Craft

As craft (from Middle High German hant-werc , a loan translation to Latin opus manuum and ancient Greek χειρουργία cheirurgía "handicraft") are numerous commercial activities that usually manufacture products to order or provide services on demand. The term also describes the entire profession . The craft activity is opposed to the industrial mass production . The craft trade is regulated in Germany by the craft regulations.

history

Antiquity

In Classical Greece , craftsmanship ( téchnai banausikaí , hence our current word “ banause ”) was not particularly valued , especially in the larger pole ice . Xenophon wrote in his Oikonomikós (4, 2-3):

- “Because it is precisely the so-called manual professions that are disreputable and for good reason are particularly despised in the cities. Namely, they harm the bodies of workers and overseers by forcing them to sit and work under one roof; some even compel them to spend the whole day in front of the fire. But once the body has become effeminate (literally: feminized, i.e. with the light skin color of those working in the house), the souls also become more susceptible to diseases. The so-called manual trades also allow the least amount of free time to look after friends or the city, so that such people seem to be useless for socializing and for the defense of the fatherland. Consequently, in some cities, but especially in those that are considered to be able to fight, no citizen is allowed to work in manual trades. "

His main argument against the craft is working inside a workshop, which he equates with activities of a woman within the house. Practicing a craft disqualifies the craftsman for military service; so he cannot defend his polis. In addition, according to Xenophon, there is no free time left in a craft that one could spend on friends or other activities for the polis.

Plato, on the other hand, sees the craftsman in his work Politeia (601c – 602a) too dependent on the consumer:

- "But now the quality and the beauty and the correct constitution of every device and object as well as living being does not refer to anything other than the use for which every one is manufactured or naturally produced." - "So that is also necessary The user is always the most experienced and he has to report to the manufacturer how what he uses shows up well or badly in use. How the flute player has to tell the flute maker about the flutes, which serve him well with the flute, and how he should make them, but he has to obey. ”-“ Of course. ”-“ So the one who knows states what good and bad flutes are, but the other person makes them as a believer? ”-“ Yes. ”-“ So the manufacturer has a correct belief of the same device, whether it is good or bad, because he works with the knower bypasses and is compelled to listen to this knower; but the user has the science of it. "

Because of this dependency, the craftsman for Plato cannot be “free” in the true sense of the word, and thus receives a status similar to that of a slave.

Finally, in his book Politics (1328b – 1329a) , Aristotle even goes so far as to say that a polis can only be happy if none of its citizens have to practice a craft:

- "Since we are now asking about the best constitution, that is, the one with whom the city is happiest, and since we stated earlier that happiness cannot exist without virtue, it is clear that in the best-administered city, its citizens that is, absolutely and not only under certain conditions, these are not allowed to lead the lives of craftsmen or traders. Because such a life is ignoble and contradicts virtue. "

Nevertheless, there is no general contempt for the craft. Xenophon recognized the advantages of specialization and the division of labor in his work Kyrupädie (VIII 2, 6–7):

- “Just as the various handicrafts are most highly developed in the big cities, the König's dishes are particularly well prepared in the same way. In the small towns the same people make a bed, a door, a plow, a table, and often the same man builds houses and is satisfied if he can only find enough work to support himself. But now it is impossible for a person who does a lot to do everything well. In the big cities, however, a handicraft is enough for everyone to support themselves, since many need every thing. Often less than a whole craft is enough: For example, one person makes shoes for men, the other for women. There are also places where one lives solely from repairing shoes, another from cutting them to size, still another just from sewing the upper leathers together, and finally one who does none of this, but joins these pieces together. It is now imperative that those who work in a small area can do their work best. "

middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages , which was largely dominated by the peasantry, handicraft activities that later became specialized, such as the processing of food, the manufacture of textiles or the manufacture of appliances and buildings made of wood, played a negligible role compared to domestic production. Special work techniques, such as bronze casting, painting and sculpture, were tied to monasteries. Only in the High Middle Ages and with the development of cities did urban centers regain their ancient importance. The goods produced were offered for sale in markets or exhibited and sold in workshops and shops . Master builders and stone masons played an exceptional role, moving from one (church) building hut to the next, spreading skills, innovations and style developments across territorial borders.

Important craft professions were blacksmith or potter , whose activities required extensive equipment even then. The cultural development of urban life was accompanied by a diversification of textile production and leather processing, goldsmiths , cabinet makers and pewter founders produced special craftsmanship. Until the end of the Middle Ages, individual trades of the urban craftsmen formed self-governing guilds. Next to them there were few vacant commercial and individual, from the guilds liberated free master , but many secretly working in the suburbs and attics artisans who were persecuted by the corresponding guild masters. The political power sharing of the artisans in the developing urban bodies was very different in the German-speaking area, but those communal constitutions predominated in which property-owning and trading families had the say.

The so-called " artes mechanicae ", the practical arts , included seven different crafts in the European Middle Ages:

- vestiaria (clothing trade, i.e. tailors , tanners , weavers )

- agricultura ( agriculture )

- architectura ( building trade , i.e. stonemasonry , bricklaying , carpentry )

- militia and venatoria (the former martial arts and weapon knowledge, the latter the hunting trade )

- mercatura ( trade and commercial activities)

- coquinaria ( culinary art )

- metallaria ( blacksmithing , metallurgy )

The German saying handicraft has golden ground comes from the Middle Ages , the saying goes completely handicraft has golden ground, said the weaver, as the sun shone in his empty bread bag. The saying was sarcastically applied to the poverty of many small master craftsmen, especially weavers.

In the Tyrolean open-air museum Knappenwelt Gurgltal , original handicrafts from the Middle Ages are presented at the annual handicrafts workshop, including a. Pottery, forging, wool processing and bow making.

Early modern age

From the 16th to the 18th century who took professional rules, for example, to apprenticeship, to learn the hard way , the journeyman, the roller or the master exam to continue with the increase in the complexity of professional concepts and the progressive specialization. The contemporary class literature recorded the most important handicrafts, activities, work items and tools . Wandering journeymen learned, handed down and spread different working techniques. In addition, the Walz brought about a certain level of labor market compensation. Work certificates of the craftsmen were often calligraphically artfully designed craft customers. Handicraft literally had a golden base. The choice of profession was mostly made according to the status of the class . Women, Jews, people born out of wedlock and the descendants of so-called dishonorable people (e.g. hangman's children) were often denied access to traditional handicrafts. In guild craft businesses, however, the master's wives played an important role - as demonstrated by the carpentry trade in Basel - by being involved in practically all production processes, including material procurement and sales, and widows were often even allowed to run a craft business on their own. In line with economic needs, the development of certain technologies and the taste of the times, new professions such as book printer, copper engraver , organ builder and wig maker flourished in addition to the traditional trades such as butcher or goldsmith .

Handicraft history in Germany since the 19th century

Stimulated by the French Revolution and the ensuing industrialization , the freedom of trade slowly established itself in 19th century Europe , which granted every citizen the right to practice a craft of their own choice.

Freedom of trade was introduced in Prussia on November 2, 1810, and later, on June 21, 1869, freedom of trade was further expanded by means of a Reich law. Every citizen was now entitled to found a craft business. In 1897 and 1908 the trade regulations were finally amended; today it is generally regarded as the foundation of the dual system of vocational training .

Efforts on the part of the master craftsmen to restrict the freedom of trade again were evident. In 1897, for example, a Crafts Act was passed that legitimized a Chamber of Crafts and which all craftsmen had to join. In 1908 the “ small certificate of proficiency ” was issued, which again made the master craftsman's certificate necessary for the training of apprentices. The conclusion of the movement was the craft regulations of 1935 with the reintroduction of the large certificate of proficiency with which the master craftsman's certificate was required again even for the practice of a craft.

After the Second World War, an almost unlimited freedom of trade was introduced in the American zone of occupation - now based on the US model. The mandatory membership in the chambers and guilds (so-called institute of the facultative compulsory guild) now became a voluntary matter. From January 10, 1949, a postcard was sufficient to register a trade - there was no need for a master craftsman . A start-up boom set in again. In Munich alone, as many new businesses were registered in the first year of freedom as there were before.

However, this freedom was restricted again in 1953 with the adoption of the Crafts Code. For 94 skilled trades, the master craftsman's obligation was again introduced nationwide . The members of the Bundestag Richard Stücklen (CSU) and Hans Dirscherl (FDP) were in charge .

This necessity of the master craftsman's certificate was justified, among other things, with a particular susceptibility to danger and high demands on consumer protection as well as the necessary professional training. Manual self-employment without a master craftsman's certificate was therefore prosecuted as illegal undeclared work .

In 2003/2004 the Bundestag decided to amend this regulation: In the amendment to the trade law , freedom of trade was reintroduced in 53 trades (listed in Appendix B of the Crafts Code). The small certificate of competence is now sufficient for these professions. The remaining 41 trades (included in Appendix A of the Crafts Code) retain the requirement to submit a major certificate of proficiency, but alternatives to the master craftsman's certificate are to be created.

Characteristics of the craft as a special economic area

The craft is a heterogeneous (so versatile) economic area . The variants range from industrial suppliers to craftsmen in the consumer -related environment, from medium-sized companies with hundreds of employees to small businesses. Due to their size and range of services, craft companies are largely local or regionally oriented on both the sales and labor markets . Many areas of the craft industry are in direct competition with industrial production and undeclared work . The latter now accounts for over 15% of the gross domestic product in Germany, with an upward trend.

Germany

Fields of activity

According to the Crafts Code, the craft businesses are active in 41 trades requiring a license, 53 without a license and 57 similar trades. Crafts are defined by the areas identified in the craft regulations (positive list). As a result, skilled trades are predominantly restricted to markets whose expansion opportunities in the knowledge-based economy are sometimes considered to be limited. 43.4% of the companies from Appendix A are in the metal / electrical sector, 25.8% in the construction and finishing trades, 15.6% in the health, personal care or cleaning trades, 7.2% in the wood sector , 6.7% in the food industries, 1% in the glass, paper, ceramic and other trades and less than 1% in the clothing, textile and leather industries.

A separate topic or field of activity is the widespread handicraft botch, which means, on the one hand, illegal work or the work of people without a professional basis (who botch the legally active into the trade), and on the other hand, any inadequate execution of a craft, including botch called. According to the warranty obligation, a repair or some other compensation is then due. The dispute over this is increasingly preoccupying the courts, so that separate quality offices have been set up to regulate so-called minor cases; see also craftsmanship .

Companies and employees

Almost 5 million people work in around 887,000 companies, and almost 500,000 trainees are trained in the trade. This means that 12.8% of all employed persons and around 31% of all trainees in Germany are currently still active in the craft. Craft businesses are predominantly small businesses. A trade-related evaluation by the IAB Company Panel 2003 shows that 50% of the companies have fewer than five employees and 94% fewer than 20 employees. In 2003 around 20% of the craftsmen worked in companies with fewer than five employees, 35% in companies with more than 20 employees. The largest group of craftsmen (45%) thus worked in companies with five to 20 employees. The average company size in 2003 in the skilled trades with 7.6 employees was only half as large as in the economy as a whole. In 2009, sales in the craft sector reached around 488 billion euros. Since the amendment to the Crafts Code in 2004, the master craftsman's certificate as a prerequisite for the establishment of a trade was no longer required, the number of craft businesses has increased significantly, from 846,588 in 2003 to 975,000 in 2009.

The economic importance of the craft is not only evident from the number of businesses, the labor force employed there and their added value. In addition, the craft has a special regional political significance: The craft businesses are spread over the area and also bring growth and employment to the rural region. In structurally weak regions in particular, the availability of handicraft services is an important location factor: the local availability of handicraft services (suppliers, service providers, maintenance) is not infrequently an important factor when companies make location decisions. For private households, the local supply of handicraft services (e.g. groceries, car workshops, etc.) is a factor that conveys the quality of life and the attractiveness of the region.

Personnel structure and development

The personal qualification of the employees is the decisive success factor for the innovation and competitiveness of the craft.

- The share of skilled workers in the skilled trades was almost 40% in 2003. Unskilled workers made up only 18%. White-collar workers were represented less frequently in the skilled trades with 17% in the personnel structure compared to the economy as a whole (35%).

- The share of women in 2003 was just under 33%, well below the overall economic average of 43.3%.

- In 2003, around 25% of those employed in the skilled trades were employed in non-standardized employment relationships (e.g. part-time employment ).

- Employees from small businesses take part in external further training measures to a disproportionately low degree (70.6% of large businesses use offers from private training providers, but only 16.2% of small businesses).

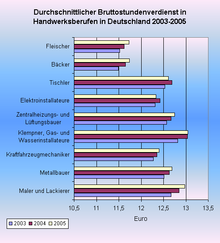

- The wages in handicrafts are around 25% lower than in industry. The gap between craft and industry is almost 1,000 euros per month for skilled workers or journeymen.

Company formation

The start-up rate in the craft trade was around 4.7% in 2001 (compared to around 12% in the economy as a whole). However, German craft companies have an above-average life expectancy. This is mainly due to the good preparation of the "start-up" young entrepreneurs because of the master craftsman's certificate ( large certificate of competence ) and the extensive start-up advice from the chambers of crafts.

Perspectives

The following development trends are decisive for the future of craft businesses in Germany - and Europe:

- The demographic development will change many sales markets for handicrafts; here there are both risks (loss of customers) and opportunities (offering special services for older customers). At the same time, it is becoming increasingly difficult for the skilled crafts sector to compete for qualified workers to recruit personnel to the extent and with the necessary qualifications.

- The innovative ability of the handicraft is significantly less pronounced than that of the industry. In contrast to industrial innovations, manual innovations relate in particular to company and application-related new developments, solutions and processes.

- International competition will also increasingly affect the craft; here, too, there are both risks and opportunities.

Against the background of these trends - which affect the various trades to different degrees - vocational training and further education is becoming more important than ever. The skilled trades can only master the challenges of the future and take advantage of future opportunities with well-trained staff. An attractive training and further education offer is also necessary in order to attract qualified young professionals to the craft.

Studies on the future of the craft have analyzed the opportunities and risks of this special economic sector with the following results.

- As an SME, many craft businesses can act very flexibly and dynamically in competition.

- However, they are often disproportionately affected by insufficient financing options, a shortage of skilled workers , a lack of experience and resources in the field of foreign trade and cooperation, as well as a lack of participation in research and development.

- In the skilled trades, traditionally low qualification expectations and the required high competence profile of employees to cope with complex tasks are falling further and further apart.

- The craft offers excellent identification options. Handicraft stands for regionality, origin, authenticity, handwork, transparency of materials, content and processing methods. Craft businesses tend to focus less on growth than on quality and balance.

- Handwerk in Germany makes innovative contributions to product developments. A study by Prognos AG examines the contribution made by the craft to innovation.

- Craftsmen deliver sophisticated and individual solutions in close customer contact and taking customer requirements into account.

- Craftsmen repair, replace and restore. When it comes to ecological and economic necessity, they are increasingly relying on the preservation of the existing.

- The craft is changing: companies that offer innovative, creative and complex services are experiencing an upswing, whereas traditional companies are increasingly expecting an economic downturn.

- Because of the skyrocketing raw material and energy prices, recycling , energy efficiency, minimized use of materials and repairs are gaining in importance as business areas in the trade.

- The 35 plus generation calls for future-oriented craftsmanship. Women in particular, who make up 80% of the decisions on the distribution of household income, should be the main target group.

- (Older) customers are not satisfied with high quality craftsmanship alone; Due to a change in values, they expect more fun and entertainment through products and services.

- Successful structuring of business partnerships for small and medium-sized businesses is becoming a question of survival, also in view of the many mistakes made. Cooperativity promises to increase the desired productivity disproportionately.

- Handicrafts from Germany have an excellent international reputation. Craft companies are increasingly finding markets in neighboring European countries, such as Great Britain, Poland, the Netherlands and Norway, after structural deficits there have led to a deficit of comparable craft skills.

- The trades are traditionally interested in vocational training. This is why the trade is also interested in ensuring that only well-trained craftsmen (ideally masters) are allowed to run a craft business. However, when the craft regulations were amended, trades without a master craftsman's qualification were also allowed to set up a craft business. The craft has an interest in carrying out a thorough, usually three-year training in a profession.

- There is currently a heated discussion about the classification of (manual) professions in a German qualifications framework . Ultimately, it is about the assignment of (manual) professions to school-leaving qualifications and about permeability and equal opportunities for access to universities, also for people with vocational training and a master's degree.

In all federal states, master craftsmen qualify at the same time with the master craftsman's examination or the examination to become a designer in the craft for authorization to study a subject of their choice at a university. In Bavaria, master craftsmen have had a university entrance qualification since the winter semester 2009/2010; 387 master craftsmen enrolled at the Bavarian universities in the winter semester 2009/2010. Journeyman craftsmen acquire the technical college entrance qualification.

In addition, there is an opportunity for further training for craftsmen to become "designers in the craft", where, among other things, courses in drawing and representation techniques, basics of design, color design, drafting, design, project development, materials science, work technology and model making, typography and layout, photography and documentation, Art and design history, presentation and design management must be documented. The examination takes place in the form of an extensive project work. The academies for design in Germany are affiliated to the educational offer of their respective chambers of crafts and offer the one-year full-time course or the part-time 2-year course. Various funding models support craftsmen in this.

organization structure

The craft is organized in Germany as follows:

Every craft business that is subject to authorization, the non-authorization and craft-like trades are compulsory members of the regionally competent Chamber of Crafts (comparable to the Chamber of Industry and Commerce or the Chamber of Lawyers ). The chambers form regional chamber days at the level of the federal states and the German Chamber of Handicrafts as the central organization of the chambers of craft in Germany.

Furthermore, many craft businesses are voluntarily organized in guilds . This Innungen of a circle forming at regional level circuit artisan properties . Guilds of the same or technically related trades of one or more federal states can join together to form state specialist or state guild associations. These associations can come together at state level to form regional cross-trade regional associations as state-wide employers 'associations (often referred to as employers' associations or general associations). At the federal level, they form the federal guild associations or central specialist associations, which have come together in the Entrepreneurs' Association of German Crafts (UDH) as the central organization of employers in the craft sector in Germany.

In the federal states, the regional chamber days with the employers' and general associations form the regional craft days as the representation of the craft at the state level.

The 53 chambers of handicrafts and 36 central trade associations form the Central Association of German Handicrafts (ZDH) with other important craft institutions .

The ZDH is a member of UEAPME , the European Union of Crafts and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises based in Brussels.

Other craft organizations are z. B. the juniors of the craft, who specifically represent the interests of young master craftsmen and executives, as well as the working group entrepreneur women in the craft as a representation of the entrepreneurs working in the craft and women working in management positions in the craft.

The following graphic gives an overview of the German craft organization:

Quotes

Richard Sennett : “Doing something right even when you don't get anything for it, that's true craftsmanship. And I believe that only such a disinterested sense of commitment and obligation can elevate people emotionally. Otherwise they are defeated in the struggle for survival. "

“A broad definition [for a craft attitude (in the broader sense)] could be: doing something well for its own sake. Discipline and self-criticism play an important role in all areas of craftsmanship. You orient yourself to certain standards, and ideally the pursuit of quality becomes an end in itself. "

See also

- Craftsman honor

- Master craftsman

- The last of his class? (a documentary TV series by the BR about rare crafts)

- Handicrafts (applied arts )

- Central Association of German Electrical and Information Technology Trades

- Artigiano in Fiera

literature

- Jürgen Dispan: Regional structures and employment prospects in the craft. Regional analysis, development trends, challenges, regional policy fields of action, implementation approaches in the Stuttgart region . IMU Institute, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-934859-05-4 (series of publications Verband Region Stuttgart, issue 20).

- Rainer S. Elkar with the collaboration of Katrin Keller and Helmuth Schneider : Crafts - From the beginning to the present. Theiss Verlag, Darmstadt 2014. 224 pages. ISBN 978-3-8062-2783-3 .

- Wolfgang Herzog: WissensQuick: Future apprenticeship in the craft. Why an apprenticeship in the craft has the best future prospects. A plea from an experienced master craftsman. Edition Aumann, Coburg 2011. 87 pages. ISBN 978-3-942230-75-9 .

- Peter John: Handicrafts in the field of tension between the guild order and freedom of trade - development and policy of the self-governing organizations of the German handicrafts until 1933 Bund-Verlag Cologne 1987.

- Arnd Kluge: The guilds . Steiner, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-515-09093-3 .

- Thomas Schindler, Carsten Sobik, Sonja Windmüller (eds.): Craft. Anthropological, historical, folkloric (= Hessische Blätter für Volks- und Kulturforschuing NF 51). Jonas, Marburg 2017. ISBN 978-3-89445-543-9

- Knut Schulz (Ed.): Craft in Europe. From the late Middle Ages to the early modern period (= writings of the Historisches Kolleg . Colloquia 41). Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 978-3-486-56395-5 ( full text as PDF )

- Knut Schulz : Crafts, guilds and trades. Middle Ages and Renaissance . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-20590-5 .

-

Richard Sennett : Handwerk Berlin-Verlag, Berlin 2008 ISBN 3-8270-0033-5 (sociological, see e.g. quotations)

- Review: Thomas Macho in NZZ, January 24, 2008

- Jendrik Scholz: The Crisis of the Corporatist Arrangement and Trade Union Revitalization Approaches in Crafts , in: Schmalz, Stefan; Dörre, Klaus (Ed.): Comeback of the trade unions? New power resources, innovative practices, international perspectives, Frankfurt am Main 2013, pp. 199–212, Campus-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-593-39891-4

- Jendrik Scholz: Regional structural policy using the example of Trier and Luxembourg - development of methods, instruments, reference processes and political recommendations for action to promote technology and innovation transfer in the craft sector , in: Verwaltung & Management - Zeitschrift für Allgemeine Verwaltung, Volume 15, Issue 3/2009, Pp. 163-167

Web links

- Central Association of German Crafts V.

- Federal Statistical Office (Destatis): data and articles on the subject of "craft"

- Anne-Marie Dubler: Craft. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andreas Hüttner: Technology didactics . In: Martin Rothgangel, Ulf Abraham, Horst Bayrhuber, Volker Frederking, Werner Jank, Helmut Johannes Vol (eds.): Learning in the subject and beyond the subject: Inventories and research perspectives from 17 subject didactics in comparison (= subject didactic research ). 1st edition. tape 12 . Waxmann, Münster 2019, ISBN 978-3-8309-9122-9 , pp. 419 f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 9, 2020]).

- ^ Fritz Westphal: The writing and the historical craft . In: Die deutsche Schrift (Hrsg.): Bund für deutsche Schrift und Sprach e. V. No. 3/2016 . Bund für deutsche Schrift, 2016, ISSN 0012-0693 , Handwerk has golden ground, p. 11 , col. left .

- ↑ Johan Agricola: Sibenhundert and funffzig German proverbs ... Wittenberg in 1582; Reprint of Luther sites and museums in Lutherstadt Eisleben: We must save the proverbs ... Halle and Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-929330-55-5 .

- ^ Stefan Hess , Wolfgang Loescher : Furniture in Basel. Art and craft of the carpenters until 1798. Basel 2012, ISBN 978-3-85616-545-1 .

- ↑ Scholz, Jendrik: Crisis of the corporatist arrangement and union revitalization approaches in the handicraft , in: Schmalz, Stefan; Dörre, Klaus (Ed.): Comeback of the trade unions? New power resources, innovative practices, international perspectives, Frankfurt am Main 2013, pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Scholz, Jendrik: Regional structural policy using the example of Trier and Luxembourg - development of methods, instruments, reference processes and political recommendations for action to promote technology and innovation transfer in the craft sector , in: Verwaltung & Management - Zeitschrift für Allgemeine Verwaltung, Volume 15, Issue 3 / 2009, pp. 163-167.

- ^ Sennett, Richard: The culture of the new capitalism. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2005, p. 155.

- ^ Sennett, Richard: The culture of the new capitalism. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2005, p. 84.

- ↑ Scholz, Jendrik: “Crisis of the corporatist arrangement and trade union revitalization approaches in the craft” on nbn-resolving.de .

- ↑ [1] .