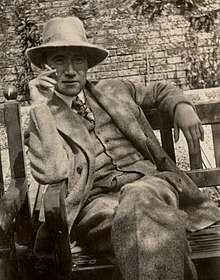

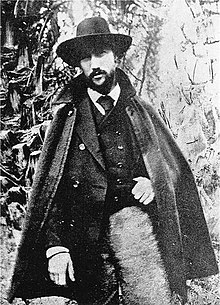

André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide [ ɑ̃dˈʁe pɔl ɡiˈjom ʒiːd ] (born November 22, 1869 in Paris , † February 19, 1951 ibid) was a French writer . In 1947 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature .

Life and work

Origin, youth and marriage

André Gide was the only child of a wealthy Calvinist family. The father, Paul Gide (1832–1880), was a professor of law and came from the middle bourgeoisie of the small town of Uzès in the south of France , the mother, Juliette Rondeaux (1835–1895), from the big bourgeoisie of Rouen . The family lived in Paris, regularly spent the New Year's in Rouen, Easter in Uzès and the summer months on the two country estates of the Rondeaux in Normandy , La Roque-Baignard in the Pays d'Auge and Cuverville in the Pays de Caux .

Gide lost his father when he was just under eleven. Although this did not result in any material emergency, he was now completely subject to the puritanical upbringing of his mother. In his autobiography, Gide will paint his own childhood and youth, especially the work of the strict, joyless and loveless mother, in dark colors and blame him for his problems as an adolescent: “In the innocent age when one likes nothing but in the soul Seeing purity, tenderness and purity, I only discover darkness, ugliness and insidiousness. ”Gide had been taking lessons from private teachers since 1874, and at times also attended regular schools, repeatedly interrupted by nervous disorders that required medical treatment and spa stays. In October 1887, the almost 18-year-old Gide entered the lower class of the educational reformist École Alsacienne , where he made friends with Pierre Louÿs . In the following year he attended the upper prima of the traditional high school Henri IV , where he passed the Baccalauréat in October 1889 . During this time his friendship with Léon Blum began .

During a visit to Rouen in December 1882, Gide fell in love with his cousin Madeleine Rondeaux (1867-1938), the daughter of Juliette Gide's brother Émile Rondeaux. At that time, 13-year-old André experienced how much his cousin suffered from her mother's marital infidelity and from then on saw in her the epitome of purity and virtue in contrast to his own perceived impurity. This childhood love lasted the following years and in 1891 Gide Madeleine proposed marriage for the first time, which she refused. It was only after Juliette Gide's death in May 1895 that the couple became engaged and married in October 1895, at a time when Gide had already become aware of his homosexuality . The tension that arose from this will shape Gide's literary work - at least until 1914 - and put a heavy strain on his marriage. The relationship he entered into with Marc Allégret from 1917 onwards , Madeleine could no longer forgive him, which is why in 1918 she burned all the letters he had ever written her. Although the couple stayed married, both now mostly lived separately. After Madeleine's death in 1938, Gide reflected on their relationship - "the hidden tragedy" of his life - in Et nunc manet in te . The writer friend Jean Schlumberger dedicated the book Madeleine and André Gide to this marriage , in which Madeleine finds a fairer representation than in Gide's autobiographical writings.

Literary beginnings

After completing his baccalaureate, Gide decided against studying and was not forced to pursue gainful employment. His goal was to become a writer. He had already made his first attempts during school when he founded the literary magazine Potache-Revue with friends, including Marcel Drouin and Pierre Louÿs, in January 1889 and published his first verses there. In the summer of 1890 he went alone to Menthon-Saint-Bernard on Lac d'Annecy to write his first book: Les Cahiers d'André Walter (“The Diaries of André Walter”), which he had printed at his own expense ( like all works up to 1909!) and which appeared in 1891. Gide's autobiographical first work is in the form of a posthumously found diary of the young André Walter, who, after having given up hope in his beloved Emmanuèle, withdrew into solitude to write the novel Allain ; the diary documents his path into madness. While the André Walter was being prepared for printing, Gide visited his uncle Charles Gide in Montpellier in December 1890 , where he - mediated by Pierre Louÿs - met Paul Valéry , whom he later (1894) facilitated his first steps in Paris and whom he up to whose death in 1945 was to remain on friendly terms.

Although the André Walter Gide did not bring commercial success (“Yes, the success was zero”), it did give him access to important circles of symbolists in Paris. Again mediated by Pierre Louÿs, he was accepted into the circles of José-Maria de Heredia and Stéphane Mallarmé in 1891 . There he associated with famous writers of his time, including Henri de Régnier , Maurice Barrès , Maurice Maeterlinck , Bernard Lazare and Oscar Wilde , with whom he was in regular contact in 1891/92. Gide himself delivered the small treatise Traité du Narcisse in 1891 . Théorie du symbole ("Treatise from Narcissus. Theory of Symbols") is a symbolist program script that is of fundamental importance for understanding his poetics - even beyond its symbolist beginnings. In the Narcissus myth , Gide creates his own image as a writer who mirrors himself, is in permanent dialogue with himself, writes for himself and thereby creates himself as a person. The genre appropriate to this attitude is the diary that Gide has consistently kept since 1889, supplemented by other autobiographical texts; but also in his narrative works the diary is omnipresent as a means of representation.

In 1892 Gide published the poetry book Poésies d'André Walter ("The Poems of André Walter"), in which a selection was offered from those verses that the student had already published in Potache-Revue . In February 1893 he met in the literary circles of Paris Eugène Rouart (1872-1936) know, who introduced him to Francis Jammes . The friendship with Rouart, which lasted until his death, was of great importance to Gide because he found a communication partner in the friend, who was also homosexual, who was driven by the same search for identity. The correspondence of both, especially in 1893 and 1895 shows the careful probing dialogue, for example through the 1893 published in French factory The contrary sexual instinct of Albert Moll was performed. In 1893, Gide published the short story La Tentative amoureuse (“The attempt at love”), the main plot of which consists of an unrestrained love story, the slightly ironic end credits, however, addressing a “Madame” who is visibly more difficult than the mistress of the main plot. In the same year he wrote the lyrical long story Le Voyage d'Urien ("The Journey of Urians"), where he once again addresses the difficult search of an idle, materially carefree young intellectual for "real life" in the form of a fantastic travel report.

Africa trips 1893/94 and 1895

In 1893 Gide had the opportunity to accompany his friend, the painter Paul-Albert Laurens (1870–1934), to North Africa. The friends crossed from Marseille to Tunis in October , traveled on to Sousse , spent the winter months in Biskra, Algeria, and returned via Italy. Gide had been exempted from military service in November 1892 because of mild tuberculosis ; the disease broke out during the trip to Sousse. The months in Biskra were used for regeneration and were connected with the first heterosexual contact with young prostitutes. Even more significant for Gide was the first homosexual experience with a young person, which had already happened in Sousse. Gide experienced the slow recovery and the awakened sensuality in the North African landscape as a turning point in his life: “It seemed to me as if I had never lived before, as if I were stepping out of the valley of shadows and death into the light of real life new existence in which everything would be expectation, everything would be surrender. "

Returning from the trip, Gide felt a "feeling of alienation" from his previous living conditions, which he processed in the work Paludes ("Swamps"), which was created during a stay in La Brévine in Switzerland (October to December 1894). In Palude he caricatures the idleness in the literary circles of the capital, not without melancholy, but also his own role in it. In January 1895 Gide traveled again to North Africa, this time alone. His whereabouts were Algiers , Blida and Biskra. In Blida he happened to meet Oscar Wilde and his lover Alfred Douglas . Wilde, who at this point was about to return to England, which was supposed to destroy him socially, organized a sexual encounter between Gide and a young person (Mohammed, around 14 years old), whom Gide was central to in his autobiography, during a joint stay in Algiers Importance is attached: "(...) only now did I finally find my own norm."

Gide has made numerous other trips to Africa in his life; his honeymoon already took him back to North Africa in 1896. Klaus Mann compared the historical significance of the first two trips to Africa for Gide, “the delight of a real new birth”, with Goethe's experience of Italy . Gide processed this experience in central texts of his literary work: in lyrical prose in Les Nourritures terrestres (“Uns nutrition die Erde”, 1897), as a problem-oriented story in L'Immoraliste (“The Immoralist”, 1902), and finally autobiographical in Si le grain ne meurt ("Die and become", 1926). The autobiography in particular caused controversial debates because of its open commitment to homosexuality; later it was considered a milestone in the development of gay self-confidence in western societies. Meanwhile, the perspective has changed: the questions raised by Gide in Die and am : “In the name of which God, which ideals do you forbid me to live according to my nature? And where would this nature lead me if I just followed it? ”Must be answered today with reference to abuse and sex tourism .

Establishment as an author

After returning from Africa, Gide spent two weeks in the company of his mother in Paris before she left for the La Roque estate, where she died on May 31, 1895. The tense relationship between mother and son had recently become more conciliatory and Juliette Gide had given up her opposition to Madeleine and André getting married. After her death, the couple became engaged on June 17 and married on October 7, 1895 in Cuverville. Gide later reported that even before the engagement he saw a doctor to discuss his homosexual tendencies. The doctor recommended marriage as a cure ("You seem like a starving man who has tried to feed on pickles to this day."). The marriage was probably never consummated, Gide made a radical distinction between love and sexual desire. The honeymoon went to Switzerland, Italy and North Africa (Tunis, Biskra). His travel notes Feuilles de route (“Leaves on the Go”) leave out the marital problems and concentrate entirely on the sensual presence of nature and culture. Upon her return, Gide learned in May 1896 that he had been elected mayor of the village of La Roque-Baignard. He held this office until the La Roque estate was sold in 1900. The Gides only retained Madeleine's Cuverville heritage.

Les Nourritures terrestres appeared in 1897 . Since the first translation into German by Hans Prinzhorn in 1930, this work was known under the title Uns nahrung die Erde , the more recent translation by Hans Hinterhäuser translated The Fruits of the Earth . Gide had worked on the text since the first trip to Africa, the first fragments of which were published in the magazine L'Ermitage in 1896 . Gide expresses his experience of liberation in a mixture of lyric poetry and hymn-like prose: in rejecting the opposition between good and bad, in advocating sensuality and sexuality in every form, in celebrating intoxicating enjoyment against reflection and rationality. With this work, Gide turned away from symbolism and the salon culture of the Parisian fin de siècle . It gained him admiration and following among younger writers, but was initially not a commercial success; until the First World War only a few hundred copies were sold. After 1918, however, Les Nourritures terrestres developed "into the Bible for several generations".

Gide barely emerged as a political writer in his early years. His anti-naturalism sought works of art "that stand outside time and all" contingencies "". In the Dreyfus affair, however, which divided the French public since 1897/98, he clearly positioned himself on the side of Emile Zola and in January 1898 signed the petition of the intellectuals in favor of a revision procedure for Alfred Dreyfus . In the same year he published the article A propos der "Déracinés" in the magazine L'Ermitage , in which he opposed Maurice Barrès' nationalist theory of uprooting on the occasion of the publication of the novel Les Déracinés ("The Uprooted"). The story Le Prométhée mal enchaîné (“The ill-fettered Prometheus”), published in 1899 and revolving around the motif of the acte gratuit , a completely free, arbitrary act , then completely corresponded to the absolute artistic ideal .

Gide showed an early interest in the German-speaking cultural area. Even as a schoolboy he was enthusiastic about Heinrich Heine , whose book of songs he read in the original. In 1892 his first trip to Germany took him to Munich . Soon personal contacts arose with German-speaking authors, such as the symbolist and poet Karl Gustav Vollmoeller , whom he met in 1898 and visited in his summer residence in Sorrento that same year . Gide came into contact with Felix Paul Greve through Vollmöller in 1904 . It was during this time that he became acquainted with Franz Blei . Greve and Blei emerged as early Gides translators into German. At the invitation of Harry Graf Kessler , Gide visited Weimar in 1903 and gave the lecture on the importance of the audience in front of Princess Amalie at the Weimar court . Gide was to campaign for Franco-German relations all his life, especially after 1918. Goethe and Nietzsche are to be emphasized in terms of spiritual influences ; Gide has dealt intensively with the latter since 1898.

At the turn of the century, Gide increasingly turned to dramatic works. His scenic works tie in with materials from ancient tradition or biblical stories. At the center of his idea dramas are characters on whom Gide projects his own experiences and ideas. In the lecture De l'évolution du théâtre (“On the Development of Theater”), which was important for his dramaturgical considerations , held in Brussels in 1904 , Gide quotes Goethe approvingly: “For the poet, no person is historical, he likes a moral world and for this purpose he does certain people from history the honor of lending their names to his creatures. "The text Philoctète ou Le Traité des trois morales (" Philoctete or the treatise of the three species . "published in the magazine La Revue blanche in 1898) of virtue ”) was based on Sophocles and had the character of a treatise in dramaturgical form; a performance was neither planned nor actually realized. The first Gides drama to hit the stage was Le roi Candaule ("King Kandaules ") in 1901 , from which Herodotus' Histories and Plato's Politeia were taken. The work was premiered on May 9, 1901 in the direction of Aurélien Lugné-Poes in Paris. The translation by Franz Bleis was performed in 1906 at the Deutsches Volkstheater in Vienna . In 1903 Gide published the drama Saül ("Saul"), which is based on the book Samuel . The piece was completed in 1898, but Gide only published it after all attempts to get it to perform had failed. In fact, Saul was not premiered until 1922 by Jacques Copeau at the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in Paris. Although Gide did not present a major drama again until 1930 after this intensive theatrical work around 1900 with Œdipe ("Oedipus"), he always remained connected to the theater. This is shown, for example, by his translations of William Shakespeare's Hamlet and Antonius and Cleopatra or of Rabindranath Tagore's Das Postamt ; Gide's opera libretto for Perséphone , which Igor Stravinsky set to music , also demonstrates his theatrical interest. In 1913, Gide himself was one of the founders of the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier .

Gide mostly worked on several works at the same time, which matured over years and were in a dialectical relationship to one another. This applies in particular to two of his most important stories before 1914: L'Immoraliste (“The Immoralist”, 1902) and La Porte étroite (“The narrow gate”, 1909), which Gide himself referred to as “twin (s)” who “ grew in my mind in competition with one another ”. The first reflections on both texts, which were intended to deal with the problem of virtue from different perspectives, go back to the time after returning from the first trip to Africa. Both narratives are strongly autobiographical in the locations and in the personal constellations, which is why it was obvious to recognize Madeleine and André Gide in Marceline and Michel (in the Immoralist ) and in Alissa and Jérôme (in The narrow gate ). Gide has always rejected this equation and used the image of various buds that he carried as traits: the figure of Michel could grow from one of these buds, who gave himself completely to absolute, self-centered vitality and sacrificed his wife for it; from another bud emerged the figure of Alissa, who sacrifices her love to the absolute and blind following of Christ . Both figures fail in their opposite radicalism, both embody Gide's tendencies and temptations, which he does not drive to extremes, but - here too, following the example of Goethe - tries to unite and balance them.

In 1906 Gide acquired the Villa Montmorency in Auteuil , where he lived until 1925, unless he was in Cuverville or traveling. During this time, Gide mainly worked on The Narrow Gate . He interrupted this work in February and March 1907 and completed the short story Le Retour de l'enfant prodigue ("The Return of the Prodigal Son"), which appeared in the spring of 1907. The story takes up the biblical motif of the homecoming of the prodigal son , who in Gide advises the younger brother, however, to leave the parental home as well and not to come back. H. to definitely emancipate yourself. The story appeared as early as 1914 in a German translation by Rainer Maria Rilke and developed - especially in Germany - "into a confessional book of the youth movement ". According to Raimund Theis, The Return of the Prodigal Son is “one of André Gide's most formally closed, most perfect poems”. Soon after completing the Prodigal Son , in July 1907, Gide visited his friend Eugène Rouart on his estate in southern France. There it came to a night of love between Gide and the 17-year-old farm laborer's son Ferdinand Pouzac (1890-1910), which Gide processed in the short story Le Ramier ("The Wood Pigeon"), which was only published in 2002 from his estate.

Since Les Nourritures terrestres, a group of younger writers has formed around Gide , consisting of Marcel Drouin, André Ruyters, Henri Ghéon , Jean Schlumberger and Jacques Copeau. The group planned to found a literary magazine according to their ideas after L'Ermitage , in which Gide had also published since 1896, had died in 1906. Together with Eugène Montfort, Gide's group prepared the first issue of the new periodical for November 1908, which was to be entitled La Nouvelle Revue française ( NRF ). After differences with Montfort, they separated and the six friends founded the magazine under the same name with a new first issue, which appeared in February 1909. The magazine quickly won over well-known authors of the time, including Charles-Louis Philippe , Jean Giraudoux , Paul Claudel , Francis Jammes, Paul Valéry and Jacques Rivière . The NRF was affiliated with its own publishing house in 1911 ( Éditions de la NRF ), which was managed by the soon-to-be influential publisher Gaston Gallimard . Gide's story Isabelle was published in 1911 as the third book by the new publisher. After 1918, through the magazine and the NRF publishing house, Gide became one of the leading French writers of his era, who maintained contacts with almost all contemporary European authors of high standing. The rejection of the first volume of Marcel Proust's novel In Search of Lost Time by the publisher in 1912 went down in literary history : Gide was the editor with the main responsibility and justified his vote with the fact that Proust was "a snob and literary amateur" be. Gide later admitted his mistake to Proust: "The rejection of the book will remain the greatest mistake of the NRF and (because I am ashamed to be largely responsible for it) one of the most stabbing pains and remorse of my life."

Gide divided his narrative works into two genres : the Soties and the Récits . Among the soties he counted Urian's Journey , Paludes and The Badly Fettered Prometheus , the Récits The Immoralist , The Narrow Gate , Isabelle and the 1919 Pastoral Symphony . While the Sotie works with satirical and parodistic stylistic devices, the Récit can be characterized as a narrative in which a figure is presented as an ideal type, removed from the fullness of life, as a case. Gide clearly separated both genres from the totality of the novel , which meant that he had not yet submitted a novel himself. Even the work Les Caves du Vatican (“The Dungeons of the Vatican”), published in 1914 , he did not count as a novel, despite the complex plot, but counted it among his soties . Against the background of real rumors in the 1890s that Freemasons had Leo XIII. Imprisoned and replaced by a false pope, Gide creates an image of society full of falsehood and hypocrisy, in which religion, belief in science and civic values are reduced to absurdity by his figures, all of them fools. Only the dazzling figure of the beautiful young cosmopolitan Lafcadio Wluiki, completely free and without ties, seems to have a positive connotation: - and he commits a murder as “acte gratuit”. When they appeared, the Vatican dungeons met with some positive feedback, which Proust's enthusiasm may represent, and some with severe criticism, which is characteristic of Paul Claudel's rejection. Claudel, who was friends with Gide, wanted to convert him to Catholicism in the years before 1914 and Gide seemed close to conversion in phases. Claudel could only understand the new work as a rejection, especially since the book also contains a satirical conversion. Claudel's criticism, expressed in a letter to Gide in 1914, began with a homoerotic passage: “For God's sake, Gide, how could you write the paragraph (...). So is it really to be assumed - I have always refused to do so - that you yourself practice these appalling customs? Answer me. You have to answer. "And Gide replied in a way that shows that he was tired of the double life he led (even if the public confession did not follow until after 1918):" I have never felt any desire in a woman; and the saddest experience I have had in my life is that the most enduring, longest, most vivid love was not accompanied by what generally precedes it. On the contrary: love seemed to me to prevent desire. (...) I didn't choose to be like that. "

First World War and breakthrough in the interwar period

After the outbreak of World War I , Gide, who was not called up for military service, was involved in the private aid organization Foyer Franco-Belge until spring 1916 , which looked after refugees from areas occupied by German troops. There he worked with Charles Du Bos and Maria van Rysselberghe, the wife of the Belgian painter Théo van Rysselberghe . Maria (called La Petite Dame ) became a close confidante of Gides. Since 1918, without his knowledge, she made notes of encounters and conversations with him, which were published between 1973 and 1977 under the title Les Cahiers de la Petite Dame . With the daughter of the Rysselberghes, Elisabeth, Gide fathered a daughter in 1922: Catherine Gide (1923–2013), whom he kept from Madeleine and only officially recognized as a daughter after her death in 1938. After the sale of the villa in Auteuil, Gide lived mostly in Paris from 1926 in a house on rue Vaneau with Maria, Elisabeth and Catherine, while Madeleine retired entirely to Cuverville.

The years 1915-16 were overshadowed by Gide's deep moral and religious crisis. He was unable to reconcile his way of life with the religious imprints deeply rooted in him. In addition, for years he experienced the attraction that Catholicism exerted on people close to him. This was not only true for Claudel, but also for Francis Jammes, who had converted in 1905. Henri Gheon followed in 1915, then Jacques Copeau, Charles Du Bos and Paul-Albert Laurens. In a diary entry from 1929 Gide admitted: "I do not want to say that at a certain point in my life I was not quite close to converting." As a testimony to his religious struggles, Gide published a small edition in 1922 (70 copies ) Anonymous the font Numquid et tu ...? ; In 1926 he had a larger edition (2,650 copies) followed under his own name.

Gide overcame the crisis through love for Marc Allégret . He had known Marc, born in 1900, since he was a family friend. Marc's father, the pastor Élie Allégret (1865–1940), had taught Gide as a child and had considered him like a younger brother ever since. When he was sent to the Cameroon Mission in 1916 , he entrusted Gide with the care of his six children. This fell in love with the fourth oldest son Marc and had an intimate relationship with him since 1917; for the first time he experienced the match between love and sexual desire. Gide and Allégret went on trips, to Switzerland in 1917 and to England in 1918. The downside of this happiness was the serious crisis in the relationship with Madeleine. In 1916 she found out about her husband's double life by chance and was so deeply injured by his month-long stay in England with Marc that she reread all the letters Gide had written to her over 30 years and then burned them. When Gide found out about it in November 1918, he was deeply desperate: "This will make my best disappear (...)." Against the background of these emotional vicissitudes, the story La Symphonie pastorale ("The Pastoral Symphony") was written in 1918 and published in 1919 has been. It was the story of a pastor who takes a blind orphan girl into his family, raises her, falls in love with her, but loses her to his son. The symphony was Gide's greatest book success in his lifetime, with more than a million copies and around 50 translations. In the same year, the Nouvelle Revue française , which had been discontinued since 1914, was published for the first time after the war. During this time Gide's rise to the central figure in literary life in France took place: le contemporain capital , the most important contemporary , as the critic André Rouveyre wrote.

In the years after the First World War, Gide's increasing reception in Germany fell, for which the Romanist Ernst Robert Curtius was of great importance. In his work The literary trailblazers of the new France , published in 1919 , he paid tribute to Gide as one of the most important contemporary French authors. An exchange of letters had developed between Curtius and Gide since 1920 that lasted until Gide's death. As early as 1921, the two of them met in person for the first time in Colpach, Luxembourg . The industrial couple Aline and Emil Mayrisch organized meetings of French and German intellectuals in the local castle . Gide had known Aline Mayrisch, who wrote about German literature for the NRF , since the beginning of the century. She and Gide also arranged for Curtius to be invited to the second, regular meeting of intellectuals committed to European understanding: the Decades of Pontigny , which Paul Desjardins had organized since 1910. The decades interrupted during the war took place again for the first time in 1922 and Gide, who had been there before 1914, was one of the regular participants. The friendship between Gide and Curtius, based on mutual respect, was also based on the mutual rejection of nationalism and internationalism ; both advocated a Europe of cultures . Ernst Robert Curtius has also translated Gide's works into German.

In 1923, Gide published a book on Dostoyevsky : Dostoïevsky. Articles et causeries ("Dostojewski. Essays and Lectures"). He had dealt with the Russian novelist since 1890, when he first read the book Le Roman russe by Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé . Vogüé's work, published in 1886, popularized Russian literature in France and introduced Dostoyevsky in particular as a representative of a “religion of suffering”. Gide turned against this interpretation from the first reading and emphasized the psychological qualities of the Russian narrator, who in his characters illuminates the most extreme possibilities of human existence. He published several articles about Dostoevsky and planned a biography before 1914, which he never presented. On the occasion of his 100th birthday in 1921 he gave a lecture at the Vieux-Colombier Theater , from which a series of lectures developed in 1921/22. The work, published in 1923, collected older essays and the lectures in the Vieux-Colombier that had not been further edited. Gide made it clear that his view of Dostoevsky had not changed with Nietzsche's remark that Dostoevsky was “the only psychologist from whom I had to learn something”, which he put in front of the book as the motto. The publication on Dostoyevsky is Gide's most comprehensive discussion with another writer, which fell precisely in the years in which he himself was working on a theory of the novel. Gide's interest in Russian literature is also shown by his translation of Pushkin's novellas, submitted in 1928 .

In the mid-1920s, Gide's work culminated in the publication of three books that he had worked on for years and that finally defined him as a public figure as well as an artist: Corydon was published in 1924 . Quatre dialogues socratiques ("Corydon. Four Socratic Dialogues"), 1926 Si le grain ne meurt ("Die and become") and in the same year Les Faux-Monnayeurs ("The counterfeiters"). With Corydon and Die and Go, Gide came out as a homosexual in public. For him, this was a stroke of liberation as he increasingly felt his private life and public image to be false and hypocritical. In a draft foreword to Die and Will , he named his motivation: “I mean, it is better to be hated for what you are than to be loved for what you are not. I believe I suffered the most in my life from lies. "

Corydon had a long history of origins. Since 1908, Gide worked on Socratic dialogues on the subject of homosexuality. In 1911 he published an anonymous edition of 22 copies under the title CRDN . At this point the first two and part of the third dialog had been completed. Before the war, Gide continued to work, interrupted it in the first years of the war and resumed it from 1917. He had the resulting text, again anonymously, printed in an edition of only 21 copies, which already had the title Corydon. Four Socratic dialogues contributed. After further editing since 1922, the book was published in May 1924 under Gide's name, and in 1932 for the first time in German in a translation by Joachim Moras . Corydon combines the fictional literary form of dialogue with non-fictional content, which the two interlocutors share (history, medicine, literature, etc.). Gide's concern was to defend homosexuality as given by nature, preferring the variety of pederasty .

The origin of the autobiography Die and Will , which depicts Gide's life up to his marriage in 1895, goes back to the years before the First World War. In 1920 Gide had a private print (12 copies) of the first part of the memoir made, which was only intended for his friends; In 1921, 13 copies of the second part followed for the same purpose. The edition intended for the book trade was available in print in 1925, but was not delivered until October 1926 at Gide's request. Die and become is a description of life that does not follow the pattern of organic growth or the gradual development of personality, but rather represents a radical change: the time before the Africa trip (part I) appears as a dark epoch of self-alienation, the experiences in Africa (part II) as liberation and redemption of one's self. Gide was aware that such a stylized meaning in his own life description simplified reality and harmonized the contradictions in his being. In a self-reflection included in the autobiography, he remarked: “As much as one strives for truth, the description of one's own life is always only half-honest: in reality everything is much more complicated than it is presented. Perhaps one even comes closer to the truth in the novel. ”With the counterfeiters , he redeemed this claim.

In the dedication of the work to Roger Martin du Gard, Gide described The Counterfeiters as his “first novel” - and according to his own definition of the novel, it remained his only one. He had started work on the book in 1919 and completed it in June 1925. It was published in early 1926 with the copyright dated 1925 . Parallel to the creation of the novel, Gide kept a diary in which he recorded his reflections on the developing work. This text appeared in October 1926 under the title Journal des Faux-Monnayeurs ("Diary of the counterfeiters"). The Counterfeiters is a very artistically designed novel about the creation of a novel. The plot, which begins with one of the protagonists discovering that he was procreated out of wedlock, seems a bit confusing, but is on par with the contemporary theoretical and narrative achievements of the novel genre, which in the meantime had become a problem in itself. The Faux-Monnayeurs are now regarded as a trend-setting work of modern European literature.

Turn to the social and political

In 1925 Gide sold his villa in Auteuil and went with Allégret on an almost one-year trip through the French colonies of Congo ( Brazzaville ) and Chad . He then described what he considered to be untenable exploitative conditions there in lectures and articles as well as in the books Voyage au Congo (“Congo Travel”) (1927) and Retour du Tchad (“Return from Chad”) (1928), which sparked heated discussions and attracted many attacks by nationalist French. In 1929 L'École des femmes (“The School of Women”) appeared, the diary-like story of a woman who unmasked her husband as a rigid and soulless representative of bourgeois norms and left him to care for the wounded in the war.

In 1931 Gide took part in the wave of antiquated dramas triggered by Jean Cocteau with the play: Œdipe (" Oedipus ").

From 1932, in the context of the growing political polarization between left and right in France and all of Europe, Gide became increasingly involved on the side of the French Communist Party (PCF) and anti-fascist organizations. So he traveled z. B. 1934 to Berlin to demand the release of Communist opponents of the regime. In 1935 he was a member of the leadership of a congress of anti-fascist writers in Paris, which was financed partially covertly with money from Moscow. He defended the Soviet regime against attacks by Trotskyist delegates who demanded the immediate release of the writer Victor Serge interned in the Soviet Union . He also moderated - at least theoretically - the uncompromising individualism he had previously represented in favor of a position that puts the rights of the whole and of others before those of the individual.

In June 1936 he traveled for several weeks through the USSR at the invitation of the Soviet Writers' Union . He was looked after by the chairman of the association's foreign commission, the journalist Mikhail Kolzov . The day after Gide's arrival, the chairman of the Writers' Union, Maxim Gorky, died . Gide delivered one of the funeral speeches at the Lenin mausoleum , where the Politburo, headed by Stalin , had also taken up positions. But the audience he had hoped for with Stalin in the Kremlin did not materialize. According to research by literary historians, Stalin was well informed of Gide's intentions. Before he left, he had confided to the writer Ilya Ehrenburg, who worked in Paris as a correspondent for Soviet newspapers : "I have decided to raise the question of his attitude towards my like-minded people." Ehrenburg said he wanted to ask Stalin about the "legal situation of the pederasts " firmly.

However, Gide's disappointment when looking behind the scenes of the communist dictatorship was great. He described his impressions of this trip, which also took him to Georgia , in the critical report Retour de l'URSS (“Back from the Soviet Union”), in which he tried to avoid emotions and polemics. He described the Soviet regime as the “dictatorship of one man”, which had perverted the original ideas of the “liberation of the proletariat”. The Soviet press reacted with violent attacks on him, his books were removed from all libraries in the country, and a multi-volume edition that had already begun was not continued. When many Western Communists attacked him and accused him of indirectly supporting Hitler with his criticism , Gide completely distanced himself from the party.

World War II and the post-war period

After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, he retired to friends in the south of France and went to North Africa in 1942, after he had developed from a passive sympathizer of the head of government of the collaboration regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain to an active helper of the London government in exile under Charles de Gaulle . This he tried z. B. to support 1944 with a propaganda tour through the West African colonies, whose governors long wavered between Pétain and de Gaulle.

In 1946 Gide published his last major work, Thésée ("Theseus"), a fictional autobiography of the ancient legendary hero Theseus , into which he projects himself.

In his last years he was able to enjoy his fame with invitations to lectures, honorary doctorates, the award of the Nobel Prize in 1947, interviews, films about himself and the like. Ä. m. The reason for the Nobel Prize is: "for its extensive and artistically meaningful authorship, in which questions and relationships of humanity are presented with an fearless love of truth and psychological acumen".

In 1939, 1946 and 1950 his diaries appeared under the title Journal .

Gide described the extent of his disappointment and disenchantment with communism in a contribution to the book The God that failed published in 1949 , edited by Richard Crossman , Arthur Koestler et al. a.

In 1949 Gide received the Goethe plaque from the city of Frankfurt am Main . In 1950 he was elected as an honorary foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

An indirect recognition of its importance was that in 1952 all of his works were placed on the Roman Index of the Catholic Church.

Discovered and edited by his daughter in the estate , the homoerotic novella Le Ramier (English: The Wood Pigeon ) , composed in 1907 , was published posthumously in 2002 .

Works

Work chronology

- 1890: Les Cahiers d'André Walter (' The Notebooks of André Walter ')

- 1891: Le Traité du Narcisse ( ' Treatise on Narcissus ')

- 1892: Les Poésies d'André Walter ('The poems of André Walter')

- 1893: Le Voyage d'Urien (' The Journey of Urian ')

- 1893: La Tentative amoureuse ou Le Traité du vain désir (' The attempt at love or a treatise on the futility of desire')

- 1895: Paludes ('Paludes')

- 1897: Les Nourritures terrestres ('The fruits of the earth')

- 1899: Le Prométhée mal enchaîné (' The Badly Shackled Prometheus ')

- 1901: Le Roi Candaule ('King Kandaules'), play

- 1902: L'Immoraliste (' The Immoralist ')

- 1903: Saül ('Saul'), play

- 1907: Le Ramier (' Die Ringeltaube ') (first published in 2002, German 2006)

- 1907: Le Retour de l'enfant prodigue (' The Return of the Prodigal Son ')

- 1909: La Porte étroite (' The narrow gate ')

- 1911: Corydon. Quatre dialogues socratiques ('Corydon. Four Socratic Dialogues')

- 1911: Isabelle

- 1914: Les Caves du Vatican (' The dungeons of the Vatican ')

- 1914: Souvenirs de la Cour d'Assises ('Memories from the jury')

- 1919: La Symphonie pastorale (' The Pastoralsymphonie ')

- 1925: Les Faux-Monnayeurs (' The Counterfeiters ')

- 1926: Si le grain ne meurt (' Die and become ')

- 1927: Voyage au Congo ('Congo Journey')

- 1928: Le Retour du Tchad ('Return from Chad')

- 1929: L'École des femmes (' The School of Women ')

- 1930: Robert

- 1930: L'Affaire Redureau ('The Redureau Affair')

- 1930: La Séquestrée de Poitiers ('The Trapped in Poitiers')

- 1931: Œdipe ('Oedipus'), play

- 1934: Perséphone . Melodrama (oratorio). Music (1933/34): ' Igor Stravinsky '. Premiere 1934

- 1936: Geneviève (' Genoveva or An Unfinished Confession ')

- 1936: Retour de l'URSS ('Back from Soviet Russia')

- 1937: Retouches à mon Retour de l'URSS ('Retouching to my Russia Book')

- 1939: Et nunc manet in te (published 1947)

- 1946: Thésée (' Theseus ')

- 1949: Feuillets d'automne ('Autumn Leaves')

- 1939, 1946, 1950: Journal (diaries)

- 1993: Le Grincheux (posthumously, probably created 1925/26); ('The curmudgeon')

German editions

-

Hans Hinterhäuser / Peter Schnyder / Raimund Theis (eds.): André Gide: Collected works in twelve volumes. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1989–2000:

- Volume I (Autobiographical 1): Die and Become ; Diary 1889–1902

- Volume II (Autobiographical 2): Diary 1903–1922

- Volume III (Autobiographical 3): Diary 1923–1939

- Volume IV (Autobiographical 4): Diary 1939–1949 ; Et nunc manet in te ; Short autobiographical texts

- Volume V (Travel and Politics 1): Congo Travel ; Return from Chad

- Volume VI (Travel and Politics 2): Back from Soviet Russia ; Retouching to my Russia book ; Social pleadings

- Volume VII (Narrative Works 1): The notebooks of André Walter ; Treatise from Narcissus ; Urian's Journey ; The attempt at love ; Paludes ; The poorly bound Prometheus ; The immoralist ; The return of the prodigal son

- Volume VIII (Narrative Works 2): The narrow gate ; Isabelle ; The dungeons of the Vatican

- Volume IX (Narrative Works 3): The Counterfeiters ; Diary of the counterfeiters

- Volume X (Narrative Works 4): Pastoral Symphony ; The women's school ; Robert ; Genevieve ; Theseus

- Volume XI (Lyric and Scenic Poems): The poems of André Walter ; The fruits of the earth ; New fruits of the earth ; Philoctetes ; Saul ; King Kandaules ; Oedipus

- Volume XII (essays and notes): Dostojewski ; Corydon ; Notes on Chopin ; Records of literature and politics

- The narrow gate. Manesse-Verlag, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7175-1868-2

- Jury court. Three books on crime. Eichborn-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1997, series Die Other Bibliothek , ISBN 3-8218-4150-8

- The counterfeiters. Diary of the counterfeiters. Manesse-Verlag, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-7175-8265-8

- The wood pigeon. Narrative. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-421-05896-2

- The curmudgeon . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-95757-002-4

See also

literature

- Ernst Robert Curtius : André Gide . In: French Spirit in the Twentieth Century . Francke-Verlag, Bern 1952, pages 40-72. (First published in: The literary trailblazers of the new France . Kiepenheuer, Potsdam 1919.)

- Justin O'Brien: Portrait of André Gide. A critical biography . Octagon, New York 1977 ISBN 0-374-96139-5

- Ilja Ehrenburg : People - Years - Life (Memoirs), Munich 1962/1965, Volume 2: 1923–1941 ISBN 3-463-00512-3 pp. 363–368 Portrait Gides

- Jutta Ernst, Klaus Martens (Eds.): André Gide and Felix Paul Greve . Correspondence and Documentation . Ernst Röhrig University Press, St. Ingbert 1999

- Ruth Landshoff-Yorck: Gossip, Fame and Small Fires. Biographical impressions . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1963

- Frank Lestringant: André Gide l'inquiéteur. Flammarion, Paris 2011 ISBN 978-2-08-068735-7

- Klaus Mann : André Gide and the crisis of modern thinking . Steinberg, Zurich 1948

- Claude Martin: André Gide. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1963

- Peter Schnyder: André and Madeleine Gide in Lostdorf Bad . In: Oltner Neujahrsblätter , Vol. 43, 1985, pp. 46-50.

- Jean-Pierre Prevost: André Gide. Un album de famille. Gallimard, Paris 2010 ISBN 978-2-07-013065-8

- Maria van Rysselberghe: The little lady's diary. In the footsteps of André Gide. 2 volumes. Nymphenburger Verlag, Munich 1984

- Alan Sheridan: André Gide, a life in the present . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1999 ISBN 0-674-03527-5

- Raimund Theis: André Gide . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1974 ISBN 3-534-06178-0

Web links

- Literature by and about André Gide in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about André Gide in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about André Gide in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by André Gide in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Works by André Gide in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the awarding of the award to André Gide in 1947

- André Gide in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Roger Francillon: Gide, André. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Hans Christoph Buch : Whoever cheats, cheats on himself - About André Gide and his trip to the Soviet Union (1936) and his related book "Back from Soviet Russia" in the magazine Die Zeit 12/1995 [1]

- Biography and quotes from André Gide (French)

- Amis d'André Gide (French)

- Britta L. Hofmann Experimental Poetics. Poetics as an experiment Diss. Phil. Univ. Frankfurt, 2003, especially on the acte gratuit at AG (see chapter: L'Acte gratuit. The search for freedom, authenticity and availability, p. 266ff; at Gide above all in the dungeons )

Individual evidence

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: p. 74.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: pp. 170–174.

- ^ André Gide: Et nunc manet in te . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume IV. Stuttgart 1990, pp. 431–477, here: pp. 458 ff.

- ↑ So Raimund Theis: Foreword to this volume. In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 35–69, here: p. 46.

- ^ Jean Schlumberger: Madeleine and Andre Gide. Hamburg 1957.

- ↑ Timeline . In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 19–33, here: p. 21.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Kesting: To the booklets of André Walter. In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume VII. Stuttgart 1991, pp. 509-520, here in particular: p. 513.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: p. 280.

- ^ André Gide: Oscar Wilde in memoriam . In: Collected Works , Volume XII. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 351-371, here: pp. 352-359.

- ↑ Raimund Theis: Foreword to this volume. In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 35–69, here: p. 37 f.

- ^ Raimund Theis: Foreword. In: André Gide: Collected Works , Volume XI. Stuttgart 1999, pp. 9–21, here: p. 9

- ↑ Analyzed by David H. Walker: Afterword. In: André Gide: The wood pigeon. Munich 2006, pp. 31–67, here: 47–67.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: pp. 309–340 (first trip to Africa), p. 333 f. (Quote).

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Collected Works , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: p. 340.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: pp. 344–378 (second trip to Africa), p. 361 (quotation).

- ↑ Klaus Mann: André Gide and the crisis of modern thought. Hamburg 1984, p. 80.

- ↑ Tilman Krause: The long way to gay self-confession

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: p. 310.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: pp. 378–384.

- ^ André Gide: Et nunc manet in te . In: Collected Works , Volume IV. Stuttgart 1990, pp. 431–477, here: p. 441.

- ^ André Gide: Leaves on the way . In: Collected Works , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 443–477.

- ↑ Memories of the time as mayor: André Gide: Jugend . In: Collected Works , Volume IV. Stuttgart 1990, pp. 585-599.

- ↑ Edward Reichel: Nationalism - Hedonism - Fascism. The myth of youth in French politics and literature from 1890 to 1945. In: Thomas Koebner et al. (Ed.): “The new time moves with us”. The myth of youth. Frankfurt am Main 1985, pp. 150-173, here: p. 156.

- ↑ So Michel Winock: The Century of the Intellectuals. Konstanz 2007, p. 141.

- ^ So Gide in a self-characterization in a letter to Jean Schlumberger of March 1, 1935, printed in: Michel Winock: Das Jahrhundert der Intellektuellen. Konstanz 2007, pp. 805-807, quotation p. 805.

- ↑ Michel Winock: The Century of the Intellectuals. Konstanz 2007, p. 62 with note 71.

- ^ André Gide: Speaking of the «Déracinés» . In: Collected Works , Volume XII. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 388-392.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71–386, here: p. 253.

- ^ André Gide: Diary 1889-1902 . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 387–532, here: p. 492 with note 110 on p. 567.

- ^ André Gide: Diary 1903-1922 . In: Gesammelte Werke , Volume II. Stuttgart 1990, p. 746, note 53.

- ^ Raimund Theis: Foreword . In: Collected Works , Volume XI. Stuttgart 1999, pp. 9-21, here: 17 ff.

- ^ André Gide: Diary 1903-1922 . In: Collected Works , Volume II. Stuttgart 1990, p. 29 f. with note 4 on p. 741.

- ↑ Henry van de Velde. André Gide in Weimar: PDF pp. 229–230. Retrieved April 26, 2020 .

- ^ André Gide: About the development of the theater . In: Collected Works , Volume XI. Stuttgart 1999, pp. 262-274, quote from Goethe, p. 266.

- ^ [OV]: André Gide. (A conversation with the poet of “King Kandaules”.) Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 40 (1906) # 25, 6. (January 26, 1906) and Hermann Bahr : Der König Candaules. (Drama in three acts by André Gide. German rewrite by Franz Blei. First performed in the German People's Theater on January 27, 1906). Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 40 (1906) # 27, 12. (January 28, 1906) Book edition: Hermann Bahr: Glossen, 228-235.

- ↑ Jean Claude: To the scenic poems . In: Collected Works , Volume XI. Stuttgart 1999, pp. 469-491.

- ^ André Gide: Diary 1903-1922 . In: Collected Works , Volume II. Stuttgart 1990, p. 292.

- ↑ Raimund Theis: On The Immoralist. In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume VII. Stuttgart 1991, pp. 561–574, here: pp. 565 f.

- ↑ Raimund Theis: To The Return of the Prodigal Son. In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume VII. Stuttgart 1991, pp. 575-580, quotations: pp. 579 and 580.

- ^ André Gide: The wood pigeon. Munich 2006 (information based on the afterword by David H. Walker).

- ↑ Michel Winock: The Century of the Intellectuals. Konstanz 2007, pp. 143-146, 151.

- ↑ Marcel Proust - A writer's life . Documentary by Sarah Mondale, 1992, 60 min. - Produced by William C. Carter, George Wolfe and Stone Lantern Films.

- ↑ Quoted from Michel Winock: The Century of the Intellectuals. Konstanz 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Raimund Theis: Foreword . In: Collected Works , Volume IX. Stuttgart 1993, pp. 9-22, here: 10 f.

- ↑ Both letters quoted from Michel Winock: The Century of the Intellectuals. Konstanz 2007, p. 202.

- ^ Maria van Rysselberghe: Les Cahiers de la Petite Dame. Notes pour l'histoire authentique d'André Gide. 4 volumes. Gallimard, Paris 1973–1977.

- ↑ Pirmin Meier: Catherine Gide .

- ↑ Claude Martin: Gide. Reinbek bei Hamburg 2001, pp. 89–96, quoted on p. 90.

- ↑ Michel Winock: The Century of the Intellectuals. Constance 2007, p. 203 f.

- ^ André Gide: Et nunc manet in te . In: Collected Works , Volume IV. Stuttgart 1990, pp. 431–477, here: p. 458.

- ↑ Quoted from: Peter Schnyder: Foreword. In: André Gide: Gesammelte Werke , Volume X. Stuttgart 1997, pp. 9–23, here: pp. 10 f.

- ↑ Ernst-Peter Wieckenberg: Afterword. In: Ernst Robert Curtius: Elements of education. Munich 2017, pp. 219–450, here: pp. 267–274.

- ^ Brigitte Sendet: To Dostoevsky. In: André Gide: Collected works. Volume XII. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 441-449.

- ↑ Quoted from Claude Martin: Gide. Reinbek near Hamburg 2001, p. 108.

- ↑ Patrick Pollard: To Corydon. In: André Gide: Collected works. Volume XII. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 450-470, here: 451 ff. And 455 f.

- ↑ Raimund Theis: Foreword to this volume. In: André Gide: Collected works. Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 35-69, here: p. 54.

- ↑ Raimund Theis: Foreword to this volume. In: André Gide: Collected works. Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 35-69, here: p. 46.

- ^ André Gide: Die and become. In: Collected Works. Volume I. Stuttgart 1989, pp. 71-386, here: p. 308.

- ^ Raimund Theis: Foreword. In: André Gide: Collected works. Volume IX. Stuttgart 1993, pp. 9-22, here: p. 11 and p. 22.

- ↑ Boris Frezinskij: Pisateli i sovetskie voždi. Moscow 2008, p. 358

- ↑ cf. Fresinskij 2008, p. 424.

- ↑ cf. Fresinskij 2008, p. 423.

- ↑ cf. Fresinskij 2008, p. 421.

- ↑ cf. Fresinskij 2008, p. 429 f.

- ^ The God that failed, 1949, Harper & Brothers, New York. German version 1950: A God who wasn't, Europa Verlag

- ^ Honorary Members: André Gide. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 11, 2019 .

- ^ André Gide "The Wood Pigeon". Publishing site of the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt with a foreword by Catherine Gide ( Memento from September 12, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ).

- ↑ Critical Review Curtius essays: from Jürgen von Stackelberg, 2008, p 175ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gide, André |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gide, André Paul Guillaume (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 22, 1869 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | 19th February 1951 |

| Place of death | Paris |