Smara

Coordinates: 26 ° 44 ′ N , 11 ° 40 ′ W Smara , Arabic السمارة, DMG as-Samāra , also as-Smara, Semara, is the capital of the Es Semara Province in the north of Western Sahara . It is the only major city inland of the territory claimed and administered by Morocco . Founded in the anti-colonial liberation struggle around 1900, Smara became the religious center of the Sahrawis and, after the occupation by Moroccan troops in 1975, primarily a large military camp, whose economic power ensures a steady increase in population. According to the 2014 census, the city had 57,035 residents.

Smara is the name of one of the four tent camps (wilayas) in the western Algerian province of Tindouf , to which Sahrawis had to flee from 1975 during the war of independence between the Moroccan military and the Polisario .

location

The area around Smara, like the country as a whole, consists of almost vegetation-free, solid stone and sand desert with only a few places where potable groundwater close to the ground can be drilled. Groundwater is available in several places along the Saguia el Hamra , an east-west wadis . Smara is located in the middle of this dry valley, eight kilometers south of the only temporarily water-bearing main river and about 170 kilometers as the crow flies before it flows into the Atlantic near El Aaiún . The only tree in the dry valley around Smara and only found here is Acacia raddiana, a subspecies of the umbrella acacia ( hassania : talkha ), which can be seen for several kilometers with its trunk twisted by the wind.

By road, the distance to El Aaiún is 240 kilometers and to Tan-Tan , the nearest town in the north on Moroccan territory, 245 kilometers.

history

The first settlement was from 1869 a rest area at a crossroads of caravan routes between the oases in southern Morocco and Mauritania . There was enough water and grazing land here.

From 1873 or 1884, the Muslim scholar Mā al-ʿAinin (1830-1910), who led the nomadic tribes in the war against the French colonial rulers as partisan leader, lived there for a time. The sheikh , who came from the Marabout caste , declared himself a descendant of Moulay Idris and thus achieved the highest religious status of the Chorfa descent ( Moroccan Arabic for Sherif ). In 1887 he received the title of caliph and arms for the liberation struggle from the Moroccan Sultan Hassan I. Spaniards were only present in small settlements on the coast at that time. When the French began to advance inland, many Sahrawi nomads gathered around Mā al-ʿAinin from 1890 onwards . In 1895 he declared holy war ( jihad ) and withdrew from his base east of Ad-Dakhla to the strategically more favorable caravan base further inland. In 1898 the construction of a Ribāt began on his behalf in Smara . It was the only city in the Western Sahara that was not initiated by the colonial powers. The money came from the Sultan's successor, the young Abd al-Aziz , over whom Mā al-ʿAinin had religious influence.

A fortress ( kasbah ) made of natural stone was built , including a mosque, a zawiya , palace buildings and caravanserais. For their construction, the several thousand nomads who worked with them received support from craftsmen from Morocco, the Mauritanian Adrar and the Canary Islands . The building material (wood and cement) also came from Morocco, it was shipped to Tarfaya by steamer and transported on with 1200 camels. The caravan traveled along the Saguia el Hamra for five days. The architects came from Morocco and Mauritania ; 200 date palms were brought from the same countries - the Wadi Draa and the Adrar region - for which 50 wells were dug. By 1902 the main part of the city was built.

In the library of Mā al-ʿAinin, among other things, about 300 writings of the sheikh were kept. Smara developed into the cultural center of the Sahrawis; The idea of a “holy city” lives on from this time. When the military inferiority of Mā al-ʿAinin became apparent and in 1909 the support of the Moroccan sultan failed to materialize, he declared himself the god-chosen sultan and in 1910 moved with his army towards Fez . On the way he was defeated by French troops and died that same year. In 1913, the city was practically deserted when it, and with it the mosque and library, were largely destroyed in an excursion by French troops under Colonel Mouret. It was revenge for a Sahrawi raid (ghazzi) against the French. The vandalism at the holy site was viewed as sacrilege by the locals. The anti-colonial resistance was carried on by Mā al-ʿAinin's son el-Hiba and others of his descendants, who de facto controlled the country. Violent "pacification" actions by French and Spanish troops in the Spanish colonial area from 1930 onwards led to the permanent occupation of the still deserted city in 1934. The Spaniards set up a military base and an administration.

The first European to visit the city of Smara, which has long been forbidden for Christians, was Michel Vieuchange in 1930 . He died shortly afterwards of the consequences of his hardship-filled journey.

The destroyed buildings were partially rebuilt later. In 1954 the Spaniards restored the dome of the central rooms of Mā al-ʿAinin. In 1957 the Spaniards had to withdraw from the city because of a growing threat from insurgents of the Liberation Army of the South (ALS). In February 1958, it was reoccupied by a Franco-Spanish army as part of Operation Ouragan. In the 1960s, Smara was connected to El Aaiún by an asphalt road. The establishment of an administration and the construction of houses attracted some new settlers, and by 1974 the city had grown to 7,295 inhabitants according to a census, more than ad-Dakhla at the same time.

After the Madrid Agreement, in which the Spaniards declared their withdrawal from their colony, Moroccan troops marched into the city on November 27, 1975. On April 14, 1976, the Moroccan and Mauritanian governments signed an agreement according to which Western Sahara was divided between the two countries. Smara became the capital of one of the three new Moroccan provinces. In Smara there were large demonstrations against the Moroccan presence, most of the residents fled 1975-1976 to refugee camps further east and to Algeria. From there, the Polisario Front launched attacks against the city, which, however, remained under Moroccan control.

Only in 1979 did the insurgents briefly succeed in conquering the Moroccan position. During their attack on October 6, the Polisario evacuated around 700 Sahrawis and took them to refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria . According to the DARS leadership on October 9, the attackers killed 1,269 Moroccan soldiers, captured 65 and destroyed 19 tanks, 83 trucks and 114 all-terrain vehicles. The Moroccan Ministry of Information said on October 8 that the attack had failed and that 375 of 5,000 Sahrawis had been killed. The next day, another 735 guerrillas were killed by the use of fighter planes. The figures evade independent verification. The result is that the Polisario must have been very well armed, that the Moroccan commander was killed in the fighting, the Sahrawis took several prisoners, while the Moroccans took no prisoners.

Since the completion of the first Moroccan Wall in 1981, which divides the Western Sahara into a Moroccan-administered part and a narrow strip of desert in the east under the control of the Polisario, there have been no further attacks on Smara. The few foreign visitors in the 1980s described Smara as a garrison town.

In 1999 the population was estimated at 33,000, the 2004 census showed 33,910 inhabitants. According to the 2014 census, 57,035 people live in the city and 66,014 people live in the province .

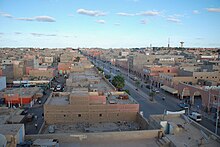

Cityscape

The streets are arranged according to a largely planar square pattern. Avenue Mohammed V is the main street running through the center from west to east. It runs on the western edge of the city past the largest military area - recognizable by long rows of pink domed roofs - outside to the airport, which is about two kilometers away, and initially parallel to the river bed further towards El Aaiún. Opposite the military area is the old Zawiya Mā al-ʿAinins, surrounded by a high wall, 200 meters to the north , whose qubba (place of worship / mausoleum of a Sufi saint) is particularly popular with women.

The old mosque was only preserved as a ruin with the outer walls and pillar surrounds until around 2008, since then it has been completely renovated. A rectangular inner courtyard is surrounded on all four sides by a double-row arcade corridor ( Riwaq ) , the flat roof of which rests on cruciform arches over octagonal pillars. The roof and pillars of the arches were made from concrete.

At right angles to Ave. Mohammed V leads the Ave. Hassan II to the south. In the evening this street becomes a pedestrian zone and promenade, which is livened up by shops and night market stalls. To the north this road ends at the bus station and taxi stand. In the vicinity there are six to eight simple hotel accommodations as well as market lanes where meat and vegetables are offered. The construction activity in the outdoor areas is related to the high number of police and military personnel who are not only in several barracks around and in the city, but are also omnipresent on the streets.

literature

- John Mercer: Spanish Sahara. George Allen & Unwin Ltd, London 1976

- Anthony G. Pazzanita, Tony Hodges: Historical Dictionary of Western Sahara. 2nd ed. The Scarecrow Press, Metuchen / New York / London 1994

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Creation of the refugee camp. Austrian Sahrawi Society

- ^ Walter Reichhold: Islamic Republic of Mauritania. Kurt Schröder, Bonn 1964, p. 36

- ^ Wolfgang Creyaufmüller: Nomad culture in the Western Sahara. The material culture of the Moors, their handicraft techniques and basic ornamental structures. Burgfried-Verlag, Hallein (Austria) 1983, p. 36

- ↑ Mercer, pp. 111f

- ↑ Mercer, p. 153

- ^ Virginia McLean Thompson, Richard Adloff: The Western Saharans. The Background to Conflict. Barnes & Noble, Totowa (New Jersey) 1980, p. 119

- ↑ Pazzanita, p. 410f

- ↑ Pazzanita, p 411

- ↑ Résultat du Recensement general de la population et de l'habitat 2004. Royaume du Maroc

- ^ Population Legale des Regions, Provinces, Prefectures, Municipalites, Arrondissements et Communes du Royaume. 2014 census data, Excel spreadsheet