History of the Ivory Coast

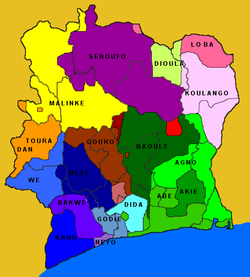

The history of Ivory Coast is the history of the modern West African state of Ivory Coast ( French: Côte d'Ivoire ), the French colony of the same name from which this state emerged, as well as the history of the peoples and empires that lived or lived on the territory of the present state. still live today. The state of Ivory Coast is the result of colonial demarcations in which no consideration was given to previously existing geographical or natural areas, or to religious, linguistic or cultural boundaries or units. The national territory therefore unites regions that did not have a common history before this border was drawn. Other peoples, in turn, are separated by the state border from regions outside the present-day state, with which they share a common history.

History of the peoples and empires of the Ivory Coast prior to colonization

Little is known about the early inhabitants of the Ivory Coast area; they were probably displaced or assimilated by the ancestors of today's inhabitants. The northern part of today's Ivory Coast was shaped by the influence of the great Sahel empires in the centuries before colonization . Since the 11th century, Islam spread through these trade contacts and armed conflicts in the northern parts of the country. The north-western corner of the Ivory Coast was part of the great empire of Mali until the 14th century and the entire northern region was involved in trade with these empires ( Songhai , Empire of Ghana, etc.) for centuries . Mounted armies from the north repeatedly conquered large parts of the country. Long before the Europeans arrived on the coasts, there were important trading cities here, such as Bondoukou or Kong, which had gradually developed into larger or smaller, Islamic city - states .

In the 17th century, Seku Wattara , a leader of an equestrian army who came from the north, conquered the city-state of Kong and set himself up as ruler. Under him and his successors, Kong became the most powerful state in the region. In 1725 a cavalry army from Kong even reached Niger and attacked the city of Segu . Kong was a center of Islamic learning, the destruction of which in 1895 by the Muslim military leader Samory Touré would later trigger outrage in the Islamic world of West Africa .

The Kingdom of Abron was the first of several empires within the Ivory Coast to be founded in the 17th century by a people from the Akan group who had emigrated to the Ivory Coast due to conflicts with or within the Ashanti kingdom . The Abron were originally part of the Akwamu Empire in the southern part of what is now Ghana . From there they migrated to the area of the city of Kumasi, where they were expelled by the Ashanti in the 17th century . Then they founded their empire in the Ivory Coast, which soon ruled the important trading city of Bondoukou. A good hundred years later they became vassals of the Ashanti Empire.

In the middle of the 18th century, the southeast and central Ivory Coast again became an immigration area for Akan peoples from the Ashanti Empire. There, after the death of the ruler (" Asantehene ") Opoku Ware I in 1750 , internal disputes broke out and a larger group left their homeland for the west and south, to today's Ivory Coast. From these groups emerged today's peoples of the Baoulé and Agni , who gradually ousted the native Senufo and Guru . Some of these emigrants were led by Awura Poku , a brave woman who built her capital near what is now the city of Bouaké . After her death in 1760, her niece Akwa Boni took over the management of the Baoulé. Under their rule they conquered the gold-rich areas in the Bandama region. After Akwa Boni's death, the unity of the Baoulé broke up, although they still ruled large parts of southern Ivory Coast when the French arrived.

Early contacts with the Europeans and colonial conquest

Since the end of the 15th century there have been trade contacts between Europeans and the coastal peoples of the Ivory Coast. The first Europeans on this coast were the Portuguese , who ruled the trade for over 100 years. Ivorian city names such as Sassandra , San Pedro or Fresco still remind of this today. In contrast to the gold coast adjoining to the east , the European powers did not set up any fortified bases here for a long time. It was not until 1698 that the French built a wooden fort near Assinie , in the easternmost part of the country's coast, and named it St. Louis , but gave it up again in 1704. In the middle of the 19th century, the French made their first permanent contacts with the coastal peoples through traders and missionaries. The name Côte d'Ivoire, "Ivory Coast", was demonstrably used by the French admiral Louis Edouard Bouet-Willaumez in 1839. In 1843/44 Bouet-Williaumez concluded treaties with rulers from the areas around the coastal towns of Grand-Bassam and Assinie, which made these areas French protectorates . From here, French officers and NCOs later began the colonial conquest of the Ivory Coast with the help of African mercenaries. France's colonial efforts flagged from 1871 due to the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War , but were rekindled by the agreements of the Congo Conference of 1885 on the coasts of Africa and especially the similar treaties of 1890 on the interior of the continent.

These agreements between the European colonial powers provided that only that country would be accepted as part of the European colonial area that was actually ruled by a European power - “taking possession” through a ceremony was no longer sufficient. The conference fueled the so-called "Scramble for Africa" ( race for Africa ). In 1893 the Ivory Coast was declared a French colony . The first governor of the new colony was Lieutenant Louis-Gustave Binger , who had been delegated from Dakar to negotiate "treaties of protection" or the conquest of the Empire of Kong, which around 1890 covered large parts of the northern Ivory Coast and adjacent areas deep into what is now Burkina Faso dominated into it. Grand-Bassam became the first capital of the colony. Binger negotiated the borders of the French Ivory Coast with the neighboring British colony of Gold Coast and the independent Liberia to the west, as well as a "protection treaty" with the Empire of Kong. The French rule was soon opposed both in the extreme north, by the Islamic leader (" Almamy ") Samory Touré , and in the coastal regions. From 1891 to 1918 different parts of the country were permanently in open war with France or in revolt.

The resistance Samory Tourés

The toughest resistance came from Samory Touré , who had conquered the Empire of Kong in 1895 and destroyed the city. Samory Touré was a military leader and Islamic reformer whose first state was founded several hundred kilometers to the west, on the borders of the French colonies of Guinea and Senegal . The French drove him out of this empire in bloody battles in the early 1890s. He established his second empire in the area of Kong. In 1896 the British conquered the neighboring Ashanti Empire and were Samory's direct neighbors in the east. Samory's attempts to ally with the British against the French failed. In 1898, French troops advanced simultaneously on Samory's empire from the west, south and north, while the British blocked his retreat to the east. The French promised him safe conduct to his hometown, where he would live undisturbed. Samory accepted the offer and surrendered. The northern Ivory Coast was finally French. However, the winners immediately broke their promise and deported Samory Touré to their colony in Gabon , where he died in 1900.

The Baoule and Agni struggle for independence from 1891 to 1917

The struggle for independence of the peoples on the coast and in the center of the colony was led by the Akan peoples of the Baoule and Agni mentioned above, who had immigrated from the Ashanti area 150 years earlier. The wave of uprisings began when the French broke the "protection treaties" negotiated with these peoples from 1878 to 1889 in several places by interfering in the choice of traditional heads and demanding the provision of men as porters and forced laborers. When the construction of a railway line began in 1893, they increasingly asked for forced labor and expropriated African land for the route.

In 1900 they also tried to enforce a poll tax for the residents of the colony. The uprising that began in 1891 was not centrally cited, as the Baoule were not united in a centralized kingdom (although several smaller chiefdoms cooperated in this) and had the character of a guerrilla war that lasted for years . In 1908 the French only actually had a narrow stretch of coast under control. That year the colonial power sent a new governor to the Ivory Coast. Governor Gabriel Angoulvant sought the solution in brutal military repression of the local population. He had hundreds of villages destroyed and the residents relocated to larger places that were easier to guard. 220 African leaders were deported and the system of forced labor expanded considerably. The campaign was successful and in 1915 French military control was restored. In 1916 there was the last major uprising of the Baoule and Agni, which at times threatened French rule in a similar way to that in 1908. The uprising finally ended with the extensive emigration of the Agni group to the neighboring British Gold Coast and thus under a more tolerable form of colonial rule .

Establishment of the French colonial power from 1918 to 1944

In 1904 the colony became part of French West Africa . After Grand-Bassam , Bingerville became the capital, and from 1933 Abidjan . The upper class of the northern areas, especially the Dyula traders, were soon ready to cooperate with the colonial power, as they gave them lucrative access to the coastal cities. The French also recruited most of the workforce from the north for their economic ventures in the forest areas of the center, for logging and plantation construction ( rubber , palm oil , palm nuts , and increasingly cocoa and coffee since the 1930s ). This emigration of workers had a negative effect on the economic development of the north. In some cases, workers were also recruited from the neighboring colonies such as Upper Volta , and some of the immigration from these areas was voluntary.

In the areas that until then had no major state units, the French used "traditional chiefs" at their discretion, but these were hardly accepted by the population. The upper class of the rebellious Baoulé increasingly benefited from the colonial structures in the period between the wars. Traditionally, the "chiefs" had exercised some control over the usable land and labor of the population for the general benefit of society. Under colonial conditions, they were able to use this influence for their selfish interests and many became successful planters.

With the economic success, the anti-colonial resistance soon subsided in the lower social classes. After 1918, the colonial administration could afford to set up “advisory assemblies” at the district or city level. Support associations ( amicales ) were founded in the cities, but they were not allowed to engage in trade union or political activities. The policy of assimilation , the "transformation" of western educated locals into "African French" was partially successful here.

The Catholic Church covered the country with a network of elementary schools and there were several secondary schools for affluent and ambitious locals. The success of the Catholic Church was also related to the success of a Christian preacher from Liberia, William Wadé Harris , who in 1914 alone converted 120,000 people in Ivory Coast to his Christianity (mixed with traditional elements). Never before or since has there been a comparable Christian mass movement in West Africa. Harris benefited from the decline of the Ivory Coast's political and religious authorities, while accelerating them significantly. A small number of locals also received French citizenship up to 1930 , the other inhabitants of the country were not considered "citizens" but rather "subjects" ( sujets ) of France.

The "subjects" were under the rule of the " Code de l'indigénat " ("Native Laws"), a catalog of laws and regulations which, for example, required every male, adult native to 10 days of unpaid forced labor per year, but they did not have any political obligations Rights granted. The situation worsened when in 1940 parts of the French "motherland" were occupied by German troops and the Vichy regime took power in the unoccupied part of France.

France's colonies had to choose between the Vichy regime , which was collaborating with the Germans, and Charles de Gaulle's government-in-exile in London , ie " Free France ". The colonial rulers of French West Africa - and thus the Ivory Coast - decided in contrast to French Equatorial Africa for Vichy France. The Vichy supporters in French West Africa promoted forced labor and introduced elements of racial segregation for the first time in accordance with the racist laws of Nazi Germany . "Whites-only" signs appeared in hotels and cafes, and African customers were served separately in stores. The forced laborers were only assigned to the French entrepreneurs and the white settlers, the "colons", received twice the price for their cocoa as the local growers, which reduced the cocoa production by the locals to a fraction. In protest against these measures, a chief and 10,000 of his subjects left the colony in 1941 and emigrated to the British Gold Coast, where he offered his services to the representatives of "Free France". The defeat of Germany and thus Vichy France also meant a defeat of this racist line of French colonial policy. For the Ivory Coast it ended in 1943 with the surrender of the Vichy-loyal colonial administration of French West Africa to the Allies and "Free France".

1944 to 1960: The decision between independence and attachment to France

1944 to 1948: reforms and establishment of the RDA

The victory of Free France brought about a turning point for the entire French colonial policy . At the conference in Brazzaville (the capital of French Equatorial Africa and at that time also the capital of "Free France") in January 1944, high-ranking representatives of the French colonies in Africa recognized, at the instigation of General de Gaulle, the right of the colonies to be represented in the French constitutional assembly to draft a constitution for post-war France. The conference recommended, among other things, greater autonomy for the colonies, parliamentary representation of the white settlers and the natives, the right of workers to organize themselves, and the abolition of the “Code de l'indigénat” and forced labor.

In the Ivory Coast the " Syndicat Agricole Africain " was founded, an association of local planters who opposed the preference for the "colons". Founding member was the wealthy planter and later president of the independent Ivory Coast, Félix Houphouët-Boigny , who was to determine the country's politics for the next 40 years. In 1945, Houphouët-Boigny was elected as the representative of the locals in the Constituent Assembly in Paris in the first national election. However, this election was not general, but carried out by a limited circle of voters. The white settlers were also allowed to send a representative to the assembly.

In 1946, forced labor was finally abolished, a success that many people in Ivory Coast associated with the name Houphouët-Boignys. In 1946 the Parti Democratique de la Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI, Democratic Party of the Ivory Coast ) was founded with Félix Houphouët-Boigny at its head. At the end of the same year, this party merged with parties from several other areas of French Africa to form the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA), which in turn was headed by Félix Houphouët-Boigny. The aim of this association was not the independence of the French colonies in Africa, but their equal integration into the " Union française " under the leadership of France.

Félix Houphouët-Boigny had already assured in his first election manifesto: "I love France, to which I owe everything ... There is not a single good will who can prove to me that I have shown a lack of loyalty to France." Although a staunch representative of free enterprise, Félix Houphouët-Boigny's party between 1946 and 1950 an alliance of convenience with the French Communist Party , which was part of the French government until 1947 and provided the governor of the Ivory Coast. During this time, Boigny's RDA supported the strikes of the railroad workers and market women in 1947.

1949 to 1951: relapse into repression

In 1948, the communist governor Georges Orselli had to vacate his post. His successor Laurent Péchoux had instructions to take action against Houphouët-Boigny's RDA. In the whole of French Africa the colonial rulers became more repressive during this phase, but in the Ivory Coast the governor Pechoux unfolded a terror that was reminiscent of the suppression of the uprisings between 1891 and 1919. He was particularly supported by the French settlers, who saw themselves threatened by the new self-confidence of the "natives" and had already lost a number of privileges. The saying of a settler became known: "The matter will probably not be settled without 10,000 dead" ( La situation ne peut s'arranger ici qu'avec 10,000 morts ).

The repression of the colonial government against all supporters of the RDA resulted in 52 dead and hundreds injured within one year, from February 1949 to February 1950. Pro-Boigny villages were subject to extra taxes and hundreds of traditional “chiefs” were deposed. RDA gatherings were banned. The Ivory Coast Catholic Church refused to allow victims of repression to have a Christian burial. In some areas, the pre-World War I "Harris Movement" revived. When Houphouët-Boigny was about to be thrown in prison, there were mass demonstrations and boycotts of European companies. Houphouët-Boigny received support not only in the Christian-animist south, but also in the predominantly Islamic north, especially in the regions that were allied with Samory Touré 70 years earlier.

In 1950, Félix Houphouët-Boigny left the country for Paris because he feared for his life. The advantage of being tied to the Communist Party had turned into its opposite. In the same year he broke ties with the Communist Party and formed an alliance with the Union démocratique et socialiste de la Résistance , the party of the future French President François Mitterrand .

1951 to 1958: Cooperation between the RDA and the colonial regime, economic boom

Félix Houphouët-Boigny and his RDA were back in the camp of the rulers. Pechoux had to leave the Ivory Coast in 1950 and was transferred to Togo , France , where he used similar methods against the separatist tendencies of the Ewe . Houphouët-Boigny and the colonial administration changed their policy by 180 degrees and began a strong cooperation. Most of Houphouët-Boigny's political followers, who had been imprisoned in previous years, were pardoned. The RDA split in 1950, its "moderate" wing was led by Houphouët-Boigny and the colonial administration began to support the RDA as openly as it had fought it before.

Until 1957, Houphouët-Boigny was a member of several French governments and President of French West Africa. His collaboration with the colonial rulers went so far that he even justified the brutal colonial war of the French in Algeria . At the same time, the Ivory Coast experienced an enormous economic boom, based on the export products cocoa and coffee. In 1956 the electoral legislation was reformed and the Ivory Coast was given extensive internal autonomy . The women's suffrage was also introduced 1956th In 1958 the Ivory Coast's own constitution came into force and in 1959 Houphouët-Boigny successfully campaigned for the dissolution of French West Africa. In doing so, he opposed the majority of the other African leaders who feared a " Balkanization " of West Africa.

For Houphouët-Boigny, on the other hand, the decisive factor was that in this way the Ivory Coast did not have to share the wealth it had made with the poorer parts of French West Africa. The Ivory Coast budget increased by 152% with autonomy. When Charles de Gaulle asked the French colonies in 1958 to decide whether to remain in the French Union or to obtain immediate independence, the Ivory Coast clearly voted to remain with France.

1959 to 1960: The step towards independence

Until 1959, Houphouët-Boigny was a clear opponent of the separation of the country from France. Charles de Gaulle himself, however, suggested independence to the French colonies while maintaining a loose link with France. Only then did Houphouët-Boigny and the leaders of the remaining republics of French West Africa "demand" independence. Shortly afterwards, relevant documents were signed with France and independence was declared on August 7, 1960 under the name of the Republic of "Côte d´Ivoire" ( Ivory Coast ).

The independent Republic of Côte d'Ivoire 1960 to 2002

1960 to 1978: Consolidation of power and "Ivorian economic miracle"

98.7% of the electorate cast Felix Houphouët-Boigny in November 1960, who was thus directly elected as the first President of the independent republic. He held this office until his death in 1993. Abidjan became the capital of the Ivory Coast. The Ivory Coast constitution, based on separation of powers and other democratic principles, was de facto repealed in the first years of independence. A majority vote , which was not applied to individual constituencies but to the country as a whole, meant that the majority party (Houphouëts PDCI) received all the seats in parliament. Houphouët-Boigny was not only president of the state, but also of the PDCI.

As President of the Republic, he personally appointed the heads of all regional organizations in the country: the 6 departments, 24 prefectures and even the 107 sub-prefectures. He also appointed the members of the National Assembly. Within the party, Houphouët-Boigny got rid of the young academics, but also the members of certain regions. In 1962 and 1963, conspiracies against the government were uncovered which led to " purges " at the highest levels in the party and state. He protected himself against the danger of a military coup by founding a party militia with several thousand men and building an army whose leadership consisted of French born in the country.

Nevertheless, Felix Houphouët-Boigny's rule was not primarily based on violence, but on a policy of "balanced" allocation of posts and privileges to the country's upper class and the general satisfaction of broad sections of the population due to the general economic development, the "Ivorian economic miracle" .

The economic starting position of the country was already significantly better than in the other countries of the former French West Africa when it gained independence. Houphouët-Boigny refrained from any form of economic experimentation in order to reduce the dependence on French capital and know-how and also to replace the established French specialists with local people. The country attracted significant investment from the old "motherland". At the end of the 1970s, Ivory Coast was the largest cocoa producer and the third largest coffee producer in the world, as well as a major exporter of palm oil , cotton and coconuts . In the 1970s the state invested in industry and in 1980 the country had a food, textile and fertilizer industry that was important by African standards.

The downsides of this development model were considerable development differences between the booming cities and the impoverished rural areas, especially in the north. The resulting rural exodus caused unemployment to rise in the cities as well. Unemployment protests in Abidjan in September 1969 led to the massive arrest of demonstrators who, among other things, had called for a broader “Ivorization” of jobs, ie the replacement of French experts in business and administration by locals. Another area of conflict arose between the locals and the hundreds of thousands of unqualified immigrants, especially from Upper Volta (today Burkina Faso ). This labor migration was deliberately promoted by the government in order to provide cheap labor for the large farms.

In the 1970s, Houphouët-Boigny rejuvenated the political apparatus and began to address dissatisfaction in the country through public “dialogues” in which, for example, in 1974 he discussed with 2,000 party workers. However, these "dialogues" did not result in substantial reforms. Instead, he promoted the cult around himself through extensive tours of the country and by publicly accusing leading politicians of corruption.

1978 to 1993: economic crisis and tentative reforms, end of the Felix Houphouët-Boigny era

In the late 1970s, prices for cocoa and coffee, the Ivory Coast's two main exports, plummeted. The decline in prices continued into the 1980s. Up until then, coffee and cocoa had also been the main sources of income for the Ivorian state, which - also due to various bad investments in previous years - now had to spend a considerable part of its (drastically reduced) income on debt servicing. The general living conditions of the population deteriorated and unemployment increased.

Necessary reforms were nevertheless not carried out, even when international bodies urged them - the Ivorian elites were not interested in reforms. Politicians were betting that the global economy would revive and revenues would rise. In 1982/83 there were threatening demonstrations by students and university teachers. The president mastered this crisis with bogus democratic measures such as a television speech lasting several hours and a certain concession with the demands for "Ivorization" in order to take away the students' fear of unemployment. In 1983, however, Houphouët-Boigny declared the small town of Yamoussoukro , his hometown, the capital of the country and had the largest basilica in the world built there for 200, according to other estimates even 400 million US $ - from his private assets, as he assured him.

In 1990 the state was practically bankrupt and had to stop its debt payments to the World Bank and the IMF and save drastically on expenses - i.e. salaries for employees and support services for students. There were again demonstrations and calls for Houphouët-Boigny's resignation and real democracy. The government responded unsuccessfully with arrests and school closings and finally had to withdraw austerity measures in April and allow new parties to be admitted. In October of the same year, Houphouët-Boigny won a presidential election one last time. His opponent was Laurent Gbagbo from the Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI).

Due to the debt crisis, the Ivory Coast was forced to bow to the dictates of the World Bank, i.e. to carry out so-called structural adjustment measures - privatizations, price increases for previously subsidized basic necessities and other things. The opposition leader Laurent Gbagbo was again at the forefront of the protest movement that rose up in 1992 and was then arrested.

In 1993 the Felix Houphouët-Boigny era came to an end with his death.

1993 to 1999: Bédié presidency and economic recovery

Houphouët-Boigny was succeeded by his deputy, Henri Konan Bédié , on December 7, 1993 . The beginning of his reign was favored by a marked recovery in coffee and cocoa prices, which led directly to a general recovery in the Ivorian economy.

Bédié secured his power by founding so-called “support committees”, which were not part of the governing party's structures, and did not act democratically against unwelcome journalists or insubordinate judges. Allegedly he even planned to imitate his predecessor by building a basilica in his home village. He got rid of his possible rival for the presidency, Alassane Ouattara , a former confidante of Houphouët-Boignys, through an electoral reform that excluded all persons from the presidency whose parents were not both Ivorian citizens. As a result, almost all opposition candidates boycotted the 1995 election and Bédié won the presidency with 96.44% of all votes.

The ideology of Ivorité, which divides the inhabitants of the Ivory Coast into real Ivorians and those ethnic groups from the north of the country, who are identical to the population groups from Mali and Burkina Faso, also dates from the Bédié period . This ideology was developed primarily to marginalize competitors like Ouattara and to take advantage of local conflicts between locals and foreigners .

Economically, he continued the course of structural adjustment measures. While the general economic data developed satisfactorily, the living conditions of the population deteriorated. At the same time, allegations of corruption against his government increased. In 1998 he implemented a constitutional reform that enabled him to extend his presidency from five to seven years.

1999 to 2000: Interlude General Guéï

At Christmas 1999 the Ivory Coast experienced the first successful military coup in its history and Bédié was flown to Togo by the French army. The putschists installed General Robert Guéï as the leader of the military government. The general had already opposed Bédié in the mid-1990s when he refused to mobilize his troops in connection with a political dispute between Bédié and the opposition leader Alassane Ouattara . The coup was followed by the country's economic decline, serious human rights violations and a decline in discipline in the armed forces.

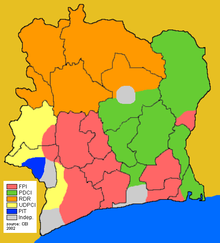

In October 2000 Guéï allowed restricted free elections . When he had to realize that his rival candidate Laurent Gbagbo and his Front Populaire Ivoirien had emerged as the winner of the elections, he refused to recognize the result. Gbagbo had already called on his supporters to protest before the election if there was election manipulation. So after the election there was a general wave of protests in which the FPI supporters prevailed with the help of the gendarmerie sympathizing with the FPI . Guéï was forced to resign and flee. As a result, however, there were further clashes between supporters of the FPI and the RDR, whose candidate Ouattara had already been excluded by the Concept d'Ivoirité before the elections . Numerous casualties were the result of these clashes, with most of the victims among the RDR supporters. Most of these Ivorian Muslims, who come from the north, fell victim to pogroms by the gendarmerie, although the FPI were also indirectly accused of the massacres.

On October 26, 2000, Laurent Gbagbo became President of the Ivory Coast. He was confronted with an attempted coup in January 2001, which he was able to avert only with great difficulty. However, he tried to achieve national reconciliation, for example within the framework of the Forum de la Reconciliation Nationale . Local elections were held, which were fair when possible, and a government was formed in August 2002 that included the opposition parties RDR and PDCI.

Numerous supporters of ex-President Guéï have found refuge in Burkina Faso.

Since 2002: The divided country

Attempted coup in 2002

On the night of September 19, 2002 , part of the army rose against the government: Several important barracks in Abidjan, Korhogo and Bouaké as well as private ministers' homes were attacked, and Interior Minister Boga Doudou shot. The coup failed in Abidjan, where loyal troops prevailed. However, the insurgents gradually brought the northern half of the state and the second largest city in the country, Bouaké, under their control.

Since the uprising took place during a visit by President Laurent Gbagbo to Italy, and because the insurgents were well organized and armed, it soon became clear that it was a coup. The neighboring country of Burkina Faso was suspected of being involved in the coup because many of the insurgent officers had found temporary protection there.

This development also has its background in ethnic tensions. Many immigrants from neighboring countries live in the Ivory Coast, who make up more than a quarter of the total population.

The northern part of Ivory Coast, now detached from the government-loyal south, is divided among 3 rebel groups under the MPIGO and MPCI in the north and the MJP in the west near the border with Liberia .

France, which is pursuing important economic and political goals in the Ivory Coast, worked out a peace plan that was negotiated in Linas - Marcoussis in January 2003 and implemented in the Kléber Agreement . These agreements provided for the formation of a "government of national reconciliation" in which the rebels would hold the Ministry of Interior and Defense. However, this peace agreement was not feasible, which led to new negotiations and the Accra Agreement . As a result of these treaties, Prime Minister Seydou Diarra was able to form a government, but peace could not be ensured. The division of the country was cemented with these agreements and France as a mediator was implausible: The negotiations with the rebels in Marcoussis and, above all, the far-reaching concessions had given the Ivory Coast the impression that the former colonial power had sided with the Forces Nouvelles . This gave a boost to latent anti-French sentiments in the south of the country and directly endangered French interests there.

In July 2003, the civil war was declared over at a ceremony in the presidential palace. On March 26, 2004, the opposition declared its withdrawal from the government of national unity after bloody clashes the day before. A disarmament planned as part of the peace process did not materialize.

On behalf of the UN , more than 6300 blue helmet soldiers were stationed in the country to separate the rebels in the north and the southern part of the country. There are also around 4,500 French soldiers in the country. The latter also act on behalf of the UN, but were stationed in Côte d'Ivoire before the crisis. France has its largest African base in this country.

Escalation in 2004

At the beginning of November 2004 the situation escalated again. On November 4th, government forces unilaterally violated the ceasefire and began air strikes on targets in the north of the country. At the same time, offices of opposition parties and independent newspapers were vandalized in Abidjan. On the third day of the air strikes, nine French soldiers were killed when two Sukhoi Su-25 bombed the rebel-held city of Bouaké and a French camp located there. In response, the French armed forces destroyed the entire air force (two combat aircraft, five attack helicopters) of Côte d'Ivoire within one day on November 5. The presidential palace in Yamoussoukro was also targeted, fueling rumors that France would forcibly remove President Gbagbo from office. Violent anti-French protests broke out in Abidjan, killing dozens of people and injuring over a thousand, including reports of the use of French attack helicopters. Franco-Ivorian relations also hit rock bottom after French intervention undermined President Gbagbo's efforts to militarily defeat the rebels.

In mid-November 2004 France already had 5,200 soldiers in the country, who were reinforced again. At this point around 1,600 French civilians (some with two citizenships) had already been evacuated. They reported dozens of looting and rape by an unleashed mob . There were no fatalities among the French, but the evacuation is interpreted by some observers as the end of French influence in Africa.

Gbagbo's ambiguous role

The rebels in the north remained silent, but the peace plan was still in a serious crisis. According to him, the disarmament of the northern troops should already be under way. In fact, it wasn't. Ultimately, this was probably the source of the new escalation. The southern part of the country under Gbagbo, on the other hand, is accused of actually not wanting the power-sharing. Gbagbo has long been destabilizing the situation with calls for hatred and violence on TV and radio, among other things. By November 15, around 6,000 foreigners had been evacuated via airlift.

At the instigation of France, the Ivorian government was condemned for breaking the armistice at a special AU summit and by UN resolution 1572. On November 15, 2004, the United Nations Security Council imposed an arms embargo on Côte d'Ivoire. Both the southern and northern parts of the country are affected. In addition, a travel ban was imposed on the members of the respective tours in both parts of the country and their foreign accounts were frozen. The arms embargo came into force on the same day, the other measures only on December 15, and only if the ceasefire had not been fully restored by then. All measures were initially limited to 13 months.

After the apparent failure of the French mediation mission , the South African President Thabo Mbeki joined the peace efforts. As a result of his persistence, the conflicting parties announced the official end of the civil war in Pretoria on April 6, 2005, and on July 29, 2005 they agreed on a disarmament agreement. This should pave the way for presidential elections on October 30, 2005, in which all known candidates should be able to participate.

However, the election date soon proved to be unsustainable, especially because of disputes over the electoral roll-out and the seats on the electoral commission. Likewise, the dissolution of the militias stalled because of the same problems. In September 2005, the rebels finally asked Gbagbo to resign and to allow the elections to take place without him, because they see him as the real obstacle to peace. However, the South African side certified that Gbagbo worked well together. In the end, the rebels also declared their distrust in the South African mediation mission, which led to the mediation mandate being officially returned to the United Nations.

However, neither the disarmament nor elections were implemented. The UN decided to extend Gbagbo's term of office (which would have ended in October 2005) by one year, but provided him with a non-party member, Charles Konan Banny , as Prime Minister, who was to prepare elections until October 2006. In mid-January 2006 the situation escalated again. There were violent demonstrations in several places, and clashes between supporters of Gbagbo and UN units in Guiglo left several dead and injured. The UN soldiers stationed there then withdrew to the demilitarized zone a few kilometers to the north. Tear gas and warning shots were used during demonstrations in the capital. The streets of Abidjan are controlled by - mostly young - supporters of Gbagbo, including by means of roadblocks.

Sluggish election preparations

Following a relevant UN decision in early February 2006, accounts of three opponents of the peace process were frozen. The sanctions are directed against Ble Goude and Eugene Djue, who are seen as leaders of militant youth groups and supporters of President Laurent Gbagbo, and against rebel leader Fofie Kouakou. The approximately 7,000 blue helmets stationed in the country were reinforced by around 200 men around the same time. There are also 4,000 French peacekeeping soldiers in the country. The Audiences foraines -called registration of previously undocumented citizens with regard to the agreed election comes only slowly forward. The opposition claims they are being thwarted and partially prevented by members of the ruling party.

At the end of October 2006, President Gbagbo's extended mandate granted by the UN Security Council expired. Therefore, elections should have taken place across the country beforehand. This did not happen because the president refused to update the electoral roll. The north is still ruled by the Forces Nouvelles and the south theoretically by the Banny government. De facto, however, President Gbagbo has long since established parallel structures in the south, into which in particular the income from cocoa cultivation and the still young oil income flow.

Treaty of Ouagadougou

Finally, on March 4, 2007, after lengthy negotiations between President Gbagbo, rebel leader Soro and Burkinabe President Blaise Compaoré , a new peace treaty was signed. In contrast to the previous agreements, this agreement provides for a permanent framework for consultation in which, in addition to Gbagbo, Soro and Compaore, Bédié and Ouattara are also represented. Soro was appointed Prime Minister of the newly formed government. The Ouagadougou Treaty contains detailed agreements on the issuing of identity papers, the electoral roll and the creation of a national army.

A few weeks later, the dismantling of the buffer zone began and there were the first joint patrols of soldiers and rebels. In July 2007, President Gbagbo visited the rebel-held north for the first time in five years. There he took part in an official peace ceremony at which weapons were burned in the presence of numerous African heads of state.

In preparation for the election, 480,000 new birth certificates were issued.

Elections were due to take place on November 30, 2008 after President Gbagbo's mandate had expired in 2005 , but Laurent Gbagbo, Guillaume Soro and other political leaders announced the vote in a joint statement on November 10 shortly before the scheduled date was not to be organized by the end of the month. Reasons include problems with voter registration.

2010 presidential election and dispute over the result

The presidential elections, which were finally held on October 31, 2010 and November 28, 2010, did not lead to the hoped-for unification of the country and the clarification of the balance of power. Incumbent Laurent Gbagbo won the first round of elections with 38% of the vote ahead of his main challenger, Alassane Ouattara , who was considered the "candidate of the north" and received 32%. In the subsequent runoff election, however, Ouattara was able to unite the majority of votes with the support of the supporters of Henri Konan Bédié, who was third in the first round, according to the election commission. The government-loyal Constitutional Council, however, declared the provisional result of the electoral commission to be invalid because the result had not been announced on time. The Constitutional Council also announced a review of election complaints after Gbagbo's party sought to cancel the election results in three constituencies in the north.

The UN , the European Union and others recognized Ouattara as the election winner and president of Ivory Coast.

Government crisis 2010/2011

Laurent Gbagbo was sworn in for another term on December 4, 2010, citing the Constitutional Council. A few hours later, Alassane Ouattara also took the oath of office as president. Forces Nouvelles de Côte d'Ivoire (FN) troops , which had been sent to the south before the election, returned to the north. The division of the country was cemented again. As a result, there were riots and fighting between the former gbagbo-loyal armed forces (FDS) and the FN. In Abidjan, Ouattara supporters , known as Invisible Commands , fought against the FDS. At the end of March, the newly established successor organization of the FN, the Forces républicaines de Côte d'Ivoire (FRCI), started a lightning offensive accompanied by massacres, which was quickly successful and resulted in the capture of large parts of Abidjan at the beginning of April. Gbagbo himself holed up with a hundred or two hundred of his loyal followers in the bunker of the presidential residence besieged by the FRCI, and other of his remaining troops, above all the Republican Guard (Ivory Coast) , offered massive resistance in the center of the metropolis. Intense fighting ensued, in which all sides used heavy weapons in the urban area. The units of the United Nations Operation on the Ivory Coast (ONUCI) and the French Opération Licorne intervened decisively on the side of Ouattara, which ultimately led to the arrest of Gbagbo on April 11 and the end of the conflict. As a result, however, there was tension and fighting between the FRCI and the Invisible Commandos, during which the leader of the Invisible Commandos, Ibrahim Coulibaly , was shot.

Ouattara's tenure

In 2011 the parliamentary elections in the country were peaceful. The Ouattaras party, the Rassemblement des Républicains won the majority of the votes. In 2013 Gbagbo had to answer before the International Criminal Court for "indirect complicity in crimes against humanity" .

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 438

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Andreas Mehler : Côte d'Ivoire: Chirac alone at home ?. Africa in focus (Institute for Africa Customers), number 4, Hamburg November 2004. ISSN 1619-3156

- ↑ BBC: Timeline: Ivory Coast. On-line

- ^ NZZ, November 9, 2004: Ongoing violence in Abidjan Online

- ^ Beyond Françafrique. How Paris' disastrous Africa policy ruined a continent

- ↑ a b c d Axel Biallas and Andreas Mehler: No elections in Côte d'Ivoire - peace process in a dead end. Africa in focus (Institute for Africa customers), number 4, Hamburg, October 2005. ISSN 1619-3156

- ↑ NZZ of November 3, 2006: Côte d'Ivoire's President remains in office. The UN Security Council extends Gbagbo's mandate for one year online

- ^ Neue Zürcher Zeitung, September 18, 2006.

- ^ NZZ, May 2, 2007: Hope for Peace in Côte d'Ivoire: Patrols of soldiers and rebels online

- ^ NZZ, July 30, 2007: Gesture of peace in Côte d'Ivoire: President visits former rebel area online

- ↑ The Standard: 480,000 new birth certificates issued online

- ↑ Der Standard: Electoral Commission: Opposition candidate wins presidential election , December 2, 2010.

- ^ Spiegel Online: Ivory Coast has two presidents , December 4, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.n-tv.de/politik/politik_kommentare/Elfenbeinkueste-Wehe-den-Besiegten-article10153031.html

literature

- Joseph Ki-Zerbo : The History of Black Africa. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-26417-0 .

- Basil Davidson: A History of West Africa 1000-1800. Revised edition, Longman 1978, ISBN 0-582-60340-4 .

- JB Webster, AA Boahen: Revolutionary Years: West Africa Since 1800 (Growth of African Civilization). Longman 1984, ISBN 0-582-60332-3 .

- Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes . Volume 2: West Africa and the islands in the Atlantic. Brandes & Appel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-86099-121-3 .