Neferirkare

| Neferirkare | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

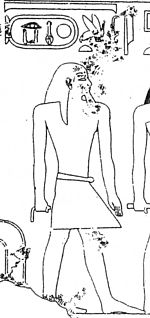

Relief fragment from the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid with a later reworked representation of King Neferirkare

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Wsr-ḫˁ.w With powerful appearances |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Ḫˁj-m-nb.tj He appears as the two mistresses

Wsr-ḫˁw-nb.tj With the powerful apparitions of the two mistresses |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Sḫm.w-nb.w Goldenest of Powers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Nfr-jr (.w) -k3-Rˁ With a beautiful figure and Ka des Re

Nfr-jr (.w) -k3-Rˁ With a beautiful figure and Ka des Re |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

(Ka ka i) K3 k3 j Ruler (with) Ka powers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.28) |

K3 k3 j |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No.27) |

Nfr-jr (.w) -k3-Rˁ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek after Manetho |

Nephercheres |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neferirkare (Nefer-ir-ka-Re) was the third king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 5th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled approximately during the period from 2475 to 2465 BC. There is very little evidence of his person or of specific events during his reign. Neferirkare is known for its construction activity, the central projects of which included a previously undiscovered solar sanctuary and a pyramid complex . During his reign, the 5th Dynasty Annal Stone was probably created , one of the most important documents for Egyptian chronology .

Origin and family

The relationships between the transition from the 4th to the 5th dynasty and in particular the position of the first three kings of the 5th dynasty ( Userkaf , Sahure and Neferirkare) were very controversial for a long time. Attempts at reconstruction were mostly based on the information in the Westcar papyrus from the Middle Kingdom , in which Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare are referred to as brothers. Finds of relief fragments from the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid by Ludwig Borchardt initially seemed to confirm this information. Representations of Neferirkare were subsequently added to several of these fragments, which led Kurt Sethe to suspect that Neferirkare wanted to express a legitimation claim to the throne that he had usurped as the brother of his predecessor and withheld from Sahure's Crown Prince Netjerirenre .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Relief fragments from the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid with subsequently reworked depictions of the Neferirkare |

||

A relief block rediscovered in 2002 made it necessary to reinterpret the previously known evidence. While on the previously known relief fragments Netjerirenre is always referred to as the "eldest son of the king" and Neferirkare's depiction was subsequently added to the head of a priestly procession, the newly discovered block features two eldest royal sons (Ranefer and Netjerirenre), while the priestly depictions have remained unchanged. Tarek El Alwady interprets this representation in such a way that Ranefer is actually the later King Neferirkare. The apparent absence of Ranefer from the fragments described by Borchardt is due to the fact that they always show religious scenes. In which the heir to the throne Ranefer was shown not in his function as prince, but as a priest. After his accession to the throne, he had these representations changed and royal insignia and his throne name added. The newly discovered block, on the other hand, shows a memory scene of a specific historical event (Sahure's punt expedition). There Ranefer is therefore not shown as a priest, but as a prince. The prince's kneeling posture probably made a later revision impossible.

The question of why both Ranefer and Netjerirenre are referred to as the eldest sons of the king can, according to El Awady, be answered with the fact that both were twins . This is expressed by the fact that both were depicted together with Sahure's wife and that Netjerirenre, as the second-born twin, held the office of priest of the fertility god Min , which, according to El Alwady, served as a symbol of Sahure's extraordinary fertility.

Other brothers Neferikares were Chakare , Raemsaf and Heriemsaf . As the mother of Neferirkare and all of his brothers, Sahure's only known wife and biological sister Meretnebty can be regarded.

Neferirkares Great Royal Wife was Chentkaus II. Two sons are known from this marriage: Ranefer, who as the eldest son of the king bore his father's maiden name and later ascended the throne under the name Raneferef , and Niuserre , who also became king after the early death of his brother prevailed.

Domination

Term of office

The exact length of government of the Neferirkare cannot be precisely determined due to the sparse sources. In the 3rd century BC Manetho , living Egyptian priests, names 20 years of reign, which in view of the unfinished pyramid complex Neferirkares, however, is likely to be too high. The royal papyrus Turin from the 19th dynasty is so badly damaged at the point where the entry to Neferirkare was originally that both the royal name and the length of the reign ascribed to it have been lost. On contemporary dates, only three times a “5. Times of the count ”(this should also include a construction worker inscription from the Neferirkare pyramid, which was probably wrongly read as“ 16th time of the count ”.), Which means the nationwide census of cattle originally introduced as the escort of Horus for the purpose of tax collection . The fact that these counts initially took place every two years (that is, an “xth year of counting” was followed by a “year after the xth time of counting”) poses a certain problem with dates from the Old Kingdom could sometimes also take place annually (an “xth year of counting” was followed by the “yth year of counting”). On this basis, a much shorter term of ten or eleven years is assumed today. Miroslav Verner thinks it is also possible that an indication of seven years in the royal papyrus Turin, which is usually attributed to Sheepseskare, is actually assigned to Neferirkare, which would result in an even shorter reign of only six or seven years.

Events

The records of the 5th Dynasty Annal Stone end with Neferirkare's reign , so it appears to have been commissioned under his rule. However, comparatively little information about Neferirkare's rule can be found in this document. The entry shows that he ascended the throne on the 29th Schemu II (29th day in the 2nd month of the heat season). Otherwise, the information is limited to religious acts, such as donations to his solar sanctuary and the issuing of a decree for the temple of Chontamenti in Abydos .

In terms of foreign policy, contacts to Nubia and the Levant seem to have existed under Neferirkare . The seal and ostraka from the Buhen fortress on the second cataract of the Nile are known by his name. In Byblos in what is now Lebanon , an alabaster bowl with the name Neferirkares was found.

administration

Several high officials of Neferirkare are known for their extensive grave structures and the biographical inscriptions placed therein. These inscriptions give a good idea of the power that the king had in the Old Kingdom, but also of the important role his officials played for him. The high priest of Ptah of Memphis , Ptahshepses , saw it as a great honor to be allowed to kiss the king's feet instead of just the ground. Another inscription tells of a ceremony in which the official Rawer is accidentally touched by a staff of the king. According to Egyptian belief, this should actually have resulted in his death, but nothing happens to Rawer, as Neferirkare immediately shouts "Heil" to him. The most important official of Neferirkares was Waschptah , who held the highest office of the vizier and was also chief judge and chief architect. An inscription in his tomb shows that he suffered a fatal attack during a building inspection by the king, whereupon Neferirkare first made personal efforts to recover and, after this was unsuccessful, arranged for Waschptah's funeral. Ti, who later died under Niuserre, was the king's hairdresser. He was in front of the two pyramids of Neferirkare and Raneferef and the four sun sanctuaries of Sahure, Neferirkare, Raneferef and Niuserre. He also oversaw over 100 business domains.

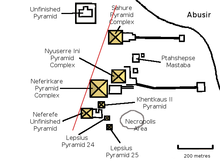

Construction activity

Two construction projects are known from Neferirkare's reign: his pyramid complex, which he had built south of that of his father Sahure in Abusir, and a previously undiscovered solar sanctuary . Some researchers such as Herbert Ricke attributed the expansion and reconstruction of the Userkaf solar sanctuary to him. According to recent considerations by Miroslav Verner, however, it seems more plausible that Neferirkare's predecessor, Sahure, was responsible for this construction work. In addition, Rainer Stadelmann, for example, also suggested that the three solar sanctuaries of Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare are actually one and the same building.

The Neferirkare pyramid in Abusir

Like his father Sahure, Neferirkare also decided on Abusir as a burial place and built his pyramid complex there called "The Ba des Neferirkare". It is made of limestone and has a base area of 105 m × 105 m and an original height of 72 m, making it the largest pyramid in the Abusir necropolis. The structure was erected in two phases: First, an unusual step pyramid was planned - a pyramid shape that had not been used for royal tombs since the end of the 3rd Dynasty . In a second construction phase, however, the system was designed as a real pyramid. First of all, a larger, eight-tier building was placed around the stepped structure, which was only intended as a pyramid core. A panel was finally placed around it, but it remained unfinished. Archaeologically only the lowest layer of rose granite could be proven. How far the cladding that was started originally extended can no longer be reconstructed due to the massive stone robbery on the pyramid.

From the north a corridor leads to the underground tombs. This corridor has a ceiling construction that is unique in the Egyptian pyramid structure: In addition to the flat ceiling, it also has a gable ceiling above , which was separated from the core masonry by a layer of reeds. The antechamber and the burial chamber are oriented east-west. Both rooms are badly damaged by stone robbery. Nothing has been preserved from the original grave equipment.

The temple complex belonging to the pyramid can also be subdivided into several construction phases and was probably only started under Neferirkare's successor Raneferef. Initially, only a small limestone mortuary temple was built. In brick construction, storage rooms were added in the south, a columned hall in the north and an open courtyard and a vestibule in the east. In addition, the pyramid was surrounded with a wall. The roof of the temple was not supported by stone pillars, as is usually the case, but by stucco-covered wooden pillars. The valley temple and the pathway were probably never completed and later usurped by Niuserre for his own pyramid complex.

South of the king's pyramid, Neferirkare had another pyramid built for his wife Chentkaus II. After Neferirkare's death, work on this structure was initially interrupted and then presumably resumed under Raneferef. The pyramid consists of a three-tier, clad core and has a base dimension of 25 m and an original height of 17 m. Remnants of the burial were found inside, including mummy bandages. A mortuary temple on the east side of the pyramid, also built in several phases, was not built until after Neferirkare's death.

The solar sanctuary of Neferirkare

Although the sun sanctuary of Neferirkare with the name “Favorite Place of Re” is the most frequently documented of the six known sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty, it has not yet been archaeologically proven. If it is not identical to the Userkaf sanctuary, it is quite possible that it was only built as a brick structure and that it was no longer converted into stone due to the death of the client, which meant that the building was quickly decaying. Thanks to the written mention, the appearance of the sanctuary can be partially reconstructed: it had a central obelisk, an altar, warehouses, a Sedfest hall and a barque room. The texts also mention that goods were transported by water between the Sun Sanctuary and the mortuary temple of the Neferirkare pyramid. The solar sanctuary does not seem to have been in the immediate vicinity of the pyramid complex.

Neferirkare in the memory of ancient Egypt

In the Middle Kingdom, Sahure was mentioned in a literary work, namely in one of the stories in the Westcar papyrus . The majority of the stories assume the 12th dynasty as the time of origin, although there are now increasing arguments to date them to the 17th dynasty , from which the traditional papyrus also comes.

The action takes place at the royal court and revolves around Pharaoh Cheops from the 4th dynasty as the main character. In order to pass the boredom, he lets his sons tell wonderful stories. After three of his sons have already told him about past miracles, the fourth Hordjedef has a still-living magician named Djedi brought in, who first performs magic tricks. Cheops then wanted to know from Djedi whether he knew the number of ipwt (exact meaning of the word unclear, translated as locks, chambers, boxes) of the Thoth sanctuary of Heliopolis . Djedi denies and explains that Rudj-Djedet, the wife of a Re- priest, will give birth to three sons who will ascend the royal throne. Have the oldest of them find out the number and convey it to Cheops. Djedi adds soothingly that these three will only ascend to the throne after Cheops' son and grandson have ruled. Cheops then decides to go to the home of the Rudj-Djedet. Then suddenly the description of the birth of the three kings follows. The four goddesses Isis , Nephthys , Meschenet and Heket , as well as the god Khnum appear and are led by Rauser, Rudj-Djedets husband, to the woman giving birth. Through dance and magic they help the three kings into the world. Their names are shown here as User-Re-ef, Sah-Re and Keku, so these are the first three kings of the 5th dynasty: Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai.

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume 1: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville CT 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 258-260.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. The timing of Egyptian history from prehistoric times to 332 BC BC (= Munich Egyptological Studies 46). von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 26, 39, 153–155, 159, 161, 175, 188.

- Peter A. Clayton: The Pharaohs. Rulers and Dynasties in Ancient Egypt. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, ISBN 3-430-11867-0 , p. 62.

- Martin von Falck, Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the early days to the Middle Kingdom. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3737409766 , pp. 134-138.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 173-174.

About the name

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Handbook of Egyptian King Names (= Munich Egyptological Studies 20). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich et al. 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 54, 181, 182.

- Paule Posener-Kriéger, Jean-Louis de Cenival (ed.): The Abu Sir Papyri (= Hieratic papyri in the British Museum. Ser. 5). Edited together with complementary texts in other collections. British Museum Press, London 1968, fig. 28.

To the pyramid

- Ludwig Borchardt : The grave monument of King Nefer-ír-ka-re (= Scientific publication of the German Orient Society. Vol. 11 = Excavations of the German Orient Society in Abusir. Vol. 5). Hinrichs, Leipzig 1909 (reprint. Zeller, Osnabrück 1984, ISBN 3-535-00574-4 ), (the excavation publication).

- Zahi Hawass (Ed.): The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , pp. 246-247.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Approved special edition. Orbis, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-572-01261-9 , pp. 144-145.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition. von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , p. 155f. 171-174.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 324–331.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Neferirkare pyramid

To the sun sanctuary

- Miroslav Verner: The Sun Sanctuaries of the 5th Dynasty. In: Sokar. No. 10, 2005, ISSN 1438-7956 , pp. 43-44.

- Susanne Voss: Investigations into the sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty. Significance and function of a singular temple type in the Old Kingdom. Hamburg 2004, pp. 139–152 (Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 2000), ( PDF; 2.5 MB ).

Questions of detail

- James P. Allen: Re'-Wer's Accident. In: Alan B. Lloyd (Ed.): Studies in Pharaonic Religion and Society in Honor of J. Gwyn Griffiths (= The Egypt Exploration Society. Occasional Publications 8). Egypt Exploration Society, London 1992, ISBN 0-85698-120-6 , pp. 14-20.

- Tarek El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. New evidence. In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (Eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Czech Institute of Egyptology - Faculty of Arts - Charles University in Prague, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-7308-116-4 , p 191-218.

- Ludwig Borchardt: The grave monument of King S'aḥu-Re. 2 (in 3) volumes. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1910–1913, ( online version ).

- Volume 1: The building (= Scientific publications of the German Orient Society. Vol. 14, ISSN 0342-4464 = Excavations of the German Orient Society in Abusir. Vol. 6);

- Volume 2: The wall pictures (= Scientific publications of the German Orient Society. Vol. 26 = Excavations of the German Orient Society in Abusir. Vol. 7). 2 volumes (text, picture sheets).

- James Henry Breasted : Ancient Records of Egypt. Historical documents (= Ancient Records. Series 2). Volume 1: The First to the Seventeenth Dynasties. The University of Chicago Press et al., Chicago IL et al. 1906, pp. 111-113, 118 ( PDF; 11.9 MB ).

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 62-69 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. In: Archives Orientální. Vol. 69, 2001, ISSN 0044-8699 , pp. 363-418, ( PDF; 31 MB ).

- Miroslav Verner: The King Mother Chentkaus von Abusir and some remarks on the history of the 5th dynasty. In: Studies on ancient Egyptian culture. Vol. 8, 1980, ISSN 0340-2215 , pp. 243-268.

- Miroslav Verner: Objevování starého Egypta. 1958-1988. (Praće Československého egytologického ústavu Univerzity Karlovy v Egyptě). = Unearthing Ancient Egypt. 1958-1988. (Activities of the Czechoslovak Institute of Egyptology in Egypt). Univerzity Karlovy, Prague 1990, p. 4f.

- Miroslav Verner: Remarks on the Pyramid of Neferirkare. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) 47, 1991, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 411-418 and plates 61-63.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Year numbers according to: Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen.

- ↑ Borchardt: The grave monument of the king Sahure. Vol. 1, p. 13.

- ↑ El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. P. 210.

- ↑ El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. Pp. 213-214.

- ↑ El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. Pp. 214-216.

- ↑ El Awady: The royal family of Sahure. Pp. 198-203.

- ^ Dodson , Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Pp. 62-69.

- ↑ see: Verner: Archaeological Remarks.

- ↑ Verner: The pyramids. P. 300.

- ^ Baker: Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. P. 259.

- ^ Verner: Archaeological Remarks. P. 395.

- ↑ a b c Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. P. 173.

- ^ Baker: Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. P. 260.

- ↑ Breasted: Ancient Records of Egypt. P. 118.

- ↑ Breasted: Ancient Records of Egypt. Pp. 111-113.

- ^ Herbert Ricke, Elmar Edel: The sun sanctuary of King Userkaf. Volume 1: The building (= contributions to Egyptian building research and antiquity. Vol. 7, ZDB -ID 503160-6 ). Swiss Institute for Egyptian Building Research and Archeology, Cairo 1965, pp. 15–18.

- ↑ Verner: The Sun Shrines of the 5th Dynasty. P. 41.

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: Userkaf in Sakkara and Abusir. Investigations into the succession to the throne in the 4th and early 5th dynasties In: Miroslav Bárta, Jaromír Krejčí (ed.): Abusir and Saqqara in the year 2000 (= Archív orientální. Supplementa 9). Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic - Oriental Institute, Prague 2000, ISBN 80-85425-39-4 , pp. 541-542.

- ↑ Verner: The pyramids. P. 331.

- ↑ Verner: The pyramids. Pp. 332-335.

- ↑ Verner: The Sun Shrines of the 5th Dynasty. P. 44.

- ^ Günter Burkard , Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history. Volume 1: Old and Middle Kingdom (= introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Volume 1). Lit, Münster et al. 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6132-5 , p. 178.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Sahure |

Pharaoh of Egypt 5th Dynasty |

Raneferef |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Neferirkare |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Nefer-ir-ka-re; User chau; Kakai; Nephercheres; User-em-Nebti |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king of the 5th dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 2483 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 2463 BC Chr. |