Alexander Issayevich Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn [ səlʐɨnʲitsɨn ] ( Russian Александр Исаевич Солженицын ., Scientific transliteration Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Isaevič * 11. December 1918 in Kislovodsk , Terek Oblast , † 3. August 2008 in Moscow ) was a Russian writer and critics of the system . He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970. His main literary work The Gulag Archipelago describes in detail the crimes of the Stalinist regime in the exile and systematic murder of millions of people in the Gulag .

Life

Alexander Solzhenitsyn's father, a Cossack, died before Alexander was born. Since his mother was very ill, he grew up mainly with his grandparents. With them he was made familiar with the faith as well as the Russian customs and traditions. In 1924 his mother moved to Rostov-on-Don , where he also attended school. At the age of nine he already had the desire to become a writer. He graduated from high school in 1936 and subsequently took up studies in the fields of mathematics and physics in Rostov-on-Don. He actually wanted to study literature in Moscow, but the financial means were insufficient. In his youth he was enthusiastic about the views and political orientations of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (→ Leninism ). This resulted in numerous approaches and evaluations of his later confrontation with Stalinism. On April 7, 1940, he married the chemist Natalja Alexejewna Reshetovskaya. A year later he was drafted for military service in the Red Army .

In the German-Soviet war Solzhenitsyn fought as a battery chief of an artillery unit in a sound measuring force . In this capacity he took part in the Battle of Kursk (July 1943), Operation Bagration (1944) and the Vistula-Oder Operation in East Prussia (1945). He wrote down his experiences as an officer during the conquest of East Prussia in poetry in the volume Ostpreußische Nights (Прусские ночи) and as a story in Schwenkitten '45 (Адлиг Швенкиттен). As a captain, he was awarded the Order of the Great Patriotic War and the Order of the Red Star for his services .

Survival in the Gulag and exile

In February 1945, Alexander Solzhenitsyn was surprising at the front by the military counterintelligence arrested and taken to Moscow's Lubyanka transferred -Gefängnis because it in letters to a friend criticizing Stalin had practiced. In accordance with Article 58 of the Soviet Criminal Code, he was sentenced to eight years' imprisonment and subsequent “perpetual exile ” without a trial . He was detained in the Gulag labor camps . First he was placed in a special camp for scientists, where he met Lev Kopelev, who was also imprisoned . He processed his experiences with this special camp in 1968 in the novel The First Circle of Hell (В круге первом). Since he refused to fulfill the work requirement to deal with given scientific topics, Solzhenitsyn was later transferred to the Ekibastus camp complex in Kazakhstan for political prisoners. In this camp he worked in a foundry.

Both in the special camp at the beginning of his captivity and in the Ekibastus camp, he experienced the struggle of the camp inmates for survival and faced the constant threat of hunger, riots and unattainable labor standards. Prisoners kept dying near him. Solzhenitsyn, the former atheist and supporter of communism, also described in his novel his own spiritual development through the sufferings and experiences during this time. He later made a strong commitment to Orthodox Christianity .

In 1952, a year before his release from the Gulag, Solzhenitsyn's wife Natalja ("Natascha") divorced him. This was initially done by mutual agreement in order to avoid further reprisals from the Stalinist power apparatus, since a marriage to a political prisoner could have led to dismissals or persecution. According to her own statement, Natascha remained loyal to her husband during the first years of his imprisonment from 1945 to 1950, and “a feeling of great inner connection” even seemed to deepen, although during this time they often only saw each other a few times a year. Then Natascha turned away from him and let the new assistant professor at her institute, Vsevolod Somow, who already had a son, move in with her. Solzhenitsyn received the message from his aunt in the camp: "Natascha asked me to tell you that you can organize your life independently of her."

In 1951 Solzhenitsyn was diagnosed with cancer. This was one of the reasons why Natascha only let her aunt inform him of the separation later. The cancer was operated on in the camp hospital and there was hope that no further metastases had formed.

In February 1953 Solzhenitsyn was released from the camp and began to be exiled. The village of Berlik in the Kok-Terek district in the steppe of Kazakhstan was assigned to him as a place of exile . Shortly after his arrival there, he learned of Stalin's death on March 5, 1953. Despite his joy, he kept a low profile and just started looking for better accommodation after this “wonderful present”, as Donald Thomas calls it in his biography about Solzhenitsyn . After initially unable to find a job as a political prisoner, he finally got a job as a village school teacher specializing in mathematics, physics and astronomy.

“I - in a class, chalk in hand! That was it, the day of my liberation, of my re-establishment of citizenship. I didn't notice anything else that belonged to the exile. "

In December 1953, he had to undergo medical treatment again for a tumor the size of a fist in the abdominal cavity, this time in a Tashkent hospital, where he was last irradiated in 1955 . The chance of survival was initially less than 30%. He later processed the experience of this treatment in the novel Cancer Ward (Раковый корпус).

Life in the Soviet Union after exile

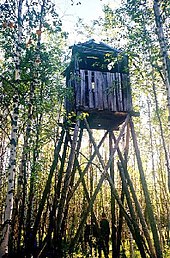

In 1957, during the thaw , Solzhenitsyn was officially rehabilitated and the exile was lifted. Given his cancer, he could be expected to die soon. He then lived in Ryazan , where he worked as a teacher at the regional high school. The time was marked by the rapprochement with Natascha, whom he remarried in 1957, and by great zeal for work. He saw it as his task to lend his voice to those who had been silenced. He often retired to huts away from civilization so that he could write undisturbed. Natascha supported him personally and financially and enabled him to reduce his teaching obligations in favor of his literary work.

In 1962 he wrote one of his most famous works, the novella A Day in the Life of Iwan Denissowitsch (Один день Ивана Денисовича) about the cruel daily life of a prisoner in a Soviet labor camp and an examination of the Stalinist system. During this time he began to work full-time as a writer. In September 1962, several artists were invited to Khrushchev's dacha on the Black Sea. On this occasion Khrushchev got to know the story about Ivan Denisovich and one year later he allowed the publication of the book "August 14". That was the beginning of a multi-volume work on the history of Russia during the First World War . As a delegate at the 4th Writers' Congress in 1967, he launched a “call for the abolition of censorship”. In 1969 Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Writers' Union of the USSR on the grounds that he had published abroad without permission . In the following years he worked on the subject of the “GULAG Archipelago”. At the end of the 1960s he was generously welcomed into his dacha by his friend, the famous cellist Rostropovich . Rostropovich, who tried to defend Solzhenitsyn through open letters to newspapers such as Pravda , eventually fell out of favor himself and had to leave the Soviet Union in 1974.

In 1971 a KGB agent secretly poisoned Solzhenitsyn with a ricin gel. This caused a serious illness that was later identified as a result of the attempted murder.

In 1972 Solzhenitsyn and his first wife Natasha divorced. In 1973 he married Natalja Dmitrijewna Swetlowa (* 1939), a mathematician who had a son from a previous marriage. The couple had three sons: Jermolai (* 1970), Ignat (* 1972) and Stepan (* 1973).

Even before the publication of Volume I “The GULAG Archipelago”, the KGB obtained a copy of the manuscript through a confidante in its work environment. In this monumental main work The Archipelago Gulag (Архипелаг ГУЛАГ) Solzhenitsyn described the Soviet camp system ( Gulag ). The historical-literary work was published under time pressure in Tamizdat . Shortly afterwards, on February 13, 1974, he was arrested. While he was still in prison, he was presented with the "charges under Paragraph 64" (treason), and the next day he was expelled from the Soviet Union and immediately flown to Frankfurt am Main . The “confidante” committed suicide in view of the consequences of her actions.

Exile and homecoming

Solzhenitsyn initially found acceptance in the Federal Republic of Germany with Heinrich Böll ; later he lived in Sternenberg in the holiday home of the mayor of Zurich, Sigmund Widmer, in Switzerland. Volume II of "Archipel GULAG" was also published during this time. It followed in 1975 "The Oak and the Calf" and "Three Speeches to the Americans". In 1976 the family moved to the USA. The III. Volume "The GULAG Archipelago" and "East Prussian Nights". At that time he was already living in Cavendish in Vermont . In 1980 the books “The Deadly Danger / Warning of Communism” and “November sixteen”, the 2nd volume of “The Red Wheel”, were published. After taking office in March 1985, Michael Gorbachev initiated glasnost and perestroika . Andrei Sakharov was rehabilitated at the end of 1986, along with other members of the opposition from the time of the Stalinist purges (partly posthumously) in 1987. In 1989 Solzhenitsyn was re-admitted to the Soviet Writers' Union. In the same year his book “March seventeen” was published - the third volume of “Das Rote Rad”.

In 1990 Solzhenitsyn was rehabilitated and regained his Soviet citizenship . His book “Russia's Way Out of the Crisis. A manifest ”. In 1991 the pending charges against him were overturned; in the same year the Soviet Union disintegrated . Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia on May 27, 1994. More and more clearly he now became a proponent of the Russian politics of the time and a leading figure of the nationally thinking forces of Russia. In the same year he published “Progress at Any Price” and the book “The Russian Question at the End of the 20th Century”. To give him better opportunities to express his views in public, he was offered his own television magazine on Russian television. The program was taken off the program shortly before the general election on December 17, 1995 and due to its dwindling popularity. In the same year his book “Heldenleben. Two stories ”and he had the opportunity to address the Russian parliament . In 1997 he was admitted to the Russian Academy of Sciences .

Forty years after the publication of his first novella A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich , Solzhenitsyn positioned himself in his national epic Two Hundred Years Together (Двести лет вместе), which was published between 2002 and 2004, as an arch-conservative, intolerant interpreter of history on the Russian-Jewish question , who was ready to to work with anti-Semitic enemy images . In this late work he clearly offered ammunition for the abuse of his humanistic positions of the earlier creative years.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn died on August 3, 2008 at 11:45 p.m. Moscow time at the age of 89 in his Moscow home and with his family as a result of a stroke . He left his widow and three sons. The funeral took place on August 6, 2008 in Moscow's Donskoy Monastery .

Political activity

Although he was very welcome abroad and his privacy was respected, Russia always remained his spiritual home. His work Between Two Millstones (Угодило зернышко промеж двух жерновов) testifies to how much he felt taken by "some circles" (see also Nikolai Getman ). Always convinced that one day he would return to his homeland, he made no effort, for example, to learn the English language and to feel at home in the United States.

After his return to the former Soviet Union in 1994, however, he was soon disappointed by the conditions there, since in his eyes his homeland was further than ever from the “moral renewal” he had dreamed of. In 1999 he criticized NATO's mission in Yugoslavia on several occasions : “A great European country is in the process of being destroyed under the eyes of mankind, and civilized governments applaud [...] After they threw the United Nations on the trash, the United Nations proclaimed NATO has an old law for the world for the coming century - that of the jungle: The strongest is always right. ”He called on Boris Yeltsin to withdraw from Chechnya during the first Chechen War . However , he had no objection to the second war in Chechnya that Vladimir Putin had started and even called for the death penalty for “Chechen terrorists” in this context. Finally, he even met with Putin for a conversation in which both of them talked about the fate and size of Russia.

Solzhenitsyn rejected the developments in Russia, especially under Yeltsin, which is why he also rejected the state awards he was offering. Gorbachev seemed to him politically naive, inexperienced and irresponsible: “That was not an exercise of power, but a senseless renunciation of power. He felt that this behavior was confirmed by the enthusiasm of the West. ”In his opinion, Boris Yeltsin was primarily responsible for the desolate state of Russia, which he described in his book Russia in the Crash . The privatization carried out under his dictation led to the "unrestrained robbery of Russian wealth". Yeltsin also promoted separatist tendencies and “had resolutions passed that were supposed to tear the Russian state to pieces. This deprived Russia of its well-deserved historical role and position on the international stage. What was acknowledged by the West with loud applause. "

Solzhenitsyn saw the US influence as disastrous and criticized its cynical pragmatism, which had contributed to the loss of confidence in democratic ideals. He mentions the bombing of Belgrade as a special event that had a lasting impact on Russia.

He was particularly concerned about the dissolution of ties between Russia, the Russians outside Russian borders, and the countries previously associated with Russia, particularly Ukraine. He saw here a damaging influence of the West, which had its roots in the unwillingness and ability to perceive the difference between Russia and the Soviet Union. “In addition, there were attempts by NATO to pull parts of the collapsed USSR into its sphere, above all - which was particularly painful - Ukraine, a country closely related to us, with which we are connected by millions of family relationships. These could be cut in no time by a military alliance border. "

reception

A history of reception in the Federal Republic of Germany, Great Britain and the USA is described in the book Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Cold War Icon, Gulag Author, Russian Nationalist? A Study of the Western Reception of his Literary Writings, Historical Interpretations, and Political Ideas (Stuttgart, 2014) critically analyzed by the comparator Elisa Kriza.

Since 2006, the Moscow publishing house Vremja ("Time") has published a 30-volume edition of his complete works. In September 2012, 16 volumes of this edition were completed. The main work Archipel GULAG was published in volumes 4 to 6 of the series.

For his two-volume late work Two Hundred Years Together (Двести лет вместе), which is supposed to record Jewish- Russian history from 1795 to 1916 (Volume 1) and from 1917 to 1972 (Volume 2), Solzhenitsyn reaped harshly in his own and also in Western countries Criticism as it contains several approaches that can be interpreted as anti-Semitic . The main reason for this was that he deduced from historical developments that Russians and Jews had to share responsibility for the terror regime in the early phase of the Soviet Union , which is why he calls on both sides to "repent". It was also offended by the fact that he contradicts the current account that, for example, the pogroms in Kishinev had been prepared and initiated by the Russian authorities. Instead, Solzhenitsyn explains them with incompetence and perplexity on the part of the police and laments the “flaming exaggerations” with which “ tsarism ” has been turned into an object of hate and a horror in the western liberal public. Even in a pogrom of 1882, Solzhenitsyn downplayed the number of victims, contrary to the research results. In addition, his selective way of quoting was criticized as well as the fact that he had hardly used Western research literature.

Awards

- 1969: Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1969: Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1970: Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1983: Templeton Prize

- 1998: Lomonosov Gold Medal of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- 2007: State Prize of the Russian Federation by President Putin

- 2008: Grand Cross of the Star of Romania (posthumous)

References to Solzhenitsyn

- Under the impression of Solzhenitsyn's Gulag archipelago , the former left-wing radical André Glucksmann analyzed in his book Cook and Ogre - On the Relationship between State, Marxism and Concentration Camps Marxism-Leninism and Stalinism and relentlessly reckoned with the crimes of the Soviet Union. This had a great influence on the Western European left (see also Nouvelle Philosophy ).

- In his novel Der Gaukler (1978), the GDR writer Harry Thürk refers clearly to Solzhenitsyn - even if his name is not mentioned directly - and portrays him as a morally depraved, counterrevolutionary Soviet writer in the service of Western secret services the official view of the GDR on Solzhenitsyn served.

Fonts

- A day in the life of Ivan Denisovich. Published 1962

- Matrjonas Hof published in 1963

- The first Circle of Hell manuscript was smuggled abroad and published there in 1968

- Cancer ward . 2 volumes. Neuwied 1967–1969.

- Nobel Prize Speech 1970

-

Das Rote Rad - first volume 1971 / year of publication 1986 in closed form of the first volumes

- August fourteen, published in 1971 ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from September 18 to October 1, 1972 )

- November sixteen year of publication 1980 as volume 2 of Das Rote Rad

- March seventeen year of publication 1989, as volume 3

- April seventeen (not translated) with no year of publication - actually Volume 4, but Solzhenitsyn stopped this work for reasons of age

- Incident at Kretschetowka station , stories. dtv, Munich 1972 ISBN 3-423-00857-1 .

-

The Gulag archipelago

- Volume I. Year of publication 1973 ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from February 18 to November 17, 1974 )

- Volume II. Year of publication 1974 ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from November 18, 1974 to March 30, 1975 )

- Volume III. Year of publication 1976

- Lenin in Zurich (1975)

- Voices from the Underground (Essays on the Past and Future of Russia) Published in 1975

- The oak and the calf. Sketches from literary life published in 1975

- Three Speeches to Americans Published 1975

- East Prussian Nights . A poem in verse , Russian-German, translated by Nikolaus Ehlert, Luchterhand, Darmstadt and Neuwied, published in 1976

- Candle in the Wind was published in 1977

- Republic of Labor, published 1977

- The Deadly Peril / Warning of Communism Published 1980

- Russia's way out of the crisis. A manifesto published in 1990

- The Russian Question at the end of the 20th century published in 1994

- Progress at Any Price Year of publication 1994

- Heldenleben - Zwei Erzählungen Published in 1995

- Russland im Umbruch, published 1998

- Nemow und das Flittchen (play) with no year of publication

-

Two Hundred Years Together (on the coexistence of Jews and Russians in Russia and the role of Jews in recent Russian history) year of publication 2002

- Volume 1 - The Russian-Jewish History 1795–1917 - published in 2003

- Volume 2 - The Jews in the Soviet Union - published in 2004

- Schwenkitten '45 published in 2004

- Between two millstones. My life in exile published in 2005

- What happens to the soul during the night? Year of publication 2006

- For the benefit of the matter, published in 2007

- My American Years Published in Russian 2004, German 2007

literature

The free Internet database RussGUS offers over 800 references to Solzhenitsyn / Solzenicyn.

- David Burg and George Feifer: Solzhenitsyn. Biography. Kindler, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-463-00498-4 .

- Pierre Daix: What I know about Solzhenitsyn. List, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-471-66547-1 .

- John F. Dunn: "One Day" from the standpoint of a lifetime. Ideal consistency as a design factor in the narrative work of Aleksandr Isaevic Solzenicyn. Sagner, Munich 1988, (= Slavic contributions; 232) ISBN 3-87690-415-3 .

- Rudi Dutschke, Manfred Wilke (ed.): The Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn and the western left. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1975 (= rororo; 1875; current), ISBN 3-499-11875-0 .

- Henning Falkenstein: Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Colloquium, Berlin 1975 (= heads of the 20th century; 79), ISBN 3-7678-0377-1 .

- Elisa Kriza: Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Cold War Icon, Gulag Author, Russian Nationalist? A Study of the Western Reception of his Literary Writings, Historical Interpretations, and Political Ideas. ibidem Verlag, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-8382-0589-2 .

- Reinhold Neumann-Hoditz: Alexander Solschenizyn in personal testimonies and photo documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1974 (= Rowohlt's monographs; 210; rororo picture monographs), ISBN 3-499-50210-0 .

- Andreas Korotkov (Ed.): Solzhenitsyn Files. 1965-1977. Secret documents of the Politburo of the CPSU and the KGB. With a letter from Alexander Solzhenitsyn as escort. Ed. q., Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-86124-249-4 .

- Anatoly Livry, “Soljénitsyne et la République régicide”, Les Lettres et Les Arts, Cahiers suisses de critique littéraire et artistiques, Association de la revue Les Lettres et les Arts, Suisse, Vicques, 2011, p. 70-72. http://anatoly-livry.e-monsite.com/medias/files/soljenitsine-livry-1.pdf

- Elisabeth Markstein (Ed.): About Solzhenitsyn. Articles, reports, materials. Luchterhand, Darmstadt u. a. 1973, ISBN 3-472-86275-0 .

- Werner Martin (Ed.): Alexander Solschenizyn. A bibliography of his works. Olms, Hildesheim u. a. 1977, ISBN 3-487-06429-4 .

- Roy Medvedev : Solzhenitsyn and the Soviet Left. An examination of the GULag archipelago and other writings. Olle et al. Wolter, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-921241-25-1 .

- Michael Martens: A shouter in many deserts (Alexander Solzhenitsyn is 80 years old today). In: Extra (weekend supplement to Wiener Zeitung), 11./12. December 1998, page 9.

- Mahesh Motiramani : The function of literary quotations and allusions in Aleksandr Solzenicyn's prose (1962–1968). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1983 (= European University Writings; Series 16, Slavic Languages and Literatures; 25), ISBN 3-8204-7812-4 .

- Donald M. Thomas: Solzhenitsyn. The biography. Propylaea, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-549-05611-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Alexander Issajewitsch Solschenizyn in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Alexander Issajewitsch Solschenizyn in the German Digital Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1970 award to Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn (English)

- Biography and background in the GULAG Memorial Project

items

- Juri Ginsburg: "The Controversial Patriarch" , Berliner Zeitung , December 6, 2003.

- Konstantin Asadowski: "What is Alexander Solzhenitsyn doing?" , In: Cicero 2004.

- “Written with the blood of millions” , Spiegel Online , July 23, 2007

- "27. May 1994: Alexander Solzhenitsyn returns to Russia ” , SWR2 Zeitwort, May 27, 2008, RTF file, 2 pages, 13.2 kB

- Hanns-Martin Wietek: Alexander Issajewitsch Solzhenitsyn: Don't live by lies , June 24, 2008

- “The Prophet in the Wheel of History” , FAZ , August 4, 2008, with article dossier, video, picture series

- "Solzhenitsyn, Literary Giant Who Defied Soviets, Dies at 89" , New York Times , August 4, 2008

- Obituary in The Economist August 7, 2008 English

- Hanns-Martin Wietek: The Unknown Solzhenitsyn , August 21, 2008

- Michael Hänel: Alexander Solzhenitsyn and his Gulag archipelago December 6, 2018 SWR2

Individual evidence

- ^ Victor Terras: Handbook of Russian Literature , Yale University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-300-04868-8 , p. 436.

- ↑ Donald M. Thomas: Solzhenitsyn. The biography. New York 1998, p. 260 ff.

- ↑ Donald M. Thomas: Solzhenitsyn. The biography. New York 1998, p. 273.

- ↑ Donald M. Thomas: Solzhenitsyn. The biography. New York 1998, p. 284 ff.

- ↑ The Gulag Archipelago, final volume , p. 430.

- ↑ Donald M. Thomas: Solzhenitsyn. The biography. New York 1998, p. 293 ff.

- ↑ Michael Scammell: Solzhenitsyn. A biography. London, Paladin 1986, ISBN 0-586-08538-6 , p. 366.

- ↑ https://www.br-klassik.de/aktuell/mstislaw-rostropowitsch-portraet-100.html

- ↑ Arkadii Vaksberg: Toxic Politics: The Secret History of the Kremlin's Poison Laboratory - from the Special Cabinet to the Death of Litvinenko . Praeger, Santa Barbara, Calif 2011, ISBN 978-0-313-38747-0 , pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Washington Post: Russia has a long history of eliminating 'enemies of the state' , accessed December 10, 2019

- ^ Bernard A. Cook: Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia . Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0-8153-4058-3 , p. 1161.

- ↑ David Aikman: Great Souls. Six Who Changed a Century. Lexington Books, 2003, ISBN 0-7391-0438-1 , p. 172 f.

- ↑ Cf. Die Eiche und das Kalb , Luchterhand 1975, p. 513.

- ↑ Alexander Solzhenitsyn turned eighty. An appreciation The calf and the oak , article from December 12, 1998 by Gerd Koenen ( berliner-zeitung.de )

- ^ Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences since 1724: Solzhenitsyn, Alexander Issajewitsch. Russian Academy of Sciences, accessed August 31, 2019 (Russian).

- ↑ Martina Neubert, The Two Faces of a Writer , Berliner Morgenpost, August 17, 2007

- ↑ Law of the Jungle. In: taz.de . April 12, 1999, accessed January 8, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Christian Neef and Matthias Schepp: "Written with blood" . In: Der Spiegel . No. 30 , 2007 ( online ).

- ↑ flf / AP: Russia: Writer Solzhenitsyn is dead. In: Focus Online . August 4, 2008, accessed January 8, 2017 .

- ^ Homepage of the Vremja publishing house , (accessed on September 20, 2012)

- ↑ Quotation from the review by Arno Lustiger in the Berliner Zeitung on October 7, 2003

- ↑ Quoting from the review by Ernst Nolte in Junge Freiheit on November 22, 2002

- ↑ Solzhenitsyn on the relationship between Russians and Jews: Difficult neighborhood. In: nzz.ch. August 10, 2001. Retrieved January 8, 2017 .

- ^ Review by Elfie Siegl, www.dradio.de, May 12, 2003

- ↑ Honorary Members: Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 23, 2019 .

- ^ American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Book of Members ( PDF ). Retrieved April 21, 2016.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Solzhenitsyn, Alexander Issajewitsch |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Солженицын, Александр Исаевич (Russian); Solženicyn, Aleksandr Isaevič (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian writer, playwright, historian and Nobel laureate in literature |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 11, 1918 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kislovodsk |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 3, 2008 |

| Place of death | Moscow |