Red pyramid

| Red pyramid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The red pyramid of Sneferu

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

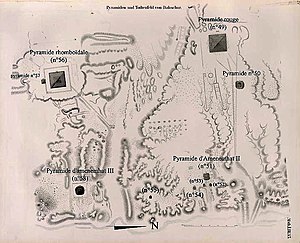

The Red Pyramid , also known as the North Pyramid is the largest of the pyramids in the necropolis of Dahshur .

It owes the name Red Pyramid to the reddish color of the rock from which its core, which is now uncovered, was built. It is about as high and almost as old as the bent pyramid two kilometers to the south . After this south pyramid, the north pyramid of Dahshur was the third great pyramid that was built for King Sneferu ( Pharaoh from about 2670 to 2620 BC) during the 4th Dynasty in the Old Kingdom and was probably used as a tomb. It was the first time that a real geometric pyramid, which was planned as such from the start, was completed. The Red Pyramid is the third largest of the ancient Egyptian pyramids and exceeds the basic measure even the Pyramid of Chephren .

exploration

Pietro della Valle provided the first description of the first two chambers of the pyramid when he visited the pyramid in the winter of 1615/1616. Edward Melton visited the red pyramid in 1660, as did the Bohemian Franciscan missionary Václav Remedius Prutký in the 18th century. Robert Wood , James Dawkins, and Giovanni Battista Borra conducted an initial survey in 1750 but were unable to reach the burial chamber because they did not have a suitable ladder.

At the beginning of the archaeological research of the Red Pyramid were the investigations of John Shae Perring in 1839 and the Prussian Lepsius expedition in 1843. Richard Lepsius cataloged the pyramid under the number XLIX (49) in his list of pyramids . This was followed by studies by Flinders Petrie and George Reisner . From 1944 onwards, more detailed research was carried out by Abdulsalam Hussein and from 1951 by Ahmed Fakhry . However, this work was not published. A thorough, systematic investigation was not carried out until 1982 by Rainer Stadelmann .

The pyramid complex was in a restricted military area until the mid-1990s and is currently the site of several excavations. A workers' settlement of the builders and a necropolis were found in the district .

Assignment of the pyramid

The assignment to Sneferu originally resulted from the fact that the nearby necropolis only includes graves of officials under Sneferu. Furthermore, a decree by King Pepi I , which was found in the valley temple, refers to the pyramid city of Snofrus. This assignment could be confirmed, since cladding stones were found in the area of the mortuary temple with inscriptions, including the king's name Snofrus. There was also a limestone block with hieroglyphic remains , which can be added to the Horus name Snofrus, "Neb-maat" (nb-m3ˁ.t) .

Construction circumstances of the pyramid

The construction of the pyramid probably began in the 29th or 30th year of Sneferu's reign (around 2640 BC). This is supported by a hieratic inscription on one of the foundation blocks, which refers to the year of the 15th cattle count, which was probably carried out every two years under Sneferu. The latest found inscription of the construction time refers to the 24th year of the cattle census. It was the third great pyramid that was built for this pharaoh. When construction began, the step pyramid in Meidum had already been completed as an eight-step pyramid. The bent pyramid was also largely completed in Dahshur , but it showed serious structural defects that made its use as a royal grave undesirable.

Apparently, the first construction work for another large pyramid in Dahshur began when the bent pyramid was still being built next to it; At the same time, the step pyramid was expanded in Meidum into a smooth, uneven surface. The problems that arose during the construction of the bent pyramid were taken into account in several ways in the new building project. For example, a building site further north with a more stable subsurface was chosen, a structure with a flatter angle of inclination was planned and the structure was designed with adapted masonry technology so that no more problems with cracks in the masonry occurred. In addition, there was no underground corridor system.

The pyramid

The pyramid rests on a foundation made of several layers of high-quality Tura limestone. The core of the pyramid, on the other hand, consists of reddish limestone blocks that were extracted from quarries in the immediate vicinity of the pyramid. The current name of the Red Pyramid comes from the coloring of this material. Inscriptions with dates were found on several blocks of the built-up material.

A foundation block is dated to the "year of the 15th cattle count", the most recent inscription to the "year of the 24th cattle count". Based on the information found, one can conclude - provided that the cattle census took place every two years - that around a fifth of the pyramid was built within two years. However, the two-year cycle of the livestock census is not without controversy.

The pyramid was built using the improved techniques used on the top of the bent pyramid. The stone layers were now horizontal from the beginning, so that the pressure inside the pyramid, which had led to cracks and the risk of collapse for the chambers inside the kink pyramid, was not increased. As for the upper side surfaces, the angle of inclination has now been set to less than 44 °. John Perring gives it as 43 ° 36 '11 ", based on the remaining stones of the cladding, with a base dimension of the equivalent of 219.3 m and a height of 104.4 m. This angle determined by Perring corresponds to an ancient Egyptian angle of 7.35 secs , i.e. a tangent of 7 / 7.35 (= 20/21). With this angle of inclination, a height comparable to the bent pyramid of around 105 m (200 royal cells) could be achieved by significantly increasing the base length to around 220 m (420 royal cells). The side surfaces of the pyramid core have a slightly concave kink that runs upwards from the center of the base. This should possibly improve the stability of the cladding attached to it. In contrast to the previous buildings, the pyramid was completed without any changes to the plan.

The pyramidion

In the rubble of Dahshur in front of the east side of the pyramid, R. Stadelmann discovered the fragments of a pyramidion in 1982 , which is considered the oldest of all those found so far and, like only two others, is assigned to a pyramid of the 4th dynasty of the Old Kingdom. The reassembled and restored pyramidion is now placed in the area of the mortuary temple in front of the Red Pyramid and, like the cladding of the pyramid, is made of fine Tura limestone. It was made from a monolithic block and measures 3 royal cells (about 1.57 m) at its base, the inclination angle of the sides is about 54 °, which is not exactly the same. This pyramidion is steeper than the remaining remains of the Red Pyramid or the upper part of the neighboring older bent pyramid (around 43 °) and about as steep as its lower part. There are neither inscriptions on the stone nor references to the attachment of metal sheets which, according to a report by Herodotus , are said to have been at the tips of the pyramids.

The substructure

All corridors and chambers of the Red Pyramid are located above the pyramid base in the brick core. It is the first and only pyramid that does not have any underground passages. The reason may lie in the king's increasing identification with the sun god Re, however, for purely practical reasons, an acceleration of the work on the pyramid by dispensing with underground components is conceivable. Although the chambers are above ground, they are built on a shallow excavation about 10 m deep.

The entrance to the pyramid is on the north wall at a height of 28 m and is shifted 4 m from the central axis to the east. The descending corridor leads 62.63 m at an angle of 27 ° down to the base of the pyramid. This corridor is only 0.91 m high and 1.23 m wide. At the foot of the descending corridor there is a short shaft that was presumably intended to prevent rainwater from entering the chambers during construction. From there a short horizontal passage leads into the first antechamber. Fall stone barriers are not available.

The two antechambers have identical dimensions. With a length of 8.36 m and a width of 3.65 m, the eleven-step cantilevered vaulted ceiling rises to a height of 12.31 m. In terms of design and visual effect, it is the forerunner of the great gallery of the Great Pyramid of Cheops . From the southwest corner of the first antechamber a 3 m long corridor leads to the northeast corner of the second antechamber, which is located exactly in the middle of the pyramid. At a height of 7.6 m on the south side of the chamber there is the entrance to another 7 m long corridor that leads to the actual burial chamber. The wooden staircase in the second antechamber is a modern construction to enable visitors to enter the burial chamber.

The actual burial chamber has the dimensions 8.55 m × 4.18 m with a height of 14.67 m. In contrast to the two antechambers, it is oriented in an east-west direction, which was an innovation in the pyramid construction. No remains of a sarcophagus have been found. The chamber itself has been badly damaged by grave robbers who tore out several layers of the floor stones. The ceiling and walls are blackened with soot , which may be due to torches and a possible burning of the wooden sarcophagus by the grave robbers. When it was reopened by Perring , the chamber was partially walled up with limestone, which probably came from a restoration of the Ramesside period . When the chamber was cleared by Hussein in 1950 , both the masonry stones and loose stones from the flooring were removed and lost without documentation. Follow-up examinations by Stadelmann could no longer provide any information on the remains of the original chamber contents.

The pyramid complex

In contrast to the other pyramids of the 4th Dynasty, the Red Pyramid does not have a cult pyramid . This element may have been left out, as the nearby bent pyramid had taken over its function as a symbolic south tomb.

Remains of the access road have not yet been found, although one was certainly planned between the valley and mortuary temple. However, this may not have been completed or even started.

A larger brick building was found southeast of the complex, which apparently housed workshops. The remains of an oven were also found there.

The enclosing wall

During excavations by Stadelmann, the remains of an adobe building were found at the northeast corner of the pyramid , which was directly adjacent to a wall also made of adobe bricks. The exact purpose of the building has not yet been determined, but a connection with the ruler's cult is obvious.

Further exploratory excavations were able to prove the surrounding wall around the pyramid. Part of the wall was clad in limestone. The distance between the wall and the pyramid is different on the four sides: 15 to 16 m on the north and south side, 19 m on the west side and 26 m on the east side. In contrast to the wall of the bent pyramid, it is not square, but slightly east-west.

Stadelmann interprets the fact that the wall was built from adobe rather than limestone as in the Bent Pyramid as an indication that it was apparently built in a hurry to complete the complex. The northeast building was apparently a later addition, as the walls were not jointed with the surrounding wall.

The mortuary temple

The mortuary temple was largely destroyed and is only preserved in the form of a few rudimentary ruins. It is not yet the size of the mortuary temples of later pyramids. In the center of the temple there was a sacrificial site with a false door in the inner temple . Steles like those of the older Sneferu pyramids are not detectable here. There was a stone chapel on either side of the open courtyard. It can no longer be determined whether these chapels were free-standing buildings or were integrated with the courtyard and the inner temple to form a building complex. The courtyards to the north and south of the temple have circular depressions, which probably once served as plant pits or to hold offerings. The magazine rooms in the outer area of the temple were made of adobe bricks. Apparently the mortuary temple was not completed in a hurry until after Snofru's death, which is indicated by the change in the building material from limestone to mud brick.

The valley temple

During agricultural work in the spring of 1904, the remains of a limestone enclosure wall measuring 100 m × 65 m were discovered. At the southeast corner of the walls there was a stele with a decree by Pharaoh Pepi I. Ludwig Borchardt , who secured the stele, believed this find to be the surrounding wall of the pyramid city. Stadelmann sees it as the enclosure of the valley temple, as the walls of the pyramid cities (with the exception of Gizeh) were made of adobe bricks. The found wall, 3.65 m thick, made of yellow limestone and white facing sloping on both sides, corresponds in its execution to the typical sacral architecture . However, no further systematic investigation was carried out and the remains are now inaccessible under agricultural land.

Open questions

The Red Pyramid is generally considered to be the most likely burial place of Snofru, but this cannot be clarified with certainty, as no stone sarcophagus could be detected in any of the three large pyramids attributed to Snefru. If the red pyramid was the tomb, it is also still unclear why there were no locking mechanisms installed there, as existed in front of the upper chamber of the bent pyramid.

The mummy remains found in the Red Pyramid in the 1950s could not be reliably assigned to Sneferu and most likely came from a subsequent funeral that was not related to Sneferu.

meaning

With the red pyramid, the high phase of pyramid construction of the 4th dynasty was reached. The necessary techniques had been developed and the problems that arose mastered, so that the way to the construction of the Great Pyramid was clear. While the red pyramid had an overcautiously flat angle of inclination, the following pyramids again had a greater slope.

Literature / sources

General overview

- IES Edwards : Dahshur, the Northern Stone Pyramid. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 215-16.

- Michael Haase : The field of tears. Ullstein, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-550-07141-8 .

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Econ, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-572-01039-X .

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 .

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 .

Questions of detail

- Rainer Stadelmann: Sneferu and the pyramids of Meidum and Dahschur. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDAIK) Vol. 36, 1980, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 437–449.

- Rainer Stadelmann: The pyramids of Sneferu in Dahschur. Second report on the excavations on the northern stone pyramid with an excursus about false doors or steles in the mortuary temple of the AR. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department, Vol. 39, 1983, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 225–241.

- Rainer Stadelmann, Nicole Alexanian, Herbert Ernst, Günter Heindl, Dietrich Raue: Pyramids and necropolis of Sneferu in Dahschur. Third preliminary report on the excavations of the German Archaeological Institute in Dahschur. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department, Vol. 49, 1993, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 259–294.

- Rainer Stadelmann, Hourig Sourouzian: The pyramids of Snefru in Dahschur. First report of the excavations on the northern stone pyramid. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department, Vol. 38, 1982, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 279–393.

Individual evidence

- ^ Roman Gundacker: On the structure of the pyramid names of the 4th dynasty. In: Sokar No. 18, 2009, pp. 26-30.

- ↑ The spelling with the addition "North" has only been documented since the Middle Kingdom.

- ↑ a b c years after Thomas Schneider : Lexikon der Pharaonen . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 .

- ^ A b c John Shae Perring , Richard Howard-Vyse, William Howard: Operations carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837: with an account of a voyage into upper Egypt, and Appendix. Volume 3 Appendix. Fraser, London 1842, p. 65; Digitized version of the University of Heidelberg online .

- ↑ IES Edwards : Dahshur, The Northern Stone Pyramid. In: Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. ed. by Kathryn A. Bard, New York 1999, pp. 215-216.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 978-3-498-07062-5 , p. 212 ff. The Red Pyramid of Snefru .

- ↑ Vito Maragioglio , Celeste Rinaldi : L 'Architettura delle Piramidi Menfite. Vol. III: La piramide di Meydum e le piramidi di Snefru a Dahsciur Nord e Dahsciur Sud. Rapallo, Turin 1964, p. 124.

- ↑ a b Ludwig Borchardt : A royal decree from Dahschur. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. No. 42, 1905, pp. 1-11.

- ↑ Hans Goedicke : Royal documents from the Old Kingdom (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen Vol. 14). Wiesbaden 1967, pp. 55-77 and Fig. 5.

- ↑ a b Rainer Stadelmann, Nicole Alexanian, Herbert Ernst, Günter Heindl, Dietrich Raue: Pyramids and necropolis of Snefru in Dahschur. Third preliminary report on the excavations of the German Archaeological Institute in Dahschur. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department, Vol. 49, 1993, pp. 259–294.

- ↑ Rainer Stadelmann: The pyramids of Snefru in Dahschur. Second report on the excavations on the northern stone pyramid with an excursus about false doors or steles in the mortuary temple of the AR. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologische Institut, Kairo Department, Vol. 39, 1983, p. 233, Fig. 5, Plate 73d.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. Mainz 1997, pp. 99-105

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Mark Lehner: Mystery of the pyramids. Econ, Düsseldorf 1997, p. 104 ff. The north pyramid .

- ^ Corinna Rossi: Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1-107-32051-2 , pp. 207f .

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. Mainz 1997, p. 98.

- ↑ Rainer Stadelmann: The pyramids of Snefru in Dahschur. Second report on the excavations on the northern stone pyramid with an excursus about false doors or steles in the mortuary temple of the AR. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department, Vol. 39, 1983, pp. 225–241.

- ↑ Renate Germer: Remains of royal mummies from the pyramids of the Old Kingdom - do they really exist? In: Sokar No. 7, 2003, pp. 37-38.

Web links

- The Red Pyramid of King Sneferu in Dahshur-North

- The Red Pyramid (Engl.)

- Alan Winston: The Pyramid of Snefru (Red Pyramid) at Dahshur (engl.)

| before | Tallest building in the world | after that |

| Bent pyramid of Sneferu | (105 m) around 2600 BC BC - around 2570 BC Chr. |

Cheops pyramid |

Coordinates: 29 ° 48 ′ 31 ″ N , 31 ° 12 ′ 22 ″ E