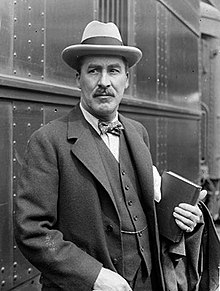

Howard Carter

Howard Carter (born May 9, 1874 in Kensington , † March 2, 1939 in London ) was a British Egyptologist . Howard Carter became known in 1922 through the discovery of the almost untouched tomb of Tutankhamun ( KV62 ) in the Valley of the Kings in West Thebes .

Life

Origin and education

Howard Carter was born in Brompton, Kensington , London in 1874 , the youngest of 11 children of animal painter and illustrator for the Illustrated London News, Samuel John Carter and his wife Martha Joyce (Sands) Carter . He grew up in Swaffham . For health reasons, Carter was homeschooled and learned drawing from his father. His talent in drawing enabled him to enter archeology through Percy E. Newberry .

The early years in Egypt

Carter initially worked for three months in the British Museum through Newberry before starting his work as a draftsman and painter for the Egypt Exploration Fund (later: Egypt Exploration Society ) at the age of 17 with the support of Lady Amherst . Under the direction of Percy E. Newberry, he drew some pictures from the tombs of Beni Hassan . For the famous Egyptologist Flinders Petrie he worked in Amarna in 1892 and made numerous drawings. The collaboration with the "toughest and strictest of all teachers" lasted until May 1892. Carter first came into contact with the Amarna period through the artistic discoveries and Petrie took him with him in February 1892 to visit the royal tomb of Akhenaten, which was discovered in 1891 . The grave was very disappointing to Carter, as he wrote to Newberry. After more than four months, Howard Carter had gained his first experience as an excavator. Flinders Petrie went on to describe Carter as "a good-natured fellow whose interests are focused entirely on painting and natural history ... there is no point in training him to be an excavator."

From 1893 to 1899 he copied paintings, reliefs and inscriptions in the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari for Édouard Naville . During the time with Petrie and Naville he learned the basics of archeology and Egyptology and how to read the hieroglyphs .

With the support of the director of the Egyptian antiquities administration ( Service des Antiquités d'Egypte ), Gaston Maspero , Howard Carter was appointed chief inspector of the antiquities administration in Upper Egypt and Nubia in 1899 . In the same year he made the acquaintance of Theodore Davis . As chief inspector, Carter reorganized the administration of the service under Sir William Garstin and Maspero. In 1902 he began overseeing the excavations of Theodore Davis in the Valley of the Kings. During this time, the graves of Thutmose IV ( KV43 ) and that of Hatshepsut ( KV20 ) were uncovered . Carter had repair and restoration work in the graves of Amenhotep II ( KV35 ), Ramses I ( KV16 ), Ramses III. ( KV11 ), Ramses VI. ( KV19 ) and Ramses IX. ( KV6 ) in the Valley of the Kings and equip both these graves and the grave of Seti I ( KV17 ) with electric light in 1903.

His contract for Upper Egypt ended in 1904 and he was transferred to Lower Egypt as Chief Inspector . A year later there was an incident in Saqqara with drunken French tourists who asked Petrie to take a tour of the mastaba and who penetrated the quarters of the students and Petrie's wife. After fights with an Egyptian guard, the French reported the incident to Maspero. Carter had given the Egyptians express permission to fight back. Since he then refused to apologize to the French consul general, Carter was dismissed by Maspero. Then Carter worked as an artist ( watercolor painter ), antique dealer, tourist guide and interpreter in Luxor until 1908 . Among other things, he drew objects from the only partially robbed grave of Juja and Tuja ( KV46 ), which was found in 1905 by James Edward Quibell .

In 1907 he began working with Lord Carnarvon , whom Howard Carter had met through Gaston Maspero. Carter carried out excavations for Carnarvon in Thebes and some sites in the Nile Delta . At Dra Abu el-Naga they discovered tombs from the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period , which they also published. In Thebes they led further excavations at the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari and at a temple of Ramses IV. In the delta, work followed at Sakha and Tell el-Balamun . During this time Carter discovered the graves of Amenhotep I (grave AN B in Dra Abu el-Naga), an unused grave of Queen Hatshepsut, and carried out work on the tomb of Amenhotep III in 1915 . ( WV22 ). The work on WV22 remained unpublished. In 1910, with financial help from Lord Carnarvon, Carter had a new excavation house and a new house built for himself at Elwat el-Diban on the north end of Dra Abu el-Naga. In 1912 he acquired antiquities on the antique market for Lord Carnarvon's private collection.

In 1914, Theodore M. Davis gave back his excavation license for the Valley of the Kings for health reasons, which Lord Carnarvon received in June of the same year, but was not signed until April 18, 1915 by Georges Daressy and Howard Carter. With the outbreak of World War I , work in the Valley of the Kings could not start as planned. Lord Carnarvon returned to England and Howard Carter worked as an interpreter for the British military during this time. In December 1917 a series of short excavations followed in the Valley of the Kings, the results of which were disappointing for Carter. In contrast to Theodore M. Davis, however, he was firmly of the opinion that the Valley of the Kings was by no means exhausted and the tomb of Tutankhamun could still be found. In the 1917/18 excavation season he sponsored a series of "checklists" for the burial of Ramses VI. and a depot with calcite vessels that had held oil for the embalming of Merenptah come to light. Because of the poor results, but very high costs for the work in the Valley of the Kings, Lord Carnarvon threatened to end the financing and thus the excavations. During a last conversation at Highclere Castle , Howard Carter even offered to finance a full season of digging from his own resources. However, a possible find would be attributed to Carnarvon, who still held the excavation license. Lord Carnarvon agreed to another and at the same time final excavation season and its financing.

Discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb

1 treasure chamber, 2 burial chamber with sarcophagus ,

4 antechamber, 5 side chamber,

8 corridor, 10 stairs

Howard Carter arrived in Egypt on October 27th, and the work of this final excavation season began on November 1st, 1922. On November 4th, 1922, the workers in the Valley of the Kings found the excavation area at the tomb of Ramses VI. on a stone step. The stairs, filled with rubble, were exposed, and undamaged seal impressions of the necropolis were visible at the top of the walled-up doorway : in a cartouche the god Anubis in the form of a jackal lying over nine prisoners, the so-called nine arches . Howard Carter then telegraphed Lord Carnarvon:

" At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley a magnificent tomb with seals intact recovered same for your arrival congratulations.

I finally made a wonderful discovery in the valley. Magnificent grave with intact seals. Covered up again until you arrive. Congratulations. "

Howard Carter found the seals or cartouches for assigning the grave only after the steps had been completely exposed. As the 62nd grave discovered in the Valley of the Kings, it was named KV62 . In early 1923, Flinders Petrie commented on the discovery of the Royal Tomb: "We are lucky that all of this is in the hands of Carter and Lucas." According to TGH James , this was the greatest praise Carter could ever have received. This unique find presented the discoverer with a great logistical challenge: Electric power, materials and personnel were required for the general work, the recovery, cataloging of objects found in the grave as well as conservation work and transport to Cairo. Carter's excavation team included himself and Lord Carnarvon: Arthur C. Mace, Alfred Lucas, Harry Burton , Arthur Callender, Percy E. Newberry , Alan Henderson Gardiner , James Henry Breasted , Walter Hauser, Lindsley Foote Hall and Richard Adamson.

Until the arrival of Lord Carnarvon on November 23, 1922, the stairway was filled with rubble again. When it was exposed again after Carnarvon's arrival, the royal seal of the tomb owner was found: Tutankhamun. Carter found that the tomb had already been opened and resealed at least twice in ancient times. Behind the wall was a corridor filled with rubble, which was uncovered by November 26th. The excavation team came across another walled-up door entrance with seals, behind which the so-called “antechamber” ( Antechamber ) was located. The official opening of the tomb was on November 29th, and the official opening of the burial chamber followed on February 16, 1923.

On April 5, 1923, Lord Carnarvon died and the excavation license passed to his wife, Lady Almina Carnarvon, who continued to give Carter full support. On her behalf, Carter applied for an extension of the excavation concession, which was granted by James E. Quibell, the then General Inspector of Antiquities.

In February 1924, Carter and the Egyptian government came to a dispute. After the sarcophagus was opened , the government objected to the presence of the archaeologists' wives in the tomb. Carter did not accept this decision and responded with a strike by his workers and the closure of the tomb. The sarcophagus lid still floated on ropes over the sarcophagus at this time. As a result of Carter's reaction, Lady Carnarvon was withdrawn from her excavation license on February 20. His behavior, often referred to as a "quick temper," and the incident led to a change in the concession: The license was only granted for a year and provided that Howard Carter performed the function of an unauthorized overseer and received five Egyptian assistants. Only the government was allowed to issue permits to visit the grave, and Lady Carnarvon had to report every fortnight about her visits to the grave. She also had to have a list made of all the objects found in the grave and was obliged to publish a publication within five years of the final work on the grave. The original division into equal halves was obsolete and all items found in the tomb were the property of the Egyptian government. It was not until 1930 that the Lord Carnarvons family received compensation for the excavation cost of £ 35,971 . Howard Carter himself had been promised a quarter of the sum by Lady Carnarvon. He received the amount of £ 8,012.

Carter worked very meticulously and carefully noted the contents of the grave in his records and index cards. His diary entries contain more or less detailed information on all excavation campaigns. The work in KV62 took a full nine excavation seasons and should take a total of 10 years. They were not fully completed until 1932. Tutankhamun's grave contained a total of 5398 objects, of which the most famous find is probably the "golden death mask of Tutankhamun". Most of the finds from KV62 are now on display or in the magazines of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . The sarcophagus, the outer of the three coffins and Tutankhamun's mummy have remained in the Valley of the Kings.

Howard Carter gained worldwide attention through the discovery of the almost pristine grave. In contrast to Lord Carnarvon, however, it was much more difficult for him to deal with the sudden fame. The “find of the century” not only attracted masses of visitors and the press in the Valley of the Kings, but also increased the already general interest in ancient Egypt to the point of “ Egyptomania ”. The archaeological work on the grave was increasingly hindered by numerous visitors and journalists, which Howard Carter repeatedly complained in his excavation diary for years. In 1923 Lord Carnarvon finally signed an exclusive contract with the London Times , which secured the newspaper the first coverage of all events connected with the find. Only after it was published in the Times were other newspapers, including the Egyptian one, allowed to report. Worldwide coverage of the work on Tutankhamun's tomb was the first media hype of its time. Since Carnarvon used to deal with the press and Howard Carter was able to devote himself so fully to the work in the grave, after the death of the Lord he was increasingly overwhelmed with the journalists on site and the coverage of the excavation.

The death of Lord Carnarvons increased the media hype about the grave even more: The newspapers now reported on the curse of the Pharaoh (also "curse of Tutankhamun") and supported themselves. a. on statements by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the occultist Marie Corelli .

Howard Carter brought out the three-volume publication The tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen (1923-1933) together with Arthur C. Mace . A full evaluation of his records and the index cards is still pending. For example, so far only 30 percent of the objects found in the grave have been scientifically examined.

As the discoverer of the tomb Carter received the honorary doctorate of the Yale University .

Criticism of Carter's work on the grave

The representations and descriptions of Howard Carter about the finding of the grave and the work in the grave are repeatedly questioned by various Egyptologists. For example by Thomas Hoving , the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York , in 1978: Carter entered the grave without permission and removed small objects from it that had not been registered and are now in various museums. Hoving relies on various documents and memos that he used for researching his book The Golden Pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun found in the museum archives.

The most famous object that Howard Carter is said to have “suppressed” is the “ head on the lotus blossom ” painted from wood . This was not noted in the records and not registered. He was after the strike and the change of license at the end of March 1924 by Pierre Lacau and Rex Engelbach during an inventory of the KV4 , the grave of Ramses XI. , relocated grave goods found in a red wine box between supplies. At that time Carter was in London preparing his lecture series in the United States. According to him, the "head of Nefertem" was found in the corridor of KV62.

The discovery of the grave just three days after the start of the excavation season is also regarded as a strange coincidence. The Egyptologist Christine El Mahdy pointed out that Carter must have known the location of the tomb before it was discovered, since the protective wall that was erected to the tomb of Ramses VI. ( KV9 ) was erected before the tomb of Tutankhamun was found and closes exactly without obstructing the entrance of KV62.

In January 2010, the news magazine Der Spiegel reported again about doubts about Carter's descriptions and largely relied on statements by Thomas Hoving from the 1970s and, more recently, on the Egyptologists Christian Loeben and Rolf Krauss . Loeben sees a shabti of Tutankhamun in the Louvre, for example , who bears the throne name of the king and has been known to him since 1982, as questionable. Krauss, on the other hand, after looking at old photos from the grave with footprints and a note from Rosemarie Drenkhahn, came to the conclusion that it was possibly Carter's own prints and not the ancient grave robbers.

Jaromir Malek , former head of the University of Oxford associated Griffith Institute in Oxford , documentation kept in the Carter, held not only premature discovery of the tomb illogical, but also sees the meticulousness, worked with Carter, as opposed to those put forward Allegations. He would not call Howard Carter a “thief” because he would never have tried to sell items from the grave.

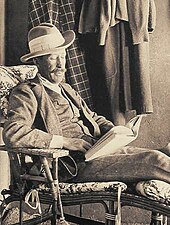

After Tutankhamun's tomb had been finally cleared and cleaned in 1932, Carter published the third and final volume of The tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen in 1933 . A six-volume publication entitled A Report upon the Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen was planned for the next few years . Work on this was slow and never finished. Before he returned to England, he lived in seclusion in his home in West Thebes , near the Valley of the Kings. Carter often stayed in the foyer of the Winter Palace in Luxor , but hardly spoke a word to anyone and isolated himself from society. Occasionally he led dignitaries or personalities through the Valley of the Kings, the place of his "archaeological triumph". King Faruq took part in the last documented tour in 1936 . At the end of this, Howard Carter mentioned the tomb of Alexander the Great ("Alexander Tomb "), which researchers had been looking for for a long time, and stated that they knew where it could be found. But he also added: I shall not tell anyone about it, least of all the Antiquities Department. The secret will die with me. ("I won't tell anyone about it, especially not the antiquities administration. This secret will die with me.") After this encounter, Prince Adel Sabit described Howard Carter as "[...] a strong, vital personality, a little grumpy, grumpy to the people." People with an aversion to tourists, who was nevertheless a charming and interesting man as long as he did not utter thundering curses against the Egyptian antiquities administration with which he had long been feuding [...] "

Death and inheritance

Howard Carter died on March 2, 1939 in Kensington at his home at 48 Albert Court at the age of 64. His death certificate lists two causes of death: cardiac failure and lymphadenoma ( malignant lymphoma ). He died of heart failure due to Hodgkin lymphoma . His niece Phyllis Walker, who had been his secretary and trusted companion for years, had been with him for the last few hours. He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in London on March 6th . In contrast to the extensive coverage of the tomb discovery and the ongoing work on Tutankhamun's tomb, the Times , which at the time had concluded an exclusive contract with Lord Carnarvon, only mentioned Howard Carter's death in a list of numerous obituaries. Among the few mourners were Lord Carnarvon's daughter, Lady Evelyn Beauchamp, his niece Phyllis Walker, his brother William and nephew Samuel John, and a few friends of the family. There were numerous mourning vessels from London society, but none from an archaeologist or an Egyptologist.

The inscription on the old tombstone originally read:

- Egyptologist, discoverer of the tomb of Tutankhamun, 1922

- (Egyptologist, discoverer of the tomb of Tutankhamun, 1922).

After the tombstone and surround were renewed, the following inscription from the lotus chalice , called the Wishing Cup by Carter , from Tutankhamun's tomb was added on the stone:

- May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you, who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness.

- "May your Ka live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, you sit with your face in the north wind, your eyes behold bliss."

Carter bequeathed his personal property to his niece Phyllis Walker in a will drawn up in 1931. He left his house with contents in Egypt to the Metropolitan Museum. Since 2009, Carter's house has been restored and opened to visitors as a museum. His servant Abd el-Aal Ahmed Sayed, who had been in Carter's service for 42 years, received 150 Egyptian pounds . Howard Carter's books and furniture were auctioned off at Sotheby’s auction house. Some of Carter's antique collection went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo or was sold. Most of the records relating to his work on grave KV62, such as index cards, notes and drawings, are now held in the Griffith Institute at Oxford University , including the photos of Harry Burton , which were given to the Institute by his niece Phyllis Walker in 1946. Today 95% of the documents can be viewed online. Carter's excavation diary is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

In July 1931 Carter had appointed photographer Harry Burton of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Bruce Ingram, editor of the Illustrated London News , as his executors. Both received £ 250 from him. His personal property went to Phyllis Walker with the instruction:

... and I strongly recommend to her that she consult my Executors as to the advisability of selling any Egyptian or other antiquities included in this bequest.

"... I strongly recommend that she seek the advice of my executors as to the advisability of selling any Egyptian or other antiques that include this legacy."

Among the antiques were a small number of pieces that no doubt came from Tutankhamun's tomb. They took the advice of Percy Newberry , separated the pieces from the rest of the heritage, and decided with Phyllis Walker that these should be returned to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Meanwhile the Second World War had broken out. Rex Engelbach from the Cairo Museum was not very accommodating. At first they hoped the items could be sent by diplomatic mail, but the State Department took a stand. Burton was able to persuade Sir Miles Lampson , the British ambassador to Egypt, to help if the jewelry could be imported as normal. Unfortunately, Burton died in 1940.

On March 22, 1940, Phyllis Walker wrote to Étienne Drioton , then general director of the Antiquities Service, and offered him the pieces. Drioton had been informed by Burton. He replied very kindly and thanked her for her generosity and there would be no press campaign either. He spoke to King Faruq , who spontaneously agreed to act as an intermediary in the delivery to the Egyptian Museum. Finally, he suggested that the pieces should be sealed and delivered to the Egyptian consulate in London, who should be instructed to hand them over to the king. Finally, on October 12, 1946, Phyllis Walker was able to inform Percy Newberry that the "objects" had been returned to Egypt by plane. King Faruq then gave them to the museum in Cairo.

Alan Gardiner remarked on this to Newberry on March 21, 1945: Oh yes, of course, I knew everything about the handing over of the objects from the tomb to the Egyptian Embassy. I had counseled this all along to Carter himself. ("Yes, of course, I knew all about the delivery of the pieces from the tomb to the Egyptian embassy. I had recommended this to Carter myself all along.")

This suggests that Carter must have shown the objects to Gardiner before and must have expressed his concern about the property. It is not known whether they come from Carnarvon's collection or from Carter himself. Because he did not have a good relationship with Rex Engelbach from the Cairo Museum to carry out the delicate matter without public, Carter had left this to his executors.

Fonts

- The tomb of Thoutmôsis IV. Westminster 1904.

- with Theodore M. Davis, Edouard Naville: The tomb of Hâtshopsîtû. 1906.

- with George Carnarvon: Five years' explorations at Thebes. London 1912.

- Tut-ankh-amen. The Politics of Discovery. 1923-1924.

- with Arthur C. Mace: The tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen. 3 volumes. London 1923-1933.

- with Arthur C. Mace: Tut-ench-Amun, an Egyptian royal tomb, discovered by Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter. 3 volumes, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1924–1934.

literature

- Arnold C. Brackman : They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0333-9 .

- Aidan Dodson : Carter, Howard. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 190-191.

- Zahi Hawass : King Tutankhamun. The Treasures of the Tomb. Thames & Hudson, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-500-05151-1 .

- Wolfgang Helck , Eberhard Otto : Small Lexicon of Egyptology. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04027-0 , p. 59.

- Thomas Hoving: The Golden Pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun. Gondrom, Bayreuth 1984, ISBN 3-8112-0398-3 .

- TGH James : Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. IB Tauris, London 1992; Revised new edition: Tauris Parke, London 2006, ISBN 1-84511-258-X .

- TGH James: Tutankhamun. Müller, Cologne 2000, ISBN 88-8095-545-4 , pp. 44-73.

- Nicholas Reeves : The Complete Tutankhamun. Thames & Hudson, London 1995, ISBN 0-500-27810-5 .

- Nicholas Reeves, John H. Taylor: Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. British Museum Press, London 1992, ISBN 0-7141-0959-2 .

- Nicholas Reeves: Fascination Egypt. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-89405-430-1 , p. 160.

- HVF Winstone: Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tut-Ench-Amun. vgs, Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-8025-2228-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Howard Carter in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Howard Carter in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Film / Video Tut-Anch-Amun - the golden Pharaoh , history portrait, Great Britain 1998, 45 minutes, screenplay: Christopher Rowley, Phoenix (German)

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation at Griffith Institute

- Howard Carter (1874–1939) at Theban Mapping Project

- Archeology: Raid into the Holy of Holies in Der Spiegel , issue 2/2010

- Works by Howard Carter in the Gutenberg-DE project

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b N. Reeves: Fascination Egypt. Munich 2001, p. 160.

- ↑ T. Hoving: The golden pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun. Bayreuth 1984, p. 19.

- ↑ N. Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun. London 1995, p. 40.

- ↑ TGH James: Tutankhamun. Cologne 2000, p. 48.

- ↑ TGH James: Tutankhamun. Cologne 2000, p. 46.

- ↑ T. Hoving: The golden pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun. Bayreuth 1984, p. 20.

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson: The Valley of the Kings. Mysterious realm of the dead of the pharaohs. Econ, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-430-17664-6 , p. 72.

- ↑ T. Hoving: The golden pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun. Bayreuth 1984, p. 21; TGH James: Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 114.

- ↑ N. Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun. London 1995, p. 41.

- ^ G. Carnarvon, H. Carter: Five years' explorations at Thebes. London 1912.

- ^ N. Reeves, RH Wilkinson: The Valley of the Kings. Mysterious realm of the dead of the pharaohs. Düsseldorf 1997, p. 111.

- ^ TGH James : Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. Revised new edition: London 2006, p. 477.

- ^ Highclere Castle: The Path to Discovery. On: highclerecastle.co.uk ; accessed on October 21, 2015.

- ↑ N. Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun. London 1995, p. 50.

- ↑ Howard Carter's diary with entries from November 5 and 6, 1922 On: griffith.ox.ac.uk ; accessed on October 21, 2015.

- ↑ TGH James: Tutankhamun. Cologne 2000, p. 46.

- ↑ N. Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun. London 1995, pp. 56-57.

- ↑ T. Hoving: The golden pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun. Bayreuth 1984, p. 325.

- ^ The Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. The Howard Carter Archives. Excavation journals and diaries made by Howard Carter and Arthur Mace: 8th Season, 1929–1930 , accessed December 14, 2015

- ^ TGH James : Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. IB Tauris, London 1992; Revised new edition: Tauris Parke, London 2006, ISBN 1-84511-258-X , p. 434.

- ↑ AC Brackman: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 125.

- ↑ a b Claudia Sewig: Expert rehabilitates Tutankhamun's discoverer. On: Abendblatt.de ( Hamburger Abendblatt ) of January 21, 2010, accessed on October 21, 2015.

- ↑ T. Hoving: The golden pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun. Bayreuth 1984, p. 327.

- ^ Z. Hawass: King Tutankhamun. The Treasures Of The Tomb. London 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Christine el Mahdy: Tutankhamun. Life and death of the young pharaoh. P. 84.

- ↑ a b Andreas Austilat: Archeology: Savior or Robber? On: tagesspiegel.de from January 22, 2010; accessed on October 21, 2015.

- ↑ N. Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun. London 1995, p. 67.

- ↑ N. Reeves, JH Taylor: Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London 1992, pp. 178-180.

- ↑ N. Reeves, JH Taylor: Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London 1992, pp. 179–180 .: […] Howard Carter is a forceful and vital personality, but grumpy and rather dour with people, tourists being his pet aversion. Carter can be nevertheless be a charming and interesting man when he is not thundering imprecations on the Egyptian government's Antiquities Department, with whom he had a long standing feud [...]

- ^ Archeology Archive: The Man Who Found Tut. On: archive.archaeology.org ; accessed on October 21, 2015.

- ^ TGH James: Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 468.

- ↑ N. Reeves, JH Taylor: Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 180.

- ^ TGH James: Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Fiona Carnarvon, 8th Countess of Carnarvon: Carnarvon & Carter. The Story of the Two Englishmen who Discovered the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Highclere Enterprises, 2007, p. 88.

- ^ TGH James: Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 468.

- ^ Find a grave: Howard Carter's grave in Putney Vale , accessed January 3, 2015

- ↑ N. Reeves, JH Taylor: Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 188.

- ↑ TGH James: Tutankhamun. Cologne 2000, p. 311.

- ↑ Nevine El-Aref in: Al-Ahram Weekly Online: News from Thebes ( Memento of 14 December 2011 at the Internet Archive .) Issue No. 973, November 19 to 25 in 2009.

- ↑ N. Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun. London 1995, p. 67.

- ↑ Marianne Eaton-Krauss: Tutankhamun - then and now. in: Wolfgang Wettengel (Ed.): Myth of Tutankhamun. Nördlingen 2000, ISBN 3-00-006214-9 , p. 93.

- ^ TGH James: Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. London 1992, p. 469 ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Carter, Howard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British Egyptologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 9, 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kensington (London) |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 2, 1939 |

| Place of death | London |