Chaba pyramid

| Chaba pyramid | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ruin of the layer pyramid

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

The Layer Pyramid (also layer pyramid of Chaba and layer pyramid of Zawyet el'Aryan called, often with the English name Layer Pyramid ) is an ancient Egyptian grave pyramid , which in the necropolis of Zawyet el'Aryan in Egypt is. Locals call them il-haram il-midawwar ( Arabic for "rubble pyramid").

The builder of the Chaba pyramid is unknown, but since its tomb architecture is very similar to that of the pyramid of the king ( pharaoh ) Sechemchet , it is consistently dated to the 3rd dynasty of Egypt (epoch of the Old Kingdom ). The Chaba pyramid was excavated at the beginning of the 20th century, but no artifacts or remains of a burial could be found. For this reason, current research is debating whether the building was left unfinished or whether the builder died prematurely and found his final resting place elsewhere. Because some Egyptologists suspect King Chaba behind the monument, the layer pyramid is commonly called the Chaba pyramid or layer pyramid of the Chaba .

Exploration and excavation history

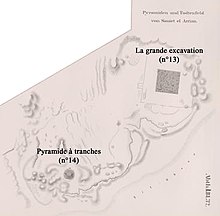

The Chaba pyramid and its immediate surroundings were first examined by the British Egyptologist and anthropologist John Shae Perring around 1839 . In 1840 the pyramid was recognized as such by the German researcher Karl Richard Lepsius and cataloged as Pyramid XIV in his list of pyramids . Around 1886, the French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero searched unsuccessfully for the entrance to the pyramid. This was discovered in 1896 by the (also French) archaeologist Jacques de Morgan . De Morgan exposed the first few steps to the underground tomb complex, but ended his work without giving any further reasons.

The Italian archaeologist Alessandro Barsanti undertook further investigations in 1900. He exposed the vertical access shaft to the burial chamber and some of the side corridors. When Barsanti discovered that there were apparently no grave goods and / or burial traces, he immediately voiced the suspicion that the Chaba pyramid had never been used. Only a little later, from 1910 to 1911, the American archaeologists George Andrew Reisner and Clarence Stanley Fisher investigated the pyramid district and excavated the northern and eastern flanks of the pyramid and large parts of the associated cemetery. On the north side of the pyramid they came across a breach leading to the core of the pyramid, which was probably created during an earlier exploration by Vyse and Perring and allowed an insight into the masonry structure. In the 1960s, V. Maragioglio and CA Rinaldi also examined the truncated pyramid of the Chaba pyramid in detail.

Today the Chaba pyramid lies within a restricted military area, which is why no extensive excavations have taken place since the 1960s. The building is now completely silted up and one can only speculate about the state of preservation and architectural details, since neither can be checked.

allocation

Dating

The architecture and construction of the Chaba pyramid is very similar to that of the pyramids of kings Djoser and Sechemchet. According to Rainer Stadelmann , Miroslav Verner and Jean-Philippe Lauer , the complex shows both architectural improvements and advances compared to the previous pyramids, on the other hand simplifications in construction, structure and complexity can be seen. According to the researchers, the entire complex is visible as an advanced version of the Sechemchet pyramid. For this reason, the Chaba pyramid is unanimously dated to the 3rd dynasty, more precisely: to the period between the kings of Sechemchet and Sneferu (founder of the 4th dynasty ).

Client

The identity of the actual builder of the pyramid has not yet been clarified . Much of today's research assigns the building to a king named Chaba , of whom only Horus and Gold names are known so far . The reason for this assignment is the explanations of Rainer Stadelmann, who equates Chaba with the cartouche name of another ruler: Huni . According to a few contemporary artifacts and Ramessid king lists, this king also ruled in the 3rd dynasty. According to one of these sources, the Royal Papyrus Turin , Huni ruled for 24 years and left behind important structures. According to Rainer Stadelmann, this time span fits a structure like the layer pyramid, especially since he assumes that it was completed and used as a grave. He also points out that in a nearby mastaba , mastaba Z500 , stone vessels and clay seals with the Horus name of Chaba were found. Mark Lehner is speculatively considering the possibility that Chaba could also have been buried in Mastaba Z500 instead of the pyramid.

location

The Chaba pyramid is located near the Saujet el-Arjan necropolis , about 8 km southwest of Giza and 7 km north of Saqqara . It has been in the northwest sector of a restricted area of the local military since around 1960 and is bordered by bungalows to the south . The monument rests on a rock plateau just above sea level.

architecture

Grave superstructure

The Chaba pyramid has an almost square base of 84 × 84 m. It is only slightly smaller than the pyramids of Djoser and Sechemchet. Based on comparisons with the previous pyramids, Lauer assumes that they have five steps and should reach a height of approx. 42–45 m. Today only two steps with a total height of about 17 m remain, which are buried under considerable mounds of rubble. The ruinous condition of the pyramid allows a view of the pyramid core. Its basic dimension is 11 × 11 m, it consists of roughly hewn stone blocks that were broken from a local rock plateau. The core of the pyramid is in turn surrounded by a 2.60 m wide layer of roughly hewn stone blocks. This innermost layer is in turn surrounded by 14 other layers of the same type of masonry, which are held together with clay mortar. The clay brick layers are also each 2.60 m wide. All layers of the pyramid incline 68 ° inwards, towards the pyramid core. All levels of the pyramid were designed according to this concept and the construction method described. The entire grave superstructure shows no traces of limestone cladding , which is interpreted by some Egyptologists as an indication that the Chaba pyramid remained unfinished. Instead, there were remains of mud bricks that had been collected and piled up according to plan, which were clearly not directly related to the building. It is assumed that this could be the remains of the building ramp to the pyramid.

Grave substructure

The underground tomb complex is remarkably similar to that of the Sechemchet pyramid in Saqqara. For this reason alone, modern research agrees that the construction of the Chaba pyramid almost or actually immediately followed that of the Sechemchet pyramid.

The entrance to the underground complex is near the north-east corner of the pyramid. This location is a deviation from the usual positioning on the north side of pyramids of the old kingdom. The Italian Egyptologists Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi suspect that the workers wanted to release the north side of the pyramid at the time of construction so as not to disturb the construction of the mortuary temple. Aidan Dodson has doubts about this theory; in his opinion, the choice of the entrance location was purely structural: the workers wanted an access to the grave complex that would be stable and safe due to the solid rock underground. Dodson also points out that the remains of the construction ramp seem to point towards the north side - a construction ramp would, however, have impaired the erection of a mortuary temple at this point much more.

The entrance leads into a steep, 36 m long staircase that leads into a corridor facing west. This ends after about 26 m in a T-shaped crossroads with a vertical shaft that connects the corridors that meet each other directly with the surface of the earth. Near the opening, the vertical shaft has an unfinished corridor that leads south to the central axis of the pyramid. The lower end of the vertical shaft leads into a passage that leads both to the north and to the south. In a northerly direction the corridor leads into the magazine galleries, which form a U-shaped complex to the east and west. A total of 32 magazine rooms are currently known. In the south, however, the main corridor leads directly into the burial chamber of the Chaba pyramid. Halfway there, the corridor bends downwards in a staircase shape and tapers in the process. It is now so narrow that some researchers doubt that a royal sarcophagus would ever have fit through. In the notes of Alessandro Barsanti there is an illustration of another, unfinished corridor that leads away from the landing at ceiling height. However, this passage is missing in Reisner and Fisher's grave plans. Due to the current inaccessibility of the Chaba pyramid, the question must remain which excavation sketches are more correct and therefore more reliable.

The grave chamber of the Chaba pyramid is located exactly in the middle under the grave monument at a depth of about 26 m. It has a rectangular floor plan with the dimensions 3.63 × 2.65 m and has a ceiling height of around 3.0 m. All excavation reports known to date agree that the burial chamber was carefully worked out and has polished interior walls, but does not contain any traces or remains of a sarcophagus , or at least any evidence of a burial. According to Mark Lehner, the subterranean tomb complex gives the impression that the pyramid workers simply stopped in the middle of their work and went home.

Pyramidal complex

Remarkably, no remnants of an enclosing wall, such as were common for the pyramid complexes of the Old Kingdom, have been found so far. But it may also be that the walls were torn down early (stone robbery) or never started, as they usually represented the final element of a tomb. No remains of a cult or queen pyramid were discovered. On the eastern flank of the pyramid there were sparse remains of adobe walls , possibly a small mortuary temple was located here. Almost 200 m to the south-west lie the ruins of a building that some archaeologists and Egyptologists interpret as a valley temple. This is controversial, however, as the structure faces east-west, which would be unique for an Old Kingdom valley temple.

necropolis

The necropolis of Saujet el-Arjan, in which the Chaba pyramid is located, houses mostly simple burials, but also numerous mastaba graves from the 3rd dynasty . Some of them are small-sized mastabas. Interestingly, those graves that can be assigned to the late 3rd Dynasty are much larger. The largest of these are the Mastabas Z300 - Z500. According to Reisner, Fisher and Stadelmann, this indicates that relatives of a king, or at least high-ranking courtiers, must have been buried in these large graves. Since the largest grave monument, the Mastaba Z500, contained several stone vessels with the Horus name of King Chaba, many Egyptologists consider him the tomb of the layer pyramid, as it was customary in the Old Kingdom for relatives and the court to be buried in close proximity to the royal tomb has been. A few hundred meters to the northeast is the unfinished grave shaft of the so-called Baka pyramid from the 4th dynasty .

literature

- IES Edwards : The Pyramids of Egypt (= Pelican Books. Volume 168). 3rd edition, Viking, Harmondsworth 1985, ISBN 0-670-80153-4 .

- Mark Lehner : The Secret of the Pyramids in Egypt. Orbis, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , p. 95.

- V. Maragioglio, CA Rinaldi: L'Architettura delle Piramidi Menfite. Volume II, Artale, Turin / Canessa, Rapallo 1963.

- Frank Müller-Römer : The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt. Utz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , pp. 149–150.

- Ian Shaw (Ed.): The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, London 2000, ISBN 0-19-815034-2 .

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 75-77.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 174-177.

Web links

- ULB hall: Karl Richard Lepsius: Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia . On: edoc3.bibliothek.uni-halle.de Version from 10/2004; last accessed on April 18, 2014.

- Mark Lehner: Z500 and The Layer Pyramid ofZawiyet el-Aryan (en) ( Memento from October 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- Alexandre Barsanti: Ouverture de la pyramide de Zaouiet el-Aryan . On: gallica.bnf.fr ; last accessed on April 18, 2014.

- GA Reisner, CS Fisher: The Work of the Harvard University - Museum of Fine Arts Egyptian Expedition (pyramid of Zawiyet el-Aryan). In: Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin. December 1911, Volume IX, No. 54, Boston 1911 ( PDF file, online version ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rainer Stadelmann: King Huni: His Monuments and His Place in the History of the Old Kingdom. In: Zahi A. Hawass, Janet Richards (Eds.): The Archeology and Art of Ancient Egypt. Essays in Honor of David B. O'Connor. Volume II, Conceil Suprême des Antiquités de l'Égypte, Cairo 2007, pp. 425–431 ( online + PDF download ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Wiesbaden 1999, pp. 174-177.

- ^ Karl Richard Lepsius: Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia. Text 1, p. 128, Pyramid No. XIV , ( online version ).

- ↑ Alessandro Barsanti: Overture de la pyramide de Zaouiet el-Aryan. In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Volume 2, 1902, pp. 92-94 ( online version ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k G. A. Reisner, CS Fisher: The Work of the Harvard University - Museum of Fine Arts Egyptian Expedition (pyramid of Zawiyet el-Aryan). In: Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts (BMFA). Volume 9, No. 54, Boston 1911, pp. 54-59 ( online version with PDF download ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Mark Lehner: Z500 and The Layer Pyramid of Zawiyet-el-Aryan. ( Online version ).

- ^ V. Maragioglio, CA Rinaldi, L'Architettura delle Piramidi Menfite. Volume II, Turin / Rapallo 1963, p. 41ff.

- ^ Jean-Philippe Lauer: Histoire monumentale des pyramides d'Égypte. Volume 1: Les pyramides à degrés (IIIe Dynasty) (= Bibliothèque d'étude. Volume 39). Institut français d'archéologie orientale - Bibliothèque d'études, Paris 1962, pp. 19–22.

- ↑ JP Lauer: Histoire Monumentale des Pyramides d'Egypte. Volume I: Les Pyramides á Degrés. Pl. 27, Cairo 1962.

- ^ V. Maragioglio, C. Rinaldi: L'architettura delle Piramidi Menfite. Volume II. Rapallo, Naples 1963, pp. 41-49.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson: The Layer Pyramid of Zawiyet El-Aryan Its Layout and Context . In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. (JARCE) Volume 37, 2000, pp. 81-90 ( online version ).

- ↑ Dows Dunham: Zawiyet el-Aryan: the cemeteries adjacent to the Layer Pyramid. Dept. of Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1678, ISBN 978-0-87846-119-6 .

Coordinates: 29 ° 55 ′ 58 ″ N , 31 ° 9 ′ 40 ″ E