History of Mauritius

The history of Mauritius encompasses the history of the modern state of Mauritius as well as the previous European colonization of the African island, which is located east of Madagascar . After the Portuguese only used the island as a base, but not as a colony , the settlement of Mauritius did not begin until 1598 when the Netherlands took possession of the island, who named the island after Prince Moritz of Orange (Latin: Mauritius). When the Dutch left the island in 1710, it was occupied by the French , but the British conquered the island in 1810 . Mauritius achieved its independence on March 12, 1968 and became a republic on March 12, 1992 after the introduction of a new constitution.

Pre-colonial period

The Mascarene archipelago , which includes Mauritius, Rodrigues and Réunion , arose around eight million years ago as a result of volcanic activity in the southwestern part of the Indian Ocean .

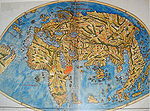

It is not known whether the island was already known to the Phoenicians and Malays . According to stories, the latter are said to have discovered the island on their travels from Madagascar to Indonesia . However, there is no evidence of this. The island is shown on some old Arabic nautical charts and was known to the Arabs as early as the 10th century. Arab sailors named the island Dina Harobi , which means something like "deserted island". Later it is said to have become Dina Robin , which means "Silver Island". The Arabs did not settle on the island, however, as they were mainly traders and only used the island for recreation, food and drinking water. For this reason, no traces or remains of them can be found.

Portuguese period (1507–1598)

It is not known whether Vasco da Gama , who was the first European to discover the sea route to India in 1498 , was also the first to discover the Mascarene Mountains. In any case, they are marked on the Portuguese Cantino map from 1502. However, this can also be due to the fact that the position of the islands was taken from an Arabic map.

The island was officially discovered by Europeans in 1507 (other sources mention 1505 or 1510) by the Portuguese Diego Fernandez Pereira. He named the island Ilha do Cerne , which means something like swan island . Some sources say this is an allusion to the dodos . Other sources say that Cerne was "the name of the ship from Pareira". Pedro Mascarenhas sighted the archipelago about ten years later. After him, the three islands were called Islas Mascarenhas on maps since 1620 . The archipelago is still called Mascarene after him.

However, the Portuguese did not see the island as a useful port of call, as it is relatively isolated and at that time offered no commercial goods. The main Portuguese base in Africa was Mozambique ; therefore, the Portuguese sailing ships used the Mozambique Channel to get to India. In addition, the Comoros further north on the route to South and East Asia are more conveniently located and were therefore mainly used as a port of call. For this reason, the Mascarene were not used by the Portuguese as a permanently occupied colony. They only landed there occasionally to stock up on fresh water and food by sea through the Indian Ocean. To do this, they brought cattle , pigs and monkeys to the island in addition to the native species .

Dutch period (1598-1710)

Dutch sailing ships (1598–1637)

In 1598 a Dutch expedition consisting of eight ships started from Texel ( Netherlands ) under the command of Admiral Jacques Cornelius van Neck and Wybrandt van Warwyck towards the Indian subcontinent . The eight ships ran into stormy seas after passing the Cape of Good Hope and were separated. Three ships found their way to the northeast coast of Madagascar, while the remaining five embarked on a more southeastern route. On September 17, 1598, the ships under the command of Admiral van Warwyck came within sight of the island. On September 20, they landed in a sheltered bay and named it "Port de Warwyck" (today's name is Grand Port ) in the southeast of the island. They decided to name the island "Prins Maurits van Nassaueiland", based on Prince Moritz of Orange ( Netherlandish Maurits, Latin Mauritius) from the House of Nassau , the governor of Holland . From this time only the name Mauritius remains. On October 2, the ships left for Bantam .

Since then, the "Port de Warwyck" has often been used as a port of call for stopovers after long months at sea. In 1606 an expedition landed where Port Louis is today , in the northwest of the island. The expedition, consisting of eleven ships and 1,357 men under the command of Admiral Corneille, landed on a beach which they called "Rade des Tortues" (port of the turtles) because of the many tortoises there.

Since that time, Dutch ships have regularly chosen the “Rade des Tortues” as a port of call on the route to India. After the shipwreck and the associated death of Governor Pieter Both , who was on the way back from the Dutch East Indies with four loaded ships , the rumor spread from 1615 that the route via Mauritius was cursed. As a result, Dutch sailors tried to avoid this route as much as possible and instead to take the route via Madagascar.

At the same time, the English and the Danes advanced further and further into the Indian Ocean. Those of them who landed on the island felled the ebony trees , which were then in abundance, and took the precious bark with them.

Dutch colonization (1638-1710)

Dutch colonization began in 1638 and ended in 1710 with the exception of a brief interruption between 1658 and 1666. The island was not continuously settled for the first 40 years since the discovery by the Dutch, but in 1638 Cornelius Gooyer established the first permanent settlement on Mauritius as a garrison of 25 inhabitants, named Fort Frederik Hendrik. He also became the island's first governor. France took possession of the neighboring islands of Rodrigues and Réunion in the same year. In 1639 another 30 settlers came to strengthen the Dutch colony. Gooyer was hired to expand the island's trading potential, but was eventually dismissed for failure. He was succeeded by Adriann van der Stel , who began to export ebony bark . For this purpose Van der Stel bought 105 Malagasy slaves. Within the first week 60 slaves managed to escape into the woods and only about 20 of them were eventually brought back.

In 1644, the residents had to overcome some strokes of fate such as cyclones , poor harvests and delays in supply ships. During these months the colonists lived only from fishing and hunting. Nonetheless, van der Stel secured the sending of 95 more slaves from Madagascar before he was transferred to Sri Lanka . His successor was Jacob van der Meersh. In 1645 he had 108 more slaves brought from Madagascar. Van der Meersh left Mauritius in 1648 and was replaced by Reinier Por.

In the years 1652 to 1657 the residents had to survive further hardships. The population at that time was about 100 settlers. In 1657 the population finally asked to be evacuated from the island due to the ongoing pressures. On July 16, 1658, almost all of the residents left the island. The only exceptions were a boy and two slaves who had found shelter in the forest. In this way, the first attempt by the Dutch to colonize the island failed.

A second attempt was made in 1664. However, the men selected for this left the sick commandant van Niewland to his fate, whereupon he died.

From 1666 to 1669 Dirk Jansz Smiet built a new colony on Grand Harbor, with the main task of logging and exporting ebony. When Dirk Jansz Smiet left the island, he was replaced by George Frederik Wreeden . He drowned in 1672 along with five other colonists on a reconnaissance expedition. Hubert Hugo was his successor . He was a man of vision who wanted to turn the island into an agricultural colony. His vision was not supported by his superiors and he was therefore not able to fully implement his ideas. Isaac Johannes Lamotius became the new governor when Hugo left the island in 1677. Lamotius ruled until 1692 when he was transferred to Batavia (now Jakarta). So in 1692 Roelof Deodati was appointed the new governor. Although he tried to develop the island further, he repeatedly had to overcome major problems. These were - as in the 1650s - cyclones , droughts , pests , but also cattle epidemics. Deodati finally gave up and was replaced by Abraham Momber van de Velde . This fared no better and he was after all the last Dutch governor on Mauritius. In 1710 the Dutch left the island for good. Mauritius was almost completely cleared and the animal populations (such as that of the dodos) exterminated or severely decimated.

The legacy of the Dutch

A holdover from the former rule of the Dutch is the naming of the island and many regions across the island. For example, the second highest mountain in Mauritius is named after Pieter Both. The Dutch also imported sugar cane from Java and cultivated it intensively on plantations. Over time, the sugar industry developed into one of the most important economic goods on the island and the sugar cane plantations determine the appearance of the country to this day. The settlers introduced new animal species which, however, competed with the existing species. Pests were also brought to the island with the animals. In addition to these two factors, the colonists' hunt for food resulted in the extermination or decimation of the dodo and giant tortoise populations . Large parts of the forests were also destroyed and cut down to obtain ebony and to gain space for growing sugar cane.

Piracy Period (1710-1715)

When the Dutch left the island of Mauritius for South Africa around 1710, pirates settled on Mauritius. Pirates began to spread in the Indian Ocean as early as the middle of the 17th century, as it was very lucrative for them there. Remote from the large bases of the European trading powers England and France, they were able to establish themselves undisturbed on Mauritius and the other islands in the Indian Ocean and at the same time had the opportunity to take the large trading ships, which were mostly fully loaded on their way from East Asia to Europe sailed along the islands not far to rob. They operated more and more brazenly and did considerable damage to merchant shipping. In order to stop the attacks, the trading power France intervened and fought against the now well-organized piracy, which could not withstand the offensive.

French period (1715-1810)

Abandoned by the Dutch, the country became a French colony in 1715 when Guillaume Dufresne D'Arsel used Mauritius as a port of call on the route to India, claimed the island for France and found the island in Île de France ( French : "Island of France") ) renamed. But it wasn't until 1721 that the French began their settlement. At that time there were only 15 colonists and quite a few slaves living in Mauritius. Mahé de Labourdonnais was governor of Île de France from 1734 to 1746 and founded Port Louis in 1735 as a naval base and shipbuilding center, where he established the governor's seat. He was the first to effectively develop Île de France . Many new buildings were built under him, some of which still stand today, including the Government House , the Chateau de Mon Plaisir in Pamplemousses and the Line Barracks . Labourdonnais promoted the development of infrastructure and agriculture. He had sugar cane plantations built and cultivated by slaves from East Africa and Madagascar, which still characterize the landscape of the island today. The first two sugar refineries opened in 1744. The subsequent governors were not able to continue the upswing of Mauritius.

As a result of the Seven Years' War , the French East India Company , which until then was the owner of the island and also administered it, went bankrupt. From 1767 to 1810 the island was a French crown colony with the exception of a brief period during the French Revolution . The first governor after the island passed to the French crown was Pierre Poivre , who managed to build on the successful time under Labourdonnais. He had the infrastructure and buildings renewed, expanded and intensified the cultivation of spices in order to secure new trade goods and thereby also break the monopoly of the Dutch in the spice trade that prevailed at the time. Under him, the Pamplemousses Botanical Gardens (today's name is Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden ) were expanded significantly and became one of the most beautiful botanical gardens in the world. In 1776, according to the census, there were already 33,536 people on the island, most of them (around 85%) slaves, while only a good 6,000 people were of European descent.

When slavery was abolished in the course of the French Revolution from 1794 to 1803, the colonists broke with France for that period to lessen the impact on the island's agriculture. At the same time, the Mauritians tried to become more independent from France and therefore began to trade more with other countries. In particular, trade with neutral countries such as America and Denmark was expanded. A total of around 200 shiploads were transported to America alone in 1805 and 1806. As the Île de France continued to grow economically, the British became aware of the island, especially since they had already advanced as far as the Seychelles in 1794 and took them into their possession. During the Napoleonic Wars , the island became a base for French corsairs who ambushed and robbed British merchant ships in order to weaken the British in the war. They did this with the permission of the French government, which issued them a letter of misery. The Île de France thus offered the corsairs a safe haven. The English wanted to stop these raids by offering high bounties on the corsairs . However, this did not bring the hoped-for success and therefore the raids continued until 1810, when a powerful British fleet was sent to the Île de France .

British period (1810-1968)

Initially, the French fleet was able to emerge victorious in the battle in the Grand Port under the commodore Pierre Bouvet on August 19 and 20, 1810. Since this was the only naval victory of the French over the British, Napoleon even had it depicted on the triumphal arch in Paris . The British landed with 60 ships and a total of 1000 men in the north at Cap Malheureux . They had discovered a gap in the coral reef that surrounds the entire island and were able to cross over to the island with the boats. Since this went unnoticed and the French did not expect a land attack from the northeast, the British were able to advance quickly to the capital, which was only 29 kilometers away from the landing site. The governor Dacaen had expected that the British would attack the capital from the sea and had therefore dropped his fleet in Port Louis. The French capitulated on December 3, 1810, as the British were clearly superior to the 4,000 French. In the Treaty of Paris of 1814, the island went to Great Britain along with Rodrigues and the Seychelles and was renamed from "Île de France" to Mauritius. In the treaty, the British pledged that the language, customs, laws and traditions of the residents would be respected. Such generous treatment was already assured in the surrender conditions of 1810. This is probably due to the fact that Mauritius was too small and economically too insignificant and the strategically favorable location alone was enough for the British to profit from the war.

From 1814 Mauritius was a British crown colony and thus belonged to the British Empire . The British occupiers had little influence on the events and conditions on the island. Many French institutions were therefore preserved, for example the French language , which was then more widely spoken than English , and the Napoleonic Code civil .

The British administration began under Governor Robert Farquhar and was marked by social and economic changes. The sugar cane cultivation started by the Dutch and supported by the French was expanded until a monoculture emerged . At the end of the 19th century the production of sugar cane was 100,000 tons, and the cultivation area of sugar cane accounted for up to 90 percent of the arable land on the island. As a result, many more sugar factories were built, so that at times there were up to 300 of them on the island. The increasing economic output required an improved infrastructure. In 1864 the first railway line from Port Louis to Flacq was opened. Around 200 kilometers of track had been laid by 1904. The port of Port Louis was modernized and charities were established. The postal system was also improved with the construction of more post offices. In 1847 the first postage stamps , known as the Red and Blue Mauritius , were printed . This made Mauritius the fifth country in the world to issue postage stamps.

After the British colonial power had banned slavery in 1835, the majority of the freed slaves, who at the time of the French occupation came mainly from Madagascar and other African countries, were not ready to work for the colonial masters in the fields. The farmers received two million pounds sterling in compensation for the abolition of slavery . However, since the expanding sugar industry needed a large workforce, contract workers from India , also known as coolies , were recruited . In the middle of the 19th century, for example, a mass immigration of Indian workers, Hindus and Muslims began, who now took over the work on the sugar cane plantations. Most of them were housed in the Aapravasi Ghat , an immigration depot that still stands today. All immigrants were actually given a five-year fixed-term employment contract, but most of them could not afford to return to their homeland after the contract expired.

At that time the Franco-Mauritians owned almost all of the large sugar cane plantations, actively traded and controlled banking. The Indo-Mauritian proportion of the population rose steadily due to immigration, and thus their political power also grew. In 1865 the proportion of the population of Indian origin was around 50 percent. Because there were more and more immigrants, unemployment rose and from 1871 onwards a ban on immigration was imposed for so-called “contract workers” because Indians working on the plantations had meanwhile reached 60 percent of the population. Conflicts between the Indian community (mostly the working class) and the Franco-Mauritian upper class grew significantly in the 1920s. Violent attacks broke out, causing several deaths among Indian immigrants. To protect workers' interests, Dr. Maurice Cure in 1936 with the Mauritius Labor Party (MLP), the first political party in Mauritius. A year later, Emmanuel Anquetil took over the party leadership and tried to win over the port workers. After his death in December 1946, Guy Rozemond directed the fortunes of this party.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 heralded the decline in Mauritius' importance as a port of call for ships circumnavigating the Cape of Good Hope on the route from East Asia to Europe. Because of the monoculture, the economy on the island was particularly dependent on the development of the world market price for sugar cane. Since more and more sugar cane was grown in the Caribbean and sugar beet began to be grown in Europe, the price of sugar cane fell significantly and, at the end of the 19th century, there was a crisis in the sugar cane industry in Mauritius and thus the entire economy. This led to the emigration of a large part of the population. Between 1937 and 1943 there were also a few strikes in the sugar cane industry due to the changed political situation.

Mauritius was not spared from epidemics and environmental disasters either. Between 1866 and 1868 there was a malaria epidemic that killed around 50,000 Mauritians. Shortly before the turn of the century, a cholera epidemic broke out, the cyclone in Mauritius in 1892 destroyed parts of the island and a major fire destroyed Port Louis.

At the end of the 19th century, attempts were increasingly made to halt the decline through reforms. In 1885, voting rights for members of the oligarchy were enshrined in the constitution. By restricting the number of eligible voters, only two percent of the population voted in 1909. For this reason, the Franco-Mauritians in particular controlled political affairs. Because of the economic crisis, attempts were made to become more independent from sugar cane, but this did not succeed. This was also due to the fact that the Franco-Mauritians owned most of the sugar cane plantations. Mauritius remained almost at the level of the late 19th century until the Second World War . During the war, the British built a military airfield at Plaisance and used it as a base in the Indian Ocean. From 1946 it was converted to a civil airport.

When the Imperial Japanese Army conquered Burma in the Second World War , an important Mauritian rice supplier was lost and there was a food shortage, so that food had to be rationed. Another problem was that prices had doubled since the turn of the century, while average wages remained unchanged. Since the lower class in particular suffered from this and the Labor Party was unable to achieve any political improvement, protests and political movements became more frequent. The workers formed themselves into trade unions and other interest groups to give their demands weight. Due to mounting pressure, the governor, the colonial bureau and the political parties met for negotiations that resulted in a new constitution.

The way to independence

The new electoral law, which came into effect in 1947, granted the right to vote to every Mauritian who could read and write and were over the age of 21. In the British island colony of Mauritius, political representation had previously been limited to the elite. This introduced women's suffrage . All of this changed the previous balance of power because now significantly more Indians were eligible to vote. In the 1947 elections for the newly founded Legislative Assembly, a majority of Indo-Mauritians were elected accordingly. They were able to provide 11 of the 19 MPs. The Labor Party, which was led by Guy Rozemont and was the only politically active party up to that time, only got 4 seats. It was the first time that the Franco-Mauritians had been ousted from power. A new constitution in 1959 introduced universal suffrage for adults. Since the elections of 1959, a coalition of the Labor Party and the Muslim Committee of Action (CAM), which was formed from representatives of Muslims and Hindus, got a majority and began to campaign for independence . The independence movement was intensified in 1961 when the British government promised extensive self-determination and even independence from Mauritius.

In 1965 a conference was held in London to work towards the island's independence. In the 1967 elections, the main concern was whether the population really wanted the country's independence, since the election indirectly also made the decision about independence. The coalition of the Labor Party, CAM and the Independent Forward Bloc (IFB), a traditionalist Hindu party, got a majority in the Legislative Assembly against the Franco-Mauritian opposition, which was made up only of the Mauritian Social Democratic Party (PMSD) under Jules Koenig and Gaetan Duvals existed. Thus, the parties that spoke out in favor of independence were able to win by a narrow margin. So nothing stood in the way of independence.

independence

1968-1992

After 150 years of British rule, Mauritius became independent on March 12, 1968 and thus lost its membership of the British Empire , but instead joined the Commonwealth . The proclamation took place on the Champ de Mars in Port Louis. The first prime minister became the leader of the Labor Party, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam , who ruled Mauritius for the first 14 years of its independence. The women's suffrage was confirmed.

A condition for independence was that Mauritius had to cede the Chagos Archipelago , which had been administered from Port Louis since the French time, to Great Britain, and the latter leased the archipelago to the USA. In the years that followed, the inhabitants of the archipelago were gradually forcibly relocated to Mauritius and the Seychelles, while military and intelligence structures were established there. This led to some resentments between Mauritius and the USA, which still persist today.

Economically, people began to make themselves more independent of sugar cane. Even if sugar still made up a large part of exports, it was possible to establish another successful economic sector with the establishment of a textile industry . In the meantime, the establishment of a free trade area and a rising sugar price brought an economic recovery. This did not last long, however, as cyclones, a renewed drop in the price of sugar and the high population growth caused problems. In the end, the free trade zone did not bring the desired success either. The number of unemployed rose to 20%, inflation was enormous and the economy stagnated. The rationalization of the handling of transport ships in the port also resulted in almost 2,000 more layoffs. This also made the industry less dependent on strikes.

The economy picked up again in the 1980s. The EU guaranteed a quota of 507,000 tonnes of sugar (3/4 of the annual production) at an above-average price. The share of industry in GDP rose to 15% by 1987, while at the same time the share of sugar cane fell from 23% (1968) to 13.3% (1987). In the same year, the number of employees in textile production also exceeded the workforce in sugar production. An increasingly strong tourism industry also guaranteed continuous economic growth. In the mid-1990s unemployment could be reduced to 1.6%.

In 1982 the alliance of the Mouvement Militant Mauricien (MMM), founded in 1970, and the Parti Socialiste Mauricien (PSM) got an overwhelming majority. Anerood Jugnauth , chairman of the MMM, became prime minister and Harish Boodhoo became his deputy. Berenger, who was finance minister at the time, wanted to meet the demands of the International Monetary Fund , which would have resulted in privatizations and an assurance that part of the sugar cane would be purchased. In return, some of the officials would have had to be fired and food prices would have risen. Because of the resistance of the PSM, the coalition broke up in 1983 and Anerood Jugnauth then founded the Mouvement Socialiste Mauricien (MSM), which then took over government after a narrow election victory as the coalition government. A first attempt to make Mauritius a republic under Paul Bérenger as president in 1990 failed due to the approval of the opposition.

After Seewoosagur's death, his son Navin Ramgoolam took over the management of the MLP. In the 1991 elections, the MLP and the PMSD were subject to the MSM under Jugnauth, who was thus re-elected.

| Prime Minister of Mauritius | |

|---|---|

| Seewoosagur Ramgoolam | 1968-1982 |

| Anerood Jugnauth | 1982-1995 |

| Navin Ramgoolam | 1995-2000 |

| Anerood Jugnauth | 2000-2003 |

| Paul Berenger | 2003-2005 |

| Navin Ramgoolam | 2005-2014 |

| Anerood Jugnauth | since 2014 |

Republic of Mauritius

On March 12, 1992, Mauritius became an independent Parliamentary Republic in the Commonwealth after a new constitution was introduced. The role of head of state was formally passed from Queen Elizabeth II to the previous Governor General Veerasamy Ringadoo , who was replaced by the new President Cassam Uteem in June 1992 .

After some political scandals connected with corruption and drug trafficking , the MSM was pushed into the opposition in the 1995 elections, and the MMM and the MLP were able to achieve a clear majority in parliament by winning a total of 60 of the 62 seats in the Legislative Assembly were able to. This made Navin Ramgoolam of MLP, the son of the first Mauritian Prime Minister, also Prime Minister. The coalition broke up again in 1997, when Bérenger and his MMM left the coalition, and cabinet reshuffles took place. In the next elections in 2000, Jugnauths MSM was able to achieve a majority together with Bérengers MMM, and the former again became Prime Minister. He gave up this office after three years and instead took the office of president. For the remaining term of office, Paul Bérenger took over the post of Prime Minister.

Navin Ramgoolam has been Prime Minister again since the July 2005 elections after the MLP won the elections in the so-called Social Alliance with the MSM. Sir Anerood Jugnauth remained president.

See also

- Postal history and postage stamps of Mauritius

- History of the reunions

- Story of Rodrigues

- History of africa

literature

- Ulrich Fleischmann, Eberhard B. Freise: Mauritius . Bucher's Fernreisen, Munich and Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-7658-0713-3

- Kay Maeritz: Mauritius and Réunion. Bruckmann's country portraits, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7654-3044-7

- Alain Proust, Alain Mountain: Mauritius. Fascination Far Lands, New Holland 1995, ISBN 90-5390-658-4

- Ulrich Quack: Mauritius Réunion. Iwanowski's travel book publisher, Dormagen 1998, ISBN 3-923975-20-1

- Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-86099-120-5 .

Web links

- Detailed history at geocities.com ( Memento from September 22, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Timeline of history from the ADAC travel guide ( memento from October 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Encyclopedia Mauritiana, The Mauritian Encyclopedia (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Alain Proust, Alain Mountain: Mauritius. Fascination with distant countries . New Holland 1995, p. 15

- ^ A b c Ulrich Fleischmann, Eberhard B. Freise: Mauritius. Bucher's long-distance travel. Munich and Berlin 1991, p. 8

- ^ Alain Proust, Alain Mountain: Mauritius. Fascination with distant countries . New Holland 1995, p. 16

- ↑ Auguste Toussaint, Histoire des îles Mascareignes . Paris 1972, p. 24

- ↑ Dr A. Satteeanund Peerthum: Resistance Against Slavery. In: Slavery in the South West Indian Ocean , MGI, 1989 p. 25

- ↑ Albert Pitot: T'Eyland Mauritius, Esquisses Historiques (1598 to 1710). 1905, p. 116

- ^ Alain Proust, Alain Mountain: Mauritius. Fascination with distant countries. New Holland 1995, p. 17

- ↑ Kay Maeritz: Mauritius with Réunion. Bruckmann's country portraits, Munich 1997, p. 41

- ^ A b Alain Proust, Alain Mountain: Mauritius. Fascination with distant countries. New Holland 1995, p. 18

- ^ Ulrich Quack: Mauritius Réunion. Iwanowskis Reisebuchverlag, Dormagen 1998, p. 23

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 39

- ^ A b Alain Proust, Alain Mountain: Mauritius. Fascination with distant countries. New Holland 1995, p. 19

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 38

- ↑ a b Walter Schicho: Handbuch Afrika. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 42.

- ↑ a b June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 7.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved October 5, 2018 .

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 43.

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 45

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 46

- ↑ Dominique Dordain, Phillippe Hein: Économie ouverte et industrialization: le cas de l'île maurice , 1989, p. 17

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 47

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 48

- ↑ Kay Maeritz: Mauritius and Réunion. Bruckmann's country portraits , Munich 1997, p. 136

- ^ Walter Schicho: Handbook Africa. In three volumes. Volume 1: Central Africa, Southern Africa and the States in the Indian Ocean. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, p. 49