Mongoose Park

Mungo Park (born September 11, 1771 in Foulshiels near Selkirk , Scotland ; † January / February 1806 near Bussa , Nigeria ) was a British traveler to Africa .

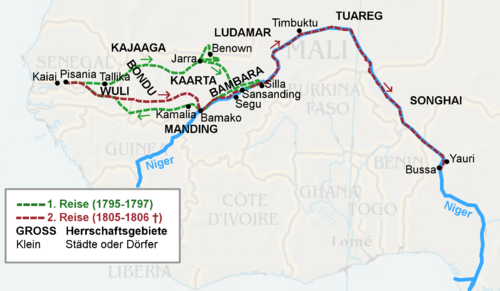

His two journeys (1795–1797 and 1805–1806) took him across the Gambia River to the Niger River . During his first trip on behalf of the African Association , he was captured but was able to escape penniless. He only survived with the help of an African. His travelogue Travels in the Interior of Africa , which was then published, was already a bestseller back then and is still considered a classic today. During his second trip to Niger, financed by the British government, he was killed in 1806.

Childhood, youth and education

Mungo Park was most likely born on September 11, 1771 on a farm in Foulshiels on the Yarrow Water River near Selkirk, Scottish Borders . That is the date as it is given in the baptismal register, although several older biographies and writings mention September 10th as the date of birth. He was the seventh of a total of 13 children. During his childhood, his fellow men mainly described him as “reserved” ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 22) - an assessment that he was often given later.

Park's parents were not wealthy as farmers, but they had enough money to provide their children with a good education. Mungo was brought up in "strict" Calvinism , and his parents urged him to become a clergyman . Nevertheless, in 1785, at the age of 14, he began his apprenticeship with the country doctor Thomas Anderson in Selkirk. During this three-year apprenticeship, he met his children Allison and Alexander. Allison later became his wife. Alexander, in turn, took part in the second expedition as Park's closest confidante and was killed in the process.

In the autumn of 1788 Park moved to Edinburgh to study anatomy and surgery at the university there until the summer of 1792 . However, botany fascinated him more than his medical field of study.

After completing his studies, Park went on botanical hikes through the Scottish Highlands with his brother-in-law James Dickson . Dickson, self-taught and recognized specialist in botany, had made a name for himself as a seed dealer at Covent Garden in London . He was a member of the Linnean Society of London , in which Sir Joseph Banks , the President of the Royal Society and himself an avid botanist, frequented. It must have been 1792 when Park became acquainted with the influential Joseph Banks while visiting his sister Margaret and brother-in-law James Dickson.

On the recommendation of Joseph Banks, Mungo Park became an assistant doctor on board the East Indiaman Worcester , who left Portsmouth on April 5, 1793 with a military escort for a year for Benkulen , Sumatra . The military escort was necessary because of the war between Great Britain and France. Upon his return in 1794, Park presented a lecture for the Linnean Society on eight small fish from the Sumatran coast , including unknown species. Park remained an extraordinary member of this learned society until his death ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 27).

On board the Worcester , he also learned basic astronomical knowledge and methods to determine latitude and longitude (Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 30). As a result, he recommended himself to the African Association as a future traveler. He was also a doctor, so he could treat himself and others if necessary, which the Association believes might earn him the respect of Africans. A skilled amateur botanist, he was able to provide descriptions and sketches of unknown species. In addition, during the trip to Sumatra, he had proven that he was able to cope with the warm, humid tropical climate.

His relationship with Joseph Banks now proved to be a stepping stone to quenching his thirst for fame and adventure through the African Association . Because, said Park in a letter to his brother-in-law Alexander before the first trip: "If I succeed, I will make a bigger name for myself than [a man?] Ever before!"

Political and geographical framework

Mungo Park's activities are framed by the coalition wars. In these, Great Britain fought alongside various allies from February 1, 1793 with small interruptions for 22 years against republican France. Although Park was originally from Scotland, he was always loyal to the UK. This is how his letters were addressed to Selkirk, Northern Britain , and not Scotland ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 16).

Another bracket was the independence of the USA from Great Britain . Britain was now looking for new colonies and markets. The largely unknown African continent has so far only been used for the lucrative slave business and aroused hopes for a second America .

However, “the map of its interior was still only a vast blank area” , which, from the point of view of the African Association, “must be regarded as a great disgrace for the present age.” Niger , in particular , were in at the end of the 18th century Europe does not know its source, its course or its mouth. There were only a few vague theories that were still based on the traditions of early geographers such as Herodotus , Al-Idrisi or Leo Africanus : It was assumed, for example, that the Niger could not be an independent river, but only another name for the westward one trading flowing Gambia or Senegal . Or, if that were inaccurate, that it passes eastward into the Nile or the Congo . Another popular theory was also advocated by James Rennell , the cartographer of the African Association , according to which the Niger flows east of Timbuktu into a large swamp or inland lake (Lit .: Sattin, 2003, p. 120; Müller, 1980, p. 235) .

Determining the location of the Niger was made more difficult by its unusual sickle shape: Rising just 300 km from the Atlantic Ocean, it flows in a north-easterly direction inland, then turns 90 degrees to the south-east after Timbuktu and finally flows into the Gulf of Guinea . It was also assumed that south of the Niger through all of Africa a mountain range called Mountains of the Moon or Mountains of Kong stretches, which the Niger could not possibly pass.

The first trip: the one-man expedition

On behalf of the African Association

After Park returned from Sumatra in early 1794 , he offered his service to the African Association , which was looking for a successor to Major Daniel Houghton . Houghton had been sent in 1790 to also explore the course of the Niger , but starved to death after an attack penniless in the Sahel zone .

On April 17, 1794, Park received a firm commitment from the African Association with the assistance of Joseph Banks . After Simon Lucas , John Ledyard and Daniel Houghton, he was the fourth Africa traveler to be selected by their five-member committee. From August 1, 1794 onwards, he was to receive 7½ shillings per day, and double that for two years after he set out from the Gambia into the interior of Africa. In addition, £ 200 was granted for his equipment. That is well over the 50 shillings a month he received as an assistant doctor on board the Worcester , but not too much for such a dangerous journey. The reason for this was that the African Association could only finance his trip through subscriptions from its members.

On April 21, 1794 he received formal instructions from his client, about which he later said in his travel report:

- “My instructions were clear and concise. I was assigned to advance to Niger after my arrival in Africa, either by Bambouk or by any other route which would prove to be the most suitable. That I should find out the direction and, if possible, the origin and end of this river. That I should go out of my way to visit the main villages and towns in its neighborhood, especially Tombuctoo and Houssa ; and that I should then be free to return to Europe either via the Gambia or on the route that would appear advisable to me under the circumstances of my situation and my prospects. "

His relatives were anything but enthusiastic, "because they were sure he would never come back," said his brother-in-law James Dickson. Park also knew about the danger of his journey:

- “Should I perish on my journey, I was ready to let my hopes and expectations drown with me; and should I succeed in making my compatriots more familiar with the geography of Africa and in opening up new sources of prosperity and new trade routes for their ambitions and diligence, I knew that I was in the hands of men of honor who would not fail to give the reward, who deserved my successful services in their eyes. "

In addition, Park had "the burning desire to examine the products of a country so little known and to get to know the way of life and the nature of the natives through personal experience" . Above all, however, he was fascinated by the idea of being considered the discoverer of Niger. In addition to clothes, a coat, a blanket and an umbrella, he had a pocket sextant, two compasses, a thermometer and two shotguns with him. He went dressed the same way as in Great Britain. Unlike later travelers like Friedrich Konrad Hornemann or Jean Louis Burckhardt , he did not try to hide his origins.

From the coast to Kaarta

On May 22, 1795, he sailed from Portsmouth on board the merchant ship Endeavor . A month later, Park went ashore in Jillifree on the Gambia, now Juffure . After traveling inland for a few days, he arrived on July 5, 1795 in Pisania, near today's Karantaba Tenda . Here he spent five months in an English trading post with the slave trader Dr. Laidley to wait for the rainy season to acclimate and learn Mandingo . At the end of July he fell ill with a fever, which was probably malaria , which was still unknown at the time . Presumably he was partially immunized and thus, without knowing it, emerged stronger from the disease. Today the Mungo Park Memorial stands in Karantaba Tenda and marks the starting point of the journey.

At the end of November 1795, Park broke inland from Pisania. On December 3, he said goodbye to Dr. Laidley, who had accompanied him part of the way:

- “I now had before me unlimited forest and a land whose inhabitants were completely alien to civilized life; and most of which viewed a white man as an object of curiosity or plunder. I considered that I would have parted with the last European I might see and might have abandoned the comforts of Christian society forever. "

Even the most emancipated minds of the time considered European culture to be superior to African culture, and Mungo Park was no exception.

- "How much it is to be hoped that the minds of a people of such attitudes and such fidelity would like to be softened and civilized through the benevolent effects of Christianity!"

Nevertheless, he felt no racist hatred towards the people of Africa, whose culture and customs he considered inferior and not only different, but he was

- "Completely convinced that whatever difference there might be between a Negro and a European in terms of the shape of the nose or the color of the skin, there is none in terms of the real sympathies and characteristic feelings of our common nature."

With him were two servants: Demba, Laidley's house slave, who, if behaved well, was to be given freedom after the journey, and Johnson, who was paid for his services. Johnson spoke Mandingo , while Demba also mastered Serahuli , which enabled both of them to help Park communicate with the people of West Africa.

The group only took one horse, two pack donkeys, and food with them for two days. At first they were accompanied by two slave traders, a Muslim traveler and a blacksmith, who also went eastwards.

They crossed the kingdom of Wuli without any major problems , to whose king Mansa Jatta they had to “give” four sticks of tobacco as customs in Medina. In contrast to the bloody second trip, “giving oneself free” was typical for Park's first expedition. Since white people were not unknown near the coast, Park and his companions were warmly received by the residents of Wuli.

On December 13th they reached the town of Tallika in Bondu . Park noted that Bondu residents are more under the influence of "Mohammedan laws". On December 21, he arrived in Fatteconda, the capital of Bondus. Since there were no hotels or the like in the interior of the country, it was customary for strangers to wait in the center of the village until they were invited by locals to stay overnight, which Park was rarely refused ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 71). However, the authorities in particular often responded with distrust of the peaceful intentions of the purpose of his trip. The ruler Bondus, the Almami Amadi Isati , said:

- "It is impossible, he said, that anyone would undertake such a dangerous journey with their five senses just to look at the country and its people."

According to Park, it was "evident that his suspicions arose from the belief that every white man must necessarily be a merchant."

At that time there was war between Kaarta and Bambara and Mungo Park encountered a number of refugees. In order not to get between the fronts, he chose the north-eastern route via Ludamar to get to Bambara, which in retrospect turned out to be a mistake.

Captive by the Moors

It was not easy to get his servants Demba and Johnson to travel on to Ludamar because:

- “The wild and defiant demeanor of the Moors had deterred my people so much that they declared that they would rather renounce any claim to reward than travel even one step further east. Indeed, the danger they portrayed of being seized by the Moors and sold into slavery became more evident with each passing day; and I couldn't judge their concerns. "

This fear was not unfounded, because according to Park, blacks were inferior from the point of view of the Arab Moors and Tuareg :

- "These hospitable people [the blacks] are viewed by the Moors as a worthless slave brood, and treated accordingly."

Nevertheless, they left Jarra, a town on the border with Ludamar, on February 27, 1796, and arrived at Deena on March 1. The welcome by the Moors was extremely hateful, according to the Park:

- “They hissed, screamed, and cursed me; they even spat in my face, intending to irritate me, so that I would give them an excuse to confiscate my luggage. But when they realized that such insults were not having the desired effect, they resorted to the final and decisive argument that I was a Christian and that what I owned was, of course, legitimate prey for the followers of Muhammad. So they opened my bundles and took everything they liked from me. "

Park was captured on March 7th, not only because of his strangeness, but also because he was believed to be a spy. Probably the Moorish ruler Ali suspected , and not entirely wrongly, that Park's backers want to dispute the Moors for the Trans-Saharan trade :

- “I was a stranger, I was unprotected, and I was a Christian. Each of these circumstances, taken individually, is sufficient to banish any spark of philanthropy from the heart of a Moor. But if they were to be found united in one person, as in my case, if there was still general suspicion that I had come to the country as a spy, every reader will easily imagine that in such a situation I would do anything feared. "

He spent the beginning of his captivity in Ali's camp in Benown. At first he had to share his accommodation with a pig, which is an unclean animal for Muslims. As of May 1796, the camp was relocated to the north of Bubaker due to the war.

Christians were largely unknown in this inland area:

- “It is likely that many of them had never seen a white man before I arrived in Benown. But all had been taught to regard the Christian name with incomprehensible disgust, and to consider it almost as permissible to murder a European as to kill a dog. "

In the end, despite Park's complaints, his servant Demba was enslaved. Johnson, who did not want to travel any further, returned to the Gambia with some of Parks' notes. Park himself was able to escape on the morning of July 2nd at an opportune moment, which also grew out of Ali's falling interest in himself. He had lost everything but his horse and a compass. For the first time he was traveling alone in Africa and completely dependent on the help of locals.

Reaching the Niger

On the way through Bambara, which lies in the Sahel zone, he suffered from great thirst for days. Brought all his gold and gifts, he now had to beg for food. He was given little more than one night's custody in the poor villages of this area, preferring “scattered huts without the walls” , “knowing that in Africa, as in Europe, hospitality is not always to be found in the highest dwellings. "

On July 21, 1796 he reached Niger:

- “As I looked ahead, I saw with infinite joy the great aim of my mission; the long-sought majestic Niger, glittering in the morning sun, as wide as the Thames at Westminster, and slowly flowing in an easterly direction. "

Even though two Portuguese embassies penetrated deep into the interior of West Africa in the 16th century, little is known about their success (Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 36; Duffill, 1999, p. 28). Mungo Park was therefore the first European on the banks of the Niger, from whom this is proven today.

He got as far as Silla downstream, but at the end of July 1796 had to realize that it was better to turn back. On the one hand because the rainy season had started, on the other hand because there was a risk of being captured again:

- “Above all, however, I became aware that I was hurrying more and more into the arms of those ruthless fanatics [of the Moors]; and my inclusion in Sego and Sansanding made me fear that if I did not enjoy the protection of a man of respect among them for which I had no means to procure, and so would I, I would perish myself trying to reach Jenne useless sacrifices fall because my discoveries would have to go under with me. "

Seven months stay in Kamalia

Feverish and exhausted, Park passed through the village of Kamalia in Manding on September 16, 1796, where he was taken in by the Muslim slave trader Karfa Taura . Park received the offer to stay with him until the end of the rainy season and then travel with him to the Gambia, where Karfa wanted to sell a few slaves. Park stayed in Kamilia for seven months. He used the time to gain an insight into the life of the people in Manding, who mostly belonged to the ethnic group known today as the Malinke . He devoted a lot of space to these descriptions in his travelogue. On April 19, 1797, Karfa Taura and Park set out under the protection of a 73-person caravan and arrived on June 10, 1797 at the starting point of Park's journey in Pisania on the Gambia.

Return to Great Britain

Europe's trade with the cities of the Gambia was not very strong at the time. Therefore, Park had difficulties getting direct ship passage to Europe. Finally he cast off on June 17 in Kaiai , referred to by him as Kayee , on board the American Charlestown for the West Indies . After crossing the Atlantic, the sailor headed for the island of Antigua , influenced by unfavorable winds . From there, Park received a passage to England and went ashore in Falmouth on December 22nd . On December 24, 1797, the man believed dead arrived in London.

Park's trip was the first and only complete success for the African Association . He was invited to London society for a few months before returning to Selkirk to write his travelogue Travels in the Interior of Africa . The book appeared in 1799 together with a map by James Rennell , which was called Geographical Notes on Mr. Park's Travels . It was a great success. Six editions were published by 1810, and it was translated into German and French as early as 1800. The report is still a recognized classic in the travelogue literary genre today .

Between trips: Park as a doctor, father and husband

In 1798, Mungo Park received an offer to explore Australia from Banks . After initial interest, Park declined on the official grounds that the financial offer seemed too small for the government to consider the expedition to be a trip of some importance ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 128) . Much more likely, however, according to his brother-in-law James Dickson in a letter to Banks, "that there is a personal connection, a love story in Scotland, but there is no money in it [...] which is the cause." Behind the love story was that then 19-year-old Allison Anderson, the daughter of his old teacher Thomas Anderson, whom Park had already met during his training. The wedding took place in Selkirk on August 2, 1799.

Park would have liked to set off on a second expedition to the Niger in 1800. However, he did not receive an offer from the government. So he settled with his family in Peebles in 1801 with little joy as a doctor . “Being a country doctor is an arduous profession at best; and I will be happy to hang up the lancet and plaster shell if I can get a more suitable position, ” wrote Park to Banks in October 1801. However, there were delays and so his wife Allison was already six months pregnant with the fourth child when Park was finally able to set off on his second trip in 1805.

The second trip: the government expedition

Negotiations with the government

In October 1803, Park received the offer of another expedition to Niger from the British government. However, the government of Prime Minister Henry Addington resigned in May 1804, so it did not come to that for the time being.

Park used the time to improve his Arabic in Peebles. He also wrote a memorandum , a kind of application letter, which was presented to the new British Secretary of War, Lord Camden, on October 4, 1804. The goals of his trip are "the expansion of British trade and the expansion of our geographical knowledge" and he also wants to investigate "whether any part of the country would be useful for colonization for Great Britain" . Park knew these were the government's goals, but in reality paid little attention to such questions during his second trip. He was still concerned with exploring the course of the Niger. Park at the time advocated the theory that the Niger and the Congo were one river. He went on to write in his memorandum: "My hopes of returning to the Congo are, on the whole, not unrealistic" .

On January 2, 1805, he received a formal government mandate to “follow the course of this river to the greatest possible distance that can be discerned; To establish communication and communication with the various peoples on its banks; to receive all indigenous knowledge regarding these peoples, as far as it is in your power ... "

Based on the experiences of the first trip, he decided to travel under the protection of a caravan . This promised not only security against the harsh nature, but also against the arbitrariness of African rulers. The disadvantage was that he would only make slow progress and therefore could not afford to leave too late if he wanted to avoid the rainy season.

The government appointed Park captain and thus head of the state expedition. His brother-in-law Alexander Anderson was second in the ranking as a lieutenant. Also on board was George Scott as a draftsman. The crew also included Lieutenant Martyn, two seamen, a sergeant, a corporal and 33 ordinary soldiers who had been transferred to Gorée for punishment and could be lured with the promise of a pardon after the voyage. There were 45 Europeans in total. In addition, 15 to 20 African craftsmen were supposed to be moved from Gorée to travel with them, but none of them wanted to embark on this adventure. There were also four ship carpenters who were supposed to build two 12-meter boats from the material that was transported all the way to Niger. On the spot they bought about fifty donkeys and six horses. Park now had animals and equipment worth more than 2000 pounds with him, far more than on his first trip, which was financed by the African Association ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 183).

By the time Park set sail aboard the freighter Crescent on January 31, 1805 , he was already three months behind his own schedule. Already at this point it should have been clear that it would be almost impossible to travel to Niger within the dry season . It was not until April 15, 1805 that they went ashore in Kaiai on the Gambia . The crossing had taken longer than expected and put him back on schedule. Instead of staying in the Gambia and bridging the rainy season in a sheltered environment, as on the first trip to Pisania, Park quickly made the final travel preparations in order to be able to leave. He was able to hire a trader named Isaaco who was willing to accompany the caravan with his own small group as far as Niger. This was important because, by that point, Park had still not found an African leader willing to embark on this venture. In return, Isaaco received the value of two slaves, which in West Africa was the equivalent of 40 pounds.

Beginning of the rainy season

In Kaiai, Mungo Park had estimated the trip to the Niger River at six weeks, in fact it was now 3 ½ months. For comparison: the caravan on the way back from the first trip with Turfa took about seven weeks ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 197). This was because the dreaded rainy season began on the night of June 5, 1805 ( Lit .: Sattin, 2003, p. 239). Park "trembled at the thought that we were only halfway through our trip [to Niger]" when they stopped in Shrondo on June 10, 1805.

Turning around would hardly have been better, and so they struggled through muddy paths and overflowing rivers. On August 19, they reached Niger near Bamako . The rainy season had weakened the caravan badly. From the onset of the rainy season to the arrival on Niger, 31 men or two thirds of the group died, most of them from disease ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 192). Weakened in this way, they were more often the target of raids, and the tariff demands of the African rulers increased. When it arrived at Niger, the original caravan had shrunk to ten to twelve people ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 197).

On the boat along the Niger

Due to the rains, the river swelled to a width of one and a half, at rapids up to three kilometers and had a speed of about 8 km / h. After a two-day break, they decided to build a boat in Sansanding, where they arrived on September 26, 1805. Park named the vehicle "HMS Joliba" after the native name of the Nigerian . The Joliba was built because of the numerous rapids so that they only had a draft of about 30 centimeters. The remaining men stayed in Sansanding for a total of two months. Before that they had secured the protection of Mansong , the ruler of Bambara , with the help of a number of gifts . It never occurred to Park to have Mansong issue a letter of protection for the further journey. The experience of later travelers like Friedrich Konrad Hornemann or Jean Louis Burckhardt showed that such a kind of reference letter could be helpful when crossing unknown Islamic areas.

On October 28, Park's brother-in-law and friend Alexander Anderson died after a long illness. Despite great sadness, Park continued to have, as he wrote in his last letter of November 17, 1805 to Lord Camden, "the firm resolve to discover the mouth of the Niger or to perish in the attempt."

Park wrote to his wife that he had no intention of stopping or docking the ship until he reached the coast in late January 1806. The companion Isaaco, who left the group here in Sansanding, took these letters back to the Gambia, together with the travelogue, which was later published as The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa in the year 1805 . It was the last received news from Parks. Nothing was heard from the expedition group until reports of a disaster reached the Gambian settlements.

Finding Mungo Park

By a happy coincidence, Major Charles Maxwell, who was in command on Gorée , learned in early 1810 that Isaaco was on the Senegalese coast. Isaaco was obliged to return to Sansanding in the same year in order to find out the fate of Parks. He returned in September 1811 with a report from Amadi Fatoumas. Amadi was taken into service in Sansanding to replace Isaaco as leader and remained in that capacity until Yauri was reached.

Park must have been very cautious during the river trip. He tried to keep contact with the population to a minimum in order to avoid attacks by residents of Niger. So they probably didn't visit Timbuktu in order not to take any additional risk. They were now in Tuareg territory , and Park must have remembered his captivity from the first trip. Approaching locals were often shot, often out of misunderstandings ( Lit .: Müller, 1980, p. 224). But there were also several attacks by the Tuareg on Park's boat, which were repulsed with rifles. Park and his companions were extremely brutal ago and so Amadi stated for the record, "killed a large number of men." Even years later came other explorers embarrassed because they such as 1826 Gordon Laing for "Christians [were held], the war was waged against the inhabitants of the banks of the Niger and which killed several of the Tuareg and wounded many. ” Even 50 years later, locals told Heinrich Barth about the barbaric behavior of Parks.

After the end of the Tuareg country, however, the onward journey was more peaceful. They also made faster progress due to the northeast trade wind . In the second half of January, according to Amadi, they reached Yauri, where he left the group as agreed. At that time, he said there were four Europeans, but most other sources said two to three. Park now had to realize that the Niger flows into the Atlantic, which could not be far away.

However, in late January or early February 1806, Mungo Park found death on the Niger. Since his diary was never discovered, there are several theories as to the exact cause. According to Amadi, the ruler Yauris withheld the gifts he received from Park from his “king”. The betrayed ruler then attacked Park near Boussa when he got stuck with his boat on a rapids. However, it was also reported that the Africans only approached HMS Joliba to warn Park and his companions of the dangerous rapids. The tour group, now without a guide and interpreter, misunderstood this approach as hostile and opened fire. Another story by Richard Lander suggests that Park was mistaken for the Fulani vanguard . At that time they were conducting a jihad against the Hausa and were also advancing from north to south. On the whole, however, it was primarily the delayed departure of Parks and the associated rainy season that cost him and his companions their lives. In the film Into the hot heart of Africa - A journey of discovery on Niger (2/2) - Beyond Timbuktu , in which Mungo Park's journey through Africa along the Niger is reported, those involved assume that Mungo Park is very profane with its Boat capsized in the rapids and drowned in the process.

Review and Afterlife

It was not until 1830 that the Niger delta was discovered by the brothers Richard and John Lander . However, due to the many rapids, the river turned out to be almost unusable as a transport route inland. The hopes of the British government for colonization and trade relations were not fulfilled. Nevertheless, the building of steamships, the use of quinine against malaria and the advancement of weapons around 1900 led to Timbuktu being conquered by France and Nigeria by Great Britain. The city of Bussa , where Park was once killed, had to give way to the Kainji reservoir , which was completed in 1968, and no longer exists today.

In 1827, Thomas, Park's second son, went ashore on Guinea's coast. His goal was Bussa because he believed rumors that a 50-year-old white man, possibly his father, was being held there. After walking a short distance, he died when he fell from a tree. After a long day's hike, he had quenched his thirst with alcohol. Park's widow died in 1840.

In 1826 the botanist Robert Brown named a genus of "jungle giants" from the legume family Mungo Park in honor of Parkia .

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society has awarded the Mungo Park Medal since 1930 in recognition of excellence in geographical areas and / or a practical contribution to humanity in potentially dangerous environments.

In TC Boyle's novel Water Music , Mungo Park is the main character.

Former British Caledonian Airways named one of their two Boeing 747s after Mungo Park.

literature

Mungo Parks travel reports

- Anonymous: Life and Travels of Mungo Park in Central Africa , London 1838 ( e-book in Project Gutenberg ( currently not available to users from Germany as a rule ) )

- In addition to explanations about the life of Mungo Park, this book contains the full report of his first trip, Travels in the Interior of Africa , supplemented by a summary of Park's second trip and the expeditions of Denham , Clapperton , Laing , Caillié and other travelers to Africa.

- online at archive.org (Edinburgh 1839)

- Mungo Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa - Vol 1 ( e-book in Project Gutenberg ( currently not available to users from Germany ) ) and Travels in the Interior of Africa - Vol 2 ( e-book in Project Gutenberg ( for users currently not available from Germany ) ), Cassell & Company edition by David Price, 1893.

- These two books correspond to the report on the first trip in a slightly abridged version.

- Notes on the history of the edition here .

- Mungo Park: The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa in the Year 1805, with an Account of the Life of Mr. Park (by John Wishaw) , London 1815 ( e-book in Project Gutenberg ( for users from Germany currently usually not available ) )

- This book describes the second trip together with the reports of the guides Isaaco and Amadi Fatoumas.

- Mungo Parks Travel in Africa: From the West Coast to Niger ( digitized in Google book search)

- Travel in the interior of Africa ( digitized in the google book search)

- Mungo Park: Travel to the heart of Africa. On the trail of the secret of Niger . Edition Erdmann, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-86539-819-2 .

Secondary literature

- Kenneth Lupton: Mungo Park the African Traveler , Oxford University Press, Oxford 1979, ISBN 0-19-211749-1 ; Translated into German by Wolfdietrich Müller: Mungo Park. 1771-1806. A life for Africa , FA Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 1980, ISBN 3-7653-0317-8 (an extensive biography)

- Mark Duffill: Mungo Park: West African Explorer from the Scots' Lives series , NMS Publishing Limited, Edinburgh 1999, ISBN 1-901663-15-9 (a compact biography)

- Anthony Sattin: The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu , HarperCollionsPublishers, London 2003, ISBN 0-00-712234-9 (This book is about the African Association and its travelers; Chapters 8,9,10 and 13 via Mungo Park)

- Albert Adu Boahen : Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan, 1788–1861. Oxford 1964 (dissertation by an important African historian on the political background of British Africa research with a detailed description of the role of Mungo Parks)

- TC Boyle : Wassermusik , Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990, ISBN 3-499-12580-3 (novel)

- Rudolf Wenk: Mysterious Electricity , Prisma-Verlag Zenner and Gürchott, Leipzig 1960, new edition under the name of the author Rudi Czerwenka , digital edition, Pinnow 2011, ISBN 978-3-86394-080-5

Original quotations and individual references

- ↑ Anthony Sattin: The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu, HarperCollionsPublishers, London 2003, p. 1

- ↑ Eight small fishes from the coast of Sumatra , the original title of Park's essay (Anthony Sattin: The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu, HarperCollionsPublishers, London 2003, p. 132)

- ↑ "if I succeed I shall acquire a greater name than any (man?) Ever did!" (Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 36)

- ↑ "... the map of its Interior is still but a wide extended blank ..." and "... that ignorance must be considered as a degree of reproach upon the present age." (Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 21)

- ↑ see Anthony Sattin: The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu , HarperCollionsPublishers, London 2003, ISBN 0-00-712234-9 , p. 123

- ↑ “My instructions were very plain and concise. I was directed, on my arrival in Africa, 'to pass on to the river Niger, either by way of Bambouk, or by such other route as should be found most convenient. That I should ascertain the course, and, if possible, the rise and termination of that river. That I should use my utmost exertions to visit the principal towns or cities in its neighborhood, particularly Timbuctoo and Houssa; and that I should be afterwards at liberty to return to Europe, either by the way of the Gambia, or by such other route as, under all the then existing circumstances of my situation and prospects, should appear to me to be most advisable. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “for they were sure he would never return” (Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 19)

- ↑ “If I should perish in my journey, I was willing that my hopes and expectations should perish with me; and if I should succeed in rendering the geography of Africa more familiar to my countrymen, and in opening to their ambition and industry new sources of wealth and new channels of commerce, I knew that I was in the hands of men of honor, who would not fail to bestow that remuneration which my successful services should appear to them to merit. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "a passionate desire to examine into the productions of a country so little known, and to become experimentally acquainted with the modes of life and character of the natives." (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “I had now before me a boundless forest, and a country, the inhabitants of which were strangers to civilized life, and to most of whom a white man was the object of curiosity or plunder. I reflected that I had parted from the last European I might probably behold, and perhaps quitted for ever the comforts of Christian society. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "How greatly is it to be wished, that the minds of a people so determined and faithful, could be softened and civilized by the mild and benevolent spirit of Christianity!" (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "Fully convinced that whatever difference there is between the Negro and European, in the conformation of the nose and the color of the skin, there is none in the genuine sympathies and characteristic feelings of our common nature." (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "it is impossible, he said, that any man in his senses would undertake so dangerous a journey, merely to look at the country and its inhabitants" (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "evident did his suspicion had arisen from a totaled, did every white man must of necessity be a trader" (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “the savage and overbearing deportment of the Moors, had so completely frightened my attendants, that they declared they would rather relinquish every claim to reward, than proceed one step farther to the eastward. Indeed, the danger they incurred of being seized by the Moors, and sold into slavery, became more apparent every day; and I could not condemn their apprehensions. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "These hospitable people are looked upon by the Moors as an abject race of slaves, and are treated accordingly." (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ^ "They hissed, shouted, and abused me; they even spit in my face with a view to irritate me, and afford them a pretext for seizing my baggage. But, finding such insults had not the desired effect, they had recourse to the final and decisive argument, that I was a Christian, and of course that my property was lawful plunder to the followers of Mahomet. They opened my bundles accordingly, and robbed me of every thing they fancied. My attendants, finding that every body could rob me with impunity, insisted on returning to Jarra. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “I was a stranger, I was unprotected, and I was a Christian; each of these circumstances is sufficient to drive every spark of humanity from the heart of a Moor; but when all of them, as in my case, were combined in the same person, and a suspicion prevailed withal, that I had come as a spy into the country, the reader will easily imagine that, in such a situation, I had every thing to fear. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “It is probable that many of them had never beheld a white man before my arrival at Benowm; but they had all been taught to regard the Christian name with inconceivable abhorrence, and to consider it nearly as lawful to murder a European as it would be to kill a dog. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "scattered huts without the walls" preferred: "knowing that in Africa, as well as in Europe, hospitality does not always prefer the highest dwellings." (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "looking forwards, I saw with infinite pleasure the great object of my mission - the long-sought-for majestic Niger, glittering in the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster, and flowing slowly to the eastward." (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “But about all, I perceived that I was advancing more and more within the power of those merciless fanatics; and from my reception both at Sego and Sansanding, I was apprehensive that, in attempting to reach even Jenne, (unless under the protection of some man of consequence amongst them, which I had no means of obtaining,) I should sacrifice my life to no purpose, for my discoveries would perish with me. " (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ "that thier is some private connection, a love affair in Scotland but no money in it ..., that is the cause of it" ( Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 106)

- ↑ “A country surgeon is at best a laborious employment; and I will gladly hang up the lancet and plaister ladle whenever I can obtain a more eligible situation. ” (Park: Travels in the Interior of Africa )

- ↑ “the extension of British Commerce, and the enlargement of our Geographical Knowledge” and “whether any part of it might be useful to Britain for colonization” ( Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 146)

- ↑ “to pursue the course of this river to the utmost possible distance to which it can be traced; to establish communication and intercourse with the different nations on the banks; to obtain all the local knowledge in your power respecting them, ... ” ( Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 150)

- ↑ "trembled to think that we were only half way through our journey [to the Niger]." (Park: The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa in the Year 1805 )

- ↑ “the fixed resolution to discover the termination of the Niger or perish in the attempt” ( Lit .: Lupton, 1979, p. 178)

- ↑ "killed a great number of men." (Park: The Journal of a Mission to the Interior of Africa in the Year 1805 )

- ↑ "the Christian who made war upon the people inhabiting the banks of the Niger, who killed several, and wounded many of the Tuaric." (EW Bovill, Friedrich Hornemann, Alexander Gordon Laing: Missions to the Niger Vol. I: The Journal of Friedrich Hornemann's Travels from Cairo to Murzuk in the Years 1797-8; The Letters of Major Alexander Gordon Laing 1824-6. Page 294) (Unfortunately, this book can hardly be found, therefore quoted from EW Bovill: The Death of Mungo Park , Geographical Journal, Vol. 133, No. 1 (Mar., 1967), p. 6, to which the comments on Barth also refer. )

- ↑ Into the hot heart of Africa - A journey of discovery on the Niger (2/2) - Beyond Timbuktu , film by Werner Zeppenfeld, broadcast on January 20, 2015, 8:15 a.m. on phoenix.

Web links

- Literature by and about Mungo Park in the catalog of the German National Library

- Mungo Park Medal from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

- Wassermusik - newspaper article in the FAZ of October 5, 2003, investigates the circumstances of Mungo Park's death

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Park, mongoose |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British explorer of Africa |

| BIRTH DATE | September 11, 1771 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Foulshiels at Selkirk , Scotland |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 1806 or February 1806 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | near Bussa , Nigeria |