless of the arbitration, East Timor continued to seek a judgment by an arbitration tribunal, which is located at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, with the annulment of the CMATS.

The Dane Peter Taksøe-Jensen was appointed President of the Arbitration Commission. East Timor's representatives are the German Rüdiger Wolfrum , judge and former president of the International Tribunal for the Sea, and Abdul Koroma , former judge at the International Court of Justice from Sierra Leone . Australian representatives are Rosalie P. Balkin , former Deputy Secretary-General of the International Maritime Organization , and Donald Malcolm McRae , an expert on oceans and international law from Canada .

Australia initially refused direct negotiations to draw a border, but on September 26, 2016 the Arbitration Commission decided that Australia had to accept it. Australia gave its consent.

In January 2017, the governments of Australia and East Timor announced that the CMATS should be dissolved. On September 2, the basic agreement on the establishment of the boundary was announced and finally on March 6, 2018 in New York the Treaty on the demarcation of the Timor Sea (Treaty between Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste establishing their Maritime Boundaries in the Timor Sea) signed by Ministers Julie Bishop and Ágio Pereira . East Timor's chief negotiator, Xanana Gusmão , received a triumphant welcome on his return to East Timor on March 11th. His car parade was celebrated by a large crowd on the drive from the airport to downtown Dilis.

The maritime border between the two states now runs along the center line. 100% of the income from the Bayu Undan field and the currently closed Kitan field will now go to East Timor. Australia waives claims to this sea area. The more than two billion US dollars that Australia has already earned from the two fields will not be repaid to East Timor. In the east, the maritime border divides the Sunrise Field, whose income is further shared.

Prime Ministers Scott Morrison and Taur Matan Ruak exchange ratified treaties in a ceremony in Dili

Gusmão had caused a stir twelve hours before the contract was signed when he claimed in a press release that Australia was working with the extraction companies against East Timorese interests. The open issue is still the question of whether the natural gas should be liquefied in Darwin or Beco. ConocoPhillips prefers the existing facility in Darwin as a location, which is being advertised intensively. In the so-called Barossa project, the aim is to connect the pipeline coming from the Sunrise field to the old pipeline from the Bayu-Undan field, whose yields are nearing the end. This is to be made palatable to East Timor by receiving 80% of the revenue from the Sunrise field when the further processing of the natural gas takes place in Darwin. If the gas is sent to Beaco, East Timor only receives 70%.

In 2019, the new treaty was ratified by the parliaments of Australia and East Timor.

See also

Documentaries

- Amanda King : Time to Draw the Line (2017).

literature

- Kim McGrath: Crossing the Line: Australia's Secret History in the Timor Sea , 2017.

Web links

Institutions

- Arbitration at the Permanent Court of Arbitration: Arbitration under the Timor Sea Treaty (Timor-Leste v. Australia) (no procedural documents available)

- Proceedings before the International Court of Justice: Questions relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia) (procedural documents available)

- Arbitration at the Permanent Court of Arbitration: Arbitration under the Timor Treaty (Timor-Leste v. Australia) (no procedural documents available)

- Conciliation proceedings at the Permanent Court of Arbitration: Conciliation between The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste and The Commonwealth of Australia (procedural documents partially available)

Documents

- Google maps showing the boundaries in the Timor Sea

- Agreement establishing certain seabed boundaries in the area of the Timor and Arafura seas, supplementary to the Agreement of 18 May 1971 (with chart). Signed at Jakarta on October 9, 1972

- Timor Gap Treaty of 1989

- Water Column Boundary Agreement 1997

- Timor Sea Treaty 2002

- Sunrise IUA 2003

- International Court of Justice: Order: Request for the Indication of Provisional Measures , March 3, 2014

- Treaty between Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste establishing their Maritime Boundaries in the Timor Sea

Further web links

- Government of East Timor: Maritime Boundary Office , official website on the border dispute (English, Portuguese, tetum)

- La'o Hamutuk: Information about Treaties between Australia and Timor-Leste Goodbye CMATS, welcome Maritime Boundaries

- La'o Hamutuk: Timor Sea Justice Campaign

- La'o Hamutuk: South Coast Petroleum Infrastructure Project

- La'o Hamutuk: MKOTT statements to Australia and TL , March 22, 2016

- Colloquium at University of New South Wales: Timor Sea Maritime Boundaries: a presentation for the ICJA / ILA Colloquium at University of New South Wales

- Timor Leste vs. Australia at International Court of Justice on UN web TV

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e La'o Hamutuk: Information about Treaties between Australia and Timor-Leste Goodbye CMATS, welcome Maritime Boundaries , accessed on March 18, 2018.

- ↑ Kim McGrath: Oil, gas and spy games in the Timor Sea , the Monthly, April 2014 , accessed May 1, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e f g The View from LL2: Google Earth Map for the Timor Sea Maritime Boundary Dispute , March 17, 2014

- ↑ The Guardian: Timor-Leste: court upholds Australian government refusal to release documents on Indonesia's invasion , July 3, 2020 , accessed July 4, 2020.

- ^ Government of Timor-Leste: Australia changes position on maritime boundaries , June 5, 2014 , accessed July 1, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d Newmatilda.com: Stop Spying On Timor, Court Tells Australia , March 5, 2014 , accessed March 24, 2014.

- ↑ 12th anniversary of Australia's withdrawal from the International Court of Justice on maritime boundary matters ( Memento of March 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Timor Sea Treaty between the Government of East Timor and the Government of Australia . In: Australasian Legal Information Institute - Australian Treaty Series . 2003. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald: Australia accused of playing dirty in battle with East Timor over oil and gas reserves , December 28, 2013 , accessed March 24, 2014.

- ^ Jesuit Social Justice Center: Closing the Timor Gap Fairly and in a Timely Manner ( Memento of April 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) September 3, 2004.

- ↑ La'o Hamutuk Bulletin Vol. 7, No. April 1, 2006 - The CMATS Treaty

- ↑ a b ABC Australia: Taxing Times in Timor , accessed December 30, 2013.

- ↑ a b c Neue Zürcher Zeitung: Australian bugs in Dili , December 7, 2013 , accessed on December 16, 2013.

- ↑ The Age: ASIO raids: Australia accuses East Timor of 'frankly, offensive' remarks , January 21, 2014 , accessed March 24, 2014.

- ↑ Australian Financial Review: East Timor PM: raid 'unacceptable' , December 4, 2013 , accessed December 16, 2013.

- ↑ ABCnews: East Timor spying case: PM Xanana Gusmao calls for Australia to explain itself over ASIO raids , December 5, 2013 , accessed December 16, 2013.

- ↑ East Timor’s Government website: Statement by His Excellency the Prime Minister, Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão , December 4, 2013 , accessed December 16, 2013.

- ↑ Netzpolitik.org: Industrial espionage: Australian intelligence services fight over billions in gas field , December 4, 2013 , accessed on December 16, 2013.

- ↑ Tempo Semanal: Protests in Dili: "Aussie Government are Thieves & Alleged AUSAID involved in spying on East Timor" , December 8, 2013 ( memento of March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Australia Network News: East Timor denies violent protests outside Australian embassy, amid spying row , December 7, 2013 , accessed March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald: Vandals target Australia with graffiti on walls of East Timor Embassy , February 13, 2014 , accessed March 26, 2014.

- ↑ ABCnews: Australia issues diplomatic warning to East Timor saying maritime boundaries case risks relationship , March 17, 2014 , accessed March 24, 2014.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald: Australia and East Timor restart talks on maritime boundary , October 28, 2014 , accessed October 28, 2014.

- ↑ Tom Allard: George Brandis hands over to East Timor docs seized by ASIO , Sydney Morning Herald, May 3, 2015 , accessed May 9, 2015.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald: Protesters in Dili want Australia to settle oil dispute with East Timor , February 23, 2016 , accessed February 23, 2016.

- ↑ The Guardian: José Ramos-Horta urges Australia to drop Witness K case , July 30, 2018 , accessed August 6, 2019.

- ↑ Channel News Asia: Maritime border dispute with Australia a 'second fight for independence' for Timor-Leste , accessed on March 22, 2016.

- ↑ BBC: Thousands rally in East Timor over Australia oil dispute , accessed March 23, 2016.

- ↑ SBS: East Timor determined to get Australia's attention over 'unfair' sea boundaries , March 24, 2016 , accessed March 24, 2016.

- ↑ SAPO Notícias: Milhares protestam em Dilí contra Austrália por causa de fronteiras marítimas , May 22, 2016 , accessed on March 22, 2016.

- ^ The Age: Labor offers new maritime boundary deal for East Timor , February 10, 2016 , accessed March 27, 2016.

- ↑ a b Patrick Zoll: Öl, Gas und Espionage , NZZ, August 30, 2016 , accessed on August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Australian Foreign Office: Conciliation between Australia and Timor-Leste , August 29, 2016 , accessed August 30, 2016.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald: East Timor takes Australia to UN over sea border , April 11, 2016 , accessed April 11, 2016.

- ↑ Press release by the government spokesman for East Timor: Timor-Leste Launches United Nations Compulsory Conciliation Proceedings on Maritime Boundaries with Australia , April 11, 2016 , accessed on April 11, 2016.

- ↑ Sapo24: Nomeado presidente da comissão de conciliação de fronteiras Timor-Leste-Austrália , June 29, 2016 , accessed on June 30, 2016.

- ↑ SBS: Australia loses bid to reject compulsory conciliation with Timor Leste , September 27, 2016 , accessed August 27, 2017.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald Australia's unscrupulous pursuit of East Timor's oil needs to stop , January 11, 2017 , accessed January 20, 2017.

- ↑ Michael Leach Bridging the Gap , September 4, 2017 , accessed September 4, 2017.

- ^ Western Advocate: Hero's welcome for Timor border negotiator , March 12, 2018 , accessed March 18, 2018.

- ↑ Voice of America: Australia Ratifies Maritime Boundaries with East Timor , July 29, 2019 , accessed July 30, 2019.