The Gulag archipelago

Location: 65 ° 51 ′ N , 88 ° 4 ′ E (near the Arctic Circle , about an hour's flight east of Turuchansk )

The Gulag Archipelago (Original: Russian Архипелаг ГУЛАГ GULAG Archipelago ) is a historical-literary work by the Russian writer , dissident and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature Alexander Issayevich Solzhenitsyn . The Gulag archipelago, first published in France on December 28, 1973, is considered his main work and one of the most influential books of the 20th century. It is the best-known work of samizdat literature from the Stalin and Khrushchev era in the Soviet Union, which was often created and widespread underground, and the most significant representation and criticism of Stalinism in literature.

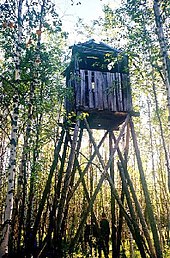

GULag or Gulag is a suitcase word for the Russian name Glawnoje Uprawlenije isprawitelno-trudowych Lagerei ( Russian Главное Управление Исправительно-трудовых Лагерей - Headquarters of the Umer Education and Labor Camps' ). The title of the book describes the camp system as an archipelago spread across the entire Soviet Union , a closed island world of oppression and dehumanization. This also takes up the title of the book The Island of Sakhalin by Chekhov , in which he described forced labor and exile under tsarism.

Publication history

Solzhenitsyn, interned in the Gulag from 1945 to 1953, worked on the Gulag Archipelago for over ten years from April 1958 , but withheld its publication and hid the manuscript. At that time he wrote the historical novel cycle Das Rote Rad , which he regarded as his most important work. A publication of the Gulag archipelago and the subsequent possible arrest would have made the work on it impossible, which he did not intend to complete until 1975.

Since September 1965 he was under constant observation by the KGB after his secret manuscripts for the novel The First Circle of Hell and the play Republic of Labor had come into their hands.

In 1970 Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature . He did not travel to Stockholm to receive the award, however, because he feared that the government would refuse him to re-enter the Soviet Union.

In August 1973, the KGB discovered parts of the manuscript on the Gulag archipelago . As a result, it no longer made sense for Solzhenitsyn to keep the work a secret. The Russian emigrant publisher YMCA-Press , which had a copy of the manuscript, was instructed by him to print the book immediately. It was published in Russian on December 28, 1973 in Paris. It was translated into German by Elisabeth Markstein under the pseudonym Anna Peturnig and was published a little later by Scherz Verlag and many other Western countries. It was not allowed to appear in the Soviet Union.

The original book contains Parts I and II ( The Prison Industry and Eternal Movement ). It later became a three-volume edition, which is divided into seven parts. Volume 2 and Volume 3 were published in 1975 and 1978, respectively. In 1985, an abridged, one-volume complete edition was published, which many consider to be easier to read.

It was first published in Russia in 1990. In 2009, at Vladimir Putin's request, it became school reading.

shape

After the publication of the short novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich , which was allowed to appear in the Soviet Union in 1962, many former camp inmates felt addressed and wanted to share their memories with Solzhenitsyn. More than two hundred people who were imprisoned between 1918 and 1956 wrote to him or sought a conversation. These testimonies are the basis of The Gulag Archipelago . In addition, there are Solzhenitsyn's own experiences and official public and secret documents and investigations. Solzhenitsyn wrote on the one hand as a faithful chronicler who faithfully reproduced the fate of the victims of Stalinism, on the other hand he also condensed their experiences literarily. The poetic structure becomes clear in the subtitle attempt at an artistic mastery . The attitude of the contemporary witness is emphasized in the preamble:

Dedicated to all those

who did not have enough life

to tell.

May you forgive

me for not seeing everything,

not reminding myself of everything,

not guessing everything.

That is why the Gulag archipelago sometimes looks like a non-fiction book , like a scientific paper with the appendix, like a list of biographical names and a list of abbreviations. There are also numerous “notes” in the footer of the pages. On the other hand, the book is a cynical political and literary manifesto , a pamphlet and an indictment of the judiciary and warehousing in the Soviet Union. At its core, it is dedicated to the victims, and sees itself as a reminder and appreciation of their lives and suffering.

content

In Part I, The Prison Industry, Solzhenitsyn describes the expansion and development of the Russian “prison industry” that has been going on since the Russian October Revolution . He compares the conditions in the judicial apparatus of the Soviet Union with those of the Tsarist era. He names the victims and perpetrators, whereby the “perpetrators” often only a few years later become “victims” of the system and end up in the archipelago themselves with the next wave of arrests. Solzhenitsyn writes that it was often not the crime (or suspicion) that was decisive for the arrest, but economic considerations and the need for labor. For him, the main culprit - Solzhenitsyn leaves no doubt - is Stalin. Admittedly, the atrocities of the revolutionary era and the Russian civil war for which Lenin is responsible draw a direct line towards Stalin.

Part II Eternal Movement deals with the “settlement” of the newly created archipelago by the “streams of prisoners” that flow from 1917 until the time the book was written through remand prisons and nationwide prisoner transports to the penal camps.

Part III deals with labor and extermination . Solzhenitsyn describes the world of the camp and describes the prisoners' journey from admission to death due to malnutrition, exhaustion, illness or due to sadistic guards. It describes the representative (but sometimes wrongly planned or practically useless) buildings of the Stalin era and the life and work of the prisoners involved. Solzhenitsyn also describes the finely graduated ranking among the prisoners. The criminal prisoners were often punished more leniently and treated better in the prison camp than their political opponents because they were not “elements of alien class”. The political opponents, on the other hand (or whoever was believed to be), were considered opponents of the working class and counter-revolutionaries ; they were harassed. Solzhenitsyn also writes about attempts to escape, which, however, were limited by the vastness and inhospitable nature of the country, the adverse weather conditions and the depressed prisoners.

In Part IV ( Soul and Barbed Wire ) Solzhenitsyn dares to look into the mental life and feelings of the prisoners. He writes about how fixed-term detention and uncertainly long-term camp detention change people. In his opinion, there were few opportunities in the prison camp to show consideration for one another, to help one another or to learn something positive. Because life in the penal camp was set up in such a way that “for every survivor there is one or two deaths.” The food rations were e.g. B. not distributed evenly to everyone, but in such a way that at least two prisoners had to fight for it. In the last chapter of Part IV, Solzhenitsyn writes about the impact of the prison system on the free population of the Soviet Union. He describes how many of Stalin's contemporaries lived in a climate of fear and mistrust and could only survive through cunning and cunning, and how some of them were even driven to the point of betrayal.

In Part V The Katorga Comes Again and Part VI In Exile Solzhenitsyn describes the psychology of the Gulag residents and compares their fate within the exile with that of imprisonment in the notorious prisons “at home”.

Part VII After Stalin gives a critical outlook on the post-Stalin 1960s.

reception

Shortly after the publication of the Gulag archipelago , Alexander Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Union on February 14, 1974 and lived in Zurich and later in the US state of Vermont for seventeen years . In 1994 he returned to Russia.

In the west, The Gulag Archipelago was regarded as an important political and literary testimony to the Cold War and the title gave it its name to the prison camp region of the Soviet Union. In the United States and England, this comprehensive report reinforced the rejection of the Soviet-style communist system and communism in general. In popular culture, the word “gulag” has become a synonym for banishment and extermination through segregation. In the Federal Republic of Germany, however, critical attitudes towards the Soviet Union were already so widespread that Solzhenitsyn was even taken under protection by representatives of the New Left. Nevertheless, there was a lively discussion about the content of the work. However, the portrayal of the Nazi collaborators and the Gestapo in the Gulag Archipelago was heavily criticized by left-wing intellectuals such as Friedrich Hitzer.

In the Romance countries, especially in France, where prominent scholars, intellectuals and artists had supported communist parties as members or sympathizers, they often turned away from these parties and in France sometimes from the ideas of socialism completely. Long before the end of the Soviet Union, this movement weakened and disillusioned the formerly strong communist parties in Italy, France and Spain. The remaining communists waged heavy ideological battles over whether the model of the Soviet Union, the dictatorship of the proletariat under the leadership of the Communist Party as the vanguard of the working class, which had hitherto been almost uncritically supported, should continue to be unconditionally supported or whether communism, in particular the socialization of the means of production, should be suppressed Preservation of human rights - and thus at a distance from the Soviet model - should be sought. This latter movement, known as " Eurocommunism ", prevailed in Italy under the party leader Enrico Berlinguer , the orthodox tendency was able to gain a foothold in France and Spain, where the mass of communist voters long before the unmistakable severe economic crises of the communist states of Eastern Europe to the socialist ones Parties migrated.

The book was also published by some of the conspiratorial opposition publishers of the Solidarność movement in Poland in the 1980s.

The income from The Gulag Archipelago went to an aid fund founded by Solzhenitsyn, which dissidents in the USSR used to support political prisoners and their families. This fund continued to help former Gulag prisoners after 1991.

The archive-based scientific research into Stalinism since the end of the 20th century supplements Solzhenitsyn's subjective source work with differentiating aspects such as the role of camps in the Soviet economy, for example through the implementation of large infrastructure projects such as the White Sea-Baltic Canal , the expansion of the Trans-Siberian Railway or the coal and oil production in the Vorkuta labor camp and the institutional disputes within the Soviet repressive apparatus.

Award

- The Gulag archipelago is one of the 100 books of the century by the French daily Le Monde .

Web links

- Archipelago Gulag (full text, Russian) Part 1 and 2 , Part 3 and 4 , and Part 5, 6, and 7

- The cold pole of cruelty Neue Zürcher Zeitung , March 16, 2002 (on the genre of Russian camp literature)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sonja Hauschild: Prophets or Troublemakers? Soviet dissidents in the Federal Republic of Germany and France and their reception among intellectuals (1974–1977). P. 30. (PDF file; 2.5 MB) Queryed on December 27, 2010.

- ↑ Solzhenitsyn: The GULAG Archipelago Der Spiegel , January 21, 1974

- ↑ Solzhenitsyn's "Archipel Gulag" is very topical Die Welt , December 27, 2013

- ↑ Elisa Kriza: Archipel Gulag dekoder.org , September 30, 2015

- ↑ In the film Mad Max - Beyond the Thunder Dome (1985), a person is sentenced to the "Gulag"; in this case she is abandoned in a helpless position in the desert and left to certain death.

- ↑ Rudi Dutschke (Ed.): Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn and the Western Left. Reinbek near Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1975.

- ↑ Elisa Kriza: Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Cold War Icon, Gulag Author, Russian Nationalist? A Study of His Western Reception . Ibidem, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-8382-0690-5 , pp. 113-131.

- ↑ Elisa Kriza: Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Cold War Icon, Gulag Author, Russian Nationalist? A Study of His Western Reception . Ibidem, Stuttgart 2014, pp. 194-199.

- ↑ Viktor Erofejew : "Archipel Gulag" destroyed the Soviet Union Die Welt , August 4, 2008

- ↑ Johannes Grützmacher: Milestone in literature and historiography. Solženicyns “Archipel Gulag” from today's perspective , in: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History 3 (2006), pp. 475–479

- ↑ Information about the Aid Fund for Political Prisoners ( accessed December 10, 2011)

- ↑ Johannes Grützmacher: Milestone in literature and historiography. Solženicyns “Archipel Gulag” from today's perspective , in: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History 3 (2006), pp. 475–479