diary

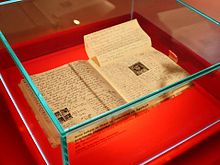

A diary , also diarium (Latin diarium ) or memoire ( French mémoire "written presentation", "memorandum") is an autobiographical record, i.e. a self-testimony in chronological form. It is often not written with the aim of publication. Published diaries, often written for this purpose, as well as literary or fictional works in this form make up the genre of diary literature .

features

The content of diaries is usually private; the diary follows the “line of one's own life” ( Max Dessoir ). It gives a fresh impression of what has been experienced. Experiences, own activities, but also moods and feelings are recorded in a diary. It is a medium of self-assurance and is characterized by a high degree of subjectivity. The evaluation of events and thoughts is often uncertain; often it only clears up in the long term. In many cases, private diaries are more direct and immediate than writings used for publication. Because: Anyone who "writes down a personal record with the awareness of a publication is self-censoring."

The style of a diary can be very different; Everything is possible “from the most unpretentious everyday prose to the level of the linguistic work of art” ( Peter Boerner ). The unsystematic and fragmentary aspect is typical of diaristics. Later entries need not be based on earlier ones. A characteristic of all diaries is the regularity of reporting; occasionally, however, the diary is interrupted in order to be resumed at a later point in time. People bear testimony about themselves and their environment in diaries, which can make private diaries from bequests an important source for historians .

history

Precursors of the diary in today's sense can be found in antiquity . An example of this are the Assyrian clay tablet calendars from the sixth century with notes on market prices, water levels, weather conditions and the like. The reports of acts of Babylonian rulers or Roman emperors, as well as records of dreams and their interpretation, are also the first attempts to record events. In the Middle Ages, chronicles , logbooks and records of mystics were the forerunners of the diary. However, all of these text forms are not yet records by individuals of personal experiences and thoughts or even banalities .

Diary writing in today's sense began in Europe with the Renaissance . Through the growing self- awareness of people and their self-confident stepping out of anonymity, opinions and representations of experiences gain in importance. Man becomes witness to many new experiences and developments that occur in this threshold period between the Middle Ages and modern times . A favorable technical development is the increasing spread of paper , which is an affordable writing material compared to parchment .

Simply registering everyday events, such as in logbooks or reports, is no longer sufficient. People want to process the new impressions and do so in observation and travel journals or memorial books. An example of this change is the anonymously written Journal d'un bourgeois de Paris . Here observations on current events from 1405 to 1449 are described and accompanied by comments. This text also makes subjective reactions to the social change of this time visible. Most of the diaries of this time are still chronicle diaries in which observation has priority over reflection. In Germany this was true until the 17th century.

The diary of the Englishman Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), one of the most cited works in English literature , looks completely modern. The State Secretary in the Naval Office regularly gave an account in the ten-volume, shorthand diary from January 1, 1660 to May 31, 1669. Rooted in the strict, lust-hostile Puritanism of Cromwell's time, Pepys wages a daily battle with his actual or supposed weaknesses, such as vanity, indulgence or sexual desire. On an equal footing with the events of the restoration era , he describes the sensitivities of one's own self with a previously unknown openness. In this way his joys and enjoyments are expressed as well as his fears of punishment, illness or death . In his diary, Pepys subjects his own behavior as well as those of others to a critical examination and thus bridges the gap between the objective-private diary of the Renaissance and the subjective-private diary of the present.

From the 18th century on, diaries became increasingly subjective. The citizen withdraws into the private sphere through the political system of absolutism . Religion, too, is increasingly subjectified, especially in Pietism, which is why many religious diaries were created that served as a means of soul research or as confession .

In the Enlightenment , the tendency to see the diary as a personal accountability report increases, while the sensitive diaries primarily describe their own feelings and perceptions psychologically. In the 19th century, the French journal intime takes up the first-person analysis of the sensitive diary and reinforces this tendency.

In 19th century Germany, authors like ETA Hoffmann or Friedrich Hebbel were influenced by French intimists . In the second half of the 19th century the diary becomes a little more objective again and serves as a literary workshop or memory aid.

Diary writing is becoming increasingly popular, especially in the 20th century. Exceptional situations , such as the two world wars and the political and social isolation during the National Socialist dictatorship , increasingly prompt people to write down their experiences in diaries. It produced diaries of victims of war and violence . The most famous work of this time is the diary of Anne Frank . The everyday historical value of diaries has been emphasized by Walter Kempowski since the 1980s , who set up an extensive archive at his place of residence in Nartum ( Kreienhoop house ). In 1998 the German Diary Archive followed in Emmendingen , which is organized as an association.

As forms of the 21st century, weblogs have established themselves as publicly accessible diaries and diary communities that link autobiographical events with time and place information, maps, photos and sounds. In a diary slam , people read their teenage diaries to an audience. Diary software that manages diary entries chronologically and enables search options also plays a role.

Special diaries are used for nautical ( logbook ) and military ( war diary ) purposes. The sleep diary , dream diary and reading diary have medical, psychological and educational uses .

Pain, therapy, healing

In important modern diaries, the reflection of emotional pain appears as a leitmotif and seems to have an aesthetic end in itself: André Gides Journal, for example, or the Diario segreto Giacomo Leopardis , Charles Baudelaire's Journaux intimes , Cesare Paveses Il mestiere di vivere , Ernst Jüngers Strahlungen , Fernando Pessoas Livro do desassossego or the diaries of Friedrich Hebbel and Franz Kafka . In the Diario Segreto, Leopardi speaks of his “caro dolore”, that is, his “dear pain”, Pavese notes in his diary notes “that the first sign of pain triggers an emotion of joy, gratitude, and expectation in us”, and in Friedrich Hebbel finds the note: "Wrap the pain like a cloak". The glorification of emotional pain can also be healing.

Studies have shown that journaling can have a healing effect, especially when dealing with negative experiences. This is done by releasing hidden feelings or by allowing the writer to take a different perspective on the problem. Diary writing is also used as a therapeutic method ( writing as therapy , poetry therapy ). As a rule, no publication is sought, but the change process of the writer through the writing of his notes is in the foreground.

Publications

Well-known authors

→ This selection only contains authors whose diaries are listed in the German Wikipedia

Well-known diary writers are or were Kurt Cobain , Rudi Dutschke , Joseph von Eichendorff , Max Frisch , André Gide , Cornelia Goethe , Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , Julien Green , Carl Gustav Jung , Ernst Jünger , Franz Kafka , Walter Kempowski , Victor Klemperer , Selma Lagerlöf , Thomas Mann , Erich Mühsam , Anaïs Nin , Peter Noll , Hans Erich Nossack , Samuel Pepys , Sylvia Plath , Luise Rinser , Peter Rühmkorf , Robert Falcon Scott , Leo Tolstoi and Virginia Woolf .

Contemporary diaries from the time of National Socialism and the immediate post-war period come from Galeazzo Ciano , Anne Frank , Wladimir Gelfand , Joseph Goebbels , Alexander Hohenstein ( Franz Heinrich Bock ), Jochen Klepper , William L. Shirer and Otto Wolf .

The Austrian politician Josef Staribacher describes in his diaries in particular the reign of Federal Chancellor Bruno Kreisky .

Well-known diaries

→ This selection only contains diaries that have their own article in the German Wikipedia. The years indicate the duration.

- Emmanuel Duke von Croÿ : It has never been more wonderful to live , 1737–1784

- Michael von Faulhaber : Diaries of Michael Cardinal von Faulhaber , 1911–1952

- Selma Lagerlöf : Diary of Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf , 1932

- Victor Klemperer : I want to give testimony to the last, 1933–1945

- Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrow : One-Storey America , 1936

- Jochen Klepper : Under the shadow of your wings , 1932–1942

- Anne Frank : Diary of Anne Frank , 1942–1944

- Erich Kästner : Notabene 45 , 1945

- Max Frisch : Diary 1946–1949 , Diary 1966–1971

Fictional and literary titles

→ This selection only contains diary-like works that have their own article in the German-language Wikipedia. The year numbers indicate the year of first publication.

- Matsuo Bashō : Oku no Hosomichi , 1689

- Anders Jacobsson and Sören Olsson : Berts Katastrophen , Swedish 1987–1999, German 1990–2005

- Uwe Johnson : Anniversaries , 1970–1983

- Walter Kempowski : The echo sounder. A collective diary , 1993-2005

- Konrad Kujau : Hitler Diaries , 1983

- Lu Xun : Diary of a Madman , 1918

- Octave Mirbeau : Diary of a Chambermaid , 1900

- William L. Pierce : The Turner Diaries , 1996

- Sue Townsend : Adrian Mole , English 1982–2009

- Robert Walser : Jakob von Gunten , 1909

Diary archive

On January 14, 1998 the Association of German Diary Archives was founded. V. founded. Senders from all over Germany not only send finds from estates that go back to the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries to the German diary archive in Emmendingen . Various records from contemporaries also arrive regularly.

literature

- Peter Boerner : Diary. JB Metzlerische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1969.

- Lothar Bluhm : The Diary for the Third Reich. Evidence of inner emigration from Jochen Klepper to Ernst Jünger. Bouvier Verlag, Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-416-02294-7 .

- Donald G. Daviau (Ed.): Austrian diary writer. Edition Atelier, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-900379-88-2 .

- Arno Dusini: Diary. Possibilities of a genre. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7705-4153-7 .

- Burkhard Meyer-Sickendiek: The pain in the literary diary. In: Ders .: Affect Poetics. A cultural history of literary emotions. Würzburg 2005, pp. 424-453.

- Helmut Gold, Christiane Holm, Eva Bös, Tine Nowak: Absolutely private !? From diary to weblog. Accompanying volume to the exhibition of the same name in the Museums for Communication, Edition Braus by Wachter Verlag, Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 3-89904-310-3 .

- Eckart Henning : Differences and similarities in the structure of self-testimonies, especially diaries, autobiographies, memories and letters. In: Genealogy , 10, 1971, pp. 385-391.

- Gustav René Hocke : European diaries from four centuries. Motifs and anthology . Fischer Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-596-10883-7 .

- Ursula Kosser : The mysterious world of the diaries of not famous people. Kid Verlag Bonn 2017, ISBN 978-3-929386-67-7 .

- Volker Meid (Ed.): Sachlexikon: Literatur. Munich 2000.

- Gabriele Wilz, Elmar Brähler (ed.): Diaries in therapy and research. An application-oriented guide . Hogrefe, Göttingen u. a. 1997, ISBN 3-8017-0812-8 .

- Ralph-Rainer Wuthenow : European diaries. Character, forms, development. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-03127-X .

Web links

- Official diary - definition of the archive school Marburg, with references, 2010

- Over 80 full-text diaries from the state of Brandenburg from the years 1813-2010

- German Diary Archive eV

Individual evidence

- ↑ The History of Philosophy. Berlin: Ullstein, 1925.

- ↑ a b Thomas Steinfeld: I - a duet. Andreas Dorschel on the poetics of diary writing. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung 70 (2014), No. 89 (April 16, 2014), p. 11.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Steven E. Kagle, Early Nineteenth-Century American Diary Literature , Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1986; and Cynthia Gannett, Gender and the Journal: Diaries and Academic Discourse , Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

- ↑ Burkhard Meyer-Sickendiek : The pain in the literary diary, in: Ders .: Affektpoetik. A cultural history of literary emotions, Würzburg 2005, pp. 424–453.

- ^ Giacomo Leopardi: Memoire della mia vita, Milan 1942, p. 38.

- ↑ Cesare Pavese: The Craft of Life. Diary 1935–1950, Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 312 f.

- ^ Friedrich Hebbel: Works, fourth volume, Munich 1966, p. 566.

- ↑ Scientific American Mind , August / September 2007, p. 14 f.

- ^ Bayerische Staatsbibliothek - Digital Library, Munich Digitization Center: Summary Joseph Goebbels, diary entries about the November pogroms 1938 [Reichskristallnacht , November 10th and 11th 1938 / Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB, Munich)] .