Sousse

|

سوسة Sousse |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Coordinates | 35 ° 49 ' N , 10 ° 38' E | ||

| Symbols | |||

|

|||

| Basic data | |||

| Country | Tunisia | ||

| Sousse | |||

| ISO 3166-2 | TN-51 | ||

| Residents | 173,047 (2004) | ||

| Metropolitan area | 432,171 (2004) | ||

| founding | approx. 900 BC Chr. | ||

| Culture | |||

| Twin cities | see under town twinning | ||

Sousse ([ suːs ], Arabic سوسة, DMG Sūsa ) is a port city on the Mediterranean Sea and also the third largest city in Tunisia . The name is of Berber origin; Corresponding parallels can be found in Libya . In the south of Morocco , an entire region is known as Bilād as-Sūs .

The city is located around 130 kilometers south of the Tunisian capital Tunis in the south of the Gulf of Hammamet on the Mediterranean Sea. The city has 221,530 inhabitants, with the surrounding area 559,876 (2014). It is the capital of the Sousse Governorate ( wilāyat Sousse /ولاية سوسة / wilāyat sūsa ) (2014: 699.001 inhabitants) and metropolis of the Tunisian Sahel .

history

Sousse was founded in the 9th century BC. Founded by the Phoenicians as a trading post with the name Hadrumetum and has been settled since then. In the 3rd Punic War , Hadrumetum escaped destruction by the Romans because it broke away from Carthage in time. Under Roman rule, the city experienced an economic boom until the 3rd century AD. Repressions for participating in the Gordian Uprising of 238 led to its gradual decline. In the 5th century came the rule of the Vandals and the renaming in " Hunerikopolis " (after King Hunerich ). After the Byzantine reconquest by Belisarius in the 6th century, the city was renamed " Justinianopolis " (after Emperor Justinian I ).

In the 7th century which occurred Arab conquest of the city by Uqba ibn Nafi . It was only re-founded by the Aghlabids around 800 under the name Sūsa mentioned at the beginning and experienced a rapid rise as the port of Kairouan and the starting point for the Arab conquest of Sicily . During the time of the Aghlabids, the Ribāt was built in 821, the fortress ( kasbah ) in 844 and the main mosque in 851. In the spring of 946 the city was besieged for several months by the Ibadite insurgent Abū Yazīd Machlad ibn Kaidād .

In the 12th century, Sousse was occupied by the Normans . During the Turkish rule, like other port cities, it was a base for the corsairs who operated from the Maghrebian barbarian states . This resulted in attacks by the Spanish , French and Venetians , which led to the city's gradual decline. The ascent only took place in the French colonial period from 1881 with the construction of the new town and the port, which mainly served the export of phosphate and was only temporarily interrupted during the Second World War .

On June 26, 2015, at least 39 people, including Germans, were killed in the attack in Port El-Kantaoui in 2015 on a hotel complex around ten kilometers north of the city.

Cityscape

The medina (old town) of Sousse dates back to the 9th century and is surrounded by a 2.25 kilometer long city wall. It belongs since 1988 to the World Heritage of UNESCO .

The port, which was laid out in 1899, extends on the eastern edge of the medina. To the north of this is the new town laid out by the French. Tourist hotels are lined up on the beach in a northerly direction along a promenade. This part of the city along the coast is called - in the Tunisian dialect - Bou Dschaʿfar. The name goes back to a little-known scholar from the city of Abū Jaʿfar Aḥmad ibn Saʿdūn al-Urbusī, who died in Sousse in 935 and was buried in the Qubbat ar-Raml cemetery (dome on the sand) on the coast.

Buildings

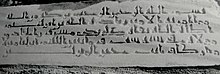

Ribat

The Ribāt was founded under the Aghlabids in 821, its original name was Ḥiṣn Sūsa (The Fortress of Sousse) and which gradually lost its military function after the city walls were built in 859 AD. The facility served as a storage facility for the neighboring arsenal. The founding inscription on a marble plaque is inserted above the gate to the watchtower.

“In the name of the merciful and gracious God. (The) blessing comes from God (alone). This is what the Emir Ziyādat Allah ibn Ibrāhīm ordered through his servant and freedman Masrūr in the year 206, God grant him long life. Lord God, 'grant me a blessed place to stay! You can best find accommodation. '"

The last sentence - except for the first word Allāhumma - corresponds to Sura 23 , verse 29.

In addition to a small mosque on the upper floor with a mihrāb , further rooms, magazines and the remains of an olive press can be seen in the basement. The imposing entrance, flanked by two Corinthian columns, is designed as a double gate and could be blocked from behind as well as from the front, thus preventing further access to the fortress.

The main mosque

The main mosque was built by the Aghlabid emir Abū ʾl-ʿAbbās Muhammad I in 236 dH (between 850 and 851) according to the preserved building inscription that runs around the courtyard facades in Kufic style . The prayer room was extended by three naves between 894 and 897 in the direction of the Qibla wall. The dome pavilion on the north corner tower of the mosque, which serves as a minaret, is a later addition, but - contrary to Creswell's view - dates from the first half of the 10th century. This dome can already be found in the biography of the judge of Sousse al-Hasan b. Nasr al-Susî, who died in 952, mentioned as follows:

“At the time of the fair, when the Kairouans came to the Ribat (to Sousse), he (the judge) used to sit in the great mosque of Sousse under the dome (qubba) from which people are called to prayer and which open to the gates Whenever he saw a man coming who had a boy with him, he let him come. If the boy was with his father or some other relative, he let him go. But when he (the judge) suspected him (of homosexuality), he prevented him from freely disposing of the boy. "

Bou Fatata Mosque

The Bou Fatata Mosque مسجد بو فتاتة / masǧid Bū Fatāta is the city's oldest mosque. It is located near the south gate, on the edge of the markets, and has a musallā in front . The oldest sacred inscription in Kufic style in North Africa on the outer wall of the complex is worth seeing. According to tradition, this small mosque with a side length of only eight meters dates from the time of the Aghlabid ruler Abū ʿIqāl al-Aghlab ibn Ibrāhīm (ruled between 838 and 841) and was named after his freedman Fatata. The remarkably small dimensions of this mosque, which was built twenty years before the main mosque was built, suggest that the city had a low population at the time. The horseshoe arch structures inside are comparable to the prayer room layout of the later main mosque.

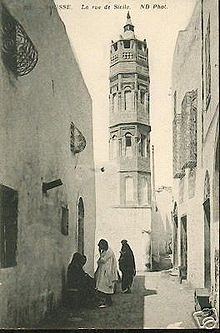

The Koran school az-Zaqqāq

The "Madrasa az-Zaqqāqiya" is located near the main mosque, in Rue de la Sicile, where the residential districts of the old town merge into the markets. المدرسة الزقاقية / al-madrasa az-Zaqqāqiya , whose own mosque is flanked by a Turkish-style minaret. According to local traditions, the name of this former school goes back to the Moroccan scholar ʿAlī ibn Qāsim az-Zaqqāq († 1506 in Fez ). However, it is likely that the name is associated with the little-known local scholar Abū Dscha'far Aḥmad az-Zaqqāq from the late 9th century. The pupils who studied grammar and rhetoric in addition to the Koran were housed in the small wings of the school. Originally it was probably a private house that was converted into a school under the Hafsiden .

This building probably originally goes back to an Aghlabid foundation and is then under the Sanhajah , i.e. H. expanded during the Zirid rule in Ifrīqiya ; because in one of the rooms there is a grave with an inscription from the 11th century.

Kasbah

The fortress ( Kasbah ) dates back to 844 and is located at the highest point in the old town. In the year 853 the 30 meter high lighthouse Khalaf al-Fatâ - named after a eunuch of the aghlabid ruler Ziyadat Allah I - was added. Today the kasbah houses the Sousse Archaeological Museum , which exhibits Punic , Roman and early Christian exhibits.

Parts of the kasbah formed the backdrop of the city of Jerusalem in Franco Zeffirelli's 1977 film adaptation of the Bible, Jesus of Nazareth .

as-Sufra

In the middle of the markets (al-aswāq) of the old town stands a small building with an imposing dome and a front courtyard, which is now known as as-Sufra (actually: "dining table"). The city's largest cistern originally stood here , the foundations of which with large vaults date back to Roman times . Under the Aghlabids, the complex initially served as a prison. According to local historians in North Africa, the cistern, which is still partially preserved today, was built under the Emir Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm II , who ruled from 875 to 902, who visited the city several times to follow the construction work on site. At the request of one of the city's scholars, he abolished the prison, had the old vaults renovated and a cistern set up for the population. The cistern was fed with rainwater from two collecting basins near Sousse - today al-Moureddin. The expansion of the city's main mosque also took place at the same time.

Today the renovated facility serves as a museum with the adjoining Café al-Qubba ("The Café on the Dome").

Economy and tourism

As in antiquity and in the Middle Ages , Sousses' economic importance today is mainly based on its role as an export port. In addition, the textile and food processing industries have settled in Sousse . Tourism has established itself as an important economic factor. In the north of Sousse there are hotels with a capacity of 40,000 beds in the beach area.

In November 2019, a modern shopping center (Mall of Sousse) was opened a few kilometers outside Sousse in the suburb Kalâa Kebira .

traffic

Sousse train station is on the main SNCFT line from Tunis to Sfax , also known as the Ligne de la Côte. Several trains run daily to Gabès and Tunis. The city has a Louage station. The taxis run daily to Tunis, Monastir , Kairouan , Sfax-Gabès, Kasserine , Gafsa and the surrounding settlements. There are also direct connections to Tripoli , Libya .

The SNCFT also operates a local train, the so-called Métro du Sahel . It connects Sousse with Mahdia via Skanes and Monastir . The starting point of the metro is at the southern port at the old city gate Bab Djedid.

From 1882 to 1896, the Chemin de fer Decauville de Sousse à Kairouan , built by the French within 3½ months on a Roman road , was in operation with a gauge of 600 mm.

Sousse can be reached both from Monastir Airport, ten kilometers away, and from Enfidha-Hammamet Airport, around 30 kilometers away .

Town twinning

-

Thiès , Senegal since 1965

Thiès , Senegal since 1965 -

Ljubljana , Slovenia since 1967

Ljubljana , Slovenia since 1967 -

Poděbrady , Czech Republic since 1969

Poděbrady , Czech Republic since 1969 -

Braunschweig , Germany since 1980

Braunschweig , Germany since 1980 -

Marrakech , Morocco since 1982

Marrakech , Morocco since 1982 -

Constantine , Algeria since 1984

Constantine , Algeria since 1984 -

Atar , Mauritania since 1989

Atar , Mauritania since 1989 -

Boulogne-Billancourt , France since 1993

Boulogne-Billancourt , France since 1993 -

Miami , United States since 1994

Miami , United States since 1994 -

Salalah , Oman since 1994

Salalah , Oman since 1994 -

Latakia , Syria since 1995

Latakia , Syria since 1995 -

Izmir , Turkey since 2006

Izmir , Turkey since 2006 -

Weihai , China since 2007

Weihai , China since 2007 -

Serpukhov Raion , Russia since 2007

Serpukhov Raion , Russia since 2007

sons and daughters of the town

- Oscar Ghez (1905–1998), entrepreneur, art collector and patron

- Hamed Karoui (1927–2020), politician and prime minister

- Luca Ronconi (1933–2015), Italian theater director

- Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali (1936–2019), politician and President of Tunisia

- Abdelmajid Chetali (* 1939), football player and coach

- Mohamed Ghannouchi (* 1941), politician

- Ahmed Bahaeddine Attia (1946–2007), film producer, film director and screenwriter

- Habib Essid (* 1949), economist and politician

- Hamadi Jebali (* 1949), engineer, journalist and politician

- Marcel Dadi (1951–1996), French guitarist

- Mohammed Sahbi Basly (* 1952), politician and diplomat

- Georges Fenech (* 1954), French politician and judge

- Dov Alfon (* 1961), Israeli journalist and writer

- Olfa Youssef (* 1964), university professor and author

- Ziad Jaziri (also Zied) (* 1978), football player, sports director

- Hamdi Kasraoui (* 1983), soccer goalkeeper

- Mejdi Traoui (* 1983), football player

- Mohamed Ali Nafkha (* 1986), football player

- Aymen Abdennour (* 1989), soccer player

- Haifa Guedri (* 1989), soccer player

See also

literature

- KAC Creswell: Early Muslim Architecture. Oxford 1932-1940.

- Hermann Dessau : Hadrumetum . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VII, 2, Stuttgart 1912, Col. 2178-2180.

- Alexandre Lézine: Sousse. Les monuments musulmans. Editions Ceres Productions. Tunis (no year).

- Alexandre Lézine: Le ribat de Sousse, suivi de notes sur le ribat de Monastir. Tunis 1956.

- Heinz Halm: News on buildings of the Alabids and Fatimids in Libya and Tunisia . In: Die Welt des Orients 23, 1992, pp. 129–157.

- Ḥasan Ḥusnī ʿAbdalwahhāb: Waraqāt ʿan al-ḥaḍāra al-ʿarabiyya bi-Ifrīqiya al-tūnisiyya (حسن حسني عبد الوهاب: ورقات عن الحضارة العربية بافريقية التونسية) Vol. II. Tunis 1981.

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Sousse city website (Arabic)

- Sousse, attractions Photos + info (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt 15-16

- ↑ Cf. Heinz Halm : Das Reich des Mahdi . CH Beck, Munich, 1991. p. 275.

- ^ Germans among the dead in the attack in Sousse. June 27, 2015, accessed June 27, 2015 .

- ↑ HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt, Vol. 2, pp. 61–62

- ↑ Heinz Halm (1992), p. 142

- ↑ HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt , Vol. 2, p. 26; Sulaimān Muṣṭafā Zbīss: Sūsa. Ǧauharat as-sāḥil (Sousse. The jewel of the coastal region). Tunis 1965. p. 21: with a reproduction of the Kufic script

- ↑ Alexandre Lézin: Sousse les monuments musulmans. Tunis (n.d.), pp. 35-40.

- ↑ Heinz Halm (1992), p. 141

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. 2, p. 247, No. 4

- ↑ Sulaiman Mustafa Zbīss: Susa. P. 22. Tunis 1965

- ↑ HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt, Vol. 2, pp. 65-66.

- ↑ HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt, Vol. 2, p. 66; Alexandre Lézin: Sousse les monuments musulmans . Tunis (no year). Pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Sulaiman Mustafa Zbīss Sousse. P. 28; HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt, Vol. 2, pp. 76-78.

- ↑ HH ʿAbdalwahhāb, Waraqāt, Vol. 2, pp. 63–65; Alexandre Lézine: Sousse. Les monuments musulmans. Pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Heinz Halm (1992), pp. 140-141.