Great Sphinx of Giza

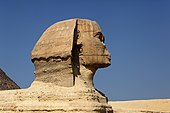

The (also the) Great Sphinx of Giza in Egypt ( Arabic أبو الهول, DMG Abū l-Haul ) is by far the most famous and largest sphinx . It depicts a reclining lion with a human head and was probably erected in the 4th dynasty during the reign of Chephren (around 2520 to 2494 BC, according to other sources 2570 to 2530 BC).

features

The Sphinx has protruded from the sand of the Egyptian desert for more than four millennia, most of the time it was covered up to the head in sand, which helped to preserve it.

The Sphinx is oriented in an east-west axis and consists of a human head on a lion's body, whereby the human head is too small in relation to the lion's body. The reason for this disproportion is unknown. Some researchers suggest that the Sphinx originally had a larger head and that today's head is a later change. Serves as evidence u. a. the Sphinx of Queen Hetepheres II from Abu Roasch , who was the daughter of Cheops at the same time. The fact that the head is less weathered than the body, although the body was buried in the sand for some time, but the head is not, supports this supposition. However, they could not clearly prove this thesis.

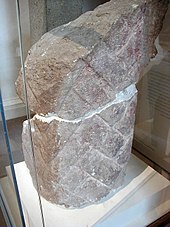

The head of the Sphinx is covered by a Nemes headscarf . The nose, like the goatee, is broken off. Pieces of the beard are now in the British Museum in London. The lion's body consists of a torso, front and rear legs, and a tail that winds around the thigh of the right hind leg. Today the Sphinx is about 73.5 m long and about 20 m high.

The Sphinx was carved from the remainder of a limestone mound that served as a quarry for the Great Pyramid of Cheops . As a result, it is located in a hollow that has been repeatedly filled with drifting sand over the course of time, which means that for centuries it often only protruded with its head over the sand. Paint residues on the ear suggest that the figure was originally painted in color, her body was covered with reddish ocher paint. Next to the Sphinx, a temple was built from the same stone, which is almost exactly in line with the valley temple of the Chephren pyramid and has a similar structure. Investigations by the geologist Thomas Aigner suggest that the stone blocks of the Chephren Valley Temple also consist of the same rock. Thus, both temples would have been built at the same time as the Sphinx.

The Sphinx has been restored several times. After its creation in the 4th dynasty, it was restored again by the 18th dynasty. The dating is from 1515 or 1415 BC. From what the reign of Amenhotep I , but more likely Amenhotep II , the son of Thutmose III. would correspond. The disproportionate head may have been reworked during this time. There is also evidence that parts of the paws have been restored.

Thutmose IV erected the so-called dream stele between the paws of the sphinx , the inscriptions of which tell of his life and his calling as pharaoh. Another restoration can be dated to the Greco-Roman period and again affects the paws of the Sphinx. It could come from the time of the Ptolemies and can also be proven by the bricks of that time. The Roman emperors Marcus Aurelius and Septimius Severus also had the sphinx freed from the sand and cleaned. In 1818 the Sphinx was exposed again by Caviglia. He also found fragments of the broken beard. He was followed by Émile Baraize and later by the Englishman Perring, who also carried out various drillings in search of secret chambers in the immediate vicinity of the Sphinx. Four shafts still bear witness to the attempts to discover the secret of the Sphinx. One of the shafts is behind the dream stele, a second on the back of the Sphinx. Two more lead from the side under the Sphinx. All shafts run into emptiness.

The penultimate restoration of the Sphinx was carried out in the 19th century at the time of Auguste Mariette and Gaston Maspero . The neck was reinforced with mortar because the head threatened to break off. Another crack ran through the body, which was filled with stone and sealed with mortar. Although the use of mortar and concrete has been heavily criticized, the Sphinx has preserved it for us in its current form. In addition, Mariette had a statue of Chephren transported from the lower valley temple to the Egyptian Museum he founded in Cairo, where it showed the Egyptians her great past for the first time. The last restoration took place in 1998 under the direction of Zahi Hawass and ended on May 25, 1998 with the ceremonial inauguration of the completely renewed Sphinx.

The condition of the trunk, which is more weathered than the head, is due to moisture damage as a result of Egypt's previously much rainier climate. In addition, as Thutmose IV noted on his dream stele, the Sphinx was repeatedly covered in sand for a long time, only the head peeped out.

Dimensions

The length of the Sphinx is around 73.5 meters, of which 15 meters are accounted for by the outstretched front legs. The face of the Sphinx is four meters wide, the head with a headscarf six meters. The height of the Sphinx is 20.2 meters.

function

What the Sphinx was used for is still unknown today. In Egyptology different opinions are represented. Perhaps she should guard the Giza plateau . Herbert Ricke said that the statue belonged to the sun cult and represents Harmachis , a local form of the sky god Horus . Perhaps the statue is also an image of the Pharaoh Chephren represented as Horus or an image of Cheops . Mark Lehner , who researched the Sphinx from 1979 to 1983, suspects Chephren as the builder, like other people. Rainer Stadelmann , on the other hand, preferred King Cheops. Using the most modern methods, other images and statues of these two pharaohs have been compared with the head of the Sphinx in recent years. A clear and unequivocal assignment has not been possible so far.

construction

The fact that the head of the Sphinx was only later placed on the lion's body has been scientifically refuted. The clear color differences are due to the different rock layers. Geologist Thomas Aigner identified the stones used for the Sphinx Temple with a location that is at chest level with the colossus. Blocks from the upper part of the Sphinx were used for the valley temple of Chephren. According to the researchers, the head has been redesigned several times over time.

Underground

Search bores in the bedrock of the Sphinx also investigated the assumption that there were previously undiscovered man-made structures under the statue. However, no artificially created cavities could be discovered. Since the Sphinx threatened to be severely damaged during one of these exploratory drillings, further activities of this kind were prohibited by the Egyptian Antiquities Authority (SCA).

excavation

Over time, the Sphinx has been cleared of sand several times. So by Thutmose IV , who then had the so-called dream stele set up between the front paws. Further purges took place under the Roman emperors Marcus Aurelius (161-180) and Septimius Severus (193-211).

In modern times, Giovanni Battista Caviglia was the first to have largely uncovered the Sphinx in 1816-1818 when he was looking for an entrance. Among other things, he found fragments of the beard, which are now exhibited in the British Museum . He was followed by the French engineer Émile Baraize , who exposed the Sphinx to the stone base between 1925 and 1926 and secured weathered parts with limestone and mortar. Further excavations were carried out by the Englishman John Perring , who carried out various drillings in search of secret chambers in the area. A decade after Emile Baraize, the Egyptian archaeologist Selim Hassan excavated a mud wall surrounding the Sphinx and found a brick with the inscription "Thutmose IV."

Chipped nose

The Sphinx got the name in Arab times أبو الهول / Abū l-Haul , which means “father of horror”. In one of his books, the Arab historian Al-Maqrīzī (1364–1442) reports that the devout sheikh of a Cairo Sufi monastery, Mohammed Saim el-Dar (Muhammad Şā'im ad-Dahr, German: “Someone who fastet ”) when a fanatical iconoclast chopped off the nose of the Sphinx in 1378 and was then killed by the angry crowd. The Arab historian and physician Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi (1161–1231), who came from Baghdad , indirectly confirmed this information through his description of the Great Sphinx and its magnificent nose in the 13th century. In the Middle Ages, the Sphinx was still worshiped as a god by parts of the population, and devout Muslims detested this cult .

The Danish artist Frederick Ludewick Norden (1708–1742) made in 1738 on the orders of his King Christian VI. Engravings of various Egyptian buildings. Among them was one with the buried Sphinx (Tête colossale du Sphinx) , which also shows the head without a nose (published in French in 1755). The rumor that Napoleon Bonaparte's soldiers or Turkish troops are said to have destroyed their noses during artillery exercises has thus been proven to be false. Napoleon was an enthusiast of Egypt who called this country the "cradle of the sciences and arts of all mankind" (l'Égypte - le berceau de la science et des arts de toute l'humanité) . Even then, the scientists who came to the country drew the Sphinx without a nose.

Trivia

There are various parodies about the incident of the missing nose. Probably one of the best known can be found in the volume Asterix and Cleopatra from the Asterix series, in which Obelix climbs onto the Sphinx and breaks off his nose under his weight.

In Las Vegas (Nevada, USA) there is a replica of the Sphinx in front of the Luxor Hotel / Casino .

Movies

- In the Sign of the Sphinx , ZDF Documentation, 2018

literature

- Michael Haase : Under the sign of Re . Herbig, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7766-2082-X .

- Selim Hassan : Excavations at Gîza VIII. 1936–1937. The Great Sphinx and its Secrets. Historical Studies in the Light of Recent Excavations . Government Press, Cairo 1953 ( PDF; 81.6 MB ).

- Selim Hassan: The Sphinx. Its History in the Light of Recent Excavations . Government Press, Cairo 1949 ( PDF; 22.1 MB ).

- Zahi Hawass : The Great Sphinx at Giza. Date and Function. In: Gian Maria Zaccone, Tomaso Ricardi di Netro (ed.): Sesto Congresso Internazionale di Egittologia. Atti . Volume II, Turin 1993, pp. 177-195 ( PDF; 9.9 MB ).

- Zahi Hawass: The Secrets of the Sphinx . American University in Cairo Press, Cairo 1998, ISBN 977-424-492-3 . ( PDF; 44.6 MB ).

- Peter Lacovara: The Pyramids, the Sphinx: Tombs and Temples of Giza. Bunker Hill Publishing, Boston 2004, ISBN 978-1-59373-022-2 .

- Ian Lawton, Chris Ogilvie-Herald: Giza: The Truth. The People, Politics and History Behind the World's Most Famous Archaeological Site. Virgin Publishing, London 1999, ISBN 0-7535-0412-X .

- Mark Lehner : Unfinished business reveals the human hand - The Great Sphinx: Why it is most probable that Khafre created the Great Sphinx. In: AERAGram - Newsletter of ancient Egypt Research Associates. Volume 5, No. 2, Spring 2002, pp. 10-14 ( PDF; 27.6 MB ).

- Mark Lehner: Secret of the Pyramids . Bassermann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8094-1722-X .

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 .

- Christiane Zivie-Coche: Sphinx . Primus, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-89678-250-9 .

Web links

- Extensive information and photos of the Sphinx ( Memento from October 10, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Summary of the scientific discussion about the age of the Sphinx (private page)

- Brief summary information ( Memento of December 10, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ The Sphinx Project: Puzzles come in pieces . From aeraweb.org , accessed August 7, 2015.

- ↑ so after Thomas Schneider : Lexikon der Pharaonen . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 102-103.

- ^ A b Charles Rigano: Pyramids of the Giza Plateau: Pyramid Complexes of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. AuthorHouse, 2014, ISBN 978-1496952493 , p. 148. ( limited preview in Google Book Search)

- ↑ Great Sphinx of Giza . On: emporis.com ; last accessed on February 23, 2018.

- ^ Stefan Eggers: Sphinx of Giza. On: pyramidenbau.info ( Memento from July 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sphinx . On: ancient-cultures.com ; last update March 23, 2019; last accessed on March 25, 2019.

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley : Myth of Egypt. The story of a rediscovery. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-15-010598-6 , p. 46.

- ↑ see Norden, 1755: The Great Sphinx of Gizeh

Coordinates: 29 ° 58 ′ 31 ″ N , 31 ° 8 ′ 15 ″ E