History of Malawi

The history of Malawi encompasses developments in the territory of the Republic of Malawi from prehistory to the present.

History until 1859

In Karonga the location is the - according to the mandibular fragment LD 350-1 - second oldest to the genus Homo provided fossil , which so far from Palaeoanthropologists was discovered. The 2.4 million year old dentate lower jaw was recovered as part of the Hominid Corridor Project and given archive number UR 501 ; it was classified as Homo rudolfensis by its discoverers, Timothy Bromage and Friedemann Schrenk . In Karonga, on the basis of an initiative by Schrenk, with the support of the German Society for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) and the Uraha Foundation, a culture and museum center was set up which, among other things, is to house finds from pre-human beings.

The first known inhabitants of the region from the species of modern humans (Homo sapiens) were the San , who came to what is now Malawi around 3500 years ago. The rock carvings that still exist today in the caves of Chencherere and Mphunzi south of the city of Lilongwe bear witness to their presence .

The Nkope culture at Lake Malawi , the Longwe culture at Mulanje and near Nsanje are also important. Bantu peoples immigrated to Malawi by 1000 AD .

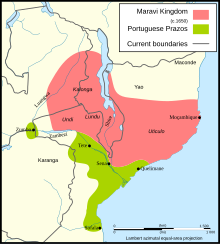

Malawi derives its name from the kingdom of the Maravi , who ruled large parts of Malawi and northern Mozambique between 1500 and 1700 . The first Europeans in Malawi were Portuguese traders from the coastal cities of Mozambique. Known by name is Caspar Bocarro , the precious metals from the mines at Zumbo exchanged on the Zambezi against European goods. A few Jesuits also came to the area, but did not establish any communities or settlements. However, they brought with them the legend of a huge lake in the north of the area. The Portuguese bought ivory, slaves, gold, and food, and sold European goods and corn seeds. A Portuguese delegation under F. de Lacerda found Lake Mweru , but not Lake Malawi , if they were looking for it at all. The term Entre Lagos (German: Between the Lakes) for the area of Mangochi assumes a precise geographical idea among the Portuguese, only the main trade routes ran via Petauke and the Copperbelt into the Bangweulu basin , because copper, gold and ivory came from there Lake Malawi only fish.

It looks like the Chewa migrated north, that is, settled the fertile highlands of the Viphya Mountains . After 1500, around iron, which the Chewa knew how to work, Nkhotakota developed into the most important trading post on the lake, reached by traders from Zanzibar at the end of the 18th century and soon followed by slave traders. Independently of these, the Yao , who hunted slaves for the Portuguese , migrated from the east to the Mangochi area at the beginning of the 19th century . Soon after, Nguni migrated from Natal to the Ntcheu and Mzimba areas . They came in small groups and hit a sparsely populated country.

Modern history (from 1859)

European discovery and early phase of colonization 1859–1891

On September 16, 1859, David Livingstone was the first European to reach the shores of Lake Nyasa , now known as Lake Malawi. In 1861 a group of missionaries led by Bishop Frederick Mackenzie tried to build a mission station on the banks of the island. They only got as far as the Zomba area . The malaria and attacks of Yao drove them back to the coast. In contrast, a group of Scottish missionaries were more successful in 1875. They founded the today's cities of Blantyre and Livingstonia and were staunch opponents of the slave trade. Because the missionaries had to be cared for, the African Lakes Company was founded in 1878 . This created its own protection force and their people often clashed with Arab slave traders. In 1883, Great Britain first sent a consul to the territory of the kings and chiefs of Central Africa to look after British citizens . The British Company (Company) constantly recruited more soldiers. One of them was officer Frederick Lugard . He and his people succeeded in driving the slave traders northwards. Another problem was the Portuguese who wanted to connect their colonies Angola and Mozambique. That is why they sent an expedition under Alexandre Serpa Pinto to what is now Malawi in 1889 . To keep the Portuguese away, the British pushed ahead with the development. On September 21, 1889, they established the Shire River Protectorate and appointed a British Commissioner. In the same year the British South African Company took over the further development of the area.

British colonial 1891–1964

The establishment of the colonial structures 1891–1918

Official British administration began on September 15, 1891 with the establishment of the Nyasaland District Protectorate . On February 23, 1893, the area was renamed the Protectorate of British Central Africa . The new administrator, Henry Hamilton Johnston , who also administered Northern Rhodesia (today's Zambia ), finally drove out the slave traders with the help of gunboats and Indian auxiliaries. His successor Alfred Sharpe brought tea, tobacco and cotton into the country. In order to be able to cultivate these products, large areas of land were expropriated and local people were driven out of the Shire Valley. These defended themselves against the occupiers and were not subjugated until 1904.

Sharpe remained in office (with a brief interruption) until 1910. On May 1, 1908, he became the first permanent governor of the Protectorate of Nyasaland . Since 1907, European immigrants, with seats on the Executive and Legislative Councils, had limited political influence. In 1911 their say was extended. Africans were not represented on these bodies. From 1903 to 1911, many Malawians left the country to get work in the mines of South Africa . The European settlers lacked labor. That is why the locals were banned from working in South Africa.

At the beginning of the First World War , imperial troops invaded northern Malawi from German East Africa (now Tanzania ) . The intruders could be repulsed with large-scale forced recruitment . A total of 18,920 men came to the King's African Rifles and another 191,200 men served as porters or members of the Home Guard.

The uprising of 1915 caused far greater problems for the colonial power. In recent years, locals without rights had converted to Christianity in increasing numbers. At the same time, they received school education. Local Christians became wandering preachers, but also saw the misery of their compatriots. Three of them not only preached the gospel to the people , but also told the audience, “Africa belongs to the Africans!” Under the direction of John Chilembwe , Charles Domingo and Elliott Kamwana , who were viewed as prophets, numerous Africans rose up against them Europeans. The British brutally suppressed the uprising.

The interwar period 1918–1939

In the interwar period, the British first worked out plans to unite Malawi with Kenya or Tanganyika . This and the disadvantage of Africans compared to white settlers led to the establishment of the Nyasaland Native National Association among Malawians in South Africa as early as 1920 . Local cells also emerged in the country itself. At the end of the 1920s, the European settlers demanded that Malawi be amalgamated with Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe ) and Northern Rhodesia. Because of the violent reaction from Africans to these plans, the colonial government buried the idea until 1939.

Final phase of the colonial period 1939–1964

When, on October 18, 1944, the British colonial administration decided on closer cooperation between Nyasaland and the two Rhodesia, Levi Mumba and like-minded people founded the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC). Its representative in London was the doctor Hastings Kamuzu Banda . This managed to talk the British colonial authorities out of plans for a Central African Federation for nine years . But on November 23, 1953, the federation became a reality. The NAC under Henry Chipembere , Kanyama Chiume and Dunduzu Chisiza , together with Zambian colleagues, fought the federation with strikes and demonstrations. In the legislative elections of March 15, 1956, the NAC won all five African mandates. On July 6, 1958, the popular Banda returned to his native land after 43 years. A short time later, on August 1, 1958, he was appointed party president of the NAC for life. In November, after Banda called for a boycott, only 16 Africans took part in the Federation Council elections. From February 15, 1959, there was massive unrest. Police stations were raided, prisons stormed and prisoners freed, airports blocked. The city of Fort Hill (now Chitipa) fell into the hands of the NAC. In this situation, the federal government declared a state of emergency on March 3, 1959 and deployed thousands of white soldiers to Malawi. After months of unrest and 51 deaths, calm was restored in June 1959. At the same time, the government arrested around 1,000 NAC people, including the entire leadership. The NAC was banned - but was re-established on September 30th as the Malawi Congress Party (MCP). Orton Chirwa took over the provisional management . But the unpopular federation was politically at an end. Banda was released from prison on April 1, 1960, and was elected MCP chairman on April 5, 1960. On June 16, 1960, the British colonial administration lifted the state of emergency. In August 1960 the British granted the country limited internal autonomy.

Before independence, the colonial authorities granted blacks the right to vote and stand for election in the 1961 constitution; however, this was limited by educational barriers and property requirements. Many women were active in the nationalist movements. In the August 1961 elections, women who met education and property requirements were allowed to vote. All European women and around 10,000 black women were allowed to vote.

In the legislative elections of August 15, 1961, the MCP won 22 of the 28 seats, including all of the African seats. Banda became the first African Prime Minister of the Protectorate on February 1, 1963. On December 31, 1963, the Central African Federation was officially dissolved. On July 6, 1964, the British colonial era ended and the protectorate of Nyasaland became the independent state of Malawi.

Independent Malawi (since 1964)

The Hastings Kamuzu Banda era 1964–1994

When independence was achieved in 1964, universal suffrage and thus unrestricted women's suffrage were introduced.

With the exception of the three seats reserved for the upper classes, the MCP won all seats in the parliamentary elections of 1964. On July 6, 1964, Hastings Kamuzu Banda became the first head of government of independent Malawi. Shortly after the founding of the state, the MCP broke up into two factions. Banda was in favor of pro-Western politics and only wanted to gradually replace the Europeans in administration and justice. The younger management members of the MCP, on the other hand, wanted only Africans in management positions as soon as possible. The head of government prevailed with his presentation and therefore dismissed three ministers on September 7th. Other ministers who disagreed with his view also resigned. When Banda was granted even more constitutional rights on October 29, 1964 - including judicial power - he became virtually the sole ruler. In February 1965, 200 supporters of the dismissed minister Chipembere tried to spark a popular uprising. Except for conquering the city of Mangochi , they did not succeed. They were soon expelled there too. The result was mass arrests. Nevertheless, on April 29 and May 3, new unrest flared up. But even this was suppressed by loyal troops until the end of May. After the republic was established, Banda became Malawi's first president on July 6, 1966. He introduced the one-party system . As a token of goodwill, Banda released 184 political prisoners on December 20, 1966 and promised amnesty to oppositionists willing to return . Former Foreign Minister Yatuta Chisiza was murdered on April 24, 1967, when he entered Tanzania, and his companions were arrested. A court sentenced her to death on June 14, 1968. The sentence was carried out on March 29, 1969, when those sentenced to death were hanged. In 1970 the president brought the last independent bodies to line. The four white judges of the Supreme Court resigned resignedly because of the constant interference of the head of state in their work. Opposition leaders have been arrested for alleged involvement in ritual murders .

Parliament amended the constitution in November 1970, making Banda president for life. In the April 1971 elections, only those candidates who had been chosen by Banda ran - and they were all elected. They then elected Banda as president for life. Politically unwanted white missionaries and unpopular journalists left the country or were expelled until 1973. Many black African migrants were also deported to their home countries. Violent attacks also forced thousands of members of the forbidden Jehovah's Witnesses religious community to flee to neighboring countries. In 1973, Minister Aleke Banda fell out of favor with Banda for telling a Zambian newspaper that he was the intended successor to his namesake. The country's 12,000 Asians came under pressure in an anti-Asian campaign over alleged exploitation of Africans. Some left the country, others fled to urban ghettos. The 1976 elections followed the same pattern as those in 1971. Another potential successor to Banda, MCP General Secretary Albert Muwalo Nqumayo , lost his post over alleged involvement in a coup plan. The early elections on June 29, 1978 were a tad more democratic. There was only one candidate in 33 of the 87 constituencies; in all the others, several MCP candidates competed against each other. The people voted out 31 previous parliamentarians. An attempted murder of Mozambique-based opposition politician Attati Mpakati, ordered by Banda, failed. In 1982, the former Justice Minister Orton Chirwa fell into the hands of the Malawian government while traveling along the national border. The court sentenced him and his wife to death on May 5, 1983. But this verdict was commuted to life imprisonment under pressure from human rights organizations, churches and Western donor countries. Chirwa died in Zomba prison in 1992. Bakili Muluzi , MCP general secretary and possible successor to Banda, fell out of favor in 1982 and resigned from the government in May 1982. In 1983 another attempted murder of Mpakati succeeded in Zimbabwe. Four politicians died in a car accident, including MCP General Secretary Dick Matenje . Allegedly, shortly before his death, he had strongly criticized Banda's policy.

In the parliamentary elections of June 29 and 30, 1983, there were single applications in 21 constituencies and multiple applications in the others. The country slipped more and more into political isolation because of its South Africa-friendly attitude and its support for the RENAMO rebels. Following threats from Mozambique, Malawi sent deserters from the Mozambican army and RENAMO rebels back to Mozambique. The parliamentary elections on May 27 and 28, 1987 went like the previous ones. There were single candidates in 38 constituencies and multiple candidates in the remaining MCP members. This time, however, 53 previous elected officials were voted out by the people. After the death of President Samora Machel , whom he hated , Banda changed fronts in the Mozambican civil war. The RENAMO was now the enemy and the FRELIMO government of Mozambique the friend. Between January 24 and 26, 1989, students at the University of Zomba boycotted lectures and demanded political reforms. A gasoline bomb attack in Lusaka, which was carried out on members of the Malawi Freedom Movement (MAFREMO), killed ten people in the Zambian capital. In March 1990, another opposition party was founded in exile, the Malawi Socialist Labor Party (MSLP). Its founders were previously members of the League of Socialists of Malawi (LESOMA).

The final phase of Banda's rule was ushered in. Western governments and aid agencies made the payment and remittance of money and aid conditional on the release of political prisoners. With the exception of Chirwa and Aleke Banda, almost all political prisoners were therefore able to return to freedom. Banda also had to fire his intimate partner and chief advisor John Tembo , the uncle of his "hostess", because Tembo was embroiled in financial inconsistencies. In exile in Zambia, MAFREMO, LESOMA and the Malawi Democratic Union formed the United Front for Multi-party Democracy (UFMD). The Malawi Democratic Party (MDP) was launched in August in exile in South Africa . On March 8, 1992, the Malawian Catholic Church openly opposed Banda. A letter written by eight Catholic bishops calling for the re-establishment of multi-party democracy was read out in all of their places of worship. On March 12, the Zambian opposition in Lusaka took the same line.

Blantyre and Zomba were hit by student protests from March 15-17. On March 23, 1992, the Alliance for Democracy (Aford) was founded underground and ex-MCP General Secretary Muluzi was elected its chairman. Contrary to promises to the contrary, Banda had the trade unionist and opposition activist Chakufwa Chihana, who had returned from exile, arrested on April 8 in Lilongwe. Because of the dire economic situation, mass strikes broke out in May. The protests were put down, with 37 people killed. The President experienced a bitter disappointment on June 2nd. The (reformed) Church of Central Africa , which in addition to Banda also included several cabinet members, criticized the human rights situation in the country and called for a return to multi-party democracy. The next parliamentary elections took place on June 26 and 27, 1992. The opposition called for a boycott. Because no or only one suitable MCP candidate stood for election in 50 of the 141 constituencies, hundreds of thousands of voters were unable to vote. In addition, a total of 62 previous parliamentarians were voted out by the people. Under foreign pressure, Hastings Banda released the imprisoned opposition politician Aleke Banda on July 10th. By October 8, more and more organizations joined the call for an end to one-party rule. They founded the Public Action Committee (PAC). The aged president finally gave in and promised a referendum on the number of parties (one- or multi-party system) in a radio address on October 18. Negotiations between the government and the PAC / Aford began just one day later. A presidential council was established in which both sides had an equal number of members.

The referendum was held on June 14, 1993. Aford chairman, who was arrested in April, was released the day before. With a turnout of 67.1%, the supporters of the multi-party system clearly won with 64.69%. But while all districts in the northern and southern regions voted for this system with majorities of 71 to 94%, the majority in eight of the nine districts in the central region - Banda's home - were in favor of the one-party system. The popular will was quickly implemented after the vote. On June 29th, the parliament deleted the constitutional article on the one-party system. The Malawi National Democratic Party (MNDP) was formed on August 19 and the United Democratic Front (UDF) in October . For the seriously ill Banda, the chairman of the presidential council, Gwanda Chakuamba , took over the affairs of state from October to December . The resolution that Banda was president for life was overturned by Parliament on November 17, 1993. When three unarmed members of the MCP youth organization, the Malawian Young Pioneers, were killed on December 2 , the army launched a disarmament campaign against the Young Pioneers without a parliamentary resolution. They fought violently. 32 people died. 2000 of the 7000 young pioneers fled to Mozambique with their weapons from the superior army. At the end of December the army had disarmed the remaining pioneers. In the UDF primaries, Muluzi prevailed with 47.3% versus 33.6% for Aleke Banda and became their official presidential candidate. Muluzi was also supported by other opposition parties.

Eight parties (alliances) competed in the parliamentary elections on May 17, 1994. With a turnout of 80.02%, the UDF received 46.44% of the vote and 85 seats, the MCP 33.65% and 56 seats and the Aford 18.94% and 36 seats. Four candidates ran for the presidential elections that took place at the same time. Muluzi (UDF) won with 47.15% of the vote. The beaten Banda (MCP) received 33.44%, Chihana (Aford) 18.89% and Kamlepo Kalua ( Malawi Democratic Party ; MDP) 0.52%. However, the country experienced a political tripartite division. Muluzi and the UDF won in the south, Banda and the MCP in the center, and Chihana and the Aford in the north. On May 25, 1994, Muluzi presented his 25-person cabinet with politicians from the UDF, MNDP and UFMD. Three cabinet posts were kept vacant for the Aford. The injured Banda withdrew from politics in September and left the MCP chairmanship to his deputy Chakuamba.

The Muluzi era 1994–2004

Due to frequent droughts, the AIDS epidemic and the mismanagement under Banda, Muluzi came into a difficult legacy. In addition, the Aford refused to enter the government, so that Muluzi did not have a parliamentary majority. Hastings Kamuzu Banda, John Tembo and three senior police officers were arrested and charged on January 6, 1995 for the 1983 deaths of Dick Matenje and three other politicians. The trial of her began on April 24th and ended in an acquittal on December 23rd for lack of evidence. Under pressure from the IMF, the new government had to cut administrative jobs, shut down unprofitable state-owned companies, devalue the national currency, and raise prices and taxes. As a result, unemployment increased, poverty in the country increased and the crime rate soared. This led to a massive loss of popularity of Muluzi's rule among the Malawian people. At the same time, the government struggled with corruption problems in its own leadership. In order to fight the serious corruption in government and administration, an anti-corruption office was created in February 1996.

Aford entered government in July 1995, but it and the MCP boycotted parliamentary sessions from June 1996 to April 3, 1997. The reason for this was attempts by the UDF to poach them from the ranks of the MCP and Aford in order to be able to form a stable government of their own. Banda died on November 25, 1997 and was passed with a state funeral. The National Electoral Commission (MEC) was strengthened on June 5, 1998 through new laws and resolutions. The parliamentary elections of June 15, 1999 led to a victory for the UDF with a very high turnout of 92%. However, it did not receive an absolute majority, but rather 47.28% of the votes and 93 mandates. In addition, the MCP achieved 33.82% and 66 seats, the Aford 10.56% and 29 seats. Independent candidates received 7.13% and four seats. The other eight small parties came away empty-handed. Muluzi just won the presidential elections with 52.38%. Chakuamba (MCP-Aford) got 45.17% of the vote and accused Muluzi of electoral fraud. Of the other three applicants: Kalua (MDP) 1.45%, Daniel Nhumbwa ( Congress for National Unity ; CONU) 0.52% and Bingu wa Mutharika ( United Party ; UP) 0.47%. The MCP-Aford filed election complaints with the MEC in 16 districts. At the same time, their supporters set fire to mosques - Muluzi is a Muslim - and destroyed the shops of UDF supporters. In a final verdict, the Supreme Court finally declared the elections legal. In September 2000, the Anti-Corruption Agency and the Audit Commission published a joint report. Several ministers were accused of collecting money for fictitious orders. Therefore, on November 2, 2000, Muluzi dismissed the entire cabinet. Local elections were held for the first time on November 21, 2000. Of the 860 seats to be allocated, the UDF 610, the Aford 120 and the MCP (already running in two parliamentary groups) received 84 mandates. However, the low voter turnout of 14.2% showed the people's dissatisfaction with the politicians.

After the MCP, the UDF split in 2001. Some of the previous members founded the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) in 2001 . The founding convention of the NDA was to take place in Blantyre. But John Chikakwiya, the city's UDF mayor, forbade this meeting. He was charged and sentenced in a trial on February 21, 2001 to two weeks in prison for violating democratic rights. From January 16, the trials of dozens of corrupt ministers, parliamentarians and officials began. And in March, the police arrested six people for an alleged attempted coup. In order to prevent parliamentarians from being enticed away, parliament passed a law in May that led to automatic loss of seats when changing parties. One wanted to avoid further fragmentation of the parliament. John Tembo was elected as the new chairman of the MCP in place of Chakuamba by a large majority of MCP district chairs. The loser declared this operation illegal. Brown Mpinganjira , chairman of the NDA, was arrested in October for alleged involvement in the March coup attempt . However, a court ruling reversed this process in December and Mpinganjira was released.

Since Malawi had sold food supplies on the orders of the IMF, a famine broke out the following year after the drought of 2001, affecting millions of people. The minister responsible for distributing the aid supplies, Leonard Manguluma, was dismissed in August 2002 for failure. International aid for the needy population was slow to arrive due to the corruption within the government.

Muluzi tried several times to amend the constitution in a way that would have enabled him to exercise a third term. After these efforts failed, he managed to get Mutharika, who had defected from the UP, to run as a UDF candidate for the presidential elections. At the MCP in May 2003 Tembo and Chakuamba ran as presidential candidates for the preliminary round. The loser Chakuamba left the MCP because of his defeat in January 2004 and founded the Republican Party (RP). Aleke Banda stepped over to the newly formed People's Progressive Movement because of the election of Mutharika as a presidential candidate from the UDF . At the same time, Vice President Justin Malewezi also moved to PPM. He then ran as an independent for the 2004 presidential election. Further splits from the three major parties followed. Aford members founded the Movement for Genuine Democratic Change (MGODE) and dissatisfied MCP members the New Congress for Democracy .

The elections had to be postponed by two days due to insufficient voter registration. Political fragmentation resulted in five presidential candidates and 15 parties (plus independents) running in the May 20, 2004 elections. With a turnout of 54.32%, there was no clear winner in either election. The UDF duo Mutharika / Cassim Chilumpha received 35.89%, Tembo and Peter Chiwona (MCP) 27.13%, Chakuamba / Aleke Banda (RP) 25.72%, Mpinganjira / Clara Makungwa (NDA) 8.72% and Malewezi / Jimmy Koreia-Mpatsa (Independent) 2.53% of the vote. Mutharika became the new president of the country. Due to a lack of voter registers, six of the 193 constituencies were not elected. Of the 187 mandates awarded, the MCP 58, the UDF 49, the Mgwirizano Coalition 27, the NDA 8, Aford 6 and the CONU received one seat. Independent candidacies were successful in 38 cases. International election observers, however, judged the two elections to be neither free nor fair.

The Mutharika era

Since the RP (15 seats) and MGODE (three seats), which belong to the Mgwirizano, formed a coalition with the UDF together with the majority of the independents, the UDF was able to continue to govern. In October 2004, former Treasury Secretary Friday Jumbe was arrested on charges of unlawful grocery sales in a time of need and sentenced to five years in prison at the trial. President Mutharika accused his UDF of sabotage against the anti-corruption agency ACB. He therefore resigned from the UDF on February 5, 2005 and founded the Democratic Progressive Party on March 16, 2005 . 83 MPs from his ruling coalition followed him in this step. Because of this, in their opinion, illegal step, UDF parliamentarians demanded that a dismissal procedure be opened against Mutharika. The debate began on June 24th, involved serious mutual allegations, and ended on January 10th, 2006 for the withdrawal of the deposition proceedings.

A cabinet reshuffle forced Chakuamba, President of the RP, to leave the government. Because of the devastating drought in the south and center of the country in 2004, the government declared the entire state to be a disaster area on October 15, 2005, faced with millions of starving Malawians. On October 18, 2005, the anti-corruption authority required ex-President Muluzi and ministers of his government to provide precise information about their income during their term of office. The background to this was substantial asset growth in the millions among this group of people. The incumbent Vice President Chilumpha was also suspected of corruption. Therefore, on February 9, 2006, Mutharika released him. But the Supreme Court overturned this decision a day later, since the constitution only allows parliament to remove a vice-president from his office. However, the police arrested Chilumpha again on April 28, 2006, along with businessmen Yussuf Matumula and Rashid Nembo. This time on charges of a plot to murder President Mutharika. Nembo was acquitted by a court in January 2007 for lack of evidence. The trial of Chilumpha and Matumula is currently (as of February 25, 2007) before the Supreme Court in Blantyre.

In the course of the presidential election on May 20, 2014, Peter Mutharika won the competition among several candidates. He wins with 36.4% in front of Lazarous Chakwera with 27.8% and other candidates for office. He was also subject to the previous incumbent Joyce Banda , who had previously wanted to have the election declared invalid.

See also

literature

In German language

- Frank Hülsbörner, Peter Belker: Malawi. Land of fire . Conrad Stein Verlag, 1995. ISBN 3-89392-225-3

- Alice Petersen: Livingstone's black heirs. Colonial Rule and African Elites. The example of Malawi . Horlemann Verlag, 1990. ISBN 3-927905-13-5

- Ilona Hupe, Manfred Vachal: Travels in Zambia and Malawi . Ilona Hupe Verlag, 2006. ISBN 3-932084-32-2

In English

- Owen JM Kalinga, Cynthia A. Crosby: Historical Dictionary of Malawi . 3rd edition. Scarecrow Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8108-3481-2 (standard work)

- Robert I. Rotberg: The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia 1873–1964 . Harvard University Press, 1974. ISBN 0-674-77191-5

- Anthony Woods, Melvin E. Page: The Creation of Modern Malawi . Westview Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8133-1402-X

- Marin Chanock: Law, Custom and Social Order: The Colonial Experiance of Malawi and Zambia . Greenwood Press, 1998. ISBN 0-325-00016-6

- George Shepperson, Thomas Price: Independent African: John Chilembwe and the Origins, Settings and Significance of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915 . Edinburgh University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-85224-540-8

- Harvey J. Sindima: Malawi's First Republic: An Economic and Political Analysis . University Press of America, 2002. ISBN 0-7618-2332-8 (for the period 1964-1994 )

- Colin Baker: Revolt of the Ministers. The Malawi Cabinet Crisis 1964–1965 . IB Tauris & Co., 2001. ISBN 1-86064-642-5

- Hari Englund: A Democracy of Chameleons. Politics and Culture in the New Malawi . The Nordic Africa Institute, 2003. ISBN 91-7106-499-0 (for the most recent)

Web links

- Historical periods Malawi (English)

- Encyclopedia Britannica (English)

- Elections and democratization in Malawi ( Memento of November 24, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (English; PDF; 751 kB; archive version)

- Democratic development in the 1990s (English; PDF; 1.04 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ uca.edu: British Nyasaland (1907-1964)

- ^ A b Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 243.

- ^ A b c June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 7.

- ↑ Xinhua: Mutharika déclaré vainqueur de la présidentielle au Malawi . Announcement of May 31, 2014 on www.afriquinfos.com ( Memento of July 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (French)