Curse of the pharaoh

The curse of the pharaoh describes the idea that the ancient Egyptian kings ( pharaohs ) protected their graves against intruders with magical spells. This curse is mostly associated with deaths that occurred in the years following the opening of Tutankhamun's tomb ( KV62 ) in the Valley of the Kings by Howard Carter in 1922. Another name is therefore the curse of Tutankhamun . Curses are also assigned to other graves in and outside Egypt when the peace of the deceased is disturbed.

The legend about the "curse of the pharaoh" has its origins in the 1820s. At this time a bizarre theater performance took place near London's Piccadilly Circus , in which mummies were unwrapped (see also mummy parties ). It is believed that this inspired the writer Jane C. Loudon to write her book The Mummy !: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century . Other stories about mummies, including one by Arthur Conan Doyle , followed and preceded the discovery of the tomb.

The story of the "curse of the Pharaoh" found a lot of media coverage at the time of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings and its creation in the contemporary reporting of the daily newspapers , which was also discussed differently in the following decades in literature and film. The effectiveness or existence of such a curse in connection with the opening of the young king's tomb or other graves has not been established. The belief in the "curse of Tutankhamun", which has persisted into our time, is based on superstition , rumors , misinterpretations and incomprehension of ancient Egyptian texts and is the interpretation of various events by journalists or book authors .

In contrast to the view as magic , the "curse of the Pharaoh" in the representations of the media, for years, apparently alternatively only refers to the apparent accumulation of deaths and attempts to explain them scientifically / medically, such as poisonous or radiant ones Substances or pathogens ( mold ) that may even have been used intentionally to protect the grave. Even with these meanings, the existence of the "curse" is doubted.

Finally, there is the jokingly modified meaning of the "Curse of the Pharaoh" as traveler's diarrhea (traveler's diarrhea), a really frequent bowel disease .

Tomb curses in ancient Egypt

Grave curses and death wishes are documented for ancient Egypt, but rare in all epochs. There are examples in graves that contain threats to gain respect for the dead. Scientists who have dealt extensively with grave curses point out, however, that the curses were mainly aimed specifically at employees of the necropolis . Every day they were tempted to acquire grave goods or to be bribed by grave robbers . Other grave curses should take effect if the cult of the dead or the memory of the deceased are neglected . Both earthly and otherworldly punishments are conjured up in them. Perhaps the oldest warning of the Old Kingdom comes from the 5th Dynasty , which says:

- "The great God will judge all those who make this tomb their own burial place or do evil to it."

In the 13th Dynasty a person named Teti apparently embezzled part of the grave goods and was severely punished by the priests for this:

- “Expel him from the temple, remove him from office, him and his son's son and the heirs of his heir. Let him be cast out on earth; his bread, his food, his consecrated flesh are taken from him. Nothing in this temple should remind of his name. His writings are wiped out in the temple of the fertility god Min , in the treasury and in every other book. "

The curses concerned both the “physical sphere” of a person, i.e. one's own physical existence, and the “social sphere”, in particular the name and the social environment , such as the family. Such inscriptions with curses were usually directed against potential grave robbers and aimed at the complete annihilation of a person: in the hereafter (the afterlife after death) as in this world (the memory of the deceased).

Discovery of the grave

Tutankhamun's tomb is one of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings , ancient Thebes on the west bank of the Nile. In the Egyptological nomenclature of the sites in the Valley of the Kings , Tutankhamun's tomb is referred to as KV62.

The archaeologist Howard Carter led the excavation on behalf of the British aristocrat Lord Carnarvon . For financial reasons, this would be the last Carnarvon sponsored dig and collaboration with Carter.

On November 4, 1922, Carter discovered the above-ground access to the grave: a staircase leading downwards and filled with rubble. A day later, at the end of the door, the upper part of a door with seal impressions of the city of the dead was exposed. Carter made a small opening and saw another corridor filled with rubble. Assuming that he was looking at the untouched grave of an important person or something similarly valuable, he telegraphed Lord Carnarvon, who was in England. He had the previously uncovered steps backfilled with rubble until Carnarvon's arrival. On November 7th, Howard Carter noted in his diary:

"[...] The news of the discovery spread almost all over the country, and inquisitive inquiries mingled with congratulations from this moment became the daily program. ("The news of the discovery spread all over the country, and from that moment intrusive questions mixed with congratulations became the daily program.") "

Lord Carnarvon arrived in Luxor on November 23rd, the following day his daughter, Lady Evelyn, who brought a bird. Carter's most important collaborator was Arthur R. Callender. In the presence of the general inspector of the antiquities administration at that time (today SCA ), Reginald Engelbach , and private persons he brought with him, the stairs were uncovered again on November 24th up to the sealed entrance.

Howard Carter (1924)

First exposures and public appointments

The sealed entrance was opened on November 25th, the adjoining corridor to another door with seals was exposed until the afternoon of the next day in the presence of Lord Carnarvon and his daughter. On November 27th, they entered the next room: the so-called “antechamber” (Antechamber) . A large number of objects, including two life-size guardian statues, pieces of furniture and vases, were found in a shambles that had to be cataloged and removed over the next few weeks. In the afternoon a representative of Engelbach joined them, who himself did not arrive until November 28th.

On November 29th an "official" opening of the grave took place in the presence of important personalities from the area, in the afternoon a report was sent to the London Times by messenger . Further visitors had to be turned away the following day because of the condition of the antechamber.

From December 1922 to January 1923 there were no visitors to the grave and the researchers were able to continue their work. Only on December 22, 1922, there was a brief interruption when the tomb was opened to the Egyptian and European press and important personalities.

On February 16, 1923, the actual burial chamber was opened in the presence of a high-ranking audience, including Lord Carnarvon and his daughter. The burial chamber was almost completely filled with a gilded wooden shrine , the walls were decorated with religious motifs on a gold-colored background.

Another “official” grave opening for visitors took place on February 18, among them the Queen of the Belgians , Elisabeth Gabriele Duchess of Bavaria . The press was invited the next day, and more and more visitors kept arriving on the following days until the grave was closed on February 26, 1923.

On April 5, 1923, Lord Carnarvon died and the story of a "curse on the Pharaoh" began. The finds, for the grave of Tutankhamen is famous today, were at that time still pending: The four gilded shrines that the outer quartzite - sarcophagus and the mummy contained Tutankhamun were opened only in the next digging season (1923/1924) and reduced. Work on the nested and gilded coffins took place in October 1925 and the death mask and mummy were found. Work on the treasury did not begin until October 1926.

Press and reporting

Immediately after the grave was discovered, there were numerous rumors about the find. To end this, Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon decided to "officially" open the tomb (or "opening") on November 29, 1922. In addition to British and Egyptian officials, the Cairo correspondent for the London Times , Arthur Merton, was invited, who later joined the excavation team as a press agent. Charles Breasted reported in memories of his father, the historian James H. Breasted , who was also involved , that Carter actually preferred the Egyptian and foreign press, but Carnarvon prevailed in favor of the "gentleman" from the Times . The first exclusive coverage of the official opening of the grave took place on November 30, 1922 by the London Times . The Reuters news agency was only able to bring breaking news about this one day later, on December 1, 1922. In Germany, the first press report about the discovery of the grave appeared on December 7, 1922 in the morning edition of the Berliner Vossische Zeitung . The sensational reports of alleged treasures worth several million pounds sterling finally resulted in a great rush of the world press in the Valley of the Kings .

The increasing flow of visitors in the course of the excavation and the large number of journalists who wanted to be provided with first-hand information on site, more and more hindered the archaeological work. Lord Carnarvon complained to Sir Alan Gardiner about the media's search for sensation and the reporters surrounding him. Another conversation with Gardiner finally followed on January 9, 1923, the conclusion of an exclusive contract with the London Times for £ 5,000 and three quarters of the profits to other newspaper publishers. In June 1923 the income was already 11,600 pounds sterling.

Any first-time reporting on all events in and around grave KV62 was carried out exclusively in the London Times through the exclusive contract . All other press agencies, including the Egyptian one, got their information from London before they could publish reports on the grave themselves. As the work on the grave progressed, the press agencies and journalists became increasingly dissatisfied. Some assumed Lord Carnarvon was addicted to profit. He countered that the contract only compensated him to a small extent for his financing of the excavation.

The press and public relations work increasingly overwhelmed Howard Carter. It was mainly the journalists who annoyed him, who had no access to the burial chamber because of the contract with the Times and who turned the smallest piece of news into a bombastic report. For example, a message from the Times turned into a storm in the Valley of the Kings: "Panic spread / Serious concern that tomorrow, priceless antiques will be totally destroyed."

Among the correspondents from disadvantaged newspapers present was Arthur Weigall , who now wrote for the Daily Mail . Before the First World War he had worked as an Egyptologist and had taken over the post of inspector general of the antiquities administration of Upper Egypt from Carter. He then worked as a set designer and was also successful as a writer and songwriter in show business. According to T. G. H. James , Weigall's appearance in Luxor or at the excavation site significantly promoted the hostile atmosphere between the press, archaeologists and Carnarvon.

Origin of the curse

Occultism, Spiritism and Superstition

The main reason for the public's interest in Ancient Egypt were numerous artifacts that were brought out of the country to Europe or America. The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 increased interest. With the opening of the burial chamber in 1923, the already existing Egyptomania increased. The great interest in the supernatural , the occult and the Egyptian religion prepared a good breeding ground for believing in a curse . Spiritist meetings were part of social events. Even Lord Carnarvon was a member of the London "Spiritist Society". For example, the hieroglyphic texts and magic spells were now accessible to everyone through Champollion's translations, but there were no explanatory comments on them. This led to numerous misunderstandings and misinterpretations of the contents of Egyptian theology . In addition, there was the resentment and discomfort about the archaeologists who opened a grave here and apparently disrespected the dead and desecrated the grave. In this context, there were uncertainties as to whether the ancient Egyptians might not have undreamed-of powers that were supposed to protect the dead.

The clay tablet

A mysterious clay tablet, which is said to have been found when Howard Carter opened Tutankhamun's tomb (KV62) and which is said to have had a curse on it, finally started the story of the curse due to subsequent events and general superstition. There are different accounts of the location of this clay tablet in KV62: On the one hand, it is said that it was at the feet of the two grave guard figures in the anteroom of the grave (at the passage to the burial chamber?); another time she was found at the grave entrance (November 4, 1922 or later).

The translation of the inscription on the tablet was u. a. Attributed to Sir Alan Gardiner . Gardiner arrived in Luxor on January 2, 1923 and examined the texts found in the antechamber from the following day. His translation of the inscription is said to have read:

- Death shall come on swift wings to him that toucheth the tomb of the pharaoh.

Translated:

- Death will come on swift wings to anyone who disturbs Pharaoh's rest.

Somewhat different is also indicated:

- Death is supposed to slay those who disturb the rest of the Pharaoh with his wings.

After that, the clay tablet disappeared and nobody saw it again. According to other authors, however, the tablet never existed. Archaeological science considers it to be a pure invention, as there are no photos of it, although the finds in the grave were documented photographically and registered with find numbers. Howard Carter's notes also contain no notes on such a clay tablet.

Philipp Vandenberg writes without citing the source that the clay tablet was deleted from the logs of the excavation out of consideration for the superstition of the local workers and has since been lost. The curse also appears again in a modified form on the back of a magical figure in the main chamber: it is I who rejects the grave robber with the flame of the desert. It is I who protect the tomb of Tut-ench-Amun.

The choice of words and wording are in comparison to other Egyptian texts, which are to be regarded as grave curses, atypical and therefore rather un-Egyptian. The picture of "Death with wings" drawn here would be covered for the first time with this clay tablet.

Further variants of the inscription

The clay tablet is the most famous object on which the curse is said to have stood. According to other contemporary reports, the curse inscription was on "other" objects.

- A newspaper published at the time that the curse could be read in hieroglyphics on the door of the second shrine next to a winged creature and that it read: "Whoever enters this sacred grave will be hit by the wings of death." However, the inscription on this shrine speaks nothing of the kind.

- Another story published in the press is that of a magician who described himself as an archaeologist. According to him, there was a stone at the entrance to the tomb with a curse carved into it, which read: “Let the hand that rises against my building wither! Those who attack my name, my foundation, my likeness and images of me will be left to be destroyed! ”Howard Carter took this stone and buried it.

- A reporter picked up the inscription on the ceramic base of the candle from the Anubis Shrine : “I will keep sand from filling the secret chamber. I am there to protect the dead. ”He wanted to read from it a warning for the excavation team and emphasized the whole thing with his own lines:“ And I will kill all who cross this threshold to the sanctuary of the King of Kings, who lives forever. "

- In its October 2007 issue, PM History magazine attributes the words to the hieroglyphic inscription (without specifying sources) but also to the occultist Marie Corelli (see below).

The events

The alleged clay tablet with the curse, superstition , the sum of the events and the circumstances during and after the opening of the tomb were ultimately what gave rise to the story of the curse of Tutankhamun and the curse of Pharaoh . The press coverage was exaggerated by twisting facts and adding their own fantasies to the journalists. The information about the events is also very different in the literature, which reports more or less in detail about the stories about the curse. The descriptions differ in the information on the respective persons, the individual circumstances and in the information on the time of death, the cause of death and the age of individual persons. But even decades after the grave was discovered, some deaths or mysterious events were still associated with the grave and the curse.

- Howard Carter's canary is said to have fallen victim to a cobra on the day the grave was opened in Carter's house . This was of particular importance to the locals: snakes, especially the erect cobra, were considered to be the pharaoh's protectors in the form of the uraeus snake . Locals saw a bad omen in the bird's death, a sign of punishment for opening the tomb.

- This variant is supported by a report in the New York Times dated December 22, 1922, of a visit from their correspondent to the antechamber. The bird perished on the evening of the same day (November 27, 1922), on which the two guard figures entered this room at the entrance to the burial chamber. " Incidentally, the day the tomb was opened and the party found these golden serpents in the crowns of the two statues there was an interesting incident at Carter's house. He brought a canary with him this year to relieve his loneliness. When the party was dining this night there was a commotion outside on the veranda. The party rushed out and found that a serpent of similar type to that in the crowns had grapped the canary. They killed the serpent, but the canary died, probably from fright. The incident made an impression on the native staff [...] "

- James H. Breasted , whose presence Carter noted on December 19 and 20, 1922, however, reported that a messenger that Carter had sent to his house had heard the "death cry" of the bird attacked by the cobra on his arrival there.

- Thomas Hoving , former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York , reports that when Carter drove to Cairo to pick up Lord Carnarvon (November 18-22, 1922), Callender lived alone in Carter's house with the task of making himself special to take care of the canary, adored by all. One afternoon […]

- One day in February 1923, when Lord Carnarvon was entering the tomb, Arthur Weigall jokingly remarked to another reporter: "When I see the mood he's going down in, I'll give him six weeks to live." Six weeks after that statement the lord dead.

- Two weeks before Lord Carnarvon's death, the occultist and novelist Marie Corelli (pseudonym for Minnie MacKay) issued a warning: "The most dire punishment follows any rash intruder into a sealed tomb." . ”) Or rather it was not an explicit statement by Corellis, but a fictional letter from a book manuscript of her, which the magazine New York World published.

- At the time of Lord Carnarvon's death, at about 2:00 am, came across Cairo to the current , and in died the same night, supposedly at death Carnarvon, Highclere Castle whose pet dog Susie . Thereafter, the story of the Pharaoh's curse gained international impetus. Lord Carnarvon died two weeks after Marie Corelli's "Warning".

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle , author of the Sherlock Holmes stories and a believer in spiritualism, spoke about the events in an interview the day after Lord Carnarvon's death. The Morning Post quoted him as saying, “It is possible that something elemental evil is causing Lord Carnarvon's fatal illness. One does not know which spirit beings existed at that time and in what form they appeared. The ancient Egyptians knew much more about these things than we did. ”Doyle is also said to have said that an Egyptian mummy could emit“ devastating rays ”.

- In addition, after Carnarvon's death, Arthur Weigall revived the idea that a misfortune emanated from ancient Egyptian graves. Nicholas Reeves quotes Rex Engelbach , then General Inspector of Antiquities: "When my wife and I complained to Weigall, he said: But look how the public pounces on it!"

On the other hand, the team is said to have made little effort to counter the rumor of the "curse" in the hope that this idea would scare off disturbing or stealing visitors.

Deaths and extraordinary events

After the contemporary press coined the term “curse of the Pharaoh” after Lord Carnarvon's death, persons who were involved in the excavation in some way or who seemingly came into contact with objects from the tomb were assigned to this curse as “victims” Had visited the grave. All of them allegedly did not die of natural causes and under more or less mysterious circumstances. The order in which the curse hit the alleged victims is not always clearly reproduced in the literature either. The year of death is often missing. The contemporary press of the time even assigned numbering to the presumed victims. B. Arthur Weigall was considered the 21st victim to succumb to an unknown fever. In 1939, Howard Carter and the two excavation draftsmen of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lindsley Foote Hall and Walter Hauser, were among the victims.

Over the years, not only the deaths of people who had any connection to the tomb of Tutankhamun, but also apparently inexplicable incidents that occurred with regard to the tomb, its treasures or the mummy were regarded as the "curse of the pharaoh".

1923 to 1925

Deaths in 1923:

In mid-March 1923, Lord Carnarvon accidentally cut a mosquito bite while shaving . On March 21, Carter found him in Cairo with blood poisoning and erysipelas . On March 26th came pneumonia , which, according to the death certificate, led to the death of the Lord - who had been suffering from lung disease for a long time - on April 5th, 1923. He died at the age of 56. Rumors later circulated that Tutankhamun's mummy had a wound on the face in the same place.

The American millionaire and friend of Lord Carnarvons, George Jay Gould I , visited the tomb and caught a cold. He died a short time later on the French Riviera of the resulting pneumonia . According to other reports, he died in Egypt on the same day or a day later. Gould died on May 16, 1923 at the age of 59 in his villa in France. According to the New York Times, his death from prolonged illness was not unexpected.

Deaths in 1924:

Gardian La Fleur , a literary scholar at McGill University in Canada, visited the grave and died two days later. His companion and assistant committed suicide by hanging and blamed the Pharaoh's curse in his suicide note.

The radiologist Archibald Douglas Reid examined Tutankhamun's mummy and allegedly collapsed. He had suffered from radiodermatitis for several years and later died of pulmonary congestion and an unknown fever. According to another source, he died at the site.

Deaths in 1925:

The half-brother Carnarvon, Colonel Aubrey Herbert, was present during the opening of the sarcophagus in October 1925, died a few weeks later at a peritonitis . According to other reports he committed due to a depressive attack suicide .

The British industrialist Joel Woolf visited the grave and fell overboard and drowned on the voyage to Luxor. According to another account, on the way back to England he passed out and died.

HG Evelyn-White, an Egyptologist from the University of Leeds, studied Egyptian papyrus scrolls in a Coptic monastery . After returning from Egypt, he committed suicide. According to his suicide note , he suffered from deep-seated fears and believed that after studying the scrolls, a curse lay upon him.

1926 to 1928

In 1926 , Georges Bénédite , chief curator of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris, allegedly died on the same day that he first entered the tomb. After visiting the grave, he suffered fatal heat stroke or died of a stroke . Another report is that he died of a fall after entering and leaving the grave.

Two years later , Arthur C. Mace , curator of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and Howard Carter's right-hand man, allegedly died of a strange illness. In fact, Mace was at a recurring before the start of excavation pleurisy ill and finally succumbed this disease. As a result, he had stopped working in the valley in 1924. He died at the age of 53.

1929 and 1930

Howard Carter's secretary, Richard Bethell, was found dead in his apartment in 1929 at the age of 35. Suicide is now considered likely because he was in excellent health the night before. However, suicide could not be proven. On the other hand, it is said that he died under mysterious circumstances in the Bath Club or of circulatory failure .

In the same year, Carnarvon's wife Lady Almina was infected by an insect bite and died a short time later. Carnarvon's friend and executor, John G. Maxwell, also passed away that year.

Ali Fahmy Bey posed as an Egyptian prince and claimed to be of direct descendants of Tutankhamun. He was found murdered in his hotel room at the Savoy Hotel in London and was apparently shot by his wife. A short time later, his brother committed suicide.

A year later, in February 1930, Bethell's father, 78-year-old Lord Westbury, threw himself out of the window of his London domicile. Whether it was a suicide or an accident could never be unequivocally clarified. The hearse was involved in an accident on the way to the cemetery, killing a child. There were alabaster vases belonging to Tutankhamun in Westburys apartment and his death was thus linked to the curse .

That same year, Lord Carnarvon's half-brother, Mervyn Herbert, died unexpectedly at the age of 41.

1966 and 1968

In 1966 , Dr. Mohammed Ibrahim, director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , prevent his government from hosting an exhibition of pharaonic treasures in Paris . He had dreamed that he would die in a car accident at the beginning of this exhibition. Ibrahim was run over by a car in front of his museum in Cairo and died two days later from his injuries.

1968 RG Harrison led by the University of Liverpool X-ray examinations of the mummy of Tutankhamun. While working in the Valley of the Kings, "strange incidents" occurred that were not specified, and the power went out in Cairo. A person closely related to the research team, whose name Harrison would not reveal, passed away.

1992 and 2005

When a BBC film team made a documentary about Tutankhamun in 1992, strange accidents occurred time and again at the original locations.

With the examination of Tutankhamun's mummy by means of a CT scan in 2005, there was again talk of the curse of the pharaoh in this context, as the mummy had to be removed from the grave for this. It shouldn't be exposed to daylight; Moreover, many Egyptians had for fear of the curse on the investigation protests . Therefore the examination took place at night. The investigation team actually experienced some inconveniences: a sandstorm broke out; it started to rain, which is rare in this region; the car with the computer tomograph nearly had an accident and the device itself failed for two hours.

More victims

Another victim among many was the friend of a tourist who had entered the burial chamber and was run over by a taxi in Cairo. The curator of the British Museum's Egyptian Department was also one of the alleged victims of the curse, even though he died in his bed. An employee of the British Museum allegedly dropped dead while labeling items from the grave. However, there are no items from Tutankhamun's tomb in this museum - and never have been.

Effects of believing in this curse

The curse of the Pharaoh dominated the global press in the aftermath of the opening of the tomb and Lord Carnarvon's death, sparking incidents that bordered on hysteria. Although there was no cause for general alarm, the British Museum received many parcels containing Egyptian antiquities afterwards. A large number of the senders said that Carnarvon was certainly killed by the Ka Tutankhamun. Although a spokesman for the museum announced that these fears were completely unfounded, the Egyptian section of the museum continued to receive Egyptian artifacts , as well as the hands and feet of mummies.

Conjectures and theories

Not only were the death dates of those associated with the grave examined and analyzed, but scientific explanations for the "accumulations of deaths" were also sought.

As a cause of Lord Carnarvon's death, besides the curse, poison was suspected that had been applied to grave objects. This theory goes back to Ralph Shirley of the Occult Review . As early as the 1920s, articles reported deadly bacteria in the grave that are believed to have led to Carnarvon's death.

In his book The Curse of the Pharaohs, Philipp Vandenberg gives examples of the possible knowledge of the ancient Egyptians about antibiotics , herbal poisons , intoxicants and bacteria . Not only this knowledge could have served to secure the royal tombs, but the Egyptian priests would have acquired special knowledge over the centuries that would have led to changes in the protective systems in the tombs. So the curse does not necessarily have to be due to known agents such as deadly poisons. The fact that Haremhab left Tutankhamun's tomb untouched, for example , is a decisive point for him in this respect: poison or bacteria in the tomb would not have prevented the last king of the 18th dynasty from plundering the tomb. Vandenberg sees this as an indication that there was a security system for graves and mummies at the time of the pharaohs, in which the possession of such grave objects would have fatal consequences.

In 1949, the atomic physicist Louis Bulgarini made the claim that the ancient Egyptians had already known about atomic decay and used the radiation generated to protect the graves - similar to what Doyle had already suspected.

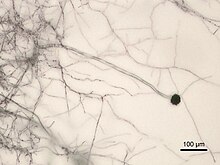

As early as 1962, Dr. Ezzeddin Taha found a connection to the Aspergillus niger mold . The best-known and more recent theory, however, is that of Aspergillus flavus , which became very well known in the 1980s through the Terra X documentation series . Because of its life-threatening effects, the fungus was brought into the tomb by the ancient Egyptians to protect it. According to the theory, the fungi of the Aspergillus group, which were not only found in Tutankhamun's tomb, are responsible for all illnesses and deaths of the various epochs in connection with worldwide grave openings.

Explanations and Refutations

After Carnarvon's death, the contemporary press forced the notion of the "curse" due to various statements made during the ongoing work on the tomb of Tutankhamun. At that time, in the years that followed, and in the present, there were proponents of the supernatural on the one hand, and skeptics on the other , who conduct research, scientific research, and statistics against the alleged existence or effectiveness of the curse.

Analysis of the death dates

The German Egyptologist Georg Steindorff worked out in a monograph in 1933 that most of the victims associated with the curse died between the ages of 70 and 80. The Australian researcher Mark Nelson from Monash University, in turn, analyzed the résumés and team memberships of Carter's employees from 1923 to 1926. He came to the conclusion that those actively involved in the excavation of the grave were exposed to no higher risk than those who only took part in the expeditions. There is no indication that the excavations had a negative effect on the expected lifetime of the “grave robbers”. Rather, the British press has succumbed to its addiction to sensation by taking up the ideas of Louisa May Alcott's novel Lost in a Pyramid: The Mummy's Curse and similar literary works .

The American Egyptologist Herbert E. Winlock , director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1932 to 1939 , compiled statistics on the events and deaths in 1934. These records contained the date and cause of death and showed a completely different picture of the time periods after the tomb was opened. After every new newspaper report that there was a new victim of the curse, he sent a correction to the relevant newspaper. Of the 26 people present when the grave was opened, six died within 10 years; of 22 people who were present at the opening of the sarcophagus, two died; out of 10 people present when the mummy was unwrapped, none succumbed to the "curse".

Howard Carter died in 1939 at the age of 64; Harry Burton , the photographer, died in 1940 at the age of 60; Lady Evelyn, Lord Carnarvon's daughter, who was one of the first to enter the tomb and who also attended the opening of the burial chamber, died in 1980 at the age of 78. Other members of the excavation team also had long lives: Percy E. Newberry , a friend of Carter's and his mentor, died in 1949 at the age of 80; Sir Alan Gardiner, who studied the funerary inscriptions, died in 1963 at the age of 84.

Scientific considerations

Basically, accumulations of toxic gases or pathogens ( mold spores as germs or rather as allergens ) come into consideration and are also taken into account in practice. However, it is doubtful that visitors to the grave or participants in the investigations would have died for such reasons. According to the statistical considerations, and since the causes of death of those involved are mostly known and not unusual, there is also little need for explanations based on the nature of the grave and the mummy.

Aspergillus flavus / niger: The Australian black mold researcher John Pitt explains: “In any case, it is impossible that the spores can survive in a dry grave for just a hundred years. In addition, Aspergillus spores are really to be found everywhere, and if they are found, they could have contaminated the grave at any time. ” The mold can indeed settle in the human body permanently if it is inhaled over a long period of time, but then only if the person concerned was sick before.

Poisons: The theory of poisons in the grave was questioned as early as the 1920s by Algernon Blackwood , a widely read writer: “How come the poison only worked on one person?” That question was followed by the next theory : the high priests should have painted poison on some grave goods - and Lord Carnarvon of all people had touched one of these objects. A French professor found Howard Carter guilty of Carnarvon's death and explained why Carter was not also affected by the curse: He was an expert who knew which objects in the grave could and could not be touched.

Radiation: Radioactivity in the grave or on objects in the grave could not be detected.

Rational explanations for what happened after Carnarvon's death

- The canary had by no means been devoured by a cobra on the day the coffin was opened: Howard Carter had taken care of the animal with a friend.

- Power outages in Cairo were still very common decades after Lord Carnarvon's death. The fact that the time of his death coincided with a power failure gave the event something mysterious, but it was a coincidence and had nothing to do with his death.

- Carnarvon's dog did not die at the same time as the lord, but probably only four hours later.

- About Douglas E. Derry, who examined Tutankhamun's mummy, and Alfred Lucas, the chemist on site in the Valley of the Kings, who assisted Derry, was reported: “The autopsy of Tut-ench-Amun on November 11, 1925 in the anatomical institute of Cairo The university had tragic consequences: Alfred Lucas soon died of a heart attack. A little later, Professor Derry, who had made the first incision on the Tut-ench-Amun mummy, died of circulatory failure. ”(Vandenberg) In fact, both of them only died many years later. Derry died in 1969 at the age of 87, Lucas in 1945 (or 1950) at the age of 79.

- Tutankhamun's mummy had no facial lesions that would indicate a mosquito bite.

- Almost all of the alleged victims were elderly or had health problems before they traveled to Egypt. Lord Carnarvon, for example, had been a sick man since a car accident in Germany in 1901, who regularly traveled to Egypt to recover and strengthen his health. George Jay Gould, a friend of the Lord, was also ill before his stay in Egypt and traveled to the country to relax. Howard Carter himself suffered from various health problems, including headaches and circulatory problems, from the excavation until his death (1939).

rating

Howard Carter already commented on the stories about the curse with the words: "[...] all sane people should dismiss such inventions with contempt." ("All people of common sense should reject such inventions with contempt.")

Thomas Hoving , former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York , wrote in 1978: “Apart from this general warning in the treasury, no real curse had been found in the tomb of Tutenkh Amun - nor was one to be expected "; and further: “If there ever was a curse, it was neither written in hieroglyphics nor expressed in pictures. It did not come from the mouth of the Pharaoh and was also not pronounced by the priests of the New Kingdom. It did not penetrate certain objects as an immortal poison, but was born of human weakness, as is so often the case in the wake of astonishing discoveries of immeasurable treasures. "

Despite evidence of natural explanations of the events and deaths and correct representations of the circumstances, allusions to the curse of the Pharaoh are still made today when it comes to events connected with Tutankhamun's tomb. Renate Germer describes this very aptly: “It is probably a matter of conviction whether one believes in the effectiveness of such curses or not. In any case, there were no texts in Tutankhamun's tomb that pronounced such a curse. "

To the incidents in connection with the CT examination of Tutankhamun, Zahi Hawass commented twice on the curse of the pharaoh: " I think we should still believe in the curse of the pharaohs , he said from the tomb of Tutankhamun"; and the question of whether he too was afraid of the Pharaoh's curse he answered another time with a silence. Hawass is said to have had strange experiences with mummies himself.

The "curse" in literature and film

"Curses from ancient Egypt" were a topic in literature even before the Tutankhamun tomb was discovered. The English writer Jane C. Loudon published her novel The Mummy in 1828 , which is about a mummy's campaign for revenge in the 22nd century. In 1869, the American writer Louisa May Alcott built on it with her novel The Curse of the Mummy . In 1890 the short story appeared in The Ring of Thoth (dt. The Ring of Thoth ) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in which it comes to a mummy and strange happenings in the Louvre. In 1910 the novel The Mummy moves by the Australian Mary Gaunt was published .

After the discovery of the tomb and the events that subsequently led to the story of the "curse of the Pharaoh", this topic continued to be present in literature. So grabbed Agatha Christie contemporary the subject of a curse associated with the opening of a royal tomb two years after the discovery of KV62 in the published 1924 short story The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb (Engl. The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb ) with Hercule Poirot on. In this story she even briefly mentions the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. In the 1970s, Victoria Holt thematized with The Revenge of the Pharaohs and Jean Francis Webb with Carnarvon's Castle stories about ancient Egyptian curses.

Numerous films also took up the subject of curses and mummies. The best-known horror film from the time of the work on Tutankhamun's tomb is The Mummy with Boris Karloff from 1932. In 1999, this film was reprinted with Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz , which in 2001 with The Mummy Returns and in 2008 with The Tomb of the Dragon Emperor was continued. A film that makes reference to King Tutankhamun and the clay tablet is King Tut - The Curse of Pharaoh (2006).

Jokingly modified meaning

The traveler's diarrhea (traveler's diarrhea) is jokingly called "Curse of the Pharaoh" when applied to tourist Egypt travel occurs. The cause is simply toxins from various bacteria , which are more common in the travel destination than in the home of the tourists. Another favorable factor is the association with inadequate hygiene . When traveling to Central and South America , one speaks instead of " Montezuma's revenge".

literature

- Arnold C. Brackman , Susanne Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0333-9 .

- CW Ceram : Gods, Graves and Scholars. Archeology novel. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1967.

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt : Tut-ench-Amun. Gutenberg Book Guild, Frankfurt 1963.

- Ulrich Doenike: The Revenge of the Mummy: Myth and Truth . In: PM History , October 2007, pp. 58-62.

- Zahi Hawass : Discovering Tutankhamun. From Howard Carter to DNA. The American University Press, Cairo 2013, ISBN 978-977-416-637-2 , pp. 214-217.

- Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Droemer Knaur, Munich / Zurich 1978, ISBN 3-426-03639-8 .

- Gottfried Kirchner: TERRA X puzzles of ancient world cultures: The curse of the Pharaoh . Bertelsmann, Frankfurt 1986, Book No. 02353.

- Christine El Mahdy : Tutankhamun. Life and death of the young pharaoh . Blessing, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-89667-072-7 .

- Nicholas Reeves : The Complete Tutankhamun . Thames & Hudson, London 1995, ISBN 0-500-27810-5 , pp. 62-63.

- Joyce Tyldesley : Myth of Egypt . Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-15-010598-6 .

- Philipp Vandenberg : The curse of the pharaohs. Modern science on the trail of a legend . Scherz, Bern (no year), order no. 073254.

- Philipp Vandenberg: The forgotten Pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun company - the greatest adventure in archeology . Bertelsmann, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-570-03119-5 .

Web links

- National Geographic : Tutankhamun's curse caused by poisons in the grave? (English)

- ZDF: "Company Tutenchamun" in a new light ( Memento from January 28, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- Mark Benecke: Finally peace in the sarcophagus. Accessed February 16, 2020 . , 15./16. September 2001.

- The Mummy's Curse (Curse of the Mummy) on touregypt.net (engl.)

Remarks

- ↑ This happened on January 3, 1924 or was adjusted for inclusion on January 4, 1924. The photographer was Harry Burton on behalf of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (cf. KV62 ). In the selection of the Griffith Institute (Oxford), the recording (referred to as p0643 ) is dated January 4, 1924. According to Carter's diary , the doors of the third and fourth shrines were opened on January 3, 1924, and Burton was also present (see "Mace's diary" for details). However, Burton's recordings of the doors and the sarcophagus are only recorded for January 4th.

- ↑ No exact date or event is given either in the press or in various literature. Also, comparatively often only coffin opening is mentioned in this context. Between November 5, 1922 and February 16, 1923, five different days come into question as "day of the opening of the grave". Including the first breakthroughs in the respective doorways. There is also the English term official opening for dates on November 29, 1922 and February 18, 1923, which should not be translated as a grave opening, but as an opening or the like. Opening (of) the tomb can therefore apply to seven days.

- ↑ In the printed literature, also in Howard Carter's publication Das Grab des Tut-ench-Amun. (Wiesbaden 1981), p. 91, February 17 , 1923 is indicated instead , apparently based on the representation by Carter and Mace, where Friday, February 17, 1923 is indicated. Carter and Mace , on the other hand, list Friday, February 16 in their records . In fact, the 16th was a Friday, not the 17th in a letter. Accessed February 16, 2020 . Gardiner describes the event to his mother on February 17 , 1923 - Yesterday . Finally, one finds the note from the Griffith Institute (at the bottom): This text has also been published in Discussions in Egyptology 32 (1995), but the electronic version has been revised and updated. (November 8, 2004)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Nicholas Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun . London 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, p. 202.

- ^ Curse of the mummy's tomb invented by Victorian writers , The Independent, December 31, 2000

- ↑ a b c d e Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, pp. 182-184.

- ↑ Hans Bonnet: Lexicon of Egyptian Religious History , p. 195.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1 , p. 54.

- ↑ a b c d Howard Carter's diary October 28 to December 31, 1922

- ↑ a b This and quotes from Carter, which express his enthusiasm, also on the English-language Wikiquote

- ↑ a b c Translation by the editor

- ↑ a b cf. How The Times reported the discovery of Tutankhamun. ( Memento of June 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) On: Times Online. dated June 26, 2008.

- ↑ a b c d Howard Carter's Diary 1923 (January 1 to May 31)

- ↑ cf. Entry in Carter's diary on October 23, 1926

- ^ Charles Breasted: Pioneer to the Past. The Story of James Henry Breasted, Archaeologist. University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London (1977) [1943], ISBN 0-226-07186-3 (paperback).

- ↑ The Pharaoh's Throne. The treasures in the magnificent tomb of Luksor. In: Vossische Zeitung . No. 578, morning edition. Thursday, December 7, 1922, p. [5].

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 119.

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 125.

- ↑ Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, p. 128.

- ^ How The Times dug up a Tutankhamun scoop and buried its Fleet Street rivals. On: Times Online. dated November 10, 2007.

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 131.

- ↑ TGH James: Howard Carter: the path to Tutankhamun. Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2006 (revised paperback edition of a Carter biography originally published in 1992), p. 279.

- ↑ a b c Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, pp. 153-154.

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley: Myth of Egypt. Stuttgart 2006, p. 240.

- ↑ a b c Gottfried Kirchner: The curse of the Pharaoh - The secret knowledge of the ancient Egyptians. In: TERRA X puzzles of ancient world cultures. Pp. 24, 36.

- ^ The New York Times, December 22, 1922 , accessed May 17-20. August 2009

- ↑ a b c d Howard Carter's Diary 1922 (October 28 to December 31)

- ↑ a b Ulrich Doenike: The revenge of the mummy: Myth and truth . In: PM History , October 2007, pp. 58-62.

- ↑ Howard Carter's Diary 1923 (January 1 to May 31)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Nicholas Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun . London 1995, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ a b c C. W. Ceram: Gods, graves and scholars . Hamburg 1967, p. 203.

- ↑ Philipp Vandenberg: The curse of the pharaohs. Modern science on the trail of a legend . P. 20.

- ↑ a b c Renate Germer: Mummies. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96153-X , p. 64.

- ↑ Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, p. 58.

- ↑ Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, p. 159.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Mark Benecke: Finally peace in the sarcophagus. Accessed February 16, 2020 . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 15./16. September 2001.

- ↑ a b John Warren: The Mummy's Curse (Curse of the Mummy) on touregypt.net (English) (seen August 23, 2009)

- ↑ Ulrich Doenike: The Revenge of the Mummy: Myth and Truth. In: PM History , October 2007, p. 59.

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves: Fascination Egypt. P. 165

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves: The Complete Tutankhamun . London 1995, p. 63.

- ^ A b Philipp Vandenberg: The forgotten Pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun company - the greatest adventure in archeology . Munich 1978, p. 179.

- ^ Archives of the New York Times , May 17, 1923

- ↑ Obituary: Sir Archibald Douglas Reid . In: British Medical Journal (Br Med J) . 1, No. 1136, January 1924, p. 173. doi : 10.1136 / bmj.1.3291.173 .

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 210.

- ^ Christiane D. Noblecourt: Tut-Ench-Amun. Frankfurt 1963, p. 20.

- ↑ a b c Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, p. 183.

- ↑ Philipp Vandenberg: The forgotten Pharaoh. Tut-ench-Amun company - the greatest adventure in archeology . Munich 1978, p. 180.

- ↑ Philipp Vandenberg: The curse of the pharaohs. Modern science on the trail of a legend . Bern (no year), p. 28.

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, pp. 219-220.

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 220.

- ↑ a b The Tutankhamun murder case. On: Abendblatt.de of January 7, 2005.

- ↑ a b Pharaohs' Curse Released During Tutankhamun Scan? On: arabnews.com of January 8, 2005.

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 153.

- ↑ Philipp Vandenberg: The curse of the pharaohs. Modern science on the trail of a legend . Bern (no year), pp. 208–209.

- ^ Mark R. Nelson: The mummy's curse: historical cohort study. In: British Medical Journal. 2002, Vol. 325, pp. 1482-1484.

- ↑ National Geographic: Curse of Tutankhamun caused by poisons in the grave? (English)

- ↑ See last sections of: John Warren: The Mummy's Curse (Curse of the Mummy) on touregypt.net (engl.)

- ↑ Thomas Hoving: The golden pharaoh Tut-ench-Amun. Munich / Zurich 1978, p. 184.

- ↑ Warren ( The Mummy's Curse (Curse of the Mummy) ) provides the content is short.

- ↑ The Ring of Thoth ( Memento of October 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, S. Karges: They found the golden god. The tomb of Tutankhamun and his discovery. Augsburg 1999, p. 207.