Green March

As a Green March ( Arabic المسيرة الخضراء, DMG al-masīra al-ḫuḍrāʾ ) is a march of 350,000, mostly unarmed, organized by the state of Morocco in 1975 as part of the Western Sahara conflict . The march route leading from southern Morocco to Spain belonging colony Spanish Sahara , today's Western Sahara , and Spain should move to surrender the colony to Morocco. The term green comes from the color of Islam .

Starting position

prehistory

Western Sahara and Mauritania are the colonial delimitations of a desert and savannah area, traditionally called trab el-beidan ("land of the whites", i.e. the Bidhan ), which extends from the Wadi Draa in southern Morocco to the Senegal River . The various Sahrawi tribes in Western Sahara are sub-groups of the Bidhans with their language and culture. Their habitat on the Atlantic coast had belonged to the Spanish sphere of influence since the last third of the 19th century. In 1884 a private company founded the trading post Villa Cisneros (today Ad-Dakhla ) as the first settlement on the coast . In June 1900, Spain and France laid down the borders for the colony Río de Oro in the south of what is now Western Sahara. The borders of the northern part, Saguia el Hamra , were shifted several times in further negotiations with France between 1902 and 1912. The Spanish Sahara colony was created in 1924 from the union of the two areas.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Spanish traders and military were only present in a few places on the coast and hardly penetrated into the country. The Sahrawis defended themselves in the interior against the colonial regime with raids (Ghazzi) on trade caravans. Effective control of the entire area was not exercised by the Spaniards until 1930, when they had to rely on the support of French troops for their “pacification campaigns”. In 1934 the Spaniards set up their first military base in Smara , in the northern center of the country.

In February 1956 Spain was asked by the United Nations (UN) to submit a report on the legal situation of its colonies. With an administrative trick, the Franco regime then changed the status of its colonies in northwest Africa and made them Spanish provinces. The UN passed the first resolution against these overseas provinces, whose colonial character was clearly recognizable, in December 1965. Only Portugal then voted on the side of Spain.

Anti-colonial resistance remained low until the 1950s. In 1956, a liberation army was established against the government of the Moroccan King Mohammed V in the remote south of Morocco . This was increasingly joined by Sahrawis and carried out numerous attacks on targets in Western Sahara. In a joint Operation Ouragan in February 1958 - there were 9,000 Spanish soldiers and 60 aircraft, 5,000 soldiers and 70 aircraft on the French side - the Sahrawi guerrillas were defeated. In 1959 they stopped their attacks. In the early 1960s, those involved concentrated on a peaceful solution.

At the request of Morocco and Mauritania, the Western Sahara question was the subject of negotiation in 1963 by the decolonization committee of the UN General Assembly . With resolution 2072 of December 16, 1965, the Spanish government under General Franco was asked to decolonize the Western Sahara and to grant the population the right to self-determination .

However, Morocco made its own claims to the area. As early as 1957, the Moroccan government had set up a department for Saharan affairs . In 1963 a Ministry for the Affairs of Mauritania and the Spanish Sahara was set up .

However, contrary to the global trend towards decolonization , Spain expanded the administration of the colony and made efforts to promote economic development. In 1962, for example, the exploitation of the phosphate deposits in Bou Craa began .

In 1967, in response to increasing international pressure, Spain declared itself ready in principle to hold a referendum in Western Sahara on the question of the future status of the area. However, actual implementation has been delayed. In 1973 the Western Saharan liberation movement POLISARIO was founded , which took up an armed struggle against the Spanish colonial power. In the same year the Franco government offered the tribal assembly a statute of autonomy. The aim of Spanish politics was to maintain the greatest possible influence on the Western Sahara and to prevent an annexation to Morocco.

In 1974 Morocco’s King Hassan II refrained from calling for a referendum and called for the area to be annexed to his country without any referendum. On August 21, 1974, Spain informed the UN that it intended to hold the referendum in the first half of 1975. In addition to diplomatic efforts, Morocco then moved troops to the border area with Western Sahara. Spain also increased its military presence, both in the colony and in the nearby Canary Islands .

Probably during an Arab summit in Rabat in October 1974, Morocco and Mauritania reached a secret agreement according to which Western Sahara should be divided between the two states. Political observers suspect that a decision to take the area by force, if necessary, was also made during this period.

On the initiative of Morocco and Mauritania, the United Nations then passed resolution 3292 , in which the International Court of Justice was asked for an opinion. Spain has been asked to postpone the referendum.

The report came to the conclusion that the people of Western Sahara should decide for themselves about the status and that the area does not already belong to the territory of Morocco or Mauritania.

Domestic political situations

Domestically, the Moroccan government and Hassan II were also under considerable pressure because of the Western Sahara question. The opposition accused Hassan II of acting too hesitantly and criticized a lack of initiative and willingness to fight. The Green March therefore made it possible for the Moroccan government to take the initiative in domestic politics, to gather the political forces behind a national idea and to weaken the opposition.

In Spain the dictator General Franco was seriously ill. The end of his reign was looming, so that the domestic political situation in Spain was marked by instability. The powers as head of state had just been transferred to the designated successor Juan Carlos . Franco died on November 20, 1975, just days after the march.

The march

preparation

Announcement and planning

With a declaration by King Hassan II on October 16, 1975, Morocco attempted to interpret the opinion of the International Court of Justice in its favor. The report had established legal ties between Morocco and Western Sahara in the past . Hassan II derived from this a dependency of the area and took the position that according to Islamic law Morocco had a claim to the Western Sahara. In this declaration, Hassan II announced the implementation of a peace march (Massirah) of 350,000 unarmed people from Morocco to Western Sahara. The march was scheduled to begin on October 24, 1975.

The plan for the march came from Hassan II himself. The Moroccan government had been making preparations for the march for about two months, in strictest secrecy. The king announced that there were plans to rally 350,000 unarmed people at Tarfaya in southern Morocco, near the border with the Spanish Sahara. With him as king at the head, the procession should cross the border to El Aaiún , the capital of Western Sahara, and thus achieve recognition of the Moroccan claim. The march was then supposed to cover the approximately 160 kilometers long distance from the border to El Aaiun and back within 15 days. All provinces of Morocco were called upon to take part in the march with an already precisely calculated contingent.

Reaction of the international community

The international community was surprised at the unusual announcement. The states of the Arab League assessed the situation differently. Eleven of the twenty member states welcomed the project, including Egypt and Saudi Arabia , and some offered support. Seven members, including Syria and Iraq , did not position themselves clearly. The project met with clear rejection from Algeria and the socialist countries. Above all, the Soviet Union and the GDR expressed their disapproval here. The USA and France were neutral .

Mauritania welcomed the announcement. The request from Morocco to initiate a similar action from Mauritanian territory, however, was not followed.

Spain expressed concern about the announcement and turned to the UN Security Council . After two days of deliberations, the latter passed resolution 377 on October 22nd, which , however, contained no concrete measures and only called on the UN Secretary-General to hold talks with those involved and to report to the Security Council. Already seriously ill, but at the time still in charge of Spanish official duties, General Franco sent José Solis Ruiz to Rabat to negotiate with Hassan II. As a result, it was agreed to postpone the start of the march. Morocco undertook to send a special envoy to Madrid to continue negotiations.

While a first group of 20,000 people from the Moroccan province of Ksar-Es-Souk had set out for Tarfaya, Spain began to evacuate the affected areas from the civilian population with the Operación golondrina .

negotiations

As agreed with Spain, Morocco announced on October 24th that the march would not take place until October 28th. On the same day, the Moroccan Foreign Minister Ahmed Laraki arrived in Madrid for further talks. His Spanish negotiating partners were Prime Minister Carlos Arias Navarro and Foreign Minister Pedro Cortina Mauri . The content of the conversation was secret. The negotiations were initially interrupted on October 26th.

Laraki traveled to briefings with Hassan II and the Mauritanian President Moktar Ould Daddah before the talks resumed on October 28. A delegation from Mauritania, the commander in chief of the Moroccan military in southern Morocco and the chairman of the Moroccan phosphate company Office Chérifien des Phosphates , Mohammed Karim Lamrani , also took part in these talks .

Due to the secrecy, the content and the results of the negotiations were not disclosed. However, rumors quickly spread that it had been agreed to give in to Morocco's demands and cede Western Sahara to Morocco. In fulfillment of the Moroccan / Mauritanian secret agreement, however, Morocco is prepared to forego the southern part of Western Sahara in favor of Mauritania. Spain should be given economic and strategic advantages. In order to enable Morocco to save face in the face of the announced march, it was also agreed that the march could penetrate the Western Sahara, but only for 48 hours and with a maximum depth of 10 km. However, it is a matter of dispute whether this was actually agreed. There are some indications that Spain did not approve of the border crossing and that its strategy tried to separate the decolonization of Western Sahara, which was unavoidable from the Spanish point of view, from the negotiating pressure built up by the march.

During the same period, the UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim tried to find ways of a peaceful solution in accordance with Resolution 377 and to highlight them in a report to the UN Security Council. The report, which gave the UN a major role in the search for a permanent solution, was later referred to as the Waldheim Plan .

Algeria was concerned about this development, the tripartite talks in Madrid and the more wait-and-see attitude of the UN. It protested against the Spanish government and transferred troops to the border between Algeria and Western Sahara.

In this situation there was a significant deterioration in General Franco's health. Prince Juan Carlos was given the office of head of state. The Spanish attitude now changed significantly. The continuation of negotiations scheduled for October 30th has been canceled. Juan Carlos surprisingly arrived in El Aaiun for a visit by the Spanish troops and the Spanish UN ambassador Fernando Arias Salgado told the UN Security Council on November 2 that Spain would defend the border with Western Sahara by force if necessary. The Western Saharan independence movement POLISARIO called on Spain to fulfill its duty as a protective power and, if necessary, to protect Western Sahara from the intrusion of marchers with force.

Morocco responded to this change with extensive diplomatic activities. There were talks between Ahmed Osman and Juan Carlos and Arias Navarro in Madrid. On November 3, the talks were broken off as a failure. Envoys to the Soviet Union were also sent to Moscow and Algeria. For Morocco it was not clear how Spain would react to the invasion of the Green March participants. Hassan II hesitated with the order to leave.

recruitment

The Moroccan government set up recruitment centers to recruit march participants. Specially appointed people recruited participants all over the country, even in the smallest villages. After just three days, the recruitment agencies had registered 524,000 participants. Moroccan sources even spoke of 695,902 registered persons. In addition to a certain pressure from the public authorities, the high number of registered persons was also attributed to a national euphoria triggered in the country. In the end, however, there were also 42,500 Moroccan officials among the participants. The large number of people available gave the authorities a certain choice. Students were so completely excluded. The urban population, judged to be less loyal to the king, was underrepresented in relation to the rural population. Daily allowances were also paid to the participants. Of the estimated 350,000 people involved in the march, approximately 50,000 were women.

logistics

The logistical effort involved in transporting such large numbers of people to the sparsely populated border area was enormous. 7,813 trucks and buses, some of which were confiscated, brought the participants from Marrakech , where they had arrived on special trains that ran for several weeks, to Tarfaya. A tent city with 22,000 tents had been erected there over an area of 70 km². 17,260 tons of food were in warehouses in Tarfaya, Guelmim and Tan-Tan . 23,000 tons of water and 2,590 tons of gasoline were flown in with Hercules 130 planes. 470 doctors and 230 ambulances were provided to take care of the participants. Many representatives of the international press had also gathered in Tarfaya. According to later Moroccan data, the total cost of the march was 8 million British pounds , other estimates put it at 300 million US dollars . In addition to a national Moroccan tender, the costs were also financed by foreign support, particularly from Saudi Arabia.

Moroccan military

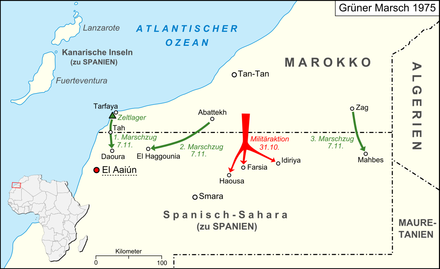

Already on October 31, 1975, well before the actual start of the march, Moroccan troops marched into the remote north-eastern Western Sahara, unnoticed by the world public. They advanced on Farsia , Haousa and Idiriya , which had been evacuated by the Spanish military. There was fighting with units of the Western Saharan liberation movement POLISARIO. The strategic goal of this approach was to forestall a possible entry of Algerian troops and to bind the units of the POLISARIO in order to prevent their access to the planned march themselves.

In total, Morocco had twelve companies and 20 battalions of infantry and artillery and thus about 8,000 to 12,000 men stationed near the borders with Western Sahara and Algeria. The tank units stationed at Tan-Tan were seen as particularly powerful .

In the march itself there were around 30,000 armed soldiers from the Moroccan army . This not inconsiderable number, which contradicts the officially peaceful character of the march, later gave rise to speculation that the unarmed participants merely served to camouflage this army. In actual fact, however, the military and police units advancing into Western Sahara with the march limited themselves to maintaining the internal order of the march.

course

Start on November 6th

After several postponements, the march began on November 6, 1975, after a radio address by Hassan II announced on the evening of November 5. A few hours earlier, the Spanish military governor of the Spanish Sahara, General Gómez de Salazar , had made it clear in a press conference that the Spanish military would defend the area. When asked whether there was an agreement that the march would be tolerated up to a line of defense within Western Sahara, Salazar said that he was not aware of such an agreement.

There had been a lot of activity all night in the camp at Tarfaya. The marchers were taken by truck over 36 km from Tarfaya to the south to near the border. At 10:00 a.m., large crowds had gathered on the road from Tarfaya to the Tah border post . At 10:30 a.m., a first column of 40,000 people began their way south. At the head of the procession were Moroccan Prime Minister Ahmed Osman and other members of the cabinet. An iron triumphal arch adorned with a picture of Hassan II and Moroccan flags had been erected over the street in Moroccan territory , through which Osman passed. He said: "We will march ten kilometers and then see." Behind this point were other well-known Moroccan personalities and foreign participants. The flags of Gabon , Jordan , Qatar , Kuwait , Oman , Saudi Arabia and Sudan were carried. Reports that a US flag was also carried may be traced back to a vehicle of the US press that carried such a flag.

Osman himself then opened the barrier at the border. Then 20,000 participants each from the Moroccan provinces of Ouarzazate and Ksar-es-Souk ran at the Spanish border post Tah, 800 meters away, holding the Koran . The marchers bypassed the post itself. However, a flag of Morocco was hoisted . The Spanish police had already vacated the post a few days earlier.

The people at the head of the march knelt and rubbed their faces with the earth of Western Sahara.

The front of the march was several kilometers wide. At 11:15 a.m., the train passed the official figures. The calls Allah is Great and the Sahara is also repeated in Moroccan language .

At 1:00 p.m. the head of the marching column had advanced ten kilometers into Western Saharan territory without encountering any resistance. Planes and helicopters, including four Spanish ones, were constantly circling over the march. At around 1:30 p.m., the column stopped twelve kilometers south of Tah and only a few meters from the village of Daoura . There was a Spanish line of defense here. The marchers set up a rest area along the defense line over a width of four kilometers. 40,000 to 50,000 march participants then stayed there. A group of around 2,000 people tried to break through the Spanish defense lines during the night, but were forcibly prevented from doing so by units of the marching Moroccan gendarmerie.

diplomacy

The UN Security Council had already met for a closed session on the night of November 5th to 6th. The Moroccan ambassador emphasized that the march only had a symbolic function. The representatives of Spain and Algeria rejected this view. Although the Moroccan approach was viewed very critically in the Security Council, the USA and France prevented a condemnation of the invasion. The Security Council only authorized its President Yakov Alexandrowitsch Malik (Soviet Union) Hassan II to request to end the march immediately. The king replied early in the morning, but only reiterated that the march was merely peaceful.

While the marching column was still standing in front of Hassi-Ad-Dawra and other marching participants were arriving, attempts were made to resolve the situation through diplomatic channels. In response to a Moroccan initiative on 6 November 6 p.m., Spain responded by saying that it would only be willing to resume negotiations on the status of the area if the marching columns withdrew from Western Sahara. Morocco agreed on the condition that Spain immediately send a negotiating delegation to Agadir and that the Waldheim Plan, which is still being drawn up at the UN, would not play a role in the negotiations. In fact, Spain agreed and immediately dispatched the Presidential Minister Antonio Carro Martínez to Agadir.

The UN Security Council met again on November 6th and was able to agree on the somewhat clearer Resolution 380 . In it he noted that, contrary to the previous request, Morocco had continued the march.

Continued on November 7th

In the meantime, however, Morocco's presence in Western Sahara had been further strengthened. On the night of November 6th to 7th, 100,000 participants were brought to the border by truck via Abattekh , who then crossed the border on foot. This second march moved six kilometers into Western Saharan territory and set up a second camp north of El Haggounia . On November 7th, a third group advanced through Zag towards Mahbes . This third group was to encircle large parts of the Spanish military.

Spain responded by tightening military preparations and moving additional elite units to the area. Paratroopers and the 93rd artillery regiment arrived on November 8th . On the same day, the Spanish units received the order to shoot unarmed marchers in an emergency.

Negotiation in Agadir

On November 8th, the Spanish Presidential Minister Antonio Carro Martinez and the Moroccan King Hassan II met in Agadir for negotiations that quickly came to a conclusion. Morocco moved away from the previous demand for the immediate cession of Western Sahara. The order of the march retreat made Hassan II dependent on the fact that the negotiations originally conducted between Spain, Morocco and Mauritania would be resumed. Spain responded to this. The Moroccan compliance was explained by the difficult situation that had arisen for Morocco. On the one hand, international pressure increased, on the other hand, a peaceful entry into El Aaiun could not be achieved against a possible Spanish military resistance.

March back

On November 9, 1975, Hassan II addressed the Moroccan population and march participants in a radio broadcast. To the surprise of the march participants who were expecting an attempt to move on to the Western Saharan capital, Hassan II declared that the march had reached its destination. The other results should be sought in other ways.

Indeed, on November 10th, the marchers turned around and went back to Tarfaya. The Moroccan government announced that the marchers in their camp in Tarfaya would wait for further developments and would invade Western Sahara again if the negotiations failed.

Result

The negotiations forced by Morocco were to take place in Madrid a few days later. The government of Algeria, which spoke out clearly against the annexation of Western Sahara to Morocco, intervened on November 10th with the Mauritanian President Moktar Ould Daddah. At a meeting between Algerian President Houari Boumedienne and Daddah in Bechar , Boumediene tried to prevent Mauritania from cooperating with Morocco.

During the negotiations in Madrid, however, Spain, Morocco and Mauritania reached an agreement very quickly without the Algerian concerns or the Waldheim plan that the UN Secretary-General had put forward in the meantime. According to the joint communiqué passed on November 14, Spain was to cede Western Sahara to Mauritania and Morocco by February 28, 1976. The Spanish parliament approved the decolonization of the Spanish Sahara with 345 votes in favor, 4 against and 4 abstentions.

On November 18, 1975, Hassan II made another address to the public and ordered the marchers who were still waiting in Tarfaya to return to their hometowns. A not inconsiderable number of the march participants had not even been deployed during the actual march and had not crossed the border to Western Sahara.

Further development

In February 1976 the last Spanish soldiers left Western Sahara. Regular Moroccan troops quickly moved into Western Sahara and occupied Smara on November 27, 1975 . On December 11th, the Moroccan army entered the capital El Aaiun. In the south of Western Sahara, Mauritania occupied La Gouira on December 20, 1975 .

The UN General Assembly passed resolutions 3458 A and 3458 B , which, however, continued to demand the possibility of self-determination for the people of Western Sahara.

A tribal assembly Djamaa that met on February 26, 1976 in El Aaiun , which was occupied by Moroccan people and was formed during colonial times, unanimously approved the tripartite agreement , in which Morocco and Mauritania saw sufficient self-determination.

However, on the night of February 27th to 28th, the Western Saharan resistance movement POLISARIO proclaimed a Democratic Arab Republic of the Sahara , which is still recognized by many states as the legitimate representative of Western Sahara. The Polisario fought a long war against Morocco and Mauritania, as a result of which Mauritania withdrew from the southern part, which was then occupied by Morocco. There is now a truce. Morocco controls around 70 percent of Western Sahara, including all of the larger cities.

The status of Western Sahara is still unclear.

Classification of the Green March under international law

The international legal character of the Green March is controversial and is judged differently depending on the respective political point of view.

From a Moroccan point of view, the march was justified by a state emergency . Morocco stated that the area belonged to the Sherif Empire until the colonization by Spain . Although the later Morocco has lost territorial sovereignty, it has not lost its sovereignty to Spain. Morocco had merely confirmed and enforced its existing claims through the march.

After the Spanish position, the area has been abandoned late 19th century, so that legally one occupation by Spain adjusted.

The opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) came to the conclusion that the area at the time of colonization by Spain was at least not ownerless ( terra nullius ) . While the ICJ supported the Moroccan view in this respect, it did not follow the view of Morocco that the area was under the sovereignty of the Sherif Empire at the time of the occupation by Spain. Although there were legal relationships with some of the nomadic tribes, there was no evidence of state activity in what would later become Morocco.

The Western Saharan independence movement Polisario took the position that Western Sahara was not under Moroccan sovereignty and that Spain was merely a protecting power. This view, according to which neither Morocco nor Spain held the territorial sovereignty of Western Sahara at the time of the march's invasion and could dispose of it, is also the result of considerations of international law by European authors. As far as one follows this view, the advance of the Green March into the area of Western Sahara would not have been justified under international law and would therefore have to be assessed as an intervention and violation of the prohibition of violence , despite the majority of the march participants being unarmed .

literature

- Mourad Kusserow : Destiny Agadir - Maghrebian Adventure , Verlag Donata Kinzelbach, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-942490-07-8 . Kusserow, who had already participated in the Algerian War of Liberation , took part in the Green March as editor of Deutsche Welle . He took an unreservedly pro-Moroccan position.

- Abigail Bymann: The march On the Spanish Sahara: A Test of Internat. Law , in the Denver Journal of Intern. Law + Policy , Volume 6, 1976, pp. 95-121 (English).

- Ursel Clausen: The conflict over the Western Sahara , in work from the Institute for Africa Customers in the Association of the Foundation of German Overseas Institutes , Hamburg 1978.

- Muhammad Maradyi: La marche verte ou la philosophie de Hassan II , Paris 1977 (French)

- Abdallah Stouky: La Marche verte , Paris 1979 (French).

- Werner von Tabouillot: The Green March in the Light of International Law , Munich 1990, ISBN 3-88259-724-0 .

- Jerome B. Weiner: The Green March in Historical Perspective , in The Middle East Journal , vol. XXX III., 1979, pp. 20-33 (English).

- CG White: The Green March , in Army Quarterly and Defense Journal 106 , Julie 1976, pp. 351-358.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tony Hodges: Western Sahara. The Roots of a Desert War. Lawrence Hill Company, Westport (Connecticut) 1983, p. 135

- ↑ Hodges, p. 80

- ↑ a b by Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 27

- ↑ Expert opinion from October 16, 1975 ( Memento of the original from February 1, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. PDF, 8.5 MB

- ↑ from Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 30

- ↑ from Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 34 ff.

- ^ Von Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 193

- ↑ a b by Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 24

- ↑ Ingeborg Lehmann, Morocco , Ostfildern 2001, ISBN 3-87504-412-6 , p. 405

- ↑ a b by Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 26

- ^ From Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 53

- ↑ from Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 52

- ^ From Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 39

- ↑ a b c by Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 40

- ↑ a b by Tabouillot, The Green March, p. 45

- ↑ from Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 46

- ↑ so also Werner von Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 194

- ↑ from Tabouillot, The Green March, p. 134

- ^ From Tabouillot, Der Grüne Marsch, p. 113