History of Algeria

The history of Algeria began with the first human traces 1.78 million years ago, i.e. in the early Paleolithic .

Prehistory and early history

Early Paleolithic (from 1.78 million years old)

The oldest human traces of North Africa were found in Algeria. The artifacts of Aïn el-Hanech (mostly shortened to Ain Hanech in archaeological literature ) in northeast Algeria, about 12 km north-northwest of El Eulma, are around 1.78 million years old .

There were striking stones (cobbles), whole splinters (flakes), various fragments and retouched workpieces. The old age of the site has meanwhile been questioned, but has recently found advocates. In each case it could be shown that the makers of these tools lived in a savannah-like landscape and that meat was an important part of the diet. In addition to the remains of typical hunting prey such as rhinos and elephants , the bones of which show signs of processing, especially those of Equus tabeti , a species of horse, were found.

Excavations have been carried out for some time, leading to particularly early dated finds in various places in Morocco and Algeria; in Tunisia , however, only a single artifact from the time before by the leading form of so far has been hand-ax marked Acheulean , namely chopper or hackers. It is a piece of rubble from the early Paleolithic , the edge of which was created by machining an edge. Choppers are the oldest stone tools known to man and at the same time the first core tools .

In northern Algeria, in addition to Ain Hanech, the sites of Mansourah in the northeast, Djebel Meksem near Ain Hanech and Monts Tessala in the northwest are known. There are also sites in the Sahara such as Aoulef and Reggan in the middle of the country, then Saoura in the west and Bordj Tan Kena on the border with Libya . Most of the time, important stratigraphic information was missing , which led to premature and very early dates that can no longer be kept today. A major hurdle for more precise dating is the fact that the usual dating methods cannot be used, for example because there are no volcanoes in the region, the material of which would otherwise allow the determination of dating intervals.

Excavations in the years 1992–1993 and 1998–1999 led to the result that Ain Hanech is not a single site, but that there are four sites on an area of around one square kilometer. These are next to Ain Boucherit, which is about 200 m southeast of Ain Hanech west of the eponymous Ain Boucherit stream, the El-Kherba and El-Beidha sites, which are 300 and 800 m south of the classic sites, respectively. Paleomagnetic investigations determined an age of 1.95 to 1.77 million years for the relevant layer in Ain Hanech, where numerous artifacts were discovered on a former stream. The Oldowan artefacts discovered up to 2006 are located in a layer in which no traces of the Acheuléen appeared, so that this settlement phase is not related to the oldest finds. 2475 often very small archaeological finds representing processing waste, plus 1243 bones and 1232 stone artifacts were found in Ain Hanech. 631 pieces were found in El-Kherba, including 361 bones and 270 stone artifacts. In almost all cases, limestone and flint are the starting materials (43 and 56%, respectively), while quartzite and sandstone are extremely rare. Flint, which is even more common in El-Kherba, is mostly black here, occasionally green. Flint cores are consistently smaller than those made of limestone, the cuts are very small, even if the largest is 106 mm. In Ain Hanech, 411 retouched pieces were found, mostly scratches (50%) and denticulates (32%) retouched on the narrow sides , i.e. toothed devices, then end-scrapers, i.e. narrow blades or knives with at least one convex side for scraping (8, 5%), and finally devices with notches or notches (7%); very rarely are graver , hand axes were not found. Ain Hanech represents the oldest known stone processing technology (mode 1) and is therefore the only excavation site in North Africa to be part of the Oldowan; the finds were completely separate from those of the Acheuléen, which were six meters further above.

The remains of large mammals, such as giraffes and hippos, which were surrounded by stone artefacts, were difficult to interpret at both Algerian sites . In addition to the animal species known since the first excavations, there were new discoveries, such as Equus numidicus . Overall, the finds and the traces of blows and cuts that can be found on them represent the oldest evidence of the cutting up of larger animals in North Africa.

Acheuleans

In addition to the sites near Casablanca , Tighenif in western Algeria is the most important archaeological site in the north-west. The oldest human remains of Algeria discovered there are around a million years younger than the aforementioned traces. The lower jaw of Ternifine (today: Tighénif) was discovered in 1954 in a quarry 20 km east of Muaskar in the north-west of the country and initially referred to as Atlanthropus mauritanicus , today more as Homo erectus mauritanicus or Homo mauritanicus . It has been dated to be approximately 700,000 years old. This makes it the oldest human remains in Northwest Africa. They consist of three lower jaws (Tighénif 1, 2, 3), a parietal bone (Tighénif 4) and several teeth, four of which probably come from an 8 to 10 year old child. The fauna still consisted of mammals such as the elephant Loxodonta , the rhinoceros Ceratotherium and various species of antelope. The landscape should have been open, but there was enough water. Some signs point to a cooling, which can be recognized by the immigration of steppe inhabitants.

The Acheuléen, to which the find can be assigned, began about 1.75 million years ago in East Africa and is associated with the appearance of Homo erectus . The leading artifact is the hand ax . While the Developed Oldowan was divided into two phases until a few years ago , the assignment of the second section of this phase to the Acheuléen has largely prevailed. Manufacturing technology shifted from small, often rough cores to larger ones that allowed the manufacture of larger tools. New materials and new machining techniques required greater strength and precision, as well as better coordination.

The late Acheuléen can also be found in Algeria, for example at Lac Karar in the northwest; Here, on the basis of softer processing strokes, lancet- and heart-shaped hand axes, cleavers (a special shape of rectangular hand axes), plus large and small cuts, were created.

With Saoura and Tabelbala-Tachenghit, the Acheuléen is also represented in the Sahara , which offered much more favorable living conditions at that time. In addition to rubble devices, raw trihedrons (tripods), rarely hand axes , tees and cores appear in the early phase . The thick hand axes, made with greater effort, remained in use here longer than in the north. Cleavers are already numerous in this phase between 1,000,000 and 600,000 years ago, and the levallois technique came into use. After that, the devices became finer, cleavers continued to dominate, a Tabelbala-Tachenghit technique, a pre-Levallois technique, emerged. A little further to the west, in the Tarfaya region, there were also indications of the Levallois technique, but the small number of finds could point to a slow disappearance of the Acheuléen. In Tihodaine , near the Tassili-n'Ajjer plateau, is one of the rare sites where animal remains with Acheulean artifacts occur. Their age has been determined to be at least 250,000 years, similar to Sidi Zin in Tunisia.

Atérien (more than 100,000 to 30,000 BC ago), anatomically modern human

The carrier of the North African Atérien culture was anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ), although the culture may not have been developed until the Maghreb. According to Moroccan finds, this happened between 145,000 and 171,000 years ago. The Atérien thus has a key position in the question of the spread of Homo sapiens in the Maghreb and (possibly) Europe. In any case, in the Maghreb, the later hand ax complexes were followed by the teeing industries , which were very similar to those in southern Europe and Asia.

The Atérien, named after the site of Bi'r al-'Atir southeast of Constantine , was long considered part of the Moustérien , analogous to Western European developments. However, it is now considered a specific archaeological culture of the Maghreb, which reached a very high level of processing of its stone tools.

She developed a handle for tools, combining different materials to make composite tools. The main shape is the atérien tip equipped with a kind of mandrel, which is suitable for being fastened in a second tool part. Already in 1886 it was recognized as a separate archaeological culture through excavations in the Eckmuhl quarry (Carrière d'Eckmuhl, a suburb of Oran ). In the early 1920s it was named Atérien. Although the bearers of this culture were modern people, they came to the Maghreb at the latest 80,000 years ago, as the skull of Dar es-Soltan shows.

It is possible that the first anatomically modern humans did not come to the Maghreb with the Atérien culture, but developed it on site. The oldest find of human remains of this kind in Morocco is 190,000 to 160,000 years old (Djebel Irhoud) and is thus before the previous borders of the Atérien. There were found Moustérien artifacts, but no typical artifacts of the Atérien.

It is possible that a cultural loss can be established in the late Atérien, because so far there is no known evidence of (body) jewelry such as was found in the Grotto des Pigeon near Taforalt in the Oujda region in eastern Morocco. Thirteen pierced snail shells were discovered there, which were dated to an age of 82,000 years. The shells were transported 40 km from the Mediterranean Sea, decorated with ocher and pierced in such a way that they could be worn as a chain. They are considered the oldest symbolic object. Some archaeologists ascribe the emergence of a symbolic level to modern humans, as it were as a biologically determined genetic material , while others already see this pattern among the Neanderthals in Eurasia . In addition to biological approaches, cultural or climatic causes are also discussed.

Epipalaeolithic (until 6000 BC)

The period from around 25,000 to 6,000 BC In the Maghreb, BC includes both hunter-gatherer cultures and those of the earliest transition to the sedentary, rural way of life. As in many regions of the Mediterranean, the transition to arable farming was preceded by a long phase of increasing locality, which was the prerequisite for the adoption of agricultural techniques, but cannot, as it were, explain its development backwards. In each case, this long-term development was strongly determined by climate changes.

The glaciations of the last glacial period did not reach the North African coast, but colder northwest winds led to a drier climate. Pollen studies have shown the increase in steppe plants in the region. The Ifrah Lake in the Middle Atlas offers pollen finds from the period between 25,000 and 5,000 BP . They in turn show that the temperature during the last glacial maximum (21,000 to 19,000 BP) was on average 15 ° C lower and the precipitation was around 300 mm per year. During this time, even the Atlas cedar ( Cedrus atlantica ) disappeared , although oaks can still be detected. From 13,000 BP, temperature and precipitation rose slowly, between 11,000 and 9000 BP there was a further cooling. In the Algerian Chataigneraie, not to be confused with the French, it was shown that the cedar fell sharply with the sharp rise in temperature and humidity by 9000 BP, an increase that continued to around 6500 BP.

Ibéromaurusia (17,000 to 8,000 BC): beginning to settle down

The Ibéromaurus , a culture widespread on the North African coast and in the hinterland, spread between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. On the entire Maghrebian coast. An important site is Afalou Bou-Rhummel near Bejaia , but above all the Moroccan Ifri n'Ammar .

The Ibéromaurus is the oldest stage of the Maghrebian Epipalaeolithic ; it extends from 17,000 to 8,000 BC. Their distinctive artifacts, microlithic back tips , were found between Morocco and the Cyrenaica , but not in parts of western Libya. To the south it stretched far into the Atlas , in Morocco even as far as the Agadir region (Cap Rhir). The lithic industry of Ibéromaurusien was based on blades; back tips that were processed into composite tools, for example in pairs to form glued, double-edged arrowheads, are particularly common. The proportion of the tips of the back regularly makes up 40 to 80% of stone tools.

In addition to the lithic industry, a highly developed bone technology emerged. The bones were made into small tips, but also decorated. In addition, mussel shells were processed, apparently not into jewelry, but rather - even up to 40 km from the coast - as components of water containers or as leftover food. In Afalou there were animal-shaped figurines made of clay and fired at 500 to 800 ° C (in a simpler form also in Tamar Hat ), but stone carvings were also found, for example on blowstones , such as the mane sheep from Taforalt .

The mane sheep, which is a goat-like species , was an important source of food. In Tamar Hat, 94% of the ungulate bones were found, which led to considerations as to whether the animals could not have been herded. In any case, it must have been a highly specialized form of hunting. It is controversial whether this type of controlled keeping or hunting came into practice in times of greater drought, only to be given up again in favor of previously common forms of hunting when the humidity increased.

In Algeria, the main sites are first to be found around the Moroccan-Algerian border ( Ifri El Baroud , Ifri n'Ammar, Kifan Bel Ghomari, Taforalt, Le Mouillah, Rachegoun), then along the coast (Rassel, Afalou, Tamar Hat, Taza) , finally a few sites in the hinterland ( Columnata , El Hamel, El Honçor, Dakhlat es Saâdane, Aïn Naga), and finally on the Algerian-Tunisian border (Khanguet El-Mouhaâd, Aïn Misteheiya, Relilaï, Kef Zoura D, El Mekta). The cultures that preceded Iberomaurus vary regionally, in Taforalt it replaces an industry without discounts. In Iberomaurus, differences in stone technology between the coast and the hinterland could be demonstrated, and people in stone processing technology also reacted in different ways to differing ecological niches.

The emergence of the Iberomaurian could be related to the spread of the dorsal blades , which occurred around 23,000 to 20,000 BP , as they covered large parts of the Middle East and North Africa. It is unclear whether it spread from east to west along the coast or on a more southerly route. The culture can be detected up to 11,000 BP, probably even up to 9500 BP.

The oldest burial sites come from the Algerian sites of Afalou-bou-Rhummel and Columnata. Anatomically, the dead belonged to modern man, but were built robustly. They were classified as " Mechta-Afalou " by Marcellin Boule and Henri V. Valois in 1932 , but today it is considered refuted that it was a separate "breed". In any case, this was assigned to the Guanches of the Canary Islands without further evidence . Against this classification, the fact that this type, observed exclusively on the basis of anatomical features and appropriately sorted skeletons, also appears in Libya, where it was assigned to a different culture, but also in the Capsia sites in Tunisia and Algeria. In 1955 the "Mechta-Afalou breed" was even differentiated into four sub-types by sorting on the basis of mere visual appearance. Around 1970 further "races" were defined in this way.

The removal of mostly healthy teeth is noticeable, e.g. B. in the skull of Hattab II, especially the incisors. Since there are no other traces of violence in the facial area, this was probably due to cosmetic, ritual or social reasons, such as status reasons.

At around 13,000 BP, large piles of rubbish were produced, most of which were made up of the shells of molluscs . They were found in caves in the western Maghreb and appeared a little before the capsia sites in Algeria and Tunisia, the escargotières . Whether these mounds are signs of increased local stability, similar to the growing number of burial sites, is still being investigated.

Capsien (around 8000 to 4000 BC)

In Eastern Algeria and Tunisia, Iberomaurus was followed by Capsia, which became known in 1909 with the discovery of the Mekta site near Gafsa in southern Tunisia. In 1933, R. Vaufrey proposed a division into typical and upper capsien , a division that is still valid today.

While large tools predominated in the earlier phase, (geometric) microliths dominated in the later phase . The boundary between the two phases, which coincided with the appearance of a changed manufacturing technique for blades, the pression pour le débitage lamellaire or pressure-flaked bladelets , could be around 6200 cal BC. Chr. Lie. The typical capsien (from 9400 to 9100 BP) was followed by an upper capsien (from 8200 BP). His new technique, in which blades were obtained less by striking than by pressure, is associated with a considerable refinement of stone technology, but it is also an indication of a change in lifestyle.

As can be proven in Hergla in northern Tunisia, the hunters, fishermen and gatherers there were able to process obsidian in addition to the predominant limestone and flint in the first half of the 6th millennium . This volcanic, glass-like material can only have come over the sea, so that it can be regarded as reliable evidence of seafaring, which at the latest at the turn of the 7th to 6th millennium BC. Must have started. In the western Mediterranean, the eastern obsidian areas, such as Anatolia , are out of the question; the Carpathian obsidian only extended westward to Trieste in northern Italy . So only Pantelleria , Palmarola , Lipari and Sardinia were eligible . Chemical tests have shown that the material came from the island of Pantelleria. The processing was evidently carried out in a similar way as one was used to with stone tools.

In contrast to Iberomaurusia, which also knew rubbish hills, such hills now arose in which organic remains held up comparatively well, now as hills visible in the landscape, not only in caves. Most of the human remains have been discovered in these hills, the escargotières . The removal of the incisors was much rarer than before, after the Iberomaurus it was mainly restricted to women. In this regard, regionally different practices can be identified around 9500 BP.

In Hergla, northern Tunisia, the manufacture of ceramics in situ has also been demonstrated. This means that the ceramics are also here earlier than the beginning Neolithic, as can already be proven in the Middle East and in numerous other areas. Pre-Neolithic pottery was found in El Mermouta and El Mirador in northern Algeria. Apparently the hunters, fishermen and gatherers adopted Neolithic innovations, but stuck with their previous lifestyle. In addition, there was a kind of long-distance trade or exchange, including by sea, technological innovations and limited settlements, as well as the formation of food stocks. In Aïn Misteheyia in eastern Algeria, the adaptability of these societies to climatic changes has been demonstrated. Possibly the people of the Capsien belong to the ancestors of the Berbers.

Neolithic (before 5600 BC)

For some time, cereal grains were kept in ceramic layers as a sign of early Neolithic Morocco. The plants and animals, but also the impresso goods, came from southern Spain. The process began later in eastern Morocco and Algeria. Sites like Hassi Ouenzga show that diversified ceramics of local types first appeared, then domesticated animals.

The data determined up to 2012 for ancient Neolithic finds from the "Rif Oriental" project extend to 5600 BC. BC, the latest data from the coastal stations are probably even older. The Ifri Ouzabor site shows an epipalaeolithic layer under the Early Neolithic. The finds of the upper layer are already here around 6500 BC. And are therefore a thousand years younger than the previous end date of Ibéromaurusien in the hinterland of the coast (Ifri el-Baroud). It is possible that the sought-after continuity of the Epipalaeolithic to the Early Neolithic can be proven here.

In any case, there seems to have been no continuity between the hunter-gatherer cultures and the Neolithic cultures in the west and north of Morocco. However, the custom of removing the front teeth persisted. While it was now seldom found in the east of the Maghreb, it was present in 71% of individuals in the west and again affected men and women equally. This may speak for a continuity of the population.

The oldest rock carvings in the Maghreb were found at Ain Sefra and Tiout . On the mountain slopes of Mont Ksour up to El Bayadh there were pictures of ostriches, elephants and people. There are five phases in these rock art. From 9000 to 6000 BC The main engravings were made in the Bubalus phase, named after the Asian water buffalo ( Bubalus ). This was followed by the first paintings (round head, 7000 to 6000 BC), followed by fine depictions of cattle, other domestic animals and people in the cattle era (4000 to 2000 BC). Corresponding depictions follow in the horse period (2500–1500 BC) and in the camel period (from 100 BC).

Libyans, Berbers, Imazighen

Perhaps since the Capsien, cultures of considerable continuity can be detected, which were later referred to as Libyans or their ancestors and which were long referred to as Berbers . However, this is not considered certain, which is why many authors prefer the traditional term “Libyan”, which was used quite differently by the Greeks. Due to the adoption of the Latin word for those who did not speak Latin, namely barbari , which in turn was transferred to the non-Arabic-speaking population, the region was often referred to as "barbaric". The "Berbers" call themselves Imazighen (singular: Amazigh).

From around 2500 BC The Sahara became drier again, which forced numerous groups to seek out more favorable areas, and many more areas became uninhabitable. Around 1500 BC The Middle Eastern influence grew stronger, with numerous rock carvings depicting horses and chariots on the Garamanten road .

Large burial mounds were found in Algeria , which, like in Mzora , had a diameter of up to 54 m. They can probably be assigned to the first millennium BC. The later tumuli already show Phoenician influences, although the hills date back to Libyans. A mausoleum known as Medracen probably dates from the 4th or 3rd century BC. Chr. And has a base diameter of 58.9 m. Several of the buildings from the pre-Islamic Berber period were presented to UNESCO as candidates for a World Heritage Site in 2002.

Written sources only set in the 2nd century BC. A. At that time, the Berber culture had not only become strongly regionalized, but was in constant exchange with the cultures of the Sahel , with Egypt and across the Mediterranean with southern Europe and the Middle East. Only in this stage of increasing sedentariness, the emergence of villages with large necropolises and a corresponding architecture of the tombs, the emergence of tribal , later monarchical traditions as well as the influence of Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans and the emergence of our own script do we receive albeit dry written records.

In Chemtou , the ancient Simitthus in the northwest of Tunisia, there were bas-reliefs. It is possible that the depictions were local gods, similar to Béja, where the depictions probably date from the 3rd century AD. However, while in Borj Hellal from the 1st century BC A goddess is still in the center of attention in BC, the male counterpart is already in the center of attention in Beja , which is four centuries younger . Nevertheless, as Roman sources attest, the dii mauri , the Moorish gods, persisted.

In addition to these gods, Baal Hammon and Tanit played the central roles in the Phoenician regions . However, the goddess Tanit played almost no role among the Libyans. The influence of the Punic religion on the Berbers was reinterpreted early in research. Until our century, the historical imagination was all too often determined by the view of the Carthaginian human sacrifices, which cannot be dismissed there. But only one source pointed to such sacrifices among the Libyans. These Mauri , Maurusii , Masylii etc. were considered friendly by the Eastern Romans . For the hostile Berbers, however, names like Nasamon or Marmarides came into use at this time , groups that lived in the area of today's state of Libya. As evidence for human sacrifice, which is supposed to have existed until the 6th century AD, the often cited passage in Goripp is not, however, as recent studies show.

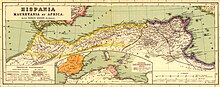

Carthage, Mauritania and Numidia

The areas of Algeria have been settled by Berbers since the beginning of historical tradition. Towards the end of the 3rd century BC The Kingdom of Numidia in the east and the Kingdom of Mauritania , which included northern Morocco as well as western Algeria, came into being.

Around 600 BC The trading metropolis Carthage dominated , which according to legend 814 BC. BC by Phoenicians had been developing. The city secured a spacious hinterland. At the latest by 580 BC it came to grief. BC with the Greek colonists in Sicily in conflicts that flared up again and again, which sparked off in the Carthaginian-Phoenician colonies in the west of the island and in trade competition. A chain of bases reached as far as the Atlantic coast, some of them were foundations of Carthage, such as Hippo Regius , Bejaia or Tipasa .

Mauritania, Massyler and Masaesyler

Expansion of Carthage, First Punic War, Mercenary War (until 237 BC)

Around 250 BC The Carthaginians advanced on the plateau of Theveste in the extreme east of Algeria.

In the middle of the first war against Rome , Hanno undertook in 247 BC An expedition to the west that took him to Theveste, while Hamilkar Barkas sailed to Sicily. Possibly took place after the mercenary war - it found 241-237 BC. After the end of the First Punic War - another Numidic War took place. Or maybe it was just the crackdown on those Numidians who had joined the mercenary uprising. It is unclear to what extent this external pressure caused the Berber groups to establish a royal rule.

The Second Punic War, Massinissa and Syphax (until 202 BC)

Gaia, the father of Massinissa , was probably the first king of the Massylers, the easternmost of the three Numider kingdoms. The narrow area lay between the area of Carthage and that of the Masaesylers, with the border town of Cirta , today's Constantine , repeatedly causing fights between the two Numider empires. Among the Massylers, the proportion of the permanent rural population was considerably higher than further to the west. Gaia's son Massinissa was raised in Carthage and had access to the highest circles there. He was trained in Punic war techniques and allied himself with Carthage in the fight against Syphax , the king of western Numidia, during the Second Punic War . He attacked Syphax together with a Punic army under Hasdrubal and forced the Roman allies to make peace with Carthage. 212 BC He crossed over to Spain with Hasdrubal, where he and his Numidian horsemen made a decisive contribution to the victory over the Romans under the brothers Publius Cornelius Scipio and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus . 213 BC However, Syphax had changed the front and allied himself with the Romans, so that the Carthaginians had to quickly withdraw from Spain. The Carthaginians, for their part, sought a rapprochement with Gaia. Both sides tried to get Syphax to their side.

When Hasdrubal married his daughter Sophoniba to Syphax out of political calculation, namely to finally win him over as an ally, and when he also offered him the prospect of a successor to Gaia, Massinissa changed in 206 BC. On the side of Rome. But he was defeated by Syphax and driven out of eastern Numidia. His inheritance claim was also by no means secured. According to agnatic law, Gaia had appointed his brother Oezalces as his successor, but the old man soon died. However, he had two sons; the younger was a minor so that Capussa ascended the throne. Mazaetulla , who belonged to a warring line of the royal family, rose against the new king . In the fight between the pretenders, Capussa was killed. The victor transferred the throne to the dead brother's underage brother, Lacumaces , but Mazaetulla retained real power as guardian and regent. In addition, he married the widow of King Oezalces, a Carthaginian woman.

After these events, Massinissa crossed from Gades in southern Spain to Numidia without knowing how to return with his few men. King Baga of Mauritania asked him - he did not want to be drawn into the war between Rome and Carthage - 4,000 men at his disposal, who escorted him through the kingdom of Syphax and then withdrew. Massinissa established itself in Carthaginian territory and waged a guerrilla war there, which, however, was extremely costly for Carthage. Mazaetulla sent 4,000 soldiers and 2,000 horsemen under his general Buscar, who were so successful that Massinissa was able to escape with only 50 horsemen. But he was surrounded again at Clupa ( Kelibia ) and cut down to five men. Massinissa escaped and threw himself into a river with his few remaining ones. He was considered drowned, two of his four men were killed. Syphax was now the lord of both Numider realms.

But Massinissa was hiding in a cave where his men looked after him. When he set out to recapture his empire, he quickly found supporters among the Massylers. Soon he had 6,000 foot soldiers and 4,000 horsemen at his disposal again. He occupied strategically important heights between Cirta and Hippo Regius . But against the army of Verminas , the son of Syphax, Massinissa suffered a crushing defeat. Syphax allied itself in 204 BC. Finally with Carthage, for which his Carthaginian wife Sophoniba had set everything in motion. But only in the event of a war in Africa was Syphax obliged to support Carthage, not for the struggle across the Mediterranean.

When Scipio the Elder in 204 BC After landing in Africa, Massinissa came to the Roman military leader as an almost destitute refugee. When Syphax appeared with an army, Scipio had to break off the siege of Carthage. However, he let the opponents who stayed overnight in Numidian mapalia attack and burn down their huts. He himself attacked Hasdrubal's camp. Massinissa certainly contributed to the victory over Hasdrubal and Syphax in the attack. Together with Laelius , Massinissa fell into the realm of Syphax that same year. Hasdrubal and Syphax, who had a total of 30,000 men under arms, of whom 6000 were Celtiberians, finally lost in the plain of the Bagrada. Hasdrubal fled to Carthage, Syphax to Numidia. The returned Hannibal was finally defeated by Zama and had to 193 BC. Flee from Carthage. Carthage's territory was limited to Africa, the city had to deliver 10,000 talents of silver to Rome over the next 50 years , and the fleet had to be delivered up to ten ships. Carthage was officially declared an ally when Rome waged war against Macedonia and the Seleucids . The city even supplied grain and provided six of its ten ships. For Numidia, besides this power restriction, the most important contractual clause was that Carthage could no longer wage war without Roman consent.

Roman client kingdom Numidia (from 202 BC)

Scipio left Massinissa probably a third of the Roman army in order to enforce his inheritance claim against Syphax. He left the Roman troops behind to take Cirta, which only surrendered after Syphax had been brought up as a prisoner. Sophoniba, who was also captured by Massinissas, he tried to protect from Scipio's demands by immediately marrying her. She was already known to him as a child in 213 BC. Was promised. In the extradition claim against Massinissa, she herself argued that the Numidians and Carthaginians were Africans, which was supposed to unite them against the Roman invaders. Scipio also recognized after questioning the Syphax, who shifted all the blame on Sophoniba, that the Carthaginian was an implacable enemy of Rome. When Scipio requested her extradition, Massinissa handed her the poison cup herself. Rome recognized Massinissa as King of Numidia. As a reward for the services rendered, he received the kingdom of Syphax. The valley of the Bagradas had to cede to Carthage again, any resistance to his demands was threatened by Rome with a reopening of the war. Cirta became the capital of Numidia.

Massinissa first abolished the agnatic succession to the throne in order to secure the succession to his sons. Like Vermina before him, he had coins minted with his portrait , he wore a diadem according to the Hellenistic model and made sure that the eldest son was appointed heir to the throne. Especially in the west, where Vermina disappeared in an unknown way, the possibilities of rule were very limited. Towards the end of his reign he was faced with the uprising of a grandson of Syphax named Arcobarzanes . First, however, Massinissa encountered between 200 and 193 BC. BC to the west against Vermina, while Baga remained neutral. 195 or 193 BC Chr. Massinissa, who reclaimed the territory owned by his father Gaia, attacked Carthaginian places. 182 BC There was another attempt at expansion, again envoys from both parties went to Rome. Massinissa had to surrender the 70 cities he had conquered according to the Carthaginian complaint, but occupied them again a few years later. Much later he succeeded in 161 BC The occupation of the city of Lepcis, later Leptis Magna in Tripolitania .

Third Punic War, division of the Numider Empire (150 to 118 BC)

151 BC The Massinissas party was driven out of Carthage. However, Hasdrubal's army was defeated by Massinissa. The general had to promise to forego all disputed territory and to pay 5000 talents of silver. The rest of his army was disarmed and had to withdraw without weapons, but was attacked and killed on the way by Gulussa , Massinissa's son. Massinissa supported the Romans who ruled the city in 146 BC. Destroyed, reluctantly against Carthage. He died right at the beginning of the war in 149 BC. At the age of 90 years. At his request, Scipio the Younger divided his kingdom among the king's sons Micipsa (until 118 BC), Gulussa and Mastanabal .

Succession dispute and Jugurthin War (118 to 105 BC)

Micipsa initially played an important role in the further development; he survived his two brothers and, after thirty years of reign, in 118 BC. BC died. But his brother Mastanabal had two sons who played an even more important role in the dynastic development, namely Jugurtha , who was 118/112 to 105, and Gauda , who was 105 to 88 BC. Was king of Numidia.

After Micipsa's death, his sons Adherbal and Hiempsal and his nephew Jugurtha, whom he had adopted, were to become his successors and divide Numidia into three domains. Jugurtha, in contrast to his half-brothers Adherbal and Hiempsal, did not descend from Micipsa's favorite wife, which excluded him from his rightful claim to the throne. Micipsa felt compelled to send him to Spain, where he helped in the siege of Numantia at the side of his future opponent Marius .

As Micipsa 118 BC Died, the expected dispute for heir to the throne broke out. During negotiations, Jugurtha had Hiempsal murdered, but Adherbal was able to flee. 116 BC After Jugurtha had bribed the right men in Rome, Rome agreed to partition Numidia between Jugurtha and Adherbal. In 112 Jugurtha attacked the capital Cirta and had Adherbal executed along with the entire male population of the city. Roman traders were also killed, forcing the Senate to intervene.

But even the military operations that led to the Jugurthin War were only carried out half-heartedly, because Jugurtha controlled part of the Roman upper class. 111 BC BC Consul Lucius Calpurnius Bestia went to Numidia, but he concluded a peace that was advantageous for Jugurtha. Thereupon the tribune invited Gaius Memmius Jugurtha to Rome, where he was supposed to give an account before a popular assembly about whether he had not bought the advantageous conditions. The fact that this hearing should not take place in front of the Senate but in front of a popular assembly was a break with Rome's foreign policy tradition and also an indicator of the political tensions. Jugurtha did come to Rome, but the assembly waived the veto of a tribune's questioning. When Jugurtha had a possible rival murdered in Numidia from Rome, he had to flee Rome. After his return to Numidia, Jugurtha is said to have uttered the sentence that everything and everyone in Rome can be bought.

Beginning of 109 BC Rome suffered a serious defeat in Numidia when Aulus Postumius and his army were forced to surrender. Jugurtha demanded an extremely generous treaty with Rome as a peace condition, in which he would have been made a foedus (ally), which should secure his usurped power to the outside world. But the contract was not recognized by the Senate. A new commander should end the war. 107 BC BC Gaius Marius was elected consul and charged with suppressing the Jugurtha uprising. He reformed the army first and his newly formed army was able to defeat the Numid several times, so that Jugurtha had to flee to Mauritania. One of Marius' commanders named Sulla , negotiated the extradition of Jugurtha from his father-in-law Bocchus I of Mauritania . Jugurtha was executed in Rome in the Tullianum . Gauda , a half-brother of Jugurthas, and Bocchus inherited his empire .

Gauda was followed by his son Hiempsal II , to whom Marius fled from Sulla. But there he was imprisoned and could only free himself with the help of the king's daughter. The Marian party under Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus raised a Numid named Hiarbas against Hiempsal, who lived in 81 BC. Was overthrown. Thereupon Gnaeus Pompeius sailed to Africa to reinstate the king. According to Sallust (Jugurtha, 17) the king was the author of a Numidian story in the Punic language.

Caesar, Pompey, Juba I. - End of the Numidian monarchies (46 and 33 BC)

Juba I , a son of Hiempsal II, ruled around 60 BC. BC to 46 BC The Kingdom of Numidia. When the Roman civil war broke out between Caesar and Pompey , Juba allied himself with the latter. He destroyed 49 BC The army of Gaius Scribonius Curio fighting for Caesar . But three years later he was defeated with the supporters of the now dead Pompey in the battle of Thapsus . Juba fled towards Numidia, but his capital Cirta refused entry. In a hopeless situation, the king arranged a duel with his companion, Marcus Petreius , in which both were killed.

Bocchus I, who lived until 108 BC. He had kept neutral afterwards Jugurtha, who had promised him a third of his empire, supported him, but 105 BC. He had handed it over to the Romans. They now recognized him as a "friend of the Roman people". After his death in 80 BC His sons Bocchus II and Bogudes followed him . After the death of the latter, the divided Mauritania, whose western part Bogudes had ruled, was reunited. But with the death of Bochus II, Mauritania fell in 33 BC. At Rome.

Part of the Roman Empire

Provinces, border security, urbanization in the north

After Caesar's victory over the Pompeians and thus over Juba I, the Massylian empire was divided up and huge state estates arose. The eastern part of East Massylia became part of the Africa nova province newly created by Caesar . The western part of East Massylia, i.e. the area around Cirta, went to the adventurer Publius Sittius , who distributed the land to his soldiers and established a Roman colony , the Colonia Cirta Sittianorum . Bocchus II of Mauritania, a friend of Sittius and also an ally of Caesar in the war against Juba, received Western Massylia and Eastern Massylia, i.e. the area around Sitifis .

The Kingdom of Mauritania was founded in 33 BC. Chr. Bequeathed to Rome in will by King Bocchus II. Augustus put Juba II in 25 BC. As ruler over the resulting Roman client state . In 23 AD his son Ptolemy followed him to the throne. He put down a revolt directed against Rome. On the occasion of Ptolemy's visit to Rome, Emperor Caligula had him murdered in AD 40. He annexed the leaderless empire, and the resistance to the occupation was suppressed that same year. Claudius divided the territory of the former kingdom into the provinces of Mauretania Caesariensis with the capital Caesarea ( Cherchell ) and Mauretania Tingitana with the capital Volubilis .

With the Limes Mauretaniae an attempt was made to secure the southern border of Mauritania and Numidia in the long term, similar to other borders of the empire. The Limes of the two Mauritanian provinces, however , was not conceivable as a continuous fortified border wall because of the enormous length of the border, which stretched from the Atlantic to the eastern border of the Caesariensis province. Instead, barriers (clausurae) were primarily built in the valleys of the Atlas, as well as trenches (fossata), ramparts, but also a number of watchtowers and forts. The facilities were connected by a road network designed according to strategic aspects. Depending on the type of cooperation with the individual trunks, you could either dispense with backups or thin them out. The expansion of the border was intensified at the beginning of the 1st century AD and extended the borders further south until the 3rd century.

To the north of Schott el Hodna , a salt lake in the area of the central Algerian Monts du Hodna, there were a number of clausurae, which consisted of ramparts, adobe walls or rampart and ditch systems up to a length of 60 km and thus narrowed the valley passages . The area of the province of Mauretania Caesariensis was secured by a line of fortifications running along the 700 km long cheliff , which consisted of a series of forts built under Hadrian , about 30 to 50 km apart. In the north-west of the province, the Rif Mountains drop steeply into the sea and thus interrupt the land route between the provinces. The Severians had a number of forts built in the western Caesariensis. The last fort in this series was Numerus Syrorum ( Maghnia ), which was in the extreme west of the province in front of the Tlemcen Mountains. The Hadrianic chain of fort on the Cheliff River now served as an additional barrier and containment line.

The most important city in the Roman Numidia was next to the Municipium Lambaesis , under Septimius Severus capital of the province of Numidia and Philip the Arab colony was the colony Thamugadi . In contrast to Lambaesis, Thamugadi was founded as a new foundation in a previously uninhabited place. The old capital of the Syphax, Cirta, which became a colony whose territory included Tiddis , about 15 km away , was also of importance.

240 Sabinianus was proclaimed emperor in Carthage; his estates were near Thysdrus and his father had made his fortune by exporting olive oil to Italy. The usurpation was put down by the governor of Mauritania that same year.

Roman religion

The Roman religion came to North Africa mainly in the form of the triad Jupiter , Juno and Minerva . Even Mars played an important role as a god of war in certain environments it came up since Augustus the imperial cult . In addition to the official religion, the worship of old gods continued, who only received the new names. The Roman gods, for their part, were modified in the new environment. Saturn and Baal , Caelestis and Tanit could thus merge.

Christianization (from around 200)

Donatists

When the Donatists came up, they supported many insurgent Berbers, such as Firmus or his brother Gildon in 396. They went back to Donatus of Carthage . He was primate of the group from 315 to 355 . When the Roman Church took in those who had fallen away under the pressure of persecution, the Donatists, who refused to take up again, parted with the Church, which was close to Rome. A group of Donatists, the agonists , which Augustine of Hippo disparagingly referred to as "circumcellions", as "drifters", combined religious and social protest and tried to enforce their ideas of equality by force until the 7th century. This escalation was triggered by a colonial uprising in 320. Due to the conflict with the Donatists, Augustine, who was Bishop of Hippo from 395 to 430 , became the leading figure in the African Church. He also used state violence to persecute and convert the Donatists.

Tombs of Tiaret (Djedars)

French archeology uses the archaeological term “djedar” to describe thirteen tombs about 30 km south of Tiaret with Christian iconography . Three of them were found on Jabal Lakhdar , ten on Jabal Arawi , 6 km further south. There are great similarities with the older, smaller Berber bazinas , so that the larger structures go back to Berber traditions despite Christian iconography and the use of Roman construction techniques. It is unclear whether the dynasts in the region were themselves Christians, or just their subjects. In the large Djedars, which are up to 46 m long and originally up to 13 m high, there were burial chambers. The tomb complexes were surrounded by low walls. The few Latin inscriptions are almost illegible. The largest Djedar contains inscriptions on recycled tombstones and from other structures ranging from 202/03 to 494. The three Djedars on Lakhdar are probably the oldest, of them again the largest, Djedar A , is also the oldest (4th century). The craftsmen's marks show that Djedar B was built a little later by the same group of craftsmen. Remains of a coffin from this building could be dated to 410 ± 50. The larger group, from which a find from Djedar F could be dated to the year 494, probably comes from the 6th or 7th century. Assignments to some of the few known Berber kings and emperors from this period have so far remained speculative.

Revolt of the Firmus (until 375)

In 370 or 372 to 375 the Mauritanian prince's son Firmus rebelled against whom the Roman governor of Africa had intrigued. Emperor Valentinian sent his general Flavius Theodosius , the father of the later Emperor Theodosius I, against him . He refused the submission offered by Firmus. After the military defeat, Firmus took his own life.

Vandal Empire (429 to 535)

In the course of the Great Migration , 429 maybe 50,000 (Prokop) or 80,000 Vandals and Alans under the leadership of Geiseric crossed from southern Spain to Africa. This corresponded to a force of about 10,000 to 15,000 men. Some Berber tribes supported them, as did supporters of Donatism, who hoped for protection from persecution by the Roman state church. In 435 Rome concluded a treaty with the Vandals, in which they received the two provinces of Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, as well as Numidia .

On October 19, 439 they conquered Carthage in breach of the treaty, and the fleet stationed there fell into their hands. 442 had to Valentinian III. acknowledge the facts created. With the help of the fleet, the Vandals managed to conquer Sardinia , Corsica and the Balearic Islands . They sacked Rome in 455.

The Vandals hung the Arianism to, a faith that in the First Council of Nicaea to heresy had been declared. Property of the Catholic Church was confiscated in its sphere of influence. The relatively small group of conquerors sealed themselves off from the provincial Roman subjects. The colonies, which were tied to the ground, are only likely to have changed the gentlemen; the imperial goods were probably simply converted into royal goods and served the ruling dynasty.

It was not until the murder of Emperor Valentinian in 455 that Geiseric's dynastic plans to marry his son Hunerich to Eudocia, a princess from an imperial family, were destroyed. During the attack on Rome he first resorted to Moors, i.e. Berbers. Eudocia was married to Hunerich. Now Cirta also became part of the Vandal Empire, but at the same time the Roman territories, which had to a certain extent become ownerless, became small states of their own, which opposed the Vandal Empire in changing coalitions. In Algeria this happened (from west to east) mainly around Altava , Ouarsenis, Hodna, in the Aurés, around Nememcha and Capsa . Many Berbers, in turn, were recruited for the naval ventures in the western Mediterranean.

After attempts by Rome to conquer the Vandal Empire, they plundered Sicily in 462, 463 and 465, with a defeat in 465. The victor Marcellinus succeeded in 466 in snatching Sardinia from the Vandals, but was sidelined. Another large-scale attempt, this time by Western and Eastern Roman troops to recapture Africa, failed in 468, and again in 470 - possibly by land via Tripolitania. In 472 the imperial crown went to Hunerich's brother-in-law Olybrius for a few months , so that Sicily fell to the Vandal Empire. In 474, Constantinople King Geiseric guaranteed the possession of Africa and the islands after the eventful battles over some of the western Greek islands and an attack on Nicopolis in Epirus .

After Geiserich's death in 477 he was succeeded by his eldest son Hunerich; he fought the Catholic Church more intensely and resorted to forced baptism. Apparently the Alans and Vandals opposed his succession, so that he tried to win the provincial Romans on his side. But the Catholic Church rejected a church that was independent of Rome and was forbidden from communicating with the Roman headquarters, so Hunerich turned against them. First, Hunerich struck down the inner-Germanic opposition, including the Patriarch of Carthage Iucundus . In two edicts , Hunerich closed all Catholic churches and called for a conversion to Arianism, similar to what earlier imperial edicts against heretics had done. He forced the bishops to take an oath on his son Hilderich as heir to the throne, but then made them colonists for violating the biblical ban on oaths. Those who refused to take the oath were exiled to Corsica and subjected to heavy physical labor.

484 Hunerich died suddenly towards the end of the year. His successor Thrasamund continued church politics, but allowed the establishment of monasteries. In 500 he married Amalafrida , the widowed sister of the Ostrogoth king Theodoric , who meanwhile ruled Italy. Nevertheless, the vandals lost their reputation, on the one hand because they did not support the Ostrogoths, on the other hand because they could not find any means against the Berbers, who were occupying Vandal territory piece by piece. In the meantime, this applied not only to Algeria, but also to the heartland in what is now Tunisia. The Albertini tablets document the unsafe situation in northwestern Tunisia around the Djebel Mrata as early as 493 to 496.

With Masuna , a "Rex Maurorum et Romanorum" appears in the sources for the first time, whose territory perhaps extended as far as the Aurès Mountains in southern Numidia. The title is an indication that the Moors in no way have to be understood as an ethnic term, but that numerous Romans can also be subsumed under it. When the Vandal king gave up the alliance with the Ostrogoth king, Theoderic planned a campaign of revenge, but he died in 526. At the same time, King Hilderic distanced himself from Arianism. The Moors, led by a certain Antalas, defeated a vandal army in eastern Tunisia. On June 15, 530 a conspiracy overturned in which a great-grandson of Geiseric named Gelimer played a central role, King Hilderic.

Soon the Vandals found it difficult to fight off attacks by the Moors. Masties made themselves completely independent and ruled the hinterland. He fought the Arians and possibly had himself proclaimed emperor. When Gelimer sat on the throne, Ostrom regarded him as a usurper . In 533 16,000 men landed in Africa under the leadership of the Eastern Roman general Belisarius . The realm of the Vandals went under after the Battle of Tricamarum .

Eastern Byzantium on the coastline (from 533), Berber empires in the hinterland

Eastern Roman military and civil administration, diocese, exarchate

Carthage became the seat of an Eastern Roman governor, a Praetorian prefect who was responsible for civil affairs and to whom six governors were subordinate. For the military sector, a Magister militum was appointed for imperial North Africa, to which four generals were subordinate. However, this system was flexible, so that occasionally there were two masters, or civil and military offices were in one hand. The Magister militum was also used as an honorary title without authority. The bishop of Carthage received the dignity of a metropolitan from the emperor in 535. There were a total of seven provinces, namely Proconsularis, Byzacium, Tripoli, Numidia, two Mauritania and Sardinia. There were also five Duces in Tripolitania (based in Leptis Magna ), Byzacium ( Capsa and Thelepte ), Numidia ( Constantina ), Mauritania ( Caesarea ) and the Dux of Sardinia . But here too a district could have two duces ; In addition , caution is advised with the term Dux , which appears frequently in the sources, but which initially no longer means a leader .

In 590, the Carthage Exarchate was created to pool military and civilian powers . The first exarch Gennadios (591-598) defeated the Moors. Around 600 Herakleios the Elder , the father of the emperor of the same name, became Exarch of Carthage, probably he was the successor of Gennadios. In 610 Herakleios overthrew the Eastern Roman usurper Phocas from Carthage by traveling with the Carthaginian fleet to Constantinople. When the Persians conquered large parts of the Eastern Roman Empire from 603, like Egypt in 619, Emperor Herakleios had plans to move the capital to Carthage. This did not happen, because he was able to defeat the Persians from 627 onwards.

Stotzas rebellion, support in Mauretania

When 536 parts of the garrison troops in Africa rebelled against the Eastern Roman general Solomon, they elected Stotza's soldiers as their leader. With an army that included around a thousand vandals and a few slaves in addition to the rebels , he besieged Carthage. According to Prokop , two thirds of the garrison troops had joined the rebels. When Belisarius landed back in Africa, Stotzas lifted the siege and withdrew to Membressa , but was defeated by Belisarius. Now Stotzas fled to Numidia, but was able to win another battle. General Germanus , a relative of the Emperor Justinian , was able to convince numerous rebels to defend, whereupon Stotzas sought battle and was defeated at Cellas Vatari, although behind his army there were some ten thousand Moors under Jabdas and Ortaias. But some tribes made alliances to Germanus even before the battle. Stotzas fled with a few faithful to Altava in Mauretania, where he married the daughter of a prince and is said to have assumed the title of king in 541. In 544 he invaded the province of Africa, gathered with rebels under Antalas, who had summoned him, but was killed by an arrow in a battle the next year, even if his army was victorious.

Striving for autonomy, Berber empires, Antalas and Cusina

This shows not only conflicts within the army and between military leaders, but also the fact that the Berber regions, above all Numidia, played an increasingly independent role. The Berber striving for autonomy had already intensified by the time of the Vandals; possibly further promoted by the religious policy of the Germanic peoples. At least some Berber groups adapted the Roman legitimation model and called themselves rex gentis Ucutamani (CIL. VIII. 8379). The Berber leader Masties ruled a territory in the Aurès. In order to legitimize his rule with the Roman provincials, after 476 - probably in 484 in connection with a rebellion of the Berbers against the Vandal King Hunerich mentioned by Prokop - he possibly accepted the imperial title and professed himself a Christian. An inscription attributes Masties 67 years as dux and 10 (according to another reading: 40) as “ imperator ” over “Romans and Moors”. The reign is thus either 484 to 494 or 476/477 to 516. Masties' “imperialism” has not been recognized by either Zeno or Anastasios I. A third inscription, this time from Altava , names a Masuna as king over "Romans and Moors", a title that perhaps goes back to a Roman, but possibly also to a Vandal rulership. The extent to which the Vandals also adopted those of the Germanic successor empires in addition to Roman models has long been researched, but the question of the extent to which the Berbers influenced the Vandal Empire, who apparently also saw themselves as legitimate successors and heirs of the Roman Empire, can hardly be answered.

Although the Vandal empire collapsed within a year of the eastern Roman attack, wars broke out that lasted more than twelve years; first within the army, then under the side of the Berbers. In 546, the dux Numidiae Guntarith and Johannes failed with another attempt at usurpation or vandalism. Belisar's successor Solomon had the fortresses expanded, and he managed to recapture long-lost areas, for example south of the Aurès. Many city walls were reinforced, such as those of Thugga and Vaga ( Béja ). The further hinterland of the provincial capital increasingly escaped the control of Constantinople. Berber rebellions contributed to this, such as 545-547 in Byzacena, the southern province in what is now Tunisia, then 563 in Numidia, the southern and western province of Numidia Zeugitana . Under Emperor Justin II a Byzantine army suffered a defeat, 587 insurgent Berbers stood before Carthage. The role of the Berber princes remained unclear, and people liked to talk about the popular character of the Berbers in order to negate this lack of clarity.

In 2003, Yves Modéran presented a fundamental study on the history of the Berbers. According to him, a distinction must be made between “internal” and “external” Berbers. The former were primarily the Romanized groups of the provinces of Byzacium and Numidia, i.e. eastern Algeria and Tunisia, the latter came from the east, i.e. from the area of today's state of Libya. While the "internal" Berbers integrated themselves into the Roman system of rule that spanned the entire Mediterranean in the late Roman period, they retained their tribal structure. Titles like praefectus gentis or princeps gentis were able to legitimize internal rule. In the time of the vandals, however, there was again increased tribalization. It was even belonging to a tribe that actually made the Berber what it was, while the Roman language, Christianity or title in no way diminished this membership. The “external” Berbers, on the other hand, were hostile to Roman culture and later to Christianity.

When the Vandals had been defeated, but still offered resistance, Berber envoys from Mauretania, Numidia and Byzacena appeared at the victorious general Belisarius and offered to place them under the imperial rule. But they demanded an investiture, probably an installation in their offices secured by Roman titles. The princes Antalas, Cusina and Iaudas, who played a central role in the rest of the story, are likely to have subordinated themselves accordingly. Antalas, born around 499, son of the prince of the Frexes named Gunefan, had already started fighting the vandals in 529. As a result of his victory over the Vandal Army in 530, the coup that had given Constantinople the legitimacy to intervene had come about.

When the Moors in the Byzacena rose against the east in 534/535, Antalas remained on the emperor's side. One of the leaders of the uprising was said Cusina, whose mother was a "Roman". He was therefore called Afrer , as the Roman-Berber population was called. The antagonism between Antalas and Cusina was decisive for the progress of the fighting.

After his defeat against Ostrom and Antalas, Cusina fled to Prince Iaudas in Numidia, who after Modéran was the worst known of the three Berber princes, but probably the most influential. He had risen in 535 in the eastern Algerian Aurès against Ostrom and now he took on Cusina. In 537 Solomon attacked him unsuccessfully, who was able to defeat him in 539. Iaudas did not surrender, however, but fled to Mauretania, what initially became of Cusina is not known. In 542 to 543 the region suffered the great plague , so that there was no further fighting. However, when Solomon 543 or 544 withdrew the promised subsidies from Antalas and even had his brother Guarizila executed, Antalas allied himself with the Berbers living in Libya on the Syrte, the Lawata . Under their priest-king Ierna, these “external” Berbers now moved west and sacked Roman territory - which had never happened before. Solomon was defeated against the Lawata and Antalas in a battle and was killed.

That could have ended the conflict between Solomon and Antalas. Antalas continued to regard himself as subordinate to the emperor, but since the death of his brother demanded that the nephew and successor of Solomon, who in his eyes was his brother's murderer, be recalled. With Constantinople not responding to this demand, the struggle continued and the Berbers captured Hadrumetum, today's Sousse .

In the following year 545, the Dux Numidiens, who were forging plans against Constantinople, contacted Antalas. In fact, Antalas as well as Cusina and Iaudas now supported the usurper Guntarith to march together on Carthage. The rivals Antalas and Cusina each conducted secret negotiations and tried to gain advantages. However, Guntarith heard about the negotiations of Cusina, but the negotiator knew nothing of his defection from the emperor. Guntarith had this negotiator named Areobindus murdered; at the same time Antalas was now aware of the betrayal of Cusina.

Guntarith sent the head of the Areobindus to Antalas, but he did not send the required troops and the money. Thereupon Antalas dropped Guntarith and submitted to the emperor. On the other hand, Cusina took Guntarith's side more openly. Roman troops under the Armenian Artabanes and troops under Cusina attacked Antalas together and defeated him, which could have ended the war between the two warring Berbers again. However, Artabanes had his own plans. After this victory he returned to Carthage, justified there why he had not pursued and destroyed Antalas further, and murdered Guntarith at a feast. He then left the province at his own request. He wanted to marry Praejecta, the widow of the murdered Areobindus and niece of Emperor Justinian, whom Guntarith had wanted to marry. The emperor appointed him the new magister militum of Africa. Although he was already married, Artabanes became engaged to Praejecta. A little later Artabanes was called back to Constantinople, and Johannes Troglita was his successor as army master . Artabanes' wife traveled to the capital and Empress Theodora urged Artabanes to stay with his wife. He was only able to divorce her after Theodora's death in 548, but Praejecta had since been remarried.

Johannes now led the fight against the Berbers, especially against Antalas, who had changed sides again, probably because this time too he had not received any wages for his work. Ostrom drew conclusions from this change of front insofar as his now ally Cusina received Roman troops - under his command. Antalas lost 546; Cusina and Iaudas fought on John's side. The Berbers from the Syrte, dispersed after the battle, rallied under Carcasan, who was also joined by the forces of Antalas, but in 548 they were finally defeated by John's army.

Again Antalas became a Roman ally, this time together with Cusina, even if their old enmity might have persisted. The latter even received the title of Exarch of the Moors . But the East Romans tried again to stop paying. Cusina was even murdered. But now his sons wandered the provinces, pillaging and murdering. Without honorary titles and payments to the increasingly autonomous Berber groups, peace on the extremely long border was hardly conceivable.

Arab expansion, Islamization

Foundation and first phase of expansion, split into Sunnis and Shiites

After the death of the founder of the religion, Mohammed, in 632, the Muslim coalition he founded threatened to break up. His successor Abū Bakr apparently recognized that the war of conquest was essential for their continued existence. Those who refused to pay the war tax were attacked accordingly, and the last resistance on the Arabian Peninsula collapsed in 634. From 634 to 640 Palestine and from 639 to 642 Egypt, together with Syria and Iraq, were conquered. In 636, the Muslims achieved decisive victories over the Eastern Roman and Sassanid empires at the Yarmuk in Syria and at Qadisiyya in Iraq, which had fought each other with the use of all their forces just a few years earlier.

According to Muslim tradition, both the Umayyads and the Prophet Mohammed descended from Abd Manaf ibn Qusayy , a member of the Quraish tribe. His son, Abd Shams ibn Abd Manaf , became the progenitor of the Umayyads. Abd Shams' son Umayya ibn Abd Shams was named after the Umayyads. After Mohammed had to flee to Medina with his followers in 622 and there was subsequent fighting against Mecca, members of the Umayyad family assumed leading positions on the side of the Meccans. In the later course of the fighting, Abū Sufyan ibn Harb was their leader at the head of Meccan politics. In the end, however, he had to surrender to Mohammed and converted to Islam himself shortly before the Muslim troops conquered Mecca in 630.

After the Prophet's death, Muawiya , a son of Abu Sufyan, took part in the campaigns against the Eastern Roman Empire and was rewarded in 639 with the post of governor of Syria. 644 with ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān even a member of the Umayyad clan was elected caliph. In contrast to the rest of his family, Uthman was one of the earliest supporters of Muhammad and had already been there when he escaped from Mecca in 622. When assigning influential posts, he favored his relatives to a large extent, so that an opposition to his rule soon formed. In 656 he was finally murdered in Medina. ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib , the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet, was elected to succeed him.

But Ali's election as caliph was not universally recognized by Muslims. As a supporter of the murdered Uthman, Muawiya was also proclaimed caliph in Damascus in 660 . This was the first time that the Muslim community (the Umma ) was divided. The result was the first Fitna , the first civil war of the Islamic empire. Although Muawiya was able to assert his rule after Ali's murder by the Kharijites in 661 and establish the Umayyad dynasty, he was still not recognized as the rightful ruler by the followers of Ali. The result was a schism between Sunnis and Shiites .

Second phase of expansion, Berber resistance, Islamization

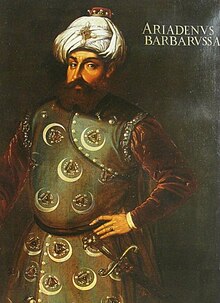

Under Muawiya I , the Arabs resumed their expansion , which had temporarily stalled due to internal disputes, from 661 onwards. From 664 new Arab attacks to the west followed. Africa was recaptured after the Eastern Roman exarch, together with the Berber prince Kusaila ibn Lemzem , had been crushed by Uqba ibn Nafi near Biskra in 683 . In 698 the general Hassan ibn an-Numan besieged Carthage with 40,000 men. Emperor Leontios sent a fleet under the later Emperor Tiberios II. They fought with varying success, but when they moved to Crete to pick up reinforcements, the besiegers succeeded in capturing and destroying the city.

Uqba's successor Abu al-Muhadschir Dinar was able to win over the "Berber king" Kusaylah in Tlemcen for Islam, who dominated the Awrāba clans in the Aurès as far as the area around the Moroccan Fez . When Uqba returned to office, he insisted on direct Arab rule and moved as far as the Atlantic. On the way back he was attacked on the orders of Kusaylah and with Eastern Roman support and killed in a battle. Against Kusaylah, Damascus dispatched Zuhayr ibn Qays al-Balawī , who recaptured Kairuan and defeated Kusaylah (before 688). A second Arab army under Ḥassān ibn al-Nuʿmān encountered heavy resistance from the Jawāra in the Aurès from 693 onwards. They were led by Damja, who was briefly called al-Kahina , the priestess, and defeated the Arabs in a battle in 698. In 701 the Arabs also defeated al-Kahina.

The Arab genealogists distinguish in these disputes between Barānis, to which Kusayla belonged and who were mostly sedentary, and Butr, to which the horsemen of the Zanāta belonged, and to which they also counted the people of the Kāhiina. The Barānis were heavily influenced by Roman culture and were often Christian; they divided into two groups, namely the Maṣmṣda of central and southern Morocco and the Ṣanhāğa. This nomadic group living in the desert, to which the settled Kutāma of eastern Algeria belonged, later produced the Almoravids . The Zanāta failed to establish a permanent empire and they were forced to move to Morocco. Many of them went to Spain. Numerous Jews also lived in the Maghreb, which contributed to the legend that the Confederation of Kāhina was Jewish. Christianity disappeared in the course of the following generations, but it can still be proven in the 11th century in Kairouan .

Kairuan later became the starting point for expeditions to the northern and western Maghreb. After stubborn resistance, most of the Berbers converted to Islam, mainly by joining the armed forces of the Arabs; culturally, however, they found no recognition, because the new masters treated them with as much contempt as the Greeks and Romans once had of their neighbors. They also adopted the Greek word barbaric for those who had not learned their language or who had not learned it enough in their eyes. Therefore the Imazighen (singular: Amazigh) are still called Berbers today . They were paid less in the army and their wives were sometimes enslaved, as with subjugated peoples. Only Umar II (717–720) forbade this practice and sent Muslim scholars to convert the Imazighen. In the Ribats Although religious schools have been set up, but there are numerous Berber joined the denomination of the Kharijites , which proclaimed the equality of all Muslims regardless of their race or social class. Resentment against the Umayyad rule increased. As early as 740, a first uprising of the Kharijites began near Tangier under the Berber Maysara . In 742 they controlled all of Algeria and threatened Kairuan.

The Warfajūma Berbers ruled the south in league with moderate Kharijites. They succeeded in conquering the north of Tunisia in 756. But another moderate Kharijite group, the Ibāḍiyyah from Tripolitania, proclaimed an imam who saw himself on the same level as the caliph and conquered Tunisia in 758. At Tawurga, in 761 these Ibadites, most of whom were Berbers, were defeated by the Arab Muslims. Their Imam Abū l-Chattāb al-Maʿāfirī was killed in the battle, as were 14,000 of his followers. Although the Abbasids succeeded in conquering large parts of the rebellious territory, they were only able to assert themselves in Tripolitania, Tunisia and Eastern Algeria. In addition, the reign that was painstakingly restored was very fragile. Ibrāhīm ibn al-Aghlab, who commanded the army in eastern Algeria and founded the Aghlabid dynasty, gradually made the country independent, but still formally recognized the rule of the Abbasids.

Aghlabids in the east (800 to 909), Kotama (approx. 900 to 911)

First Islamic empire founded in the eastern Maghreb

In the year 800 the Abasid caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd handed over his power over Ifrīqiya to the Emir Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab and gave him the right to inherit his function. With this the Aghlabid dynasty was founded, which ruled eastern Algeria, Tunisia and Tripolitania. Around 896 they moved their court to Tunis .

Most of the land belonged to large Arab landowners, while the ethnically mixed cities were burdened with high taxes. They and the Berbers invoked Islamic norms to protest against Arab dominance. Two of the four Sunni schools, the Hanafis and the Malikites , ruled the country; the former came to Algeria with the Abbasids, but most of them were attached to the latter. They appeared from the 820s as the people's defenders against the claims of the state and made high moral demands on a just government. In order to involve them more closely, many of their leaders were employed as kadis .

Tribal groups of the Berbers, dominance of the Kotama (until 911)

The large tribal groups of the Berbers in the Maghreb were the Zanāta , the Masmuda and the Ṣanhāǧa . While the Zanata lived in Morocco, the Ṣanhāǧa tribes settled in the Middle Atlas , but also expanded much further south. A part of the Ṣanhāǧa settled in eastern Algeria (Kutāmaberber) and formed an important pillar for the rise of the Fatimids . In contrast, the Moroccan Zanāta allied against the Fatimids with the Caliphate of Cordoba . Remaining groups of the Masmuda are the Haha around Algiers.

Already in Byzantine times, Berber associations had come together to form larger domains; their leaders were called kings. Above all, the Kotama or Kutāma managed to bind the neighboring tribes to themselves. In Algeria the Berber Kabyls are descendants of the Kutāma. The Kutama conquered Mila in 902 , Sétif in 905, Tobna and Bélezma followed in 905, and in 909 their leader Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Shīʿī (893–911) even managed to conquer Kairouan and Raqqada . In 893 he founded an extremely successful Shiite cell among the Kotama, the dār al-hiğra on Mount Ikğān near Mila (the name 'al-hiğra' was an allusion to the Hijra of Muhammad). Finally they reached far to the west in the direction of Sidschilmasa and freed their leader Abdallah al-Mahdi , who had been imprisoned there and who had passed himself off as a merchant since his escape from Syria, who would later become the first caliph of the Fatimid dynasty.

Both leaders, however, strove for secular rule, while the Berber leader only intended spiritual leadership for his ally. In an upheaval on February 18, 911, the Berber rule was overturned and its leaders murdered. As a result, Arabization intensified. The new rulers took over large parts of the Aghlabid ruling apparatus.

Fatimids (909 to about 1016/1045)

In December 909, Abdallah al-Mahdi had proclaimed himself caliph. He regarded the Sunni Umayyads on the Iberian Peninsula and the Sunni Abbasids as usurpers . He himself was a representative of the Ismailis , a radical wing of the Shiites , also known as the Shiite Seven. Since the middle of the 9th century, the Ismailis initially operated from their center of Salamiyya in northern Syria. They sent daʿis , missionaries, who made contact with opposition groups in the Abbasid Empire. From 901 they also appeared in the Kutama of Eastern Algeria. These eliminated the power of the Aghlabids. The Fatimid state now spread its influence over all of North Africa by bringing the caravanserais and thus the trade routes with Trans-Saharan Africa under its control. In 911 they again eliminated the Berbers, especially the Kutama, as rivals for supremacy in Ifriqiya. As a symbol of the new rule, the capital was moved to al-Mahdiya on the east coast of Tunisia, but the dynasty failed with the introduction of Sharia law .

The conquest of the western Maghreb began in 917. While it succeeded in taking Fez , but the Berbers of the West resisted successfully. In return, the Umayyads in Spain conquered Melilla and Ceuta in 927 and 931 . In contrast, the Takalata branch of the Ṣanhāǧa Confederation, to which the Kutama belonged, stood on the side of the Fatimids. But there could only be talk of real rule in Ifriqiya.

Ismail al-Mansur (946–953) succeeded the second Fatimid ruler, who died in 946 . Using the Berber Zirids (972-1149), who belonged to the Ṣanhāǧa, he could Banu Ifran subject in western Algeria and Morocco: The last great revolt of Kharijite Banu-Ifran tribe under Abu Yazid was put down after four years in the year 947 . The Banu Ifran had conquered large parts of the empire, but their coalition broke up during the siege of al-Mahdiya. Then the third Fatimid caliph took the nickname "al-Mansur". The Banu Ifran had founded a " caliphate " under Abu Qurra near Tlemcen between 765 and 786 , but had come under the rule of the Moroccan Magrawa . They were defeated by the Fatimids when they tried to form an alliance with Cordoba and were eventually driven to Morocco.

The fourth Fatimid caliph was Abu Tamim al-Muizz (953-975). From 955 he fought the Berbers and the Iberian Umayyads in the west. The conquest of Northwest Africa was completed in 968, after an armistice had been agreed with Byzantium in 967. So, relieved by internal crises in Egypt and on the Arabian Peninsula, the Fatimids succeeded in conquering the Egyptian Ichschidid Empire and Abbasid territories from 969 onwards. After temporary conquests in Syria, the Fatimids moved their residence to the newly founded Cairo . In 972, three years after the region was completely conquered, the Fatimid dynasty moved its base to the east. The focus of the vastly grown empire was now Egypt.

Escape of the Kharijites to central Algeria

Since the 9th century, Kharijites fled to the sparsely populated M'zab , especially Ibadites . These go back to ʿAbdallāh ibn Ibād (8th century). After their capital in Tahert was burned down in 909, they moved first to Sedrata and then to M'zab. There they expanded the oases with the help of irrigation systems and planted palm groves. Like many other groups, they are not recognized as Muslims by the rest of the Islamic world.

The five citadel-like towns or Ksour El Atteuf, Bou Noura, Beni Isguen, Mélika and today's capital Ghardaia were founded. Each is surrounded by a wall. Each city of the Mozabites represented a theocratic republic, with a council of twelve religious notables responsible for the administration of justice, while a council of lay people directed the administration. The mosques also served as arsenals and granaries as well as independent fortifications. The houses were built in several circles concentrically around the mosque and consist of one room of uniform size. El Atteuf is the oldest establishment. It was built from 1012 onwards. The other cities were built until around 1350.

The Ibadites of Algeria are called Mozabites . As head they only recognize an elected caliph who is recognized by God as the best Muslim. One of the first scientific papers was written in 1893.

Zirids (972 to 1149) and Ḥammādids, Banu Hillal, Disappearance of Christianity

Capital Cairo, Viceroyalty of the Zirids, Hammadids

To secure rule in the west, Caliph Abu Tamim al-Muizz placed rule over Ifriqiya in the hands of Buluggin ibn Ziri , who founded the Zirid dynasty. He was the son of Ziri ibn Manad , the main Fatimid ally in Algeria and namesake of the dynasty. Algiers was founded under its founder, Buluggin ibn Ziri († 984); he fought the Zanata tribes in the west. More precisely, Buluggin's capital was built between 935/936 and 978 in Aschir in the south of Algiers. In addition, Liliana and Médéa (Lamdiyya) became bases of his power.