Wadi Maghara

| Wadi Maghara in hieroglyphics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old empire |

chetiu mefkat ḫtjw mfk3t turquoise terraces |

|||||||

| Turquoise pebbles , the goal of the expeditions | ||||||||

The Wadi Maghara ( Arabic وادي المغارة, DMG Wādī al-Maġāra 'Valley of the Cave'; ancient Egyptian chetiu mefkat ) is a rock valley on the Sinai Peninsula . It is known for its pharaonic rock reliefs and ancient Egyptian mines .

Research history

The researcher Ulrich Jasper Seetzen wrote the first post-Christian travel reports in 1809. Karl Richard Lepsius led an important research expedition from 1842–1845, during which he documented several rock reliefs in drawings. A second expedition took place in 1868 by the British Ordnance Survey under the leadership of Captains CW Wilson and HS Palmer. Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie made 1904–1905 first excavations at the ancient mines and investigations of the rock inscriptions.

In 1932 the English Harvard University carried out an expedition to Wadi Maghara, during which Nabataean rock reliefs were discovered in the neighboring Wadi Qena . Other expeditions took place from 1967 to 1987, including those under the researcher Raphael Giveon , who rediscovered the relief of the king ( pharaoh ) Djosertali .

topography

The Wadi Maghara is located on the southern Sinai about 19 km as the crow flies east of the village of Ras Abu Rudeis on the Gulf of Suez and runs through a sandstone mountain range as a gorge . It is rich in natural occurrences of copper ore and turquoise .

On the east side of the steep slopes there are the remains of simple dwellings of former quarry workers, on the west side, however, are the entrances to the old mine tunnels. The rock carvings and steles of the kings can also be seen there. Many of them have been destroyed over the years. Those who could be saved were taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo .

The only rock painting that can still be found in Wadi Maghara is that of King Djosertesi from the 3rd dynasty , which was earlier incorrectly attributed to Semerchet ( 1st dynasty ).

Historical significance in ancient Egypt

|

|

|

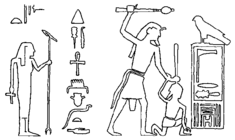

| Rock relief of Sanacht from Wadi Maghara | Djoser rock relief | Sandstone relief of Sneferu |

The Wadi Maghara must have been known to the ancient Egyptians very early. A rock inscription from the reign of King Semerchet ( 1st Dynasty ) documents an expedition into or through the wadi for exchange and trade purposes.

Rock reliefs with the names and images of kings can be found throughout the wadi and come from the Old Kingdom , the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom . All the rulers of these epochs sent numerous expeditions to Wadi Maghara in order to have the deposits of copper , turquoise and malachite exploited there.

Well-known examples include the kings Sanacht and Snefru , who also carried out a military coup against the Iuntiu , who lived in Wadi Maghara , in order to recapture the areas that could only be used temporarily by the Egyptians. Asosi ( 6th dynasty ) sent two expeditions to Wadi Maghara every ten years. From Amenemhet III. there are ten inscriptions about local expeditions.

literature

- Toby AH Wilkinson : Early Dynastic Egypt . Routledge, London / New York 1999, ISBN 0-415-26011-6 .

- Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt . Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 .

- Nicolas Grimal : A History of Ancient Egypt . Wiley & Blackwell, Weinheim 1994, ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8 .

- Mursi Saad El Din, Ayman Taher, Luciano Romano: Sinai: the site & the history . New York University Press, New York 1998, ISBN 978-0-8147-2203-9 .

- Rainer Hannig : Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800 - 950 BC) . von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800 - 950 BC). Mainz 2006, p. 1178.

- ^ Karl Richard Lepsius : Letters from Egypt, Ethiopia and the Sinai peninsula. Wilhelm Hertz (Bessersche Buchhandlung), Berlin 1852, p. 329ff.

- ↑ Great Britain. Ordnance Survey, Sir Charles William Wilson, H. Spencer Palmer: Ordnance survey of Mount Serbál by Captains CW Wilson and HS Palmer under the direction of Major General Sir Henry James… Director General of the Ordnance Survey, 1868-9; pub. by authority of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty's Treasury . Zincographed at the Ordance Survey Office, Southampton 1870, reprinted 1892.

- ^ A b c Kathryn Bard, Steven Blake Shubert: Encyclopedia of the archeology of the ancient Egypt . London 1999, pp. 875-876.

- ^ Mursi Saad El Din, Ayman Taher, Luciano Romano: Sinai: the site & the history . New York 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Alan Henderson Gardiner , Thomas Eric Peet, Jaroslav Černý : The Inscriptions of Sinai Volume 1: Introduction and plates (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Volume 45, ISSN 0307-5109 ). 2nd edition, revised and augmented by Jaroslav Černý, Egypt Exploration Society, London 1955, p. 54, no. 1, plate 1.

- ↑ Abeer El-Shahawy, Farid S. Atiya: The Egyptian Museum in Cairo: a walkthrough the alleys of ancient Egypt . American University in Cairo, Cairo 2005, ISBN 978-977-17-2183-3 , p. 45, image 21.

- ^ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London / New York 1999, pp. 79-81.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. Weinheim 1994, p. 64.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. Weinheim 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. Weinheim 1994, p. 79.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. Weinheim 1994, p. 170.

Coordinates: 28 ° 54 ′ 0 ″ N , 33 ° 22 ′ 0 ″ E