Limes Mauretaniae

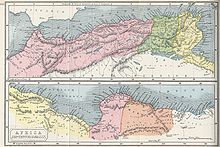

In modern research, the Limes Mauretaniae is the part of a 4,000-kilometer North African border fortification and security line ( Limes ) of the Roman Empire between the Atlantic coast and most of the Roman Empire that runs between Auzia ( Sour El-Ghozlane , Algeria ) and Numerus Syrorum ( Maghnia , Morocco ) called Limes Tripolitanus in what is now Tunisia .

function

In Roman North Africa there were no continuous border fortifications such as B. Hadrian's Wall in Britain. The transitions on the limes Africanus into the free tribal areas were fluid and were only monitored by the garrisons of a few outposts. Their security tasks were made more difficult by long communication channels and the lack of a clear border zone. The greatest danger came from the Berber nomadic tribes, which - in addition to the eastern border, which was constantly threatened by the Sassanid Persians - gave Rome another secondary theater of war there. The chain of castles was primarily intended to mark the Roman territory. In large areas, however, the facilities also served to control and channel the migration of nomadic tribes or peoples, including monitoring and reporting their activities, and as a customs border. This Limes was not so much a military border security system, but rather a monitored economic border to the free nomadic peoples and hill tribes. The Limes could not have withstood a coordinated military attack.

history

In the course of the disputes between Gaius Iulius Caesar and the Pompeians , after the battle of Thapsus in 46 BC. Divided the previously independent Numidia . One part fell to Mauritania , the other was added to the Roman province of Africa . The Kingdom of Mauritania was founded in 33 BC. BC inherited from King Bocchus II in his will to Rome. This means that this empire was initially under direct Roman rule. Augustus put Juba II in 25 BC. As ruler of a client state , which however did nothing to pacify the hinterland. In 23 AD his son Ptolemy succeeded him to the throne and put down a revolt against Rome. On the occasion of Ptolemy's visit to Rome, however, Caligula had him murdered in AD 40 and annexed his empire. The unrest that ensued was put down in AD 44. Claudius divided the area of the former kingdom into the provinces of Mauretania Caesariensis (capital: Caesaria [now Cherchell ]) and Mauretania Tingitana (capital initially Volubilis , later Tingis [now Tangier ]).

Unrest and revolts were frequent in the African provinces during Roman rule. In 238 AD, the governor of Africa , Gordian I , and his son Gordian II (as co-regent ) were proclaimed against their will by the Roman Senate as counter-emperor to Emperor Maximinus Thrax . However, their troops were defeated by the Legio III Augusta . Under Emperor Diocletian , the new province of Mauretania Sitifensis was separated from Mauretania Caesariensis , which was named after its capital Sitifis (today Sétif ).

In the 5th century both provinces fell to the Vandals . Parts of Tingitana , Caesariensis and Sitifensis belonged to the Byzantine Empire after the destruction of the Vandal Empire by the Byzantine general Belisarius in the 6th century , until the Islamic expansion in the 7th century put an end to the rule of Byzantium.

topography

The North African Limes protected the provinces on the Mediterranean Sea, which stretched roughly between 90 and 400 kilometers inland. The geography of the provinces of Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Tingitana is roughly divided into a coastal strip of different widths, followed by partly very fertile mountain regions or river valleys, transitioning into steppe and desert steppe and mountain regions. The inhabitants of Mauritania, especially in the Tingitana , were probably semi-nomadic hill tribes related to the Iberians .

The eastern border of the province of Mauretania Caesariensis (identical to the eastern border of the later province of Sitifensis ) ran approximately on a line west of the Cap Bougaroun on the Ampsaga river to the eastern end of the Chott el-Hodna and further west into the steppe landscape. This line also separated the settled population from the nomads and formerly formed the border of the area ruled by Carthage . The southern border approached the transition from the province of Nubia to the province of Mauretania Caesariensis, the coast along the northern slope of the Tell Atlas . The area ruled by the Romans thus shrank from the usual 400 kilometers of geographic depth to just 95 kilometers. The more north-oriented border in the Mauretania Caesariensis roughly coincided with the precipitation limit required for agriculture. The Roman armed forces, which were poorly represented here, were also decisive for the initial delimitation of the territory.

The Roman sphere of influence, which was originally restricted to the coast of the Caesariensis, was expanded further south in the Maghreb from the 1st to the 3rd century for economic reasons. This inevitably led to unrest among the local population, who feared for their livelihoods. In the west the river Mūlūyā / Muluccha formed the border with the province of Mauretania Tingitana .

A vast and barren plain separates Algeria from Morocco. In the north, the foothills of the Rif Mountains drop steeply into the sea, preventing a direct land connection along the coast. The connection between Caesaria and Tingis was therefore normally maintained by sea, as there were no areas between the two provinces that were economically used by the Romans.

The Roman influence and control in the province of Mauretania Tingitana extended on the Atlantic coast to the river Bū Rağrağ / Regreg / Sala near Rabat (Sala) and the plateau around Volubilis , a very productive agricultural area, bounded by the Atlas . The northern Rif and Atlas Mountains had obviously never been permanently occupied by the military.

The road network laid out by the Romans in North Africa provided good and time-saving logistical connections for trade and supplies for their widely deployed troops. In Caesariensis there were three roads running parallel to the coast. As a rule, however, it was unpaved slopes and not paved roads. Natural traffic routes - such as rivers - did not exist in the Caesariensis province . The border to the steppe fringes was well developed in terms of traffic, mainly for military reasons.

economy

The main export products of both provinces were wood and purple as well as agricultural products and also wild animals from Tingitana for the circus games . The Moorish tribesmen who lived here were often recruited as auxiliary troops, especially for the light cavalry. The people living on the coast lived in a symbiotic relationship with the nomads of the steppe and the hill tribes. At the beginning of the dry season, nomads and hill tribes moved to the coastal regions, hired out as workers and exchanged agricultural products for animals from their herds.

Border and fortifications

Rome's struggle against the barbarians was always determined by the numerical superiority of the opponent, so that it was often forced to compensate for its inferior personnel by its manual skills and the use of technology. The Limes of the two Mauritanian provinces was not a continuous fortified border wall because of the considerable distance from the Atlantic to the eastern border of the Caesariensis province . Instead, barriers ( clausurae ) were mainly built in the valleys of the Atlas as well as ditches ( fossata ), ramparts, but also a number of watchtowers and forts. The facilities were connected by a road network designed according to strategic aspects. The border security system adapted largely to the conditions of the topography, but also to the behavior and habits of the local ethnic groups , and was therefore in some cases hardly paved. The border expansion in Mauritania was intensified at the beginning of the 1st century AD and expanded a little further south until the 3rd century.

North of the Chott el-Hodna in the area of the Monts du Hodna there were a number of clausurae , which consisted of ramparts, adobe walls or rampart and ditch systems built on the slopes up to a length of 60 kilometers and thus narrowed the valley passages to a narrow passage . The priority, however, was to seal off the mountainous area by using natural obstacles. The Roman dominated area of the province of Mauretania Caesariensis was secured by a line of fortifications running along the Oued Chéllif river, which consisted of a series of forts - built under Hadrian - about 30 to 50 kilometers apart. The shallow depth of the ruled area suggests that the hill tribes living here could never be subjugated. In the north-west of the province, the Rif Mountains drop steeply into the sea, preventing a direct land connection between the provinces. From about AD 197 the Severians built a series of forts in the western Caesariensis on the northern border of the plateau. The last fort in this series was Numerus Syrorum ; it was to the west in front of the Tlemcen Mountains. The Hadrianic chain of castles on the Oued Chéllif river now served as an additional barrier and containment line.

Mauretania Tingitana was difficult to control and defend due to its topography. In the northeast, the tribes of the Rif Mountains were a constant cause for concern. Initially, there was also a lack of a security line through watchtowers to better monitor the mountain range. The atlas, which runs southeast and is up to 4000 meters high, merges quite abruptly into the Sahara on its eastern side . None of these regions could be subjugated by Rome. Likewise, the easily accessible coastal areas of central and southern Morocco south of Rabat remained outside the Roman sphere of influence.

The fort line in the Tingitana was mainly based on the coastline or was at least close to the coast and served to ward off Moorish attacks and pirate attacks from the Rif and the Atlas. Because of the pirate threat , both the coastal protection and the inland Sububus (Oued Sebou) river were reinforced from the 2nd century onwards by building forts in Thamusida, Banasa and Souk el Arba du Rharb. The Roman troops of the province concentrated mainly on the forts on the coast and around the provincial metropolis of Volubilis . Sala / Rabat and Volubilis , however, were outside the protected area of the forts on the river front. Volubilis was exposed inland and therefore required greater defense efforts. From the second half of the 2nd century onwards, a city wall and numerous camps and observation posts served to protect the city. The Sala, located on the coast, was sealed off from the Atlantic to the Oued Bou Regreg by an eleven-kilometer-long ditch, which was partially reinforced with a wall, four small forts and around 15 watchtowers. Additional forts were built in Tamuda / Titwān, Souk el Arba du Rharb and Kasr el Kebir on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

Due to increasing attacks by the local tribes under Diocletian in the second half of the 3rd century the border in the Tingitana was reduced to the line Frigidae - Thamusida . The area around Volubilis was abandoned, while the city of Sala could probably be held until the early 4th century.

In the early days of the Principate , forts were rare in the provinces, as the troops were widely deployed. The forts and watchtowers built later were mostly rectangular and covered an area of 0.5–0.12 hectares. The smaller military posts, called centenaries or burgi , had a size of only 0.01-0.10 hectares, reinforced walls, no windows and only a small crew. They were strategically placed on the site and were used, among other things, to transmit messages by exchanging signals with the neighboring bases.

The armed forces

To defend and protect against rebellions and raids by nomadic tribes and hill tribes, only the Legio III Augusta was stationed outside of Egypt as the only legion in North Africa. This initially gives the impression of an overstretching of the forces, but was based on the economic assessment of the defensive worth of arable land in contrast to regions of lesser importance, which justified a less costly defense effort. During Hadrian's visit, for example, extensive stretches of the peripheral areas along the deserts were not monitored by the Romans at all. The existing armed forces were tasked with protecting the border line against attacks from the steppe, mountainous and desert areas, but on the other hand were not allowed to pose a threat to Rome. This balancing assessment between sufficient military means to ward off an external threat and at the same time avoidance of an internal threat applied in principle to all provinces. Although the military potential was obviously overwhelmed for a short time, the legion and auxiliary units in North Africa were basically able to fulfill their mandate.

Until the early 1st century AD there were no permanent military bases (except in Ammaedara ). Legion and auxiliary units of the province were mainly stationed near the coast or near port cities. The location of the Legion's stationing changed several times over the course of time for strategic reasons, first from Ammaedara to Theveste and finally to Lambaesis . Under Gordian III. The Legion was dissolved in 238 AD due to the successful suppression of a revolt under Gordian I and II, only to be re-established in 256 AD during the reign of Emperor Valerian . In the meantime, depending on the threat, the armed forces were briefly reinforced. In the time of Tiberius, the IX. Legion moved from Pannonia to North Africa to fight rioting. Also Antoninus Pius increased due again erupting riots troops in Mauritania.

In the 2nd century the auxiliary forces in the Caesariensis consisted of three alae and ten cohorts , a total of around 7,000 men, and in the Tingitana of five alae and at least ten cohorts, a total of around 8,000 men. The auxiliary units consisted of soldiers from Gaul, Italy and North Africa. From the 4th century onwards, more and more Berber tribal associations were recruited. The troop strength changed only insignificantly. In the provinces, however, the normally strived for ratio of 1: 1 between legion and auxiliary units did not apply. It was significantly less favorable. In late antiquity, according to Notitia Dignitatum, three commanders shared the power of command over the troops stationed on this Limes ( Limitanei and Comitatenses ) . These were:

- for Tingitaniam (western Algeria, Morocco) of the Comes Tingitaniae ,

- for intra Africam (Tunisia, Algeria, western Libya) of Dux et praeses provinciae Mauritaniae et Caesariensis .

The latter was under the command of the Comes Africae , the commander of the African field army ( Comitatenses )

fleet

Since Marcus Aurelius , Rome, the undisputed sea power in the Mediterranean, has been forced to station its own naval unit in Caesarea under the command of a dux per Africam, Numidiam et Mauretaniam , because of the omnipresent pirate threat . The Mauritanian fleet ( classis Mauretanica ) existed since the end of the 2nd century AD (it was probably established around 176 AD). It is likely that these were essentially Liburnians , with a trireme as the flagship . Initially only one squadron , which was composed of units from the Syrian and Alexandrian fleets as an intervention force, this fleet association ultimately proved to be too weak to effectively prevent the attacks of the Moorish tribes on Hispania that began after 170 AD . The fleet was used to protect the north-west African and Spanish areas, especially the province of Baetica . Her other tasks included securing the Strait of Gibraltar and escorting troops and goods from Europe to Africa. Their main base was in the provincial metropolis of Caesarea (Cherchell), other bases were in

- Cartennae ( Ténès ),

- Icosium ( Algiers ),

- Portus Magnus (Arzew / Béthioua ),

- Saldae ( Bejaia ) and

- Tipasa .

literature

- Nacéra Benseddik: Les troupes auxiliaires de l'armée romaine en Maurétanie Césarienne sous le Haut Empire. Algiers 1979.

- Maurice Euzennat : Le Limes de Volubilis. In: Studies on the military borders of Rome . Vol. 6 (1967), p. 194 ff.

- M. Euzennat: Le Limes de Tingitane. La frontière méridionale. Paris 1989.

- Margot Klee: Limits of the Empire. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-534-18514-5 .

- Nigel Rodgers : The Roman Army. Tosa published by Carl Ueberreiter, Vienna 2008.

- Margaret M. Roxan : The auxilia of Mauretania Tingitana. In: Latomus . Vol. 32 (1973), p. 838 ff.

- John Warry: Warfare in The Classical World. Salamander Books, London 1980, ISBN 0-86101-034-5 .

- Derek Williams: The Reach of Rome. Constable and Company, London 1996, ISBN 0-09-476540-5 .

- Hans DL Viereck: The Roman fleet, classis Romana. Koehlers 1996, ISBN 3-930656-33-7 , p. 257.