Artabanes

Artabanes ( Greek Ἀρταβάνης , from Old Armenian Արտաւան (Artawan), bl. 538 - 554 ) was an Eastern Roman (Byzantine) general of Armenian origin who served in Justinian's army (reign 527-565). Originally he was a rebel against Roman rule over parts of Armenia, which is why he fled to the Sassanids . However, he soon returned to the Eastern Romans. Artabanes served in the Praetorian Prefecture of Africa , where he earned a reputation for killing the rebel Guntarith and securing Roman rule over the province. He was engaged to Justinian's niece Praejecta , but (allegedly) did not marry her because of the resistance of the Empress Theodora . After being recalled to Constantinople , he participated in a failed plot against Justinian in 548/549. After his complicity was revealed, he was soon pardoned and sent to Italy to fight in the Gothic War, where he contributed to a decisive Eastern Roman victory over the Merovingians in the Battle of Casilinus in 554.

Early years

Artabanes was a descendant of the Arsacids . These had been ousted by the Sassanids in Persia in 226, but had still provided kings in Armenia until 428. A branch of this line ruled in the 6th century in a series of autonomous "princes" on the eastern edge of the Eastern Roman Empire. Artabanes' father was called Johannes, his brother also had this name.

Revolt against the Eastern Roman Empire

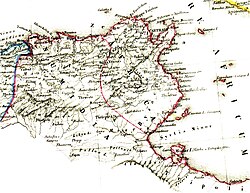

In the years 538-539 Artabanes, who was apparently still a very young man at that time, participated in an Armenian conspiracy against Acacius , the Roman governor of the province of Armenia Prima , whose excessive tax demands and cruel behavior had made him unpopular in the province . Artabanes himself killed Acacius. Shortly afterwards Artabanes could also have killed the Eastern Roman magister militum Sittas , who had been sent by Justinian to suppress the rebellion, in a skirmish between Eastern Roman and Armenian troops at Oenochalacon. Prokopios of Caesarea describes two versions: after one Artabanes killed Sittas, after the other an otherwise unknown Armenian soldier named Solomon. Artabanes' father tried to reach an agreement with Sitta's successor, Bouzes , but was murdered by him. This act forced Artabanes and his followers to seek the help of the Persian great king Chosrau I. After arriving in Persia, Artabanes and his followers took part in Chosrau's campaigns against the Eastern Romans.

Return to Eastern Roman services

Around 544, perhaps even 542, Artabanes, his brother Johannes and several other Armenians deserted back to the Eastern Roman camp. The reason may have been the Persian expansion policy in the Caucasus, which made the Sassanids appear more dangerous than the Romans.

Service in Africa

In 545 Artabanes and his brother were entrusted with the management of a small Armenian unit and sent to the newly established Praetorian Prefecture of Africa in 534 . There the Eastern Romans were involved in a lengthy war with Moorish tribes . Shortly after their arrival, Johannes died in the battle of Sicca Veneria with the rebel forces of the renegade General Stotzas . Artabanes and his troops remained loyal to the magister militum Areobindus during the rebellion of the dux Numidiae Guntarith . Guntarith, who was allied with the Moorish prince Antalas , marched on Carthage and seized the city gates. At the urging of Artabane and others, Areobindus decided to face the rebels in open battle. Both armies seemed equally strong until Areobindus fled to a nearby monastery in a panic and sought asylum. The troops loyal to him fled and Carthage fell to Guntarith.

Areobindus was murdered by Guntarith, but Artabanes had Guntarith give him a guarantee of his own safety and then entered his service. Artabanes secretly planned an intrigue against his new master. A little later he was entrusted with a punitive expedition against Antalas' Moors. He marched south under Kutzinas with an allied Moorish auxiliary force . Antalas' troops fled from him, but Artabanes did not pursue them and returned. According to Prokopios, he considered marching to Hadrumetum and strengthening the city's loyal garrison with his troops, but then decided to return to Carthage and stick to his plan to assassinate Guntarith.

On his return to Carthage, he justified his decision to retreat, arguing that it would have taken the whole army to defeat the Moors. He urged Guntarith to go into the field himself. At the same time he conspired with his nephew Gregorius and some of his Armenian bodyguards to kill the usurper (although Gorippus insists that the Praetorian prefect Athanasius was the head of the conspiracy). On the eve of the army's withdrawal in May, Guntarith held a banquet. He invited Artabanes and Athanasius to lie on the same couch as himself, which was tantamount to an award. During the feast, the Armenian bodyguards attacked Guntarith's sentinel; Artabanes himself fatally injured Guntarith.

This deed in 546 meant great fame and honor for him: Praejecta , the widow of Areobindus and niece of Justinian, who had wanted to marry Guntarith, rewarded him richly, and the emperor appointed him the new magister militum of Africa . Although he was already married to one of his relatives, Artabanes became engaged to Praejecta. He sent a message to this effect to Constantinople and asked the emperor to release him from his command so that he could marry Praejecta.

Constantinople: conspiracy against Justinian

A little later Artabanes was actually called back to Constantinople, his successor as army master was Johannes Troglita . He received numerous honors from Justinian, such as magister militum praesentalis , comes foederatorum and honorary consul . Despite these awards and his general popularity, he did not succeed in marrying Praejecta: his former wife traveled to the capital and presented her case to the Empress Theodora . The empress forced Artabanes to keep his first wife, and the Armenian only succeeded in divorcing her after Theodore's death in 548. At this point, however, Praejecta had already been remarried.

Annoyed by the matter, Artabanes became part of a conspiracy known as the "Armenian Coup" or the "Artabanes Conspiracy". The real man behind, however, was a relative of Artabanes, called Arsaces , who planned the murder of Justinian and the elevation of his cousin Germanus to emperor. The conspirators assumed that Germanus would be in favor of their plan, because the latter was angry about Justinian's interference in the last will of his recently deceased brother Boraides , who originally favored Germanus, but now the daughter of Boraides. The conspirators first approached Germanus' son Justin and initiated him into the conspiracy. Justin immediately informed his father, who in turn informed the comes excubitorum Marcellus . To find out more about their plans, Germanus met with the conspirators in person while a servant of Marcellus listened closely. Although Marcellus hesitated to alert Justinian without further evidence, he revealed the plan to the emperor. Justinian ordered the arrest and questioning of the conspirators, but otherwise the conspirators were treated with remarkable indulgence. Artabanes was relieved of his offices and placed under arrest in the imperial palace, but was soon pardoned. Evidently there was a lack of evidence, because if the emperor had been convinced of the guilt of the accused, he would undoubtedly have acted less leniently.

Service in Italy

In 550 Artabanes was appointed the new magister militum per Thracias to take command of the aged Senator Liberius over a military operation in Sicily that had recently been overrun by the Ostrogothic king Totila . Artabanes failed to reach the troops before leaving for Sicily, and his own fleet was held in the Ionian Sea by severe storms . Nevertheless, he finally reached Sicily and took command of the Roman troops stationed there. He besieged the Ostrogoth garrisons that Totila had left behind on the island and quickly forced them to give up. He stayed in Sicily for the next two years. According to Prokopios, the inhabitants of the town of Croton on the Italian mainland , which was besieged by the Goths, repeatedly sent for help, but Artabanes remained inactive.

In the year 553 Artabanes crossed over to Italy and joined the army of Narses as a sub-general. Under the influence of the Frankish invasion of Italy in the late summer of 553, Narses ordered Artabanes and other generals to occupy the passes of the Apennines and to slow down the enemy advance. After an Eastern Roman contingent had been defeated at Parma , all the other generals withdrew to Faventia until a messenger from Narses convinced them to return to the Parma area. In 554, Artabanes was stationed in Pisaurum with Eastern Roman and Hunnic troops. At Fanum he surprised the Frankish vanguard under Leutharis , who was on their way back to Gaul after a raid through southern Italy . Most of the Franks were killed and in the general commotion most of the prisoners managed to escape. Artabanes did not attempt to attack Leuthari's main army as it outnumbered his by far. Then he marched south, joined Narses main army and accompanied him on his campaigns against the Franconian Butilin . In the decisive Eastern Roman victory in the Battle of Casilinus , together with Valerianus, he commanded the cavalry on the left Eastern Roman flank, which was hiding in the forest to encircle the Franks according to Narses' plan. After this event nothing is known about Artabanes.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, p. 125.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 125, 1162.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 125, 255, 641.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 108, 643.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 108-109, 126, 575.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, p. 126.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 126-127, 143, 576; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, p. 146.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 125, 127, 576, 1048; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, p. 146.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 127-128, 1048-1049; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, p. 67.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, p. 128; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, pp. 66-67.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 128-129; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, p. 68.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, p. 129; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, pp. 69, 255-256.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, p. 129; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, p. 260.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 129-130.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, pp. 130, 789-790.

- ^ Jones, Martindale, Morris (eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 3, A. 1992, p. 130; Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. Volume 2. 1958, p. 279.

literature

- John B. Bury : History of the Later Roman Empire. From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian. Volume 2. Dover, New York NY 1958 (ND of 1923 edition).

- Arnold HM Jones , John R. Martindale , John Morris (Eds.): The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire . Volume 3: John R. Martindale: AD 527-641. Volume A: Abandanes - ʿIyāḍ ibn Ghanm. Reprinted edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-20160-8 .

- Alexios G. Savvides, Benjamin Hendrickx (Eds.): Encyclopaedic Prosopographical Lexicon of Byzantine History and Civilization . Vol. 1: Aaron - Azarethes . Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 2007, ISBN 978-2-503-52303-3 , p. 402.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Artabanes |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Eastern Roman general of Armenian origin |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 6th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 6th century |