Raneferef

| Name of Raneferef | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Top of a statue of Raneferef; Egyptian Museum , Cairo

|

||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Hˁw-nfr With perfect appearances |

|||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Nfr-m-nb.tj Perfectly in the shape of the two mistresses |

|||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Nfr-bjk-nb.w Perfect golden hawk |

|||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Rˁ-nfr = f He is perfect, a Re |

|||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Jsj Isi |

|||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No.29) |

Rˁ-nfr = f He is perfect, a Re |

|||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Saqqara (No. 29) |

Chai-nefer-Re Hˁj-nfr-Rˁ He appears perfect, a Re |

|||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Cheres |

|||||||||||||||

Raneferef ( Re-nefer-ef , according to another reading Nefer-ef-Re or Nefer-ef-Ra ) was the fourth or fifth king ( pharaoh ) in the 5th Dynasty of the ancient Egyptian Empire . He ascended the Egyptian throne around the age of 20 around 2460, but died around 2455 BC. He is best known for his construction work, the most important projects of which include a previously undiscovered solar sanctuary and a pyramid complex that has already been started . Significant finds concerning him are numerous statue fragments from the mortuary temple of his pyramid and the remains of his mummy from the burial chamber.

Origin and family

Raneferef was born as the son of his predecessor Neferirkare and his wife Queen Chentkaus II . His successor, Niuserre, was his brother. Raneferef's wives and children are not known. But the Queen Chentkaus III, discovered in 2015 . have been his wife. A limestone relief from Abusir proves that Raneferef, as crown prince, still bore the name Ranefer and probably changed it in the course of the accession to the throne. The relationship to Schepseskare , who briefly ruled between Raneferef and Niuserre, is completely unclear . Silke Roth does not rule out the theoretical possibility that it could be a son of Raneferef. Miroslav Verner, on the other hand, thinks it is more likely that he was a son of Sahure and thus an uncle of Raneferef.

Domination

Term of office

The reign of Raneferef should have been only a few years. However, the Egyptian sources give very different numbers. The royal papyrus Turin from the 19th dynasty is so badly damaged at the relevant point that several royal names of the 5th dynasty are missing and basically two entries are possible that can be assigned to either him or his predecessor or successor Schepseskare. The papyrus assigns Raneferef either one year or seven years of government. In the 3rd century BC Manetho , living Egyptian priests, names 20 years, which is probably too high. The highest contemporary documented date is a "first count," which corresponds to the first or second year of the reign. The unfinished state of his pyramid complex and the examination of his mummy, which showed a death age of 20-23 years, speak for an extremely short reign of probably two or three years.

Circumstances of assumption of power and succession

According to the list of kings of Sakkara from the 19th dynasty , Raneferef's father Neferirkare was first followed by a king named Schepseskare , about whom little is known, and only then Raneferef, who in turn was succeeded by his brother Niuserre. However, there are now several reasons why Raneferef directly succeeded his father Neferirkare. On the one hand, the three pyramids of Sahure , Neferirkare and Raneferef were built in close proximity to one another and aligned with one another. This speaks in favor of a direct succession of these three kings. On the other hand, seal impressions with the name of Schepseskare were found in the mortuary temple of the Raneferef pyramid, which indicates the construction activities of this ruler. So he should be seen as the successor and not the predecessor of Raneferef.

In connection with the results of the mummy investigation, according to the current state of knowledge, it can be assumed that Raneferef ascended the throne after the death of his father at the age of about 20. After a reign of two to three years, from which no further events apart from his construction activities have been recorded, he apparently died childless. He was followed by Schepseskare and then Niuserre to the throne. It is still unclear why Niuserre did not succeed his brother Raneferef directly.

Construction activity

Only two of his own construction projects are known from Raneferef's short reign: On the one hand, his pyramid complex in Abusir called "Divine is the power of Raneferef" and a solar sanctuary called "Sacrificial Table of Re ". The latter has not yet been discovered. In addition, he was responsible for completing his father's pyramid complex and presumably also for continuing the construction work on his mother's tomb.

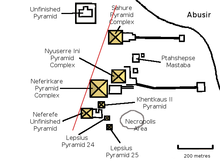

The Raneferef pyramid in Abusir

Like his grandfather Sahure and his father Neferirkare, Raneferef also chose Abusir as the location for his pyramid. It was erected southwest of his father's tomb and stands in a straight line with it and the Sahure pyramid , which was probably aligned with the obelisk of the solar sanctuary of Heliopolis. With a side length of around 65 m, the Raneferef pyramid is significantly smaller than its two predecessors. The foundation was not natural rock, but two layers of large limestone blocks . The outer shell and the walls of the working pit for the descending corridor and the chamber system were clad with roughly hewn limestone blocks that were held together by clay mortar. The pyramid core was filled with sand, gravel and clay. The entrance to the descending corridor is on the north side. This was paved in the lower area with rose granite and had a system of blocking stones of the same material. Approximately in the center of the pyramid the passage leads into the antechamber, which is connected to the burial chamber on its west side by another short passage . Both chambers had a gable ceiling and were clad with limestone.

Due to Raneferef's early death, the building remained unfinished and was only poorly completed under his successors Schespseskare and Niuserre. The truncated pyramid, which had only grown to a height of about 7 m, was clad with limestone. The roof terrace was covered with a layer of clay containing flint rubble. As a result of this reconstruction, the tomb, originally planned as a pyramid, ultimately took on the appearance of a square mastaba . A mortuary temple was erected in two phases on the east side of the building . The first, very small temple was built from limestone and was probably built under Schepseskare. Niuserre later expanded the temple considerably in brick construction and surrounded the pyramid complex with a brick wall.

The sun sanctuary of Raneferef

The sun sanctuary of Raneferef has so far only been handed down through a few written references. There are no known priests of this sanctuary. It is therefore likely that the building was never completed and that the cult was quickly discontinued. It is possible that the unfinished structure was completely demolished and the sun sanctuary of Niuserre was later built at the same place .

The Neferirkare pyramid and the Chentkaus II pyramid

→ Main articles: Neferirkare pyramid and Chentkaus II pyramid

The pyramid of Neferirkare was largely completed when its owner died, but the cladding was still incomplete. Only a bottom layer of rose granite has survived. Hardly any statements can be made about the limestone cladding above due to massive stone theft. Raneferef may have planned to complete it, but that did not happen during his reign or later. The first building phase of the mortuary temple of the Neferirkare pyramid may also go back to Raneferef. This limestone building was only small in size, but had all the space necessary for practicing cult. Under Niuserre, the brick building was greatly expanded.

On the Chentkaus II pyramid located south of the Neferirkare pyramid, construction work was initially suspended between the tenth and eleventh year of Neferirkare's reign. After the death of this ruler the responsibility for the continuation of the construction fell to Raneferef. The extent to which construction continued, however, is unknown, and given his brief reign and other construction projects, it is unlikely that the building will undergo significant expansion. The completion also took place under Niuserre.

The mummy of Raneferef

During the 1997/98 excavation season, the remains of a mummy were discovered in the burial chamber of the Raneferef pyramid, which is very likely that of the king. The findings include a fragment of the occiput , the entire left collarbone , part of the left shoulder blade , the nearly entire left hand, the right fibula and a piece of skin with subcutaneous tissue . In addition, residues were of linen - bandages and two fragments of painted cardboard found. Remnants of the four canopic vessels for the entrails of the deceased were also discovered, but their contents were not preserved. Bones of a right big toe and another skin fragment from a left foot, which were found in the antechamber, could not be assigned to Raneferef, but came from a medieval reburial .

The examination of the royal mummy remains revealed that the corpse was probably dried with baking soda and then coated with a thin layer of resin before it was then given a white, probably calcareous paint coating. Indications of a removal of the brain , as it later became common during the mummification process, could not be found. Through radiocarbon dating of a skin fragment the mummy fragments could be associated with the Old Kingdom clearly. It is therefore extremely likely that it is the remains of Raneferef and not a later reburial.

X-ray examinations of the preserved bones showed that almost all the epiphyseal plates had already closed. The epiphyseal plates on the fibula and collarbone were particularly relevant for determining the age at death. The former was completely closed, which usually happens in the 19th or 20th year of life. The joint on the collarbone, on the other hand, had only just started to close, which usually happens between the ages of 18 and 25. The age at death Raneferef could be limited to 20-23 years.

Statues

In the mortuary temple of Raneferef's pyramid complex, fragments of at least 13 statuettes of the king were found in the 1980s, which are now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. It is best documented by all the kings of the 5th dynasty by round sculptural evidence.

One of the best preserved specimens is a statuette made of pink limestone (Cairo, inv.no. JE 98171), which consists of three fragments: the first includes the entire upper body up to the hips, the second part of the apron and legs and the third the statue base with one foot. The first fragment measures 17.2 cm × 11.2 cm, the second 11.6 cm × 8.1 cm × 3.6 cm and the third 3.2 cm × 7.8 cm × 6.7 cm. The king is shown sitting and holding an elongated object, presumably a club, in front of his chest with his right hand. The left arm is broken off, as is an originally attached beard. The king wears a short-haired wig on his head. A uraeus snake originally attached to the forehead has not survived. Much like some statues of Khafre from the 4th Dynasty king sits here Horus - falcon in the neck and spreads its wings protectively around him.

Another piece of yellowish limestone (Cairo, without inv. No., Excavation no. 993 / I / 84) is made very similarly. Of this statuette, however, only the head has survived. This measures 9.4 cm × 6.7 cm × 8.3 cm. Here, too, the king wears a short-haired wig. The beard and uraeus were made as separate pieces and have not survived. The remains of a Horus falcon with spread wings can be seen on the neck.

A statue made of gray-black slate , which has been preserved from head to knees, is again well preserved (Cairo, inv. No. JE 98181, excavation no. 770 / I / 84, 809 / I / 84, 853 / I / 84, 873 / I / 84, 979 / I / 84, 1020 / I / 84, 26 / I85). With dimensions of 49.3 cm × 14.82 cm × 18 cm, it represents the largest image of Raneferef. The ruler is shown standing in a standing-step position. He wears an apron and holds a club in front of his chest with his right hand while his left arm hangs down. He wears the white crown of Upper Egypt on his head . The beard was broken off when it was found, but has been completely preserved. The anatomical features of this statuette have been worked out very carefully. The collarbone is clearly visible and the nipples are shown in relief. From another standing and walking figure made of red quartzite (Cairo, without inventory number, excavation number 30 / I / 85, 64 / I / 85, 72 / I / 85) only five incoherent parts have survived , including a beard and remains of an Upper Egyptian crown.

Another seated statuette made of gray-black slate (Cairo, without inventory no., Excavation no. 855 / I / 84, 740 / I / 84), which has been preserved from head to hip, is also very carefully executed. It measures 23.8 cm × 17.3 cm × 10 cm. The king wears an apron, a beard and the Nemes headscarf . The arms originally rested on the thighs but broke off just below the crook of the elbows. The collarbones and nipples are clearly worked out.

Only the heads of two other statuettes made of gneiss , which also show Raneferef with a Nemes headscarf, have survived. The first (Cairo, without inv. No., Excavation no. 823 / I / 84) measures 8.5 cm × 10.9 cm × 10.1 cm. The eyes are not fully open on this head. The second (Cairo, without inv. No., Excavation no. 837 / I / 84, 27 / I / 85) measures 10.3 cm × 12 cm × 9.9 cm.

From another portrait, also made of gneiss (Cairo, without inventory number, excavation number 752 / I / 84) only the torso has survived. The piece measures 17.2 cm × 17.7 cm × 9.5 cm. The side flaps can still be seen on the chest and the plait of the Nemes headscarf on the back. A belt and part of the apron have been preserved at the waist. The arms are broken off above the elbows, but a seated statuette can probably be reconstructed with hands resting on the thighs.

Only the head of a statuette made of calcite (Cairo, without inventory number, excavation number 807 / I / 84, 829 / I / 84, 1057 / I / 84) has survived. It shows Raneferef again with a short hair wig. The dimensions are 9.8 cm × 6.3 cm × 7.2 cm. Eyebrows, eyelashes and eyelid lines are sculpted, a mustache is painted on.

Furthermore, fragments of four statue bases made of gneiss and calcite (Cairo, without inv. No., Excavation no. 782 / I / 84, 790 / I / 8, 852 / I / 84, 920 / I / 844) are known . The first measures 8.8 cm × 15.5 cm × 8.6 cm, the second 8 cm × 12.5 cm × 13.5 cm, the third 8 cm × 11.3 cm × 8.8 cm, and the fourth 11.8 cm x 10.1 cm x 14 cm. Three of these pieces show two feet placed side by side, so they should have belonged to seated statuettes. The fourth piece shows only one right foot. Finally, there is a fragment of an apron (Cairo, without inventory number, excavation number 67 / I / 85) and a fragment of the throne with the king's name (Cairo, without inventory number, excavation number 103 / I / 82).

In addition to the finds from Abusir, there is another statue head that possibly represents Raneferef. It comes from Koptos and is now in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archeology in London (inv.no. UC 14282). The piece is made of yellow limestone and measures 8 cm × 5.8 cm. The king wears a short-haired wig with the remains of a uraeus snake. The chin has not been preserved, but there are indications of an originally existing beard. The statue may have included a throne fragment found nearby, also made of yellow limestone. The piece was originally dated to the 4th Dynasty due to comparisons with portraits of Chephren and Mykerinos . The new finds from Abusir make a date in the 5th dynasty more likely, since the facial features and the headgear are more similar to the portraits of Raneferef than to those of the rulers of the 4th dynasty.

Raneferef in the memory of ancient Egypt

There is evidence of a death cult for Raneferef that lasted until the end of the Old Kingdom. Evidence for this comes from the reign of King Djedkare from the end of the 5th dynasty. At the end of the 6th dynasty under Pepi II, the cult of the dead dried up for the time being, but was briefly revived in the Middle Kingdom.

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 249-251.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 170-171.

To names

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , pp. 55, 182.

- Miroslav Verner : Un roi de la Ve dynastie. Rêneferef ou Rênefer? In: Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. (BIFAO). Vol. 85, 1985, pp. 281-284 ( PDF; 0.2 MB ).

To the pyramid

- Zahi Hawass : The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2003, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , pp. 249-251.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Econ, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 146-147.

- Miroslav Verner, Miroslav Bárta and others: Abusir IX: The pyramid complex of Raneferef: The archeology. (= Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. ) Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-200-1357-1 (the excavation report ).

- Miroslav Verner: The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 336-345.

For further literature on the pyramid, see Raneferef pyramid

To the sun sanctuary

- Miroslav Verner: The Sun Sanctuaries of the 5th Dynasty. In: Sokar No. 10, 2005, p. 44.

- Miroslav Verner: Remarques on the temple solaire [Hetep-Rê] et la date du mastaba de Ti. In: Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. (BIFAO). Vol. 87, 1987, pp. 293-297, ( PDF; 1.3 MB ).

- Susanne Voss: Investigations into the sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty. Significance and function of a singular temple type in the Old Kingdom. Hamburg 2004 (also: dissertation, University of Hamburg 2000), pp. 153–155, ( PDF; 2.5 MB ).

Questions of detail

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 27, 39, 153-155, 188.

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 62-69 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Paule Posener-Kriéger in: Egypt - Duration and Change. von Zabern, Mainz 1985, pp. 35-43.

- Paule Posener-Kriéger: Quelques pièces du matériel cultuel du temple funéraire de Rêneferef. In: Communication from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDAIK) No. 47, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 293–304.

- Dagmar Stockfisch: Investigations into the cult of the dead of the Egyptian king in the Old Kingdom. The decoration of the royal cult complexes. Volume 2. Kovac, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0857-0 , pp. 35-37.

- Eugen Strouhal, Luboš Vyhnánek: The identification of the remains of King Neferefra found in his pyramid at Abusir. In: Miroslav Bárta, Jaromír Krejčí (Eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute, Prague 2000, ISBN 80-85425-39-4 , pp. 551-560, ( Online version of the article in the Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt ).

- Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. (= Archive Orientální. Vol. 69) Prague 2001, pp. 363–418 ( PDF; 31 MB ).

- Miroslav Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 16 planches]. In: Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. (BIFAO) Vol. 85, 1985, pp. 267-280 with XLIV-LIX, ( PDF; 7.4 MB ).

- Miroslav Verner: Les statuettes en bois d`Abousir. In: Revue d'Égyptologie. (RdE) No. 36, 1985, pp. 145-152.

- Miroslav Verner: Supplément aux sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 4 planches] In: Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. (BIFAO) Vol. 86, 1986, pp. 361-366 with LXII-LXV, ( PDF; 1.7 MB ).

- Miroslav Verner et al .: Unearthing Ancient Egypt (Objevování starého Egypta) 1958–1988. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague 1990, pp. 33-38.

- Miroslav Verner: Who was Shepseskara, and when did he reign? In: Miroslav Bárta, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute, Prague 2000, ISBN 80-85425-39-4 , pp. 581–602.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Year numbers according to Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs.

- ^ A. Dodson , D. Hilton: The Complete Royal Families. Pp. 64-66.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. P. 338; M. Verner: Un roi de la Ve dynastie. Pp. 281-284.

- ↑ Silke Roth: The royal mothers of ancient Egypt from the early period to the end of the 12th Dynasty (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 46) Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7 , p. 106.

- ^ M. Verner: Who was Shepseskara. Pp. 595-596.

- ^ DD Baker: Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Vol. I, p. 250; M. Verner: Archaeological Remarks. Pp. 400-401.

- ^ M. Verner: Who was Shepseskara. Pp. 583-585.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Pp. 341-342.

- ^ M. Verner: Archaeological Remarks. P. 401.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. P. 337.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Pp. 338-340.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. P. 341.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. Pp. 341-345.

- ^ M. Verner: Sun sanctuaries. P. 44.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. P. 331.

- ↑ Silke Roth: The royal mothers of ancient Egypt from the early days to the end of the 12th dynasty. (= Egypt and Old Testament. Volume 46) Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7 , p. 105.

- ↑ M. Verner: The pyramids. P. 331.

- ↑ E. Strouhal, L. Vyhnánek: The identification of the remains of King Neferefra. Pp. 552-553.

- ↑ E. Strouhal, L. Vyhnánek: The identification of the remains of King Neferefra. P. 558.

- ↑ E. Strouhal, L. Vyhnánek: The identification of the remains of King Neferefra. Pp. 556-558.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. pp. 35–37; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 270-280.

- ↑ Hourig Sourouzian : The imagery of the Old Kingdom. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Sahure. Death and life of a great pharaoh. Hirmer, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7774-2861-1 , p. 82.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 35; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 272-273.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. pp. 35–36; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 272-273.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 36; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 274-275; M. Verner: Supplement aux sculptures de Reneferef. Pp. 361-363.

- ^ M. Verner: Supplement aux sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 364-365.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 36; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. P. 276.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 36; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. P. 277.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. pp. 36–37; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 277-278; M. Verner: Supplement aux sculptures de Reneferef. P. 363.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 37; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. P. 278.

- ↑ D. Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 37; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. P. 280.

- ^ D, Stockfisch: Investigations on the cult of the dead 2. p. 37; M. Verner: Les sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 279-280; M. Verner: Supplement aux sculptures de Reneferef. Pp. 363-364.

- ^ M. Verner: Supplement aux sculptures de Rêneferef. P. 363.

- ^ M. Verner: Supplement aux sculptures de Rêneferef. Pp. 365-366.

- ↑ Christiane Ziegler (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, pp. 316-317; UCL Petrie Collection Online Catalog .

- ^ T. Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. P. 171.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Neferirkare |

Pharaoh of Egypt 5th Dynasty |

Schepseskare |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Raneferef |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Neferefre, Nefer-ef-Re (throne name); Nefer-chau (Horus name); Ra-nefer-ef (other reading); Cheres (name of the king at Manetho) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king of the 5th dynasty (ruled around 2456 to 2445 BC) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 25th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 25th century BC Chr. |