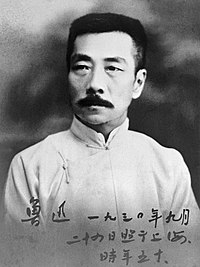

Lu Xun

Lu Xun ( Chinese 魯迅 / 鲁迅 , Pinyin Lǔ Xùn , actually Chinese 周樹 人 , Pinyin Zhōu Shùrén ; born September 25, 1881 in Shaoxing , Zhejiang Province , Imperial China ; † October 19, 1936 in Shanghai ) was a Chinese writer and intellectual of the von the Beida (Peking University) outgoing movement of the fourth May , which deals with other intellectuals at the Baihua involved movement, a reform movement for literary genre and style .

Literary meaning

Lu Xun is considered the founder of modern literature in the People's Republic of China . (In Taiwan , his works were banned for decades - until the abolition of martial law in the late 1980s.) However, the innovations not only refer to the fact that he used the slang Baihua instead of the written language Wenyan , or advocated its use, because literature, in The Baihua has been used in China since the Tang and Song dynasties . Already at the end of the 19th century, scholars such as Huang Zunxian , Qiu Tingliang and Wang Zhao advocated an increase in the prestige of literature in Baihua and the recognition of the general use of Baihua. For example, Huang Zunxian claimed, "My hand writes the way my mouth speaks".

Rather, the innovations in the literature of the May Fourth Movement, which Lu Xun co-founded, consist in the fact that it often expresses an intellectual and ideological rebellion against the elitist Confucian tradition of society. For although the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 and a Chinese republic was founded, society continued to have feudal structures in which the peasants were oppressed by the landlords . The Confucian ethics and with it the classical written language Wenyan can be considered as carriers of old ideas and ideals, not least because the government officials of the Qing Dynasty an entrance exam consist essays on topics from the had and four books had to write that with the Confucian ethics were compatible, and not popularly elected as in a democracy .

Lu Xun's short story Diary of a Crazy Man (1918) is the first and most clearly against the Confucian value system and symbolically exposes the millennia-old ethics as "ogre-eating". This anti-traditionalist thought coincided with the ideas of the intellectuals of the May Fourth Movement.

biography

The beginnings

Born in Shaoxing , Zhejiang Province , his original name was Zhou Zhangshou, but later changed his name to Zhōu Shùrén. As the son of a literary family, he was trained in the classics in his early childhood. In 1898 he studied at the Kiangnan Naval Academy in Nanking, 1899–1902 at the Institute for Mining and Railways in Nanjing ; Both schools of the western type, which catered to the thirst for knowledge of young Lu Xun better than the civil servant training. During his studies he got to know On Evolution and Ethics from Thomas Henry Huxley , which in his opinion shows the way out of China's misery.

Decision to be a writer

In 1902, Lu Xun went to Japan to study medicine. There he devoted himself more to foreign literature and philosophy and came to the conclusion that only a change in the consciousness of China can be salvation. Looking back, Lu Xun wrote about this time in 1922:

- " It had been a long time since I had seen any compatriots when a film was shown one day showing some Chinese people. One of them was tied up and many of my compatriots stood around him. They were all strong fellows, but seemed utterly The comment said that the one with the tied hands was a spy in the service of the Russians, for which the Japanese soldiers - as a warning to the others - would now cut off his head; the Chinese around him had come to the Enjoy acting.

- I had left for Tokyo before the end of the semester because after watching this film I had come to believe that medical science was not that important. I had realized that people in a weak and backward country, however strong and healthy they might be, served no other purpose than to make dull spectators or mindless objects of such public spectacle; however many of them die of illness, it would not be a misfortune. The most important thing was to change their minds, and since I thought literature was the best way to do this, I decided to start a literary movement . "

At this point, Lu Xun was writing his first political essay . In 1908 Lu Xun returned to China and taught science in Hangzhou and Shaoxing . In 1911, after the Qing Dynasty was overthrown, he became an employee of the Ministry of Education of the new Provisional Government, but then returned to teaching in Beijing.

In 1911 Lu Xun published his first short story A Childhood in China ( Huaijiu ).

In 1918 he became editor of the youth newspaper Neue Jugend . In the same year he wrote his first story Diary of a Mad Man (狂人日記, Kuangren Riji ).

Prime time

From 1918 to 1926, Lu Xun stayed in Beijing and fought with the intellectuals of the May Fourth Movement at Peking University (Beida) against imperialism and outlived traditions . He published the short story collections Call to Fight and In Search . In these collections of short stories, Lu Xun openly portrays sharp social conflicts, questions the class affiliation of the characters and seeks to realize enlightened views. The characteristic trait of the character Ah Q in The True Story of Ah Q , for example, to interpret every defeat as a moral victory, can be seen as a critical allusion to the submissive and at the same time self-satisfied policy of the Chinese government towards the imperialist aggression of Japan, especially towards the agreements of the Treaty of Versailles , in which the Chinese province of Shandong should be granted to Japan after the First World War .

The class affiliation of characters is particularly questioned in Lu Xun's short story Kong Yiji . A Confucian scholar is described who, however, only serves as an object of amusement for visitors to a wine tavern. A call for enlightenment of the common population can be read from Lu Xun's short story The Medicine . Among other things, the naive superstition is criticized that a boy suffering from tuberculosis can be cured with a bun dipped into the blood of a freshly beheaded revolutionary.

Lu Xun's commitment was also directed against the conservative circles that were re-established after 1920. He published essays in which, against the background of his own classical education, he showed that the newly formed conservative circles could not use the classical written language Wenyan themselves correctly.

In 1926, Lu Xun went to Xiamen to avoid censorship and persecution by the northern warlords . He became a professor at Xiamen University . In 1927, Lu Xun was a professor in Canton at Sun Yat-sen University . After the workers' suppression by the nationalists in Shanghai in 1927, he went to Shanghai to stand up for his captured students and stayed there until his death. He declined a nomination for the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1930 he became a member of the League of Leftist Writers . During his time in Shanghai, Lu wrote essays in which he exposed the reactionary policies of the Guomindang under Chiang Kai-shek and the imperialist aggression by Japan, which had begun with the occupation of northern China since the Manchuria crisis of 1931. He also directed his activities against conservatism in Japan.

Lu Xun died in Shanghai in 1936 .

legacy

Lu Xun's will stated:

"I had a number of things to do with my family, including the following:

- Don't take a penny for a funeral from anyone except old friends.

- Make it short, bury me, and that's it.

- Please no eulogies.

- Forget me and take care of your own life - if not, it is your own fault.

- When my son is grown up and shows no particular talents, he should have a humble job to make a living. In no case should he become a meaningless writer or artist.

- Do not rely on other people's promises.

- Do not associate with people who harm others, but at the same time reject the principle of retribution and preach tolerance. "

In 2004, the "Lu Xun Memorial Hall" was built in Shaoxing, his hometown, an important building by the architect Chen Tailing .

Poetry

Lu Xun took an ambivalent stance on poetry, because he was of the opinion that the great works of Chinese poetry had long been written:

“I believe that by the end of the Tang period , all of the great poems were written. Since then it's been better not to try your hand at writing poetry unless you 're the monkey king who can jump off the Buddha's palm. "

Still, he wrote poetry, if only out of "habit" or when asked to do a calligraphy .

Works

Collections

- Wild grasses ( 野草 , Yěcǎo )

- Morning flowers picked in the evening / flowers read in the morning in the evening ( 朝花夕拾 , Zhāohuā Xīshí )

- Call to fight / applause (呐喊 , Nàhǎn , 1922)

- In search ( 徬徨 , Páng Huáng , 1925)

- Old story retold / old freshly packed (1935)

- Brief history of Chinese novel poetry ( 中国 小說 史略 , Zhōngguó Xiǎoshuō Shǐlüè )

Stories

- From the call to fight / applause ( 呐喊 , Nàhǎn , 1922)

- Diary of a madman ( 狂人日記 , Kuángrén Rìjì , 1918)

- Kong Yiji ( 孔乙己 , Kǒng Yǐjǐ , 1919)

- The medicine / The remedy ( 藥 , Yào , 1919)

- The coming day / Tomorrow's day ( 明天 , Míngtiān , 1920)

- An insignificant incident / a bagatelle ( 一件 小事 , Yíjiàn Xiǎoshì , 1920)

- Wind and waves / Much Ado About Nothing ( 風波 , Fēngbō , 1920)

- My old home / home ( 故鄉 , Gùxiāng , 1921)

- The true story of Ah Q / The true story of the Lord Everyman ( 阿 Q 正傳 , Ā Q Zhèngzhuàn , 1921)

- The Dragon Boat Festival ( 端午節 , Duānwǔjié , 1922)

- A shimmer / a bright shine ( 白光 , Bai Guang , 1922)

- Rabbit and Cat / The Tale of the Rabbit and the Cat ( 兔 和 貓 , Tu He Mao , 1922)

- Duck Comedy / A Duck Comedy ( 鴨 的 喜劇 , Ya De Xiju , 1922)

- Opera in the village / An opera in the country ( 社 戲 , She Xi , 1922)

- From In Search / Between Times Between Worlds ( 徬徨 , Panghuang , 1925) 祝福 , Zhufu , 1924)

- In a wine tavern ( 在 酒樓 上 , Zai Jiulou Shang , 1924)

- A happy family ( 幸福 的 家庭 , Xingfu De Jiating , 1924)

- Soap / The thing with the soap ( 肥皂 , Feizao , 1924)

- The Eternal Lamp ( 長 明燈 , Chang Ming Deng , 1925); also told in China , 8 stories, selected by Andreas Donath. Fischer Bücherei, Frankfurt am Main 1967.

- The crowd as a warning / In the pillory (1925)

- The venerable scholar Gao / A scholar named Gao ( 高 老夫子 , Gao Laofuzi , 1925)

- The lonely ( 孤獨 者 , Gu Du Zhe , 1925)

- Remorse / Unwiederbringlich - The records of Juan Sheng (1925)

- Brothers ( 兄弟 , Xiongdi , 1925)

- The divorce / The divorce ( 離婚 , Li Hun , 1925)

- Mending the sky / descendants of the goddess ( 補天 , Bu Tian , 1922)

- The Flight to the Moon / The Flight to the Moon ( 奔 月 , Ben Yue , 1926)

- Combating the Flood / Conquering the Water (1935)

- Vetch collecting / Vetch (1935)

- The forging of swords / The son of the swordsmith ( 鑄 劍 , Zhu Jian , 1926)

- When leaving the pass / The journey over the pass ( 出 關 , Chu Guan , 1935)

- Resistance to aggression / Against the war of aggression (1934)

- Resurrection (1935)

Works in German and literature

German edition

- Wolfgang Kubin (Ed / Translator): Lu Xun. Work edition in 6 volumes. Zurich: Unionsverlag, 1994.

Single volumes in German

- Lu Xun - No place to write. Collected poems. Reinbek near Hamburg 1983 (translated by Egbert Baqué and Jürgen Theobaldy ). ISBN 3-499-15264-9

- Lu Xun - The Great Wall. Stories, essays, poems. Greno, Nördlingen 1987, series Die Other Bibliothek , ISBN 3-89190-226-3

- Lu Xun - Wild grasses. Publishing house for foreign language literature, Beijing 2002, ISBN 7-119-02977-0 .

- Lu Xun - morning blossoms picked in the evening. Foreign Language Literature Publishing House, Beijing 2002, ISBN 7-119-02974-6 .

- Lu Xun - In Search. Verlag für Fremdsprachige Literatur, Peking 2002, ISBN 7-119-02975-4 .

- Lu Xun - call to fight. Verlag für Fremdsprachige Literatur, Peking 2002, ISBN 7-119-02973-8 .

- Lu Xun - Old story retold. Foreign Language Literature Publishing House, Beijing 2002, ISBN 7-119-02976-2 .

Anthologies

- Lu Xun - The drunken land . Stories. Unionsverlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3293004085 .

Secondary literature

- Wolfgang Kubin (Ed.): Modern Chinese Literature. Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp, 1985.

- Leo Ou-fan Lee. Voices from the Iron House. A study of Lu Xun. Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1987.

- Raoul David Findeisen: Lu Xun. Texts, chronicles, pictures, documents. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt a. M./Basel, 2001, ISBN 3-86109-119-4 .

- Wolfgang Kubin: literature as self-redemption. Lu Xun and Vox clamantis. Chinese literature in the 20th century. In: History of Chinese Literature. Volume 7 Munich 2005 pp. 33-46.

- Gloria Davies: Lu Xun's Revolution. Writing in a Time of Violence. Harvard University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-674-07264-0 . ( Table of contents )

Individual evidence

- ^ Leo Ou-fan Lee: Lu Xun and His Legacy. University of California Press, 1985, p. XII; Fran Martin: Situating Sexualities. Queer Representation in Taiwanese Fiction, Film and Public Culture. Hong Kong University Press, 2003, p. 65; David Der-wei Wang, Carlos Rojas (Ed.): Writing Taiwan. A New Literary History. Duke University Press, 2007, p. 215.

- ↑ Culture - german.china.org.cn - Chinese Writers Who Missed the Nobel Prize. Retrieved November 27, 2019 .

- ^ Buildings that speak volumes . China Daily (2011-06-29). Retrieved October 28, 2013.

Web links

- Original texts in Chinese on Wikisource

- Literature by and about Lu Xun in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Lu Xun in the German Digital Library

- Lu Xun (1881-1936)

- Unionsverlag

- Lu Xun - Works in Six Volumes

- China: With Kung Fu against the modern classics ( Memento from September 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Confucianism as cannibalism

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lu Xun |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 鲁迅; Zhou Zhangshou; Zhōu Shùrén, 周樹 人 |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Chinese writer and leading figure in modern Chinese literature |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 25, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Shaoxing , Zhejiang Province , Chinese Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 19, 1936 |

| Place of death | Shanghai |