Amenemhet I pyramid

| Amenemhet I pyramid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

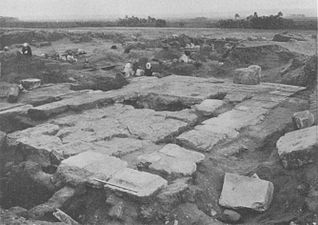

The pyramid of Amenemhet I.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Amenemhet I pyramid ( ancient Egyptian Chau-isut-Imen-em-hat ) is the tomb of the ancient Egyptian king Amenemhet I , the founder of the 12th dynasty in the Middle Kingdom . Construction began in the first year of Amenemhet I's reign (circa 1939/38 BC). He chose el-Lisht as the location and thus founded a new royal necropolis in the immediate vicinity of the new capital Itj-taui ("Who seizes the two countries") halfway between Dahshur and Meidum . The main reason for the relocation of the capital from Thebes to the interface between the two countries of Upper and Lower Egypt was certainly the control over the strong regional principalities that had existed up until then . With a side length of 84 meters and an incline of 54 ° 27 ', the pyramid was 59 meters high.

Research history

The first documentation of the pyramid was carried out by John Shae Perring in 1839 . The publication took place in 1842 by himself and by Richard William Howard Vyse . Carl Richard Lepsius visited el-Lischt during his Egypt expedition 1842-1846 and documented the ruins there between March and May 1843. He added the Amenemhet I pyramid to his list of pyramids under the number LX .

Gaston Maspero was the first to enter the pyramid in 1882. The first systematic excavations took place in 1894/95 under Joseph-Étienne Gautier and Gustave Jéquier . Between 1906 and 1934, a research team from the Metropolitan Museum of Art dug in Lischt in 14 campaigns. Five of them, under the direction of Albert M. Lythgoe (1906–1914) and Arthur C. Mace (1920–1922), applied to the Amenemhet I pyramid, although no publications except preliminary reports appeared at that time. The campaign planned for 1922/23 was canceled at short notice, as Mace and a large part of the rest of the excavation team were recruited by Lord Carnavon to support Howard Carter with the uncovering and documentation of the recently discovered tomb KV62 of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor . Since Mace's health deteriorated significantly in the following years, the excavations at the Amenemhet I pyramid were not resumed for the time being. A subsequent excavation was only carried out in 1991 under the direction of Dieter Arnold . A complete publication of the excavations of the Metropolitan Museum appeared in 2016 in the form of a volume by Dieter Arnold on the architecture of the pyramid complex and another volume by Peter Jánosi on the reliefs.

Surname

A distinctive feature of the 12th Dynasty pyramids is the use of different names for different parts of the pyramid complex. While the facilities of the Old Kingdom only had one name for the entire royal tomb complex, the facilities of the 12th Dynasty had up to four names, which denoted the actual pyramid, the mortuary temple, the cult facilities of the district and the pyramid city. Two names have been passed down for sure for the Amenemhet I pyramid: the actual pyramid was named Chau-isut-Imen-em-hat (“The sites of Amenemhet appeared”), the cult complex was called Qa-nefer-Imen-em -hat (“Amenemhet is high in perfection”). The assignment of the name Ach-iset-ib-Imen-em-hat (“Transfigured is the heart of Amenemhet”) to the mortuary temple is uncertain. The pyramid city was possibly identical to the residence and therefore perhaps had the two name variants Imen-em-hat-jtj-taui ("Amenemhet seizes the two lands") and Sehetep-ib-Re-jtj-taui ("Sehetepibre [ throne name Amenemhets I .] seizes the two countries ”).

Construction details

In contrast to the pyramid of his son Sesostris I , significantly fewer control marks of the ancient Egyptian craftsmen have survived from the Amenemhet I pyramid . Only three of them have dates and only one of them has the year. It comes from the first year of Amenemhet I's reign, which at least proves that the king began building his pyramid complex immediately after he ascended the throne.

The pyramid

The superstructure

With his pyramid, Amenemhet I resumed the shape of the buildings of the late Old Kingdom, but also took up the tomb architecture of the 11th Dynasty by erecting it on a two-tier terrace. The pyramid has a side length of 160 cubits (84 m) and an angle of repose of 54 ° 27 '. Its original height was thus about 59 m, due to massive stone robbery its current height is only between 20 and 25 m. The inner structure of the pyramid has so far only been insufficiently researched. According to Lepsius, it must have had a five-step core around which cloaks were placed. The only building material used for the core was local limestone, sand and rubble to fill the cavities. The assumption originally expressed by Lepsius and often adopted that bricks were also used is based on a misinterpretation of the findings. In fact, these come from buildings later built on the ruins of the pyramid. Quality Tura limestone was used for the cladding .

Numerous reliefs from the Old Kingdom were also found in the rubble of the pyramid. Amenemhet I had these brought in from the pyramid districts or from other buildings by Cheops , Chephren ( 4th dynasty ), Userkaf , Unas ( 5th dynasty ) and Pepi II ( 6th dynasty ), which is evidenced by corresponding names. The exact reasons for this are unclear, partly because most of the blocks were no longer found in their original context. Other blocks from the Old Kingdom were discovered in the foundations of the mortuary temple (see below).

Foundation deposits

It is possible that foundation deposits were created under all four corners of the pyramid. Corresponding depots were found under three corners of the better documented Sesostris I pyramid. In the case of the Amenemhet I pyramid, on the other hand, only the southwest corner was exposed during the Metropolitan Museum's excavation season 1920/21. A pit was discovered that was covered with a limestone slab and filled with white sand. It had a rectangular cross section on the surface and an oval cross section on the bottom. After the backfill was removed, the foundations came to light. They consisted of a cattle skull , six clay bricks and badly shattered ceramic vessels , which could still be reconstructed into plates and vases . Since the clay bricks were broken, it was discovered that they were enclosed in small tablets bearing the name of Amenemhet I and that of his pyramid. Two of the panels were made of copper , two of faience and one of limestone. The sixth panel - probably also made of limestone - was missing. Excavation supervisor Arthur C. Mace suspected that it was stolen by one of the workers during the excavation.

North chapel and entrance area

As with the systems of the Old Kingdom, the entrance to the pyramid is centrally located on the north side at ground level. There was a north chapel above the entrance . No traces of this have been preserved. Two remarkable finds at the entrance area represent a large false door made of rose granite and a granite pavement , both of which were built in as spoilers . About two thirds of the false door that is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Inv.No. JE 40485) has been preserved. It has a height of 3.86 m, a width of 2.20 m and a depth of 0.83 m. Their original width should have been around 3.30 m. It is thus the largest known false door from all Egyptian pyramid complexes. Although the inscriptions were chiseled out, traces of Amenemhet I's names can still be made out. Presumably it originally stood in the mortuary temple and was then replaced by a smaller stone door made of limestone for unknown reasons (perhaps because it broke) and reused as a ceiling block for the descending corridor.

The second spoil is a granite pavement that was used as a floor slab at the entrance to the pyramid. It has a width of 3.05 m, a preserved depth of 2.10 m and a thickness of 0.85 m. The weight of the stone is about 15 t. The original top is now down. Dieter Arnold was able to prove that it was originally a threshold stone from a north chapel of the Old Kingdom, which was laid between its entrance and the access to the chamber system located in the ground. An entrance in the courtyard with a chapel built above is an architectural feature that only applies to the pyramids of the late 5th dynasty (from Djedkare ) and the 6th dynasty . However, it has not yet been possible to assign it to a specific pyramid.

The chamber system

From the north chapel, a descending corridor leads diagonally downwards. It is clad in rose granite and sealed with stones of the same material along its entire length. Directly below the center of the pyramid it opens into a small granite-clad chamber. It has a rectangular floor plan and a flat ceiling. Its length is 2.63 m, its width 1.14 m and its height 1.45 m. Along the western outside of the descending corridor, a tomb robber tunnel leads through the softer limestone into the chamber. From the middle of the chamber floor, a square shaft with a side length of 0.75 m leads at least 11 m vertically into the depth. Due to the presence of groundwater, it has not yet been researched in more detail. This and the fact that such a chamber system differs significantly from the models of the Old Kingdom also creates confusion about the actual burial chamber. While Dieter Arnold considers the investigated chamber to be the burial chamber, other researchers such as Mark Lehner , Rainer Stadelmann or Miroslav Verner see it merely as an antechamber and assume that the chamber system is based on Theban models of the 11th dynasty and that the burial chamber is thus still undiscovered at the end of the vertical shaft.

The pyramid district

The pyramid was surrounded by two walls. The inner limestone wall encompassed the building itself and the mortuary temple in the east in front of it .

The outer perimeter wall and the outer courtyard

The outer wall made of mud bricks included the pyramid and the mortuary temple, a few mastabas and 22 shaft graves in which family members and courtiers were buried. There was a sacrificial tablet with the name of the “ king mother ” Nofret and the mastabas of the vizier Antefiqer , the treasurer Rehuerdjersen and the senior property manager Nacht . In the mastaba area of Sesostris next to the pyramid there was a shaft grave with the untouched burial of Senebtisi , which still contained rich jewelry. The grave dates to the end of the 12th dynasty.

The mastabas in the outer courtyard

The outer enclosing wall of the royal pyramid includes six large mastaba tombs. To the north of the mortuary temple are the remains of two very similar structures. The western of them, grave 954, was extensively documented by the Metropolitan Museum expedition in 1921/22. It has an enclosure made of bricks measuring 18.50 × 22.20 m. In the northern area a 2.80 × 3.00 m wide shaft leads about 3 m into the depth and branches out there. A corridor leading from the southwest corner leads into the groundwater and has not yet been investigated in more detail. Another shaft was dug at the eastern end, probably afterwards. This measures 1.00 × 2.15 m and has a depth of 15.70 m. It has three levels of six coffin niches each, which branch off from the shaft in a north and south direction. All twelve niches on the two upper levels were occupied, the lower ones, however, remained unused. The burials were found untouched and contained numerous jewelry in the form of collars , chains , bracelets and anklets as grave goods . Only one coffin had the name of its owner, a woman named Sat-Sobek, on it. Dating the complex is difficult. One of the burials was dated to the early 12th dynasty based on the grave goods, the architecture, however, fits more into the 13th dynasty .

The grave 956 to the east has already been examined by Gauthier, who, however, did not make any plans or photos. The Metropolitan Museum team did not conduct a follow-up examination. The plant has a brick enclosure of 22.60 m length, 16.00 m width and a wall thickness between 3.30 and 3.40 m. Dieter Arnold estimates its original height to be at least 6.20 m (12 cubits). A large accumulation of limestone within the enclosure was only documented photographically. This could have been the former core building of the mastaba. According to Gauthier, the courtyard paving was also made of limestone. A cult chapel occupied the western part of the courtyard. At its northern end, a 1.30 × 3.20 m shaft leads straight down. Because of the penetration of groundwater, it has not yet been examined more closely.

South of the mortuary temple is the grave of the vizier and mayor of the pyramid city Antefiqer, who served under Amenemhet I and Sesostris I. The grave, which is comparatively small for such a senior official, is divided into two roughly equal areas. The eastern half forms an open courtyard, which was enclosed by a brick wall with a thickness of 1.50 m. The western half of the complex was formed by a chapel, the entrance front of which was about 9.20 m wide. It consisted of three rooms: an elongated, north-south oriented entrance hall, an east-west oriented hall going south from it and a hall going west in which the grave shaft was located. The southern hall had a false door on its west wall . Another false door was on the south wall of the shaft chamber. Remnants of the wall decoration were also discovered, including a slaughtering scene. Since the excavations in the early 20th century, the mastaba's superstructure has been almost completely removed. The grave shaft measures 1.70 × 3.00 m. It was only explored to a depth of 12.5 m, as groundwater has prevented further penetration so far. The shaft was clad with limestone to a depth of 3 m, after which it led through the surrounding rock. A second shaft in the open courtyard. It measures 1.20 × 1.50 m and has not yet been explored because of groundwater. Two statues of Antefiqer were found in the tomb complex, their current location is unknown. A third statue represents another Antefiqer, son of the Nebit. It originally came to the Metropolitan Museum, but was later given to the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas .

The southeast corner of the outer courtyard is occupied by the extensive grave complex of the chief asset manager and seal keeper Nacht, who presumably held office during the reign of Sesostris I. As early as the 13th dynasty, the grave was severely damaged by the overbuilding with houses, so that its original structure is difficult to reconstruct. The complex was probably modeled on Theban terrace temples. It had a lower outer perimeter wall and a higher inner wall. Both were made of bricks. A ramp or an access road made of bricks led from the east over a distance of about 20 m to the actual mastaba. Since the difference in level between the beginning and the end of the ramp is only very small, it is unclear whether it was deliberately designed for the tomb or whether Nacht had merely reused the remains of a construction ramp of the royal pyramid. The outer perimeter wall formed a forecourt originally 12 m wide, which was later expanded to 22.50 m. The inner perimeter wall was 1.9 m thick on the sides and perhaps between 2 and 3.5 m high. The east side was 2.5 m thick and possibly formed a pylon at least 5 m high. The cult chapel, which formed the superstructure of the tomb, was oriented east-west and measured 11.90 × 6.70 m. A portico with two columns was in front of its entrance. The interior of the chapel can no longer be completely reconstructed, only a 3 × 5.80 m room and a narrow chamber or an open corridor could be identified. Only small remains of the wall decoration were found. A life-size seated statue of the tomb owner is an important find. Two heavily damaged statue heads could originally have belonged to the royal mortuary temple. A statuette found relocated could again represent night. The chamber system of the tomb is quite complex. A funeral shaft measuring 1.05 × 1.05 m to the north-east of the chapel leads 14 m into the depth and there opened into a chamber that was used by workers. Three locking stones were found there. A 6 m long corridor leads from there to the southwest under the center of the chapel. There it opens into a chamber which has bulges with locking stones that are not in position. Above the chamber there is a vertical construction shaft, the upper end of which was closed by the construction of the chapel. A descending corridor leads from the chamber in a south-westerly direction to the burial chamber, which has not yet been examined due to groundwater. At the lower end of the construction shaft on the southeast side there is a 1 m high and 2.4 m long niche of unknown function. From the northwest wall of the corridor, a 12.3 m long descending corridor leads into a 1.9 × 2.6 m rock chamber. At the lower end of the funeral shaft, five coffin niches were added to the east and west. A 6.5 m long corridor was also added on the north side. Fifteen secondary grave shafts were found in the two courtyards of the tomb: nine in the inner courtyard and six in the outer courtyard.

To the west of the mastaba of the night and south-east of the pyramid is the grave of the keeper of the seals Senimeru, who probably served under Amenemhet I or Sesostris I. The grave was surrounded by a brick wall, which was 1.60 m thick on the east and west sides, but 3.20 m thick in the north and south. The superstructure of the mastaba was a north-south oriented building of 9.8 × 13 m, the exact structure of which is unknown. After the excavation in 1914, its remains were completely removed. The grave shaft measures 1.30 x 2.65 m and is 13.1 m deep. From there a descending corridor leads to the burial chamber. Since no cardinal points were given on the excavation plans, it is unclear whether it leads north or south, but the latter is more likely based on comparisons with other graves, but the sarcophagus would then be on the east wall of the burial chamber, which again would be unusual. The corridor is 5.4 m long and has three blocking stones. Apparently there is a tomb robber tunnel with which the blockage was bypassed. The burial chamber measures 2.25 × 3 m and has a height of 1.75 m. Half of it was flooded by groundwater during the excavation. On the narrow sides there are niches that made it possible to insert the sarcophagus. This is made of rose granite and has a length of 240 cm, a width of 75 cm and a height of 81.5 cm. The lid is arched and 23 cm high. The inside of the sarcophagus was covered with plaster .

In the southwest corner of the outer courtyard is the mastaba of the treasurer Rehuerdjersen, who probably served under Amenemhet I. The grave had a wall made of bricks with a north-south length of 27.70 m, an east-west width of 19 m and a wall thickness of 3 m. The interior consisted of a large open courtyard to the north and a series of six rooms along the south side that served as priestly quarters. A perforated copper container was found in one of the rooms, which probably served as a sprinkler. To the northwest of the enclosure wall is a narrow staircase, of which it is unclear whether it belongs to the grave and was only created later when the pyramid complex was used as a settlement. The cult chapel in the open courtyard had a core of field stones and a cladding of limestone. In the south, the chapel had two rooms: an entrance hall 3.42 m long and 2.04 m wide with a statue niche on the west wall, and a sacrificial hall to the north, 4.97 m long and 2.26 m wide. Numerous relief fragments of the original wall decoration were found. It was also found that limestone blocks from buildings from the Old Kingdom, one of which bears the name of Cheops, were reused for the foundations of the chapel. The position of the grave shaft is unusual for a Mataba of the Middle Kingdom and is probably based on models from the Old Kingdom from Giza . It leads from the northern part of the chapel roof first vertically and then at a very steep angle downwards. Groundwater at a depth of around 17.70 m prevented further investigation. Foundations containing numerous ceramic vessels were discovered under all four corners of the mastaba foundation and under the west wall of the chapel. 14 secondary burial shafts were found in the courtyard and the southern rooms.

The shaft graves of the princesses

Two almost regular rows of eleven shaft graves each run along the western outside of the inner enclosure wall. Only the second grave in the western row, seen from the south, is slightly offset to the east. The individual shafts are spaced between 5 and 6 m apart. The eastern graves, with the exception of the southernmost, were carefully executed. The shafts led to a depth of about 10 m and there opened into individual burial chambers, which had a recess in the ground to accommodate the sarcophagus. The other shafts were much more coarse and had up to 16 chambers. This led the excavators to hypothesize that the eastern tombs were intended for the female members of the royal family while the western tombs were intended for their servants. Since all graves were looted and even the sarcophagi removed, it is no longer possible to reconstruct which shaft grave was intended for whom. A stone fragment with the name of the king's daughter Neferu (III.) And a granite weight with the name of the king 's daughter Neferuscheri were found in the upper fillings of two shafts . Neferuscheri could have been buried in the pyramid district. For Neferu (III.), On the other hand, the wife of Sesostris I and mother of Amenemhet II, a pyramid was erected in the burial area of her husband. Burial at her son's pyramid is also being considered. An altar of the king's mother Nefertiti reused in a house suggests that the mother of Amenemhet I was also buried in one of the shafts. Another relief fragment from Lischt calls for a king's daughter named Kaiet . In a shaft the excavators found a large gold tube from a bracelet that the grave robbers had overlooked.

The mortuary temple

This was on a terrace that had been cut into the hill on which the pyramid stood. Perhaps the terrace temple of Mentuhotep II in Deir el-Bahari served as a model here. The temple itself has been completely destroyed; only foundation deposits, a false door and a granite altar were found. The altar shows figures who, as emissaries of the Egyptian Gaue (the king?), Make sacrifices. The way from the valley temple to the mortuary temple was not covered and also consisted of richly decorated limestone masonry. The reliefs deliberately imitate the style of the Old Kingdom and can hardly be distinguished from them. The valley temple is under water and has therefore not yet been documented.

literature

General overview

- William C. Hayes : The Scepter of Egypt. A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1. From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1978, ISBN 978-0870991905 , pp. 171-179 ( online ).

- Peter Jánosi : The pyramid district of Amenemhets I in Lisht. In: Sokar. Volume 14, 2007, pp. 51-59.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. ECON, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 168-170.

- Bertha Porter , Rosalind LB Moss : Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. IV. Lower and Middle Egypt (Delta and Cairo to Asyût). Griffith Institute, Oxford 1968, pp. 77-81 ( PDF; 14.3 MB ).

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 233-234.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 434–437.

Excavation publications

- Dieter Arnold : Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 28). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2008, ISBN 978-1-58839-194-0 ( online ).

- Dieter Arnold: The Pyramid Complex of Amenemhat I at Lisht. The Architecture (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 29). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-58839-604-4 .

- Felix Arnold : The South Cemeteries of Lisht II. The Control Notes and Team Marks (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 23). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1990, ISBN 978-0-30009-161-8 ( online ).

- Peter Jánosi: The Pyramid Complex of Amenemhat I at Lisht. The Reliefs (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 30). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-58839-605-1 .

- Albert M. Lythgoe : The Egyptian Expedition. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 2, No. 4, April 1907, pp. 60-63 ( JSTOR 3253285 ).

- Albert M. Lythgoe: The Egyptian Expedition. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 2, No. 7, July 1907, pp. 113-117 ( JSTOR 3253292 ).

- Albert M. Lythgoe: The Egyptian Expedition. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 2, No. 10, October 1907, pp. 163-169 ( JSTOR 3253176 ).

- Albert M. Lythgoe: The Egyptian Expedition. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 3, No. 5, May 1908, pp. 83-86 ( JSTOR 3253348 ).

- Arthur C. Mace : The Egyptian Expedition: III. The Pyramid of Amenemhat. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 3, No. 10, October 1908, pp. 184-188 ( JSTOR 3252551 ).

- Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: Excavations at the North Pyramid of Lisht. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 9, No. 10, October 1914, pp. 203, 207-222 ( JSTOR 3254066 ).

- Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: 1920-1921: I. Excavations at Lisht. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 16, No. 11/2, November 1921, pp. 5-19 ( JSTOR 3254484 ).

- Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: Excavations at Lisht. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Tape. 17, No. 12/2, December 1922, pp. 4-18 ( JSTOR 3254276 ).

- Gaston Maspero : Étude de mythologie et d'archéologie égyptiennes. Volume 1, Paris 1893, pp. 148-149 ( online ).

- William Kelly Simpson : The Pyramid of Amen-em-het I at Lisht: The Twelfth Dynasty Pyramid Complex and Mastabehs. Dissertation, Yale 1954.

Questions of detail

- Hartwig Altenmüller : The pyramid names of the early 12th dynasty. In: Ulrich Luft (Ed.): The Intellectual Heritage of Egypt. Studies Presented to László Kákosy (= Studia Aegyptiaca. Volume 14). Budapest 1992, ISBN 963-462-542-8 , pp. 33-42 ( online ).

- Dieter Arnold: A lost pyramid? In: Nicole Kloth , Karl Martin , Eva Pardey (eds.): It will be put down as a document. Festschrift for Hartwig Altenmüller on his 65th birthday (= studies on ancient Egyptian culture. Supplement 9). Buske, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 978-3-87548-341-3 , pp. 7-10 ( online ).

- Felix Arnold: Settlement Remains at Lisht-North. In: House and Palace in Ancient Egypt (= investigations by the Cairo branch of the Austrian Archaeological Institute. Volume 14 / Memoranda of the entire Academy. Volume 14). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1996, ISBN 978-3-7001-2209-8 , pp. 13-21 ( online ).

- LM Berman: Amenemhat I. Dissertation, Yale 1985.

- Henry George Fischer : Offering Stands from the Pyramid of Amenemhet I. In: Metropolitan Museum Journal. Tape. 7, 1973, pp. 123-126 ( online ).

- Hans Goedicke : Re-used Blocks from the Pyramid of Amenemhet I at Lisht (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 20). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1971, ISBN 0-87099-107-8 ( online ).

- Peter Jánosi: The secret of the old kingdom spolia in the pyramid of Amenemhet I. In: Sokar. Volume 17, 2008, pp. 58-65.

- Adela Oppenheim : In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.): Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1999, ISBN 0870999060 , pp. 318-327 ( online ).

- James M. Weinstein: Foundation Deposits in Ancient Egypt. Dissertation, Ann Arbor 1973.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Years after Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , p. 52.

- ↑ John Shae Perring, EJ Andrews: The Pyramids of Gizeh. From Actual Survey and Admeasurement. Volume 3, Fraser, London 1843, p. 19, plate 17 ( online ).

- ^ John Shae Perring, Richard William Howard Vyse: Operations carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837: With an Account of a Voyage into Upper Egypt, and Appendix. Volume 3, Fraser, London 1842, pp. 77-78 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia. Text. First volume. Lower Egypt and Memphis. Edited by Eduard Naville and Ludwig Borchardt, edited by Kurt Sethe. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1897, pp. 212-215 ( online ).

- ↑ Gaston Maspero: Étude de mythologie et d'archéologie égyptiennes. Volume 1, Paris 1893, pp. 148-149 ( online ).

- ↑ Joseph Étiennte Gautier, Gustave Jéquier: Fouilles de Lisht. In: Revue archéologique . Ser. 3, Vol. 29, 1896, pp. 39-70 ( online ).

- ^ Dieter Arnold: The Pyramid Complex of Amenemhat I at Lisht. The Architecture. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2016.

- ↑ Peter Jánosi: The Pyramid Complex of Amenemhat I at Lisht. The reliefs. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2016.

- ↑ Hartwig Altenmüller: The pyramid names of the early 12th dynasty. 1992, pp. 33, 35-36, 41.

- ^ Felix Arnold: The Control Notes and Team Marks. 1990, pp. 61-62.

- ↑ a b c Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. 1991, p. 233.

- ↑ Verner: The pyramids. 1999, p. 509.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. 1999, p. 435.

- ^ Peter Jánosi: The pyramid complex Amenemhet I in Lisht. 2007, p. 57, note 10.

- ↑ Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia. Text. First volume. Lower Egypt and Memphis. Edited by Eduard Naville and Ludwig Borchardt, edited by Kurt Sethe. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1897, pp. 212-215 ( online ); Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. 1991, p. 234; Mark Lehner: Secret of the Pyramids. 1997, p. 168; Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. 1999, p. 435.

- ^ Peter Jánosi: The pyramid complex Amenemhet I in Lisht. 2007, p. 57, note 8.

- ^ Peter Jánosi: The pyramid complex Amenemhet I in Lisht. 2007, pp. 54-55.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: The Pyramid of Senwosret I (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 22). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1988, ISBN 0-87099-506-5 , pp. 87-90 ( online ).

- ^ Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: 1920-1921: I. Excavations at Lisht. 1921, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Peter Jánosi: The pyramid complex Amenemhet I in Lisht. 2007, pp. 52-53.

- ^ Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: III. The Pyramid of Amenemhat. 1908, p. 187.

- ↑ Dieter Arnold: A lost pyramid? 2003, pp. 7-10.

- ^ Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: III. The Pyramid of Amenemhat. 1908, pp. 186-187.

- ^ Peter Jánosi: The pyramid complex Amenemhet I in Lisht. 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ Mark Lehner: Secret of the pyramids. 1997, p. 168.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. 1999, p. 436.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, pp. 82-83.

- ^ Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: Excavations at Lisht. 1922, pp. 6-10.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, pp. 83-84.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, pp. 69-71.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, pp. 72-77.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, pp. 71-72.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht. 2008, pp. 63-69.

- ^ Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: 1920-1921: I. Excavations at Lisht. 1921, p. 15.

- ^ A b Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: Excavations at Lisht. 1922, p. 12; William C. Hayes: The Scepter of Egypt 1. 1978, pp. 176-177.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004, ISBN 977-424-878-3 , pp. 92, 97.

- ^ Arthur C. Mace: The Egyptian Expedition: Excavations at Lisht. 1922, p. 12; William C. Hayes: The Scepter of Egypt 1. 1978, p. 177.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004, ISBN 977-424-878-3 , pp. 92, 96.

Coordinates: 29 ° 34 ′ 29.2 ″ N , 31 ° 13 ′ 30.3 ″ E