Djedkare

| Name of Djedkare | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Ḏd-ḫˁ.w Constantly on appearances |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Ḏd-ḫˁ.w-nb.tj Constantly on appearances of the two mistresses |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Ḏd-bjk-nbw The Enduring [Goldfalke] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Ḏd-k3-Rˁ Continuous Ka force of Re

Ḏd-k3-Ḥr. (W) Enduring Ka-power of Horus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Jzzj |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turin Royal Papyrus |

Djedu Ḏdw |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.32) |

Ḏd-k3-Rˁ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No.31) |

M3ˁ.t-k3-Rˁ The Maat and Ka-Kraft of Re / (with) Maat and Ka-Kraft, a Re prescription from Ḏd to M3ˁ.t |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Tancheres |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Djedkare ( Djed-ka-Re , also Djedkare Isesi or Djedkare Asosi ) was the eighth king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 5th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled approximately during the period from 2410 to 2380 BC. So far little is known about his person and especially his exact position within the royal family of the 5th dynasty. During his reign there were significant reforms in the state administration. Inscriptions and images bear witness to numerous war and trade expeditions to Syria , Nubia and Punt . In the religious area a change took place under Djedkare, in the course of which the strong veneration of the sun god Re declined. Instead, Osiris, the god of the dead, took on an important role, which is documented for the first time during Djedkar's reign. This religious change also meant that Djedkare no longer built a solar sanctuary , as was common practice for the previous rulers of the 5th dynasty. The king can be assigned a pyramid complex in the south of Saqqara , in which the remains of his mummy were found.

Origin and family

Djedkares exact position within the royal family of the 5th dynasty is not known.

His royal wife was Setibhor . Her name was not known for a long time and was only found in 2019 in her pyramid complex next to the Djedkares. The size and design of her pyramid complex suggest that Setibhor had a social status that went well beyond that of an ordinary royal consort. The exact nature of their position is not yet known. It is possible that Djedkare was only able to assert his claim to the throne by marrying her. Perhaps she also ruled temporarily as regent after Djedkare's death until Unas was able to ascend the throne. Another wife could have been Meresanch IV , whose mastaba (82) is in Saqqara.

Six children of Djedkare are known for their tombs in Sakkara and Abusir . These include the two sons Isesianch and Neserkauhor and the four daughters Chekeretnebti , Hedjetnebu , Mereretisesi and Nebtiemneferes . In addition, Tisethor, a daughter of the Chekeretnebti and thus a granddaughter of Djedkare, is known. From Chekeretnebti, Tisethor and Hedjetnebu the remains of their mummies were found in Abusir, from which it was possible to determine the age of death. All three died at a very young age: Chekeretnebti between the ages of 30 and 35, their daughter Tisethor between the ages of 15 and 16 and their sister Hedjetnebu between the ages of 18 and 19.

The relationship between the king and his successor Unas has not yet been clarified.

Domination

Term of office

The exact duration of Djedkare's reign is unknown. The Royal Papyrus Turin , which originated in the New Kingdom and is an important document on Egyptian chronology , gives 28 years, which began in the 3rd century BC. Living Egyptian priests Manetho 44. The highest contemporary date with certainty is a “21. (or 22nd) times of the census ”, which means the nationwide census of cattle originally introduced as the escort of Horus for the purpose of tax collection. The fact that these counts initially took place every two years (that is, an “xth year of counting” followed by a “year after the xth time of counting”), but later also take place annually, poses a certain problem (an “xth year of counting” was followed by the “yth year of counting”). An alabaster vessel ( Paris , Louvre , Inv.No.E 5323) shows the celebrations for the king's first Sed festival , which ideally was celebrated on the 30th anniversary of the throne.

On the basis of the dates known so far and the determination of the age of death of his mummy, a reign is considered likely in research that is slightly longer than the information in the Turin papyrus and was at least 28 or 29 years, but probably a little more.

State administration

Djedkare carried out far-reaching reforms in the state administration, the aim of which was to bundle as many competencies as possible in one office, namely that of the vizier ( Tjati ). The offices of “ Head of the Two Treasure Houses ”, “Head of the Two Barn” and “Head of the scribes of the royal documents” were held exclusively by viziers and the office of “Head of all the king's work” was closely related to that of scribe - Head linked. The number of middle administrative offices has been greatly reduced. At the same time, the vizier's office was no longer occupied by one, but by two dignitaries, one of whom was responsible for the residence and the other for the provincial administration .

Under Djedkare's reign, Senedjemib Inti was vizier and chief architect. Other viziers were Ptahshepses , Seschemnefer III. , Raschepses and Ptahhotep .

External relations and expeditions

During Djedkare's rule there were several trade expeditions and military campaigns to the northern and southern neighboring areas of Egypt. Several rock inscriptions tell of expeditions to the turquoise mines in Wadi Maghara on the Sinai Peninsula . An inscription from the port of Ain Sukhna , which in Djedkares says “7. Year of the Count ”, suggests that this place was probably the starting point for the Sinai expeditions. An alabaster fragment found in Byblos ( Beirut , American University of Beirut Archaeological Museum , Inv.-No. 5018) with the name of the king shows trade relations with this city. An autobiographical inscription from the grave of an official named Ini from the 6th Dynasty reports on events from Djedkare's reign in the run-up to the description of Ini's own expeditions to the Near East . Nothing is known about their details, however, as only minimal remains of the relevant section of the inscription have survived. A war campaign to the Middle East is evidenced by a picture in the grave of Inti in Deschascha . It shows the capture of a fortress. This scene is also significant because it contains one of the oldest depictions of a scaling ladder . A gold-plated seal of an official from the time of Djedkare ( Boston , Museum of Fine Arts , Inv.-No. 68.115) indicates trade relations with the Aegean .

In 2017, an Old Kingdom administrative complex was excavated in Edfu . The finds made there prove that it was already used under Djedkare as a starting point for expeditions to Wadi Baramiya and possibly to Marsa Alam , which had the goal of exploiting the quarries and mines of the eastern desert .

Expeditions to Nubia, south of Egypt, are evidence of seal impressions from Buhen , a stele in the diorite quarries of Toschqa, and inscriptions on the caravan route between the oases of Dachla and Dungul and in Tômâs . From the 6th dynasty there is also an autobiographical inscription by the expedition leader Harchuf , in which a copied letter from King Pepi II mentions an expedition that took place during the reign of Djedkare. The destination of this expedition was the land of Punt , from where the leader Bawerdjed brought a "dwarf", probably a pygmy , back to the Egyptian court.

Construction activity

The most important building from Djedkare's reign is his pyramid called "Isesi is beautiful" in the south of Saqqara. In addition, several graves of queens and children in Saqqara and Abusir are known. Letters from the king to his vizier and chief architect Senedjemib, which he had copied as inscriptions in his grave in Gizeh , also mention a Hathor chapel (a so-called "Mereret sanctuary") and a jubilee palace for the king's Sedfest, which was run by Senedjemibs Line were established. However, both structures have not yet been archaeologically proven.

The Djedkare pyramid

Djedkare chose the south of Saqqara as the location for his pyramid. The structure had a base length of 78.5 m and an original height of about 52 m. Compared to the pyramids of the 4th and early 5th dynasties, there are some structural innovations here, some of which were used by Djedkare's successors until the end of the 6th dynasty . The core masonry consists of small, irregular pieces of limestone , which were connected with clay mortar to form six steps, each seven meters high, of which only the bottom three still exist today. As with older pyramids, the entrance to the chamber system is on the north side of the building, but no longer in the pyramid wall, but in the courtyard pavement in front of it, directly in the floor of the north chapel . From there, a descending corridor first leads into a vestibule , from which a horizontal corridor continues, which contains a blocking device with three falling stones made of rose granite . At the end of the corridor there is another falling stone device, behind which is the three-part grave area with an antechamber, the actual grave chamber and a three-aisled magazine room. The vestibule and burial chamber have a saddlecloth made of three layers of large limestone blocks. The grave rooms were badly damaged by stone thieves. Nevertheless, the remains of a basalt sarcophagus and parts of the royal mummy were found here.

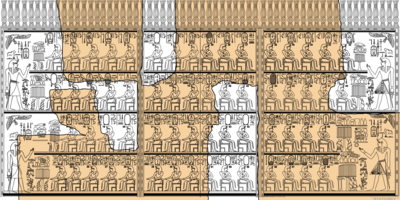

The mortuary temple is on the east side of the pyramid . On its east facade there are two square, tower-like buildings of unknown function, which are perhaps based on similar buildings in the mortuary temple of the Niuserre pyramid . This is followed by an entrance hall, an open courtyard and the inner part of the temple with the holy of holies and numerous storage rooms. There is a small cult pyramid at the southeast corner of the pyramid . The path to the mortuary temple does not run exactly in an east-west direction, but turns slightly to the south. Its lower end and the valley temple have so far only been insufficiently explored.

Family graves in Saqqara

Immediately on the northeast corner of the pyramid is another pyramid complex, which is attributed to a wife Djedkares, who is not known by name. The building has a base length of 41 m and an original height of around 21 m. With a three-tiered limestone core, the structure is very similar to the Djedkare pyramid. The chamber system is largely destroyed. On the east side is the mortuary temple, the entrance to which is in the south-west. From there, a hall with columns and an open courtyard are connected. The latter is separated from the inner part of the temple with the sacrificial hall by a cross corridor. The queen pyramid also has a cult pyramid in its southeast corner.

Also in Saqqara, north of the Djoser pyramid , are the mastaba 85 of the king's son Isesianch and the mastaba 82 of Queen Meresanch IV, whom some consider Djedkare's wife to be.

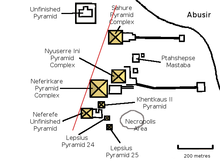

Family graves in Abusir

In Abusir, towards the end of Djedkare's reign, a cemetery of at least six mastabas was built southeast of the pyramid complex of Niuserre, in which several other relatives of the king were buried. The three mastabas of the king's daughter Chekeretnebti and her daughter Tisethor, the king's son Neserkauhor and the official Mernefu form the center of this complex. The three tombs surround a walled courtyard on three sides with facilities for the cult of the dead. The grave of the priest of the dead Faaf (beautiful name Idu) and his wife Chenit are attached to the southwest of the mastaba of Neserkauhor. To the north of the mastaba of Chekeretnebti and Tisethor is the grave of the king's daughter Hedjetnebu. To the north of the Mastaba des Mernefu, but not connected to it, there is another tomb, the owner of which was given the provisional designation "Lady L" by the excavators, as no name has yet been discovered.

Thanks to two inscriptions with dates, the construction time of the cemetery can be determined quite well. The first comes from the grave of the priest Faaf and calls the "year after the 17th count". The first graves of this cemetery built under Djedkare, the mastabas of Chekeretnebti and Hedjetnebu, were probably built only a few years earlier. Neserkauhor's grave dates a little later than that of Faaf. The second inscription comes from the mastaba of "Lady L" and shows it to be the most recent. She calls a "3. Year of Counting ”, but without a royal name. Most likely, the date should refer to the reign of Djedkare's immediate successor Una.

The total construction time of the tombs should cover a period of about 10 to 15 years during the last years of Djedkare's reign and at the beginning of the reign of Unas. Only the grave of the official Mernefu is out of the ordinary here. This is likely to have been erected long before the other graves and was perhaps created under Niuserre.

Also in Abusir is the grave of Djedkare's daughter Nebtiemneferes. The grave of Meretisesi could also have been in Abusir. This is supported by the only known naming of this king's daughter on a relief block in the Brooklyn Museum , which probably comes from the grave of the Chekeretnebti in Abusir.

The mummy of Djedkare

The remains of a male mummy were found inside the Djedkare pyramid during the 1945/46 excavation season. The exact location of the finds was not noted. The mummy remains found include 13 skeletal parts, including parts of the skullcap and facial skull , the lower jaw , the upper half of the spine and parts of the left foot. In addition, several fragments of the bony cortex of the extremities - long bones, as well as fragments of soft tissues with skin and linen bandages - were found. A radiocarbon dating carried out in the early 1990s confirmed that the mummy was classified in the 5th dynasty, which means that it can most likely be assigned to Djedkare. The determined age at death was between 50 and 60 years. Furthermore it was by blood group compared a relationship between the deceased from the Djedkare pyramid and those found in Abusir mummies out of the tombs of Chekeretnebti, Tisethor, Hedjetnebu and "Lady L" to be confirmed.

Statues

The only known round sculptural image of Djedkare is a seated statue made of limestone, which was found around 1900 during excavations under the direction of William Matthew Flinders Petrie in the Osiris temple of Abydos . Only the lower half up to the thighs has been preserved. The lost top was fitted into it by tenons. On the base, on both sides of the feet, there are inscriptions with the throne name Djedkares. The current location of this piece is unknown.

Djedkare in the memory of ancient Egypt

The expeditions that were carried out during Djedkare's reign seem to have been regarded as extraordinary achievements at least until the end of the 6th Dynasty. This is proven by the autobiographical inscriptions by Harchuf and Ini, which refer back to the time of Djedkare in a very similar way. In addition, both people had similar titles, namely that of an expedition leader and that of a Siegler. It can therefore be assumed that at least within a certain class of the civil service there was at times a historical or literary tradition relating to Djedkare's expeditions.

The doctrine of Ptahhotep , a literary work that was handed down at least until the end of the New Kingdom , arose in the Middle Kingdom , probably in the 12th , but perhaps also in the 11th dynasty . The plot of the text is set in Djedkare's time. The fictitious author of the teaching is the high official Ptahhotep, who gives his son and successor advice in the form of 37 maxims for a correct lifestyle.

During the New Kingdom was in the 18th Dynasty under Thutmose III. In the Karnak Temple the so-called King List of Karnak is attached, in which Djedkare's name appears. In contrast to other ancient Egyptian king lists, this is not a complete listing of all rulers, but a shortlist that only names those kings for whom during the reign of Thutmose III. Sacrifices were made.

A relief fragment from the grave of priest Mehu from Saqqara, which dates to the 19th or 20th dynasty , also comes from the New Kingdom . Three deities are depicted on it, facing a number of deceased kings. These are Djoser and Djos erti from the 3rd dynasty and Userkaf from the 5th dynasty. Only a badly damaged signature remains of a fourth king, which was partly read as Djedkare, but occasionally also as Schepseskare . The relief is an expression of the personal piety of the tomb owner, who made the ancient kings pray to the gods for him.

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker : The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 83-85.

- Peter A. Clayton : The Pharaohs. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-8289-0661-3 , p. 62.

- Martin von Falck, Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the early days to the Middle Kingdom. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3737409766 , pp. 145–150.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 113-114.

To names

- Barbara Adams: Ancient Nekhen. Garstang in the City of Hierakonpolis (= Egyptian Studies Association Publication. Volume 3). Clearway Logistics Phase 1b, United Kingdom 1995, ISBN 1-872561-03-9 , p. 126.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 55, 183.

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Freiherr von Bissing : The Re-sanctuary of the king Ne-Woser-Re. Volume I, Druncker, Berlin 1905, p. 158, figure 131.

- Kurt Sethe : Documents of the Old Kingdom. Volume?, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1903-1913, pp. 59-66.

To the pyramid

- Zahi Hawass : The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , p. 257.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Econ, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 153-154.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 180-184.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 361-366.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Djedkare pyramid

Questions of detail

- Ahmed M. Batrawi: The Pyramid Studies. Anatomical Reports . In: Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Volume 47, 1947, pp. 97-111.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 27, 39, 153-155, 188.

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 62-69 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Alfred Grimm: The fragment of a list of foreign animals, plants and cities from the mortuary temple of King Djedkare-Asosi: On three previously unknown African toponyms. In: Studies on ancient Egyptian culture. Volume 12, 1985, ISBN 3-87118-730-5 , pp. 29-41.

- Alfred Grimm: tA-nbw "Goldland" and "Nubia". To the inscriptions on the fragment of the list from the mortuary temple of Djedkare. In: Göttinger Miszellen (GM). Volume 106, 1988, pp. 23-28.

- Peter Jánosi : The pyramid complex of the "anonymous queen" of the Djedkare-Isesi. In: Communication from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 45, 1989, ISBN 3-8053-1106-0 , pp. 187-202.

- Mohamed Megahed: New research in the grave district of Djedkare-Isesi. In: Sokar. No. 22, 2011, pp. 24-35.

- Mohammad Moursi: excavations in the area around the pyramid of Dd-KA-Ra "issj" near Saqqara. In: Annales du Service des Antiquités de l´Égypte. Volume 71, 1987, pp. 185-198.

- Mohamed Moursi: The excavations in the area around the pyramid of Dd-kA-ra "Issj" near Saqqara. In: Göttinger Miscellen. Volume 105, 1988, pp. 65-68.

- Peter Munro : The Unas cemetery northwest. Volume I: Topographical-historical introduction. von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1353-5 , p. 9f.

- Eugen Strouhal, Mohammad F. Gaballah: King Djedkare Isesi and his Daughters. In: W. Viviane Davies, Roxie Walker (Ed.): Biological Anthropology and the Study of Ancient Egypt. British Museum Press, London 1993, ISBN 0-7141-0967-3 , pp. 104-118.

- Miroslav Verner : Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology . In: Archives Orientální. Volume 69, Prague 2001, pp. 363-418 ( PDF; 31 MB ).

- Miroslav Verner: The King Mother Chentkaus von Abusir and some remarks on the history of the 5th dynasty. In: Studies on ancient Egyptian culture. Volume 8, 1980, ISBN 3-87118-497-7 , pp. 243-268.

- Miroslav Verner et al .: Unearthing Ancient Egypt (Objevování starého Egypta) 1958–1988. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague 1990, pp. 32-34.

- Miroslav Verner, Vivienne G. Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. (= Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Volume 6). Charles University, Prague 2002, ISBN 80-86277-22-4 ( online ).

Literary processing

- Ivan Antonovich Jefremow : The journey of Bawardjed. (Prehistory) In: IA Jefremow, Hilde Eschwege: The land from the sea foam (= books for children and young people ). German edition, Verlag für Fremdsprachische Literatur, Moscow 1961.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Alan H. Gardiner: The royal canon of Turin . Panel 2; The presentation of the entry in the Turin papyrus, which differs from the usual syntax for hieroboxes, is based on the fact that open cartridges were used in the hieratic . The alternating time-missing-time presence of certain name elements is due to material damage in the papyrus.

- ↑ Year numbers according to Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1997, p. 369.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 120-121.

- ↑ see M: Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. Prague 2001.

- ^ M. Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. Prague 2001, p. 410; DD Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I, Oakville 2008, p. 84.

- ↑ Petra Andrassy: Investigations into the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom and its institutions (= Internet contributions to Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume XI). Berlin / London 2008 ( PDF; 1.51 MB ), pp. 38–41.

- ↑ Pierre Tallet: Prendre la mer à Ayn Soukhna au temps du roi Isesi. In: Bulletin de la société française d'égyptologie (BSFE). Volume 177/78, 2010, pp. 18-22 ( online ).

- ^ Bertha Porter (†), Rosalind Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings. Volume VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1952, p. 390 ( PDF; 21.6 MB ).

- ↑ Michele Marcolin: Ini. A much-traveled official of the Sixth Dynasty: unpublished reliefs in Japan. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Czech Institute of Egyptology - Faculty of Arts - Charles University in Prague, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-7308-116-4 , p 282-310.

- ↑ William Matthew Flinders Petrie : Deshasheh . The Egypt Exploration Fund, London 1898, panel IV ( PDF; 7.0 MB ).

- ^ Wolfgang Helck : Aegean and Egypt. In: Wolfgang Helck (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie (LÄ). Volume I, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1975, ISBN 3-447-01670-1 , Sp. 69.

- ↑ Press Release Jan. 2018 (submitted Dec. 2017). In: The University of Chicago. Tell Edfu Project. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 114.

- ↑ Edward Brovarski: Giza mastabas. Volume 7: The Senedjemib Complex. Part 1. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 2000, ISBN 0-87846-479-4 ( PDF; 169 MB ), pp. 92-101.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1997, pp. 362-363.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1997, pp. 363-366.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1997, pp. 367-369.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 13-63.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 55-61.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 71-76.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 77-84.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 63-69.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 85-98.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 99-103.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, p. 105.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, p. 108.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, p. 105.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families. P. 68; Brooklyn Museum : Relief of Princess Khekeret-nebty. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ Ahmed M. Batrawi: The Pyramid Studies. Anatomical Reports . In: Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Volume 47, 1947.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, pp. 127, 130.

- ↑ M. Verner, VG Callender: Abusir VI: Djedkare's Family Cemetery. Prague 2002, p. 130.

- ^ William Matthew Flinders Petrie: Abydos I. The Egypt Exploration Fund, London 1902, p. 28, plate LV, 2 ( online ).

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. V. Upper Egypt. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1937, p. 46

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 16 planches]. In: Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. (BIFAO) Volume 85, 1985, p. 270 with XLIV-LIX ( online version ).

- ↑ Michele Marcolin: Ini. A much-traveled official of the Sixth Dynasty: unpublished reliefs in Japan. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Czech Institute of Egyptology - Faculty of Arts - Charles University in Prague, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-7308-116-4 , p 293.

- ^ Günter Burkard , Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume 1: Old and Middle Kingdom (= introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Volume 1). Lit, Münster et al. 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6132-5 , pp. 85-98.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties (= Munich Egyptological Studies. (MÄS) Volume 17). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1969, pp. 60–63.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties. Munich / Berlin 1969, pp. 74-76.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Menkauhor |

Pharaoh of Egypt 5th Dynasty |

Unas |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Djedkare |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Djed-ka-Re; Isesi; Asosi |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king of the 5th dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 25th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 24th century BC Chr. |