History of Togo

The history of Togo encompasses the history of today's territory of Togo .

The borders of today's Togo, however, are the result of a relatively young, colonial demarcation. Before the European colonization, the area was not an area with a delimited unified history.

Pre-colonial history

Since the 16th century, the coast of Togo was known as the beginning of the so-called slave coast because it served Europeans as a source for black African slaves . The small states of the south participated in the slave trade with the Europeans and thus profited from it. The peoples of the mountainous, central Togo, on the other hand, had to repeatedly evade the attacks of the black and Arab slave hunters. Again in contrast to the coasts to the west and east of today's Togo, due to the unfavorable natural conditions, European bases were not established until 1884, and only the place Aného achieved a modest importance as a trading center on the coast. A circumstance that was ultimately responsible for the development of modern Togo: The coast of Togo was the part of the West African coast that was still free from European influence at the end of the 19th century.

In northern Togo, the city of Sansanné-Mango stood out as a trading metropolis on one of the intra-African long-distance trade routes from the Sahel region to the south from the multitude of small towns.

In contrast to the surrounding areas, many smaller state units were founded on the territory of today's Togo in pre-colonial times. Large parts of the country were thus temporarily under the influence of the powerful empires of the Ashanti in the west or the Dahomey in the east in the 18th and 19th centuries . A few centuries ago groups of Ewe and Mina (also called Guin) immigrated to the south . The Ewe still keep the legendary memory of the reasons for their immigration from today's Benin or Nigeria . Their emigration is described as an escape from a tyrannical ruler. At no point did the Ewe organize themselves into larger state structures.

Colonial times

German protected area Togo

On July 5, 1884, individual places in today's Togo (or Bageida) were through a contract between a representative of King Mlapa III. and the German Consul General for West Africa, Gustav Nachtigal , declared a German “protected area”. On September 5, 1884, a " protection treaty " followed between the merchant Randad, who was appointed consul in Lomé, and the local king of Porto Seguro . In a protocol dated December 24, 1885, France recognized German rule over Anecho .

The demarcation to the neighboring colonies was made by the Franco-German Agreement of July 23, 1897 and the agreement on the demarcation between Togo and the French possessions in Dahomé (now Benin ) and the French Sudan of September 28, 1912 and the German- British treaties of July 1, 1890 and November 14, 1899. In 1914, the colony covered an area of 87,200 km².

In 1885 Ernst Falkenthal was appointed the first Imperial Commissioner based in Bagida . Under his aegis, a police force was founded on November 30, 1885. In 1889 he was replaced by Jesko von Puttkamer .

In 1886 German rule was extended to the areas of Towe, Kewe , Agotime and Agome - Palime , and in 1887 to Liati . From 1888 onwards, several expeditions took place in the more distant hinterland to manifest German sovereignty and to conclude further contracts with the local population. a. by Captain Curt von François (1888), medical officer Ludwig Wolf (1889), Hans Gruner and First Lieutenant Ernst von Carnap-Quernheimb (1894).

Inland stations were set up in Bismarckburg (1888), Misahöhe (1890), Kete Krachi (1894) and Sansanné-Mango (1896).

On July 18, 1905, the Lomé – Aného railway was the first railway line to open in Togo.

In 1914 there were eight administrative districts in Togo: Lomé City , Lomé Country, Anecho , Misahöhe, Atakpamé , Kete Krachi , Sokodé and Sansane-Mangu

League of Nations mandate and UN trust territory

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I , it was occupied by Great Britain and France. The German police surrendered on August 27, 1914.

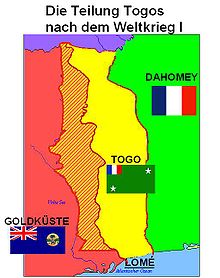

After the First World War, the eastern part of the colony, which is about two-thirds of the area has been accounted for, with the entire coast of France ( French Togoland ), the western part of the United Kingdom ( British Togoland ) as a League of Nations mandate passed, but in fact from the Gold Coast managed from , after the Second World War it became a UN trust territory .

In 1957 British Togoland joined the now independent Ghana . The French part received autonomy from France in 1955 . The women's suffrage was introduced 1956th

Independence and dictatorship of the Eyademas

On April 27, 1960, Togo finally gained full independence; first head of state was Sylvanus Olympio .

General Gnassingbé Eyadéma , who came to power as military chief in 1967, was Africa's longest ruling head of state. Behind the facade of free multi-party elections that were established in the early 1990s, the government has always remained under General Eyadéma's strong control. His party Rassemblement du peuple togolais (RPT) has been able to hold power almost continuously since 1967. A good friend of Eyadéma was Franz Josef Strauss , together they founded the Bavarian-Togo Society . A plane crash, which Eyadéma was the only passenger to survive in 1974, had far-reaching consequences. As a result of the glorification of Eyadéma and the glorification of the crash as an attack by the “international high finance”, Togo experienced a nationalistic jolt, in line with the continental trend. Economically, this meant a nationalization of the economically important phosphate mining , culturally a reflection on African names. Eyadéma gave up his first name Etienne and called himself Gnassingbé, and city names like Palimé, Bassari or Anécho became Kpalimé, Bassar and Aného.

From 1990 onwards the unrest in the Togolese population grew and violent protests broke out. Even under the pressure of the - in the face of obvious human rights violations and the discovery of 28 corpses shocked in a bay at Lome - had foreign Eyadema of convening agree to a national conference, with 1,000 delegates under the leadership of the Bishop of Attakpamé, Philippe Kpodzro , met and on 13 July 1991 declared their sovereignty. The interim government under Joseph Kokou Koffigoh failed, not least because Koffigoh did not consistently pursue the chosen course and after a short time negotiated with Eyadéma about the admission of old government members of the banned RPT into the newly formed government and Eyadéma in numerous attacks on opposition politicians Military used as leverage.

After the death of Gnassingbé Eyadéma on February 5, 2005, the country's army appointed his son Faure Gnassingbé as the new president. On February 25, he resigned under international pressure. The office was taken over by the President of Parliament. In the highly controversial election of April 24, 2005, Faure Gnassingbé was elected President. Riots with over 500 dead were the result. Tens of thousands of people fled Togo.

Togo came under pressure from many international organizations because of human rights violations , which led to many bilateral and multilateral development aid projects being frozen and only slowly being granted again.

Parliament unanimously decided on June 23, 2009 to abolish the death penalty; existing sentences have been commuted to life imprisonment. This made Togo the 94th country in the world to remove the death penalty from its law for all crimes.

In the 2010 presidential election in Togo and the 2015 presidential election in Togo , President Gnassingbé was re-elected with 60.9% and 58.75% of the vote, respectively.

In mid-August 2017, hundreds of thousands of Togolese protested in all major cities of the country against the rule of President Faure Gnassingbé. Despite the ban on demonstrations, thousands have taken to the streets almost every week to protest in the capital, Lomé . The police, on the other hand, regularly used tear gas , but live ammunition was also used. So far (as of November 4, 2017) 15 people have died in the conflicts, hundreds have been injured and an unknown number have been arrested. Amnesty International criticized the fact that numerous fundamental rights have been suspended since the protests. The opposition is calling for the president to resign, or at least for him to promise not to run again in the upcoming 2020 elections.

See also

literature

- German Colonial Lexicon , ed. by Heinrich Schnee, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920; Pp. 522-526. On-line

- Peter Sebald : Togo 1884–1914. A history of the German “model colony” based on official sources. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, 1988. ISBN 3-05-000248-4 .

- Ralph Erbar: A “place in the sun”? The administrative and economic history of the German colony Togo 1884–1914. ; Contributions to Colonial and Overseas History, 51; Stuttgart 1991

- Edward Graham Norris: The Re-education of the African. Togo 1895-1938 ; Munich: Trickster, 1993

- Johannes Thomas: Colonial Past. Does memory threaten to divide the nation? (Annotated Documentation) In: Documents. Zs. For the German-French dialogue , issue 2/2006; P. 60 ff .; on Togo: 69 ff. ( Sub-Saharan Africa ). The article documents the massive contradictions between the Federal Republic of Germany and France with regard to the rulers of Togo after 2000, contradictions that accumulated in the murders and the burning down of the Goethe Institute .

- Peter Sebald: The German Togo 1884-1914. Effects of foreign rule. CH Links Verlag, Berlin, 2013. ISBN 978-3-86153-693-2 .

- Rebekka Habermas : Scandal in Togo. A chapter of German colonial rule . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-397229-0 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 438

- ↑ Comi M. Toulabor: Le Togo sous Eyadema . Khartala, Paris 1986; ISBN 2-86537-150-6 .

- ↑ afrol.com: EU lifts ban on Togo (December 3, 2007)

- ↑ europa.eu: Declaration by the Presidency on behalf of the EU on the formal abolition of the death penalty in Togo (3 July 2009)

- ↑ amnesty.de : Togo abolishes the death penalty (June 25, 2009)

- ↑ John Zodzi: Togo leader Gnassingbe re-elected in disputed poll. Reuters , March 4, 2010, accessed November 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Togo's Faure Gnassingbe wins third term as president. BBC , April 29, 2015, accessed November 16, 2017 .

- ^ Johannes Dieterich: Togo's president feels the pressure of the citizens. In: The Standard . November 3, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017 .