Classic Chinese

| Classic Chinese | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

formerly China | |

| speaker | (extinct) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) - | ( T ) - |

| ISO 639-3 | ||

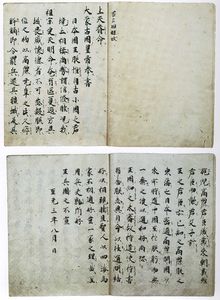

The classical Chinese ( Chinese 文言文 , Pinyin Wényánwén - "literary language"), also called "Wenyan" ( 文言 , Wenyan ) called, in the narrower sense of the written and probably spoken language of China during the Warring States Period (5th-3rd Century BC). In a broader sense, this term also includes the written Chinese language used until the 20th century.

Classical Chinese is considered the forerunner of all modern Sinitic languages and forms the last phase of Old Chinese . In general, ancient Chinese became classical Chinese from the 5th century BC onwards. Calculated; earlier forms of language are summarized under the term pre-classical Chinese . Since the Qin dynasty , Classical Chinese gradually became a dead language, but it survived as a literary language into modern times.

Lore

Classical Chinese has been handed down through countless texts. In addition to inscriptions from all times since the late period of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770–221 BC), a large number of literary texts should be mentioned, the importance of which for Chinese culture cannot be overestimated. The Confucian Four Books are of particular canonical importance ; Writings of other philosophical directions such as the Mozi and Daodejing were also created in the classical phase. Also to be mentioned are historical texts, including the Zuozhuan and other literary works, for example the "Art of War" by Sunzi . All of these works had a strong influence on the Chinese literature of later times, which justifies the preservation of classical Chinese as a literary language.

History and use

Classical Chinese is based on the spoken language of the final phase of the Zhou dynasty , the late phase of Old Chinese . After the time of the Qin dynasty , spoken Chinese increasingly moved away from classical Chinese, which - also due to the literature it was composed of, which was of immense importance for the Confucian state doctrine of later times - acquired canonical significance and was used as a written language until the beginning of the 20th century found use in literature and in official documents. Although more recent texts in classical Chinese show influences from the corresponding spoken language, all of these texts show common features that clearly differentiate them from younger forms of Chinese.

Modern Standard Chinese has been used as the written language since the 20th century , but even modern texts often contain quotes and passages in Classical Chinese, comparable to legal texts in German that contain Latin phrases. The vernacular also knows many anecdotal words ( 成語 / 成语 , chéngyǔ ), which usually consist of four morphemes and have the grammatical structures of classical Chinese.

Classical Chinese is taught in schools, but the students' competence mostly only includes reading comprehension, not writing texts. Nevertheless, reading literacy in relation to classical Chinese is also declining in the population.

Regional distribution

Dialects

Even in ancient times, the Chinese language area was divided into several varieties, which were also reflected in the written language during the classical period. Edwin G. Pulleyblank (1995) distinguishes between the following dialects:

- a dialect close to the pre-classical language

- one in Lu -based dialect, among others in the Analects of Confucius and the Book of Mencius was used

- the dialect of Chu

- a later dialect that already indicates standardization

Since the Qin dynasty, when classical Chinese increasingly became a dead language, there has been a strong standardization of the classical language, while regional differences have increased in spoken Chinese.

Spread outside of China

Not only China , but also Korea , Vietnam and Japan have the tradition of classical Chinese, whereby it should be noted that each has a different reading of the syllables of the characters. This is due to the adaptation of the adopted language development level of Chinese and its adaptation to the phonetic structure of the target language. This situation is particularly complex in Japan, where pronunciations were borrowed from Chinese at different times and thus various stages of Chinese are preserved in modern Japanese . Korean and Vietnamese have their own complete pronunciation systems. The character for example, in Korean Wenyan 文言 as muneon ( 문언 , Hanja : 文言 ) read. Is known Wenyan as Korean hanmun ( 한문 , Hanja : 漢文 ) in Japanese as Kanbun ( 漢文 ) and in Vietnamese as văn Ngôn .

font

The system of the Chinese writing of the classical period does not differ significantly from the writing of other periods: even in classical Chinese a single character (usually) stands for a single morpheme. Since the greatest change in writing in the 20th century, the official standardization and introduction of abbreviations in the People's Republic of China , Singapore and Malaysia , classical Chinese has often been written in abbreviations instead of the traditionally used traditional characters .

Phonology

Since the Chinese writing is largely independent of the sound, the phonology of ancient Chinese (Old Chinese) can only be reconstructed indirectly. It should also be noted that the pronunciation of classical Chinese changed along with the pronunciation of the spoken language. In order to understand the grammar of classical Chinese, however, the sound of the late Zhou period is mainly important. There are essentially five sources for this:

- the rhymes of Shi Jing (10th to 7th century BC) from the early Zhou dynasty

- Conclusions from the use of phonetic elements to form characters

- the Qieyun (601 AD), which arranges the signs according to initial and rhyme

- Spelling of Chinese names in foreign scripts, Chinese transcriptions of foreign names and words, Chinese loan words in foreign languages

- Comparison of modern Chinese dialects

Based on these sources, two states can be reconstructed: Old Chinese , which reflects a state that goes back a few centuries before classical times, and Middle Chinese , which is reproduced in Qieyun . These reconstructions are particularly associated with the name of Bernhard Karlgrens , who, building on the knowledge gained by Chinese scholars especially during the Qing dynasty , was the first to attempt to apply the methodology of European historical linguistics to the reconstruction of the phonology of ancient Chinese (Old Chinese) . In the meantime there have been a number of other attempts at reconstruction. While the reconstruction of Middle Chinese is essentially unproblematic, there is no generally accepted reconstruction for Old Chinese and some sinologists believe that an exact reconstruction is not even possible.

The sound inventory of Old Chinese is therefore highly controversial, but some statements can be made regarding the syllable structure. It is assumed that both the initial and final consonant clusters were possible, whereas in Middle Chinese only simple consonants were allowed in the initial and only a very limited selection of consonants in the final. It is controversial whether Old Chinese was a tonal language; however, the majority of scholars attribute the Middle Chinese tones to the action of certain ending consonants. In Central Chinese, on the other hand, there were already four tones, from which the mostly much more complex modern tone systems are derived.

For transcription

Various attempts have been made to transcribe Classical Chinese with the help of reconstructed sound forms, but due to the great uncertainty regarding the reconstruction, such an approach is questionable. Therefore, the phonetic transcription of Pinyin is used in the following , which reproduces the pronunciation of the modern high-level Chinese language Putonghua . It should be expressly pointed out that the sounds of standard Chinese are not infrequently misleading in relation to classical Chinese and obscure etymological relationships.

grammar

The following presentation of the essential grammatical structures of Classical Chinese is based on the language of the Warring States Period; the peculiarities of later texts are not discussed. The quoted sentences mostly come from classical texts of this time.

morphology

Modern Chinese is a largely isolating language that has no morphology apart from a few affixes such as the plural suffix 們 / 们 , men . Classical Chinese is also essentially isolating, but in the classical period some word formation processes that can only be found lexicalized today were probably still productive in some cases. The following table provides examples of some of the most common morphological processes:

| Basic word | Derived word | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| character | Standard Chinese | Old Chinese after Baxter 1992 ( IPA ) |

meaning | character | Standard Chinese | Old Chinese after Baxter 1992 ( IPA ) |

meaning |

| Change of the articulation type of the initial sound | |||||||

| To derive intransitive verbs from transitive verbs | |||||||

| 見 | jiàn | * kens | see | 見 / 現 | xiàn | * gens | appear |

| 囑 / 屬 | zhǔ | * tjok | to assign | 屬 | shǔ | * djok | be associated |

| Suffix * -s | |||||||

| To form nouns | |||||||

| 度 | duo | * lɐk | measure up | 度 | you | * lɐks | Measure |

| 知 | zhī | * ʈje | knowledge | 知 / 智 | zhì | * ʈjes | wisdom |

| 難 | nán | * nɐn | difficult | 難 | nàn | * nɐns | difficulty |

| 行 | xíng | * grɐŋ | go | 行 | xíng | * grɐŋs | behavior |

| To form verbs | |||||||

| 王 | wáng | * wjɐŋ | king | 王 | wàng | * wjɐŋs | to rule |

| 好 | hǎo | * xuʔ | Well | 好 | hào | * xu (ʔ) s | love |

| 惡 | è | * ʔɐk | angry | 惡 | wù | * ʔɐks | to hate |

| 雨 | yǔ | * w (r) jɐʔ | rain | 雨 | yù | * w (r) jɐ (ʔ) s | rain |

| 女 | nǚ | * ɳjɐʔ | woman | 女 | nǜ | * ɳjɐ (ʔ) s | give to wife |

| For the formation of verbs directed outside from inside verbs | |||||||

| 聞 | whom | * mun | Listen | 問 | whom | * muns | ask |

| 買 | mǎi | * mreʔ | to buy | 賣 | May | * mreʔs | to sell |

| Infix * -r- | |||||||

| 行 | hillside | * gɐŋ | line | 行 | xíng | * grɐŋ | go |

The word is monosyllabic in Classical Chinese, but partial and total duplications have resulted in new, two-syllable words which are accordingly also written with two characters: 濯濯 zhuózhuó "shiny", 螳螂 tángláng "praying mantis" to 螳 táng "mantis".

Word combinations whose overall meaning cannot be directly derived from the meanings of the components form polysyllabic lexemes: 君子 jūnzǐ “noble man” from 君 jūn “prince” and 子 zǐ “child”.

A special group is formed by monosyllabic words that are the result of a phonological fusion of two, usually “grammatical” words: 之 於 zhī-yú and 之 乎 zhī-hū> 諸 zhū; 也 乎 yě-hū> 與 yú / 邪, 耶 yé.

syntax

Parts of speech

Chinese traditionally distinguishes between two large word classes: 實 字 shízì "full words" and 虛 字 xūzì "empty words". Shizi are carriers of semantic information such as nouns and verbs ; Xuzi, on the other hand, have a predominantly grammatical function.

The differentiation of parts of speech is not easy in classical Chinese, however, since etymologically related words, which from a syntactic point of view belong to different word classes, are often neither graphically nor phonetically distinguished. So 死 sǐ stands for the verbs “to die”, “to be dead” and the nouns “death” and “dead”. This went so far that some sinologists even took the view that classical Chinese had no parts of speech at all. This is usually rejected, but uncertainties in the breakdown of parts of speech are omnipresent in Classical Chinese grammar.

Shizi

Nouns

Nouns usually serve as the subject or object of a sentence; in addition, they can also form the predicate of a sentence (see below). In some cases they also appear as verbs meaning “behave like ...” or similar, as well as adverbs : 君君, 臣 臣, 父 父, 子 子 jūn jūn, chén chén, fù fù, zǐ zǐ “The prince behaves like a prince, the minister like a minister, the father like a father, the son like a son. "

Verbs

The basic function of verbs is the predicate , as in many cases they can form a complete sentence without adding more words or particles. As in other languages, a distinction can be made between transitive and intransitive verbs in classical Chinese . Among the intransitive verbs, the state verbs , which correspond to the adjectives of other languages, form a special group. The distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs is often difficult, however, since slightly transitive verbs can be derived from intransitive verbs:

- 王 死 wáng sǐ "the king died" (intransitive) ( 王 , wáng - "king"; 死 , sǐ - "to die")

- 王 死 之 wáng sǐ zhī "the king died for him" (transitive) ( 之 , zhī - "him")

- 臣 臣 chén chén "the feudal man was a (real) feudal man" (intransitive) ( 臣 , chén - "official, feudal man, vassal; to be a feudal man")

- 君臣 之 jūn chén zhī "the prince made him a feudal man" (transitive) ( 君 , jūn - "prince"; 之 , zhī - "him")

Numeralia , which behave syntactically as verbs, are a special group of adjectives . Like verbs, they can form a predicate or an attribute and are negated with 不 , bù :

- 五年 wǔ nián "five years"

- 年 七十 nián qíshí "the years were seventy" = "it was seventy years"

Xuzi

Pronouns

The system of personal pronouns is surprisingly rich in the first and second person, but in the third person - apart from individual cases - there is no pronoun in the subject function. The third person subject pronoun is usually left out or represented by a demonstrative pronoun. As with nouns, neither genera nor numbers are distinguished in personal pronouns; this distinguishes classical Chinese from both preceding and following forms of Chinese. Overall, the following forms are mainly found:

| First person | 我 , wǒ | 吾 , wú | 余 , yú | 予 , yǔ | 朕 , zhèn | 卬 , áng |

| Second person | 爾 , ěr | 汝 , rǔ | 而 , ér | 女 , rǔ | 若 , ruò | |

| Third person | 之 , zhī | 其 , qí |

Syntactic differences in the use of these forms can be made out; outside of the third person, where 其 , qí is used as an attribute and 之 , zhī as an object of verbs and prepositions, factors such as dialect variations and the speaker's status vis-à-vis the addressee are also important.

Quasipronominalization is a special phenomenon in classical Chinese . Nouns such as first or second person pronouns are used: 臣 , chén - "I" (actually: "Lehnsmann"; Lehnsmann zum König), 王 , wáng - "here: Your Majesty" (actually: "King"), 子 , zǐ - "Herr, Sie" (actually: "Herr"; generally polite form of address).

sentence

Verbal predicates

In sentences whose predicate is a verb, the sentence position subject - verb - object (SVO) is generally found . Classical Chinese is a pro-drop language, which is why the verbal predicate is the only mandatory constituent. In addition to a subject noun phrase, certain verbs have up to two objects, both of which can occur unmarked in the postverbal position, with the direct following the indirect object:

| 天 | 與 | 之 | 天下 |

| tiān | yǔ | zhī | tiānxià |

| Sky (subject) |

give | him (indirect object) |

World (direct object) |

| "Heaven gives him the world." | |||

Prepositions, sometimes also referred to as Koverben , can appear in front of the predicate as well as after the complementary noun phrases . Where a preposition can appear is lexically conditioned:

| 王 | 立 | 於 | 沼 | 上 |

| wáng | lì | yú | zhǎo | shàng |

| king | stand | on | pond | Top |

| "The king stood over the pond." | ||||

| 得 | 國 | 常 | 於 | 喪 |

| dé | guó | cháng | yú | sāng |

| to get | country | usually | by | Bereavement |

| "You usually get the land through bereavement." | ||||

| 吾 | 以 | 此 | 知 | 勝負 | 矣 |

| wú | yǐ | cǐ | zhī | shèng fù | yǐ |

| I | Coverb "means" | this | knowledge | victory and defeat | final aspect particles |

| "With that I predict victory and defeat." | |||||

| 世子 | 自 | 楚 | 反 |

| shìzǐ | zì | Chǔ | fǎn |

| Crown Prince | Koverb "from, from" | Chu | to return |

| "The Crown Prince came back from Chu." | |||

Objects of ditransitive verbs can also be marked with prepositions. 以 yǐ can be used for the direct and 於 yú for the indirect object:

| 堯 | 以 | 天下 | 與 | 舜 |

| Yáo | yǐ | tiānxià | yǔ | Shùn |

| Yao (subject) |

by means of | World (direct object) |

give | Shun (indirect object) |

| " Yao gave the world to Shun ." | ||||

| 堯 | 讓 | 天下 | 於 | 許 由 |

| Yáo | rank | tiānxià | yú | Xǔyóu |

| Yao (subject) |

submit | World (direct object) |

to | Xuyou (Indirect Object) |

| "Yao left the world to the Xuyou." | ||||

Nominal predicates

In contrast to other historical stages of Chinese development, there is a special group of sentences in Classical Chinese in which both the subject and the predicate are noun phrases . The particle 也 yě is usually placed at the end of the sentence, but a copula is not required:

| 文王 | 我 | 師 | 也 |

| Wén Wáng | wǒ | shī | yě |

| King Wen | I mean | Teacher | Particles |

| "King Wen is my teacher." | |||

The negation takes place with the negative copula 非 , fēi , where 也 , yě can be omitted:

| 子 | 非 | 我 |

| zǐ | fēi | wǒ |

| you (quasi-pronouns) | Not be | I |

| "You are not me." | ||

Topicalization

Classical Chinese can topicalize parts of sentences by placing them at the beginning of the sentence where they can be specially marked. Particles like 者 , zhě , 則 , zé or 也 , yě are used for this :

| First part | Second part | |||||||

| 君 | 則 | 不 | 寒 | 矣 | 民 | 則 | 寒 | 矣 |

| jūn | zé | bù | hán | yǐ | min | zé | hán | yǐ |

| Quasi-pronouns "you, you" | Topicalization marker | Not | freeze | Aspect Particle | people | Topicalization marker | freeze | Aspect Particle |

| "You are not freezing, but the people are freezing." | ||||||||

| Topicalized noun phrase | Article 1 | Postscript 2 | |||||||||

| 人 | 之 | 道 | 也 | 或 | 由 | 中 | 出 | 或 | 由 | 外 | 入 |

| rén | zhī | dào | yě | huò | yóu | zhōng | chū | huò | yóu | wài | rù |

| human | Attribute particle | Away, Dao | Topicalization particles | sometimes | from | Inside | going out | sometimes | from | Outside | come in |

| "As for the Dao of man, it sometimes comes from within and sometimes from without." | |||||||||||

Aspect, mode, tense, diathesis

Grammatical categories of the verb such aspect , mode , tense , diathesis and of action remain often unmarked in all forms of Chinese. 王來 , wáng lái So can "the King is coming", "the king came," "The King is coming" "May the king come" etc. mean. Even the diathesis, the active - passive opposition, can be left unmarked: 糧食 , liáng shí - "Provision is eaten" instead of the semantically excluded "Provision eats".

However, there are also various constructions and particles , the most important of which are presented below. The aspect can be expressed in classical Chinese mainly by two particles at the end of a sentence. 矣 , yǐ seems to express a change, similar to the modern 了 , le , whereas 也 , yě rather express a general state:

| 寡人 | 之 | 病 | 病 | 矣 |

| guǎrén | zhī | bìng | bìng | yǐ |

| Our Majesty | Attribute particle | Suffer | bad | Aspect Particle |

| "The evil of Our Majesty has become worse." | ||||

| 性 | 無 | 善 | 無 | 不 | 善 | 也 |

| xìng | wú | shàn | wú | bù | shàn | yě |

| human nature | Not | be good | Not | Not | be good | Aspect Particle |

| "Human nature is neither good nor not good." | ||||||

Further distinctions between tense, aspect and mode can be marked with particles in front of the verb:

| Sentence 1 | Sentence 2 | Sentence 3 | |||||

| 將 | 之 | 楚 | 過 | 宋 | 而 | 見 | 孟子 |

| jiāng | zhī | Chǔ | guò | Song | he | jiàn | Mèngzǐ |

| Future markers | go | Chu | come round | song | and | see | Mencius |

| "When he (Duke Wen) was about to go to Chu, he passed Song and saw Mencius." | |||||||

To distinguish the passive from the active, it is often sufficient to mention the agent with the preposition Chinese 於 , pinyin yú , as the following example illustrates:

| Sentence 1 (active) |

Sentence 2 (passive) |

|||||||||

| 勞 | 心 | 者 | 治 | 人 | 勞 | 力 | 者 | 治 | 於 | 人 |

| láo | xīn | zhě | zhì | rén | láo | lì | zhě | zhì | yú | rén |

| endeavor | heart | Nominalization particles | govern | human | endeavor | force | Nominalization particles | govern | preposition | human |

| "Whoever tries with the heart rules others" | "Whoever tries hard is ruled by others" | |||||||||

In rare cases, various passive morphemes such as 見 , jiàn (actually: “see”) or 被 , bèi are used to express the passive voice : 盆 成 括 見 殺. , Pénchéng Kuò jiàn shā - "Pencheng Kuo was killed." ( 殺 , shā - "to kill").

Complex sentences

Adverbial clauses

Para- and hypotactic relationships between sentences can be left unmarked in classical Chinese:

- 不 奪 不 饜 , bù duó bù yàn - "If they do not rob, they are not satisfied.", Literally "(they) do not rob - (they) are not to be satisfied"

However, there are also various methods of marking such relationships. A very common possibility is to use the conjunction 而 , ér , which, in addition to a purely coordinating function, can also give sentences an adverbial function:

- 坐 而言 , zuò ér yán - "He spoke while he was sitting." ( 坐 , zuò - "sit"; 言 , yán - "speak")

| From 而 , ér subordinate sentence | main clause | |||

| 鳴 | 鼓 | 而 | 攻 | 之 |

| míng | gǔ | he | gong | zhī |

| sound | drum | then | attack | him |

| "Attack him while beating the drums." | ||||

Conditional clauses are particularly often marked by introducing the following main clause with the conjunction 則 , zé - "then":

| 不 | 仁 | 則 | 民 | 不 | 至 |

| bù | rén | zé | min | bù | zhì |

| Not | be human | then | people | Not | come over |

| "If you don't act humanly, the people won't come." | |||||

Complementary sentences

In Classical Chinese, complementary sentences have different forms depending on the embedding verb. After verbs like 欲 , yù “to want” and 知 , zhī “to know” there are nominalized verbs (see section “Noun phrases”), often with the aspect particle 也 , yě :

| main clause | Nominalized sentence | |||||

| 欲 | 其 | 子 | 之 | 齊 | 語 | 也 |

| yù | qí | zǐ | zhī | qí | yǔ | yě |

| want | to be (attribute pronoun) | son | (Attribute marker) | Qi | speak | (Aspect particle) |

| "He wants his son to speak in the manner of qi ." | ||||||

After other verbs, including 令 , lìng “command”, the subject of the embedded sentence appears as the object of the parent verb. This construction is also known as the Pivot Construction :

| main clause | Subject of the embedded sentence | Complementary sentence | |||

| 王 | 令 | 之 | 勿 | 攻 | 市 丘 |

| wáng | lìng | zhī | wù | gong | Shìqiū |

| king | command | them, them (object pronouns) | Not | attack | Shiqiu |

| "The king ordered them not to attack Shiqiu." | |||||

Some verbs like 可 , kě "possible," beds sets a from which an object noun phrase with the subject of the parent verb coreferential is extracted, wherein like noun phrases 所 , suǒ (see section "noun phrases") preposition stranding occurs .

| main clause | Complementary sentence | ||||

| 其 | 愚 | 不 | 可 | 及 | 也 |

| qí (attribute pronoun) | yú | bù | kě | jí | yě |

| be | stupidity | Not | to be possible | to reach | (Aspect particle) |

| "You cannot achieve your stupidity." | |||||

| main clause | Complementary sentence | ||||

| stranded preposition | embedded verb phrase | ||||

| 不 | 可 | 與 | 救 | 危 | 國 |

| bù | kě | yǔ | jiù | wēi | guó |

| Not | to be possible | With | save | to be endangered | kingdom |

| "It is not possible to save an endangered kingdom with him." | |||||

Noun phrases

In noun phrases , the head is always at the end, attributes can be marked with 之 , zhī , which stands between head and attribute:

| 王 | 之 | 諸 | 臣 |

| Wáng | zhī | zhū | chén |

| king | Particles | the different | minister |

| "The various ministers of the king" | |||

In noun phrases that do not have an overted head, the morpheme 者 , zhě is used instead of 之 , zhī :

| 三 | 家 | 者 |

| sān | jiā | zhě |

| three | family | Particles |

| "The (members) of the three families" | ||

Verbs can be nominalized by realizing their subject as an attribute and they as the head of a noun phrase:

- 王 來 , wáng lái - "the king is coming"> 王 之 來 , wáng zhī lái - "the coming of the king; the fact that the king is coming "( 王 , wáng -" king "; 來 , lái -" coming ")

Conversely, the predicate can also be used as an attribute, creating constructions that correspond in their function to relative clauses :

- 王 來 , wáng lái - "the king is coming"> 來 之 王 , lái zhī wáng - "the coming king" (literally: "the king of the coming")

者 , zhě can then also be used in the same functions :

- 來 者 , lái zhě - "the one who comes"

| 知 | 者 | 不 | 言 |

| zhī | zhě | bù | yán |

| knowledge | Particles | Not | speak |

| "Who knows, he doesn't speak" | |||

Relative clauses whose external reference word is co-indexed with an object of a verb or a coverb embedded in the relative clause can be formed with the particle 所 , suǒ . (For the syntax of this quote, see the section on nominal predicates ):

| 所 | 得 | 非 | 所 | 求 | 也 |

| suǒ | dé | fēi | suǒ | qiú | yě |

| Particles | to get | Not | Particles | search | Aspect Particle |

| "What (you) got" | "What (one) was looking for" | ||||

| "What (you) got is not what (you) were looking for." | |||||

With the exception of 於 , yú , prepositions come directly after 所 , suǒ when their complement is extracted. The agent of the embedded verb can appear as an attribute in front of the 所 , suǒ -phrase.

| 亂 | 之 | 所 | 自 | 起 |

| luàn | zhī | suǒ | zì | qǐ |

| disarray | Attribute particle | Particles | from | get up |

| "Where the disorder comes from" | ||||

Dictionary

The lexicon of classical Chinese differs significantly from that of modern Chinese. In quantitative terms, Classical Chinese of the Warring States' era only includes around 2000 to 3000 lexemes, plus a large number of person and place names. In addition to the word material inherited from Proto-Sino- Tibetan and the word material already borrowed from neighboring languages in the pre-classical period, words were also borrowed from non-Chinese languages in the classical period. The word 狗 gǒu "dog", which appeared for the first time in the classical period and later replaced the old word 犬 quǎn "dog", was probably adopted from an early form of the Hmong-Mien languages native to the south of China . After the Qin dynasty, the vocabulary of classical Chinese increased considerably, on the one hand through the inclusion of loan words, but also through the adoption of words from the spoken language.

Individual evidence

- ↑ This effect is also attributed to a nasal or glottal prefix, see e.g. Sagart 1999, pp. 74–78.

- ^ Lunyu 12/11

- ↑ Mencius 5A / 5

- ↑ Mencius 1A / 2

- ↑ Guoyu

- ↑ Sunzi , Bingfa 1/2/6

- ↑ Mencius 3A / 1

- ↑ Mencius 5A / 5

- ↑ Zhuangzi 1.2.1

- ↑ Mencius 3A / 1

- ↑ Zhuangzi 7/17/3

- ↑ Xinxu Cishe 6

- ↑ Guodian Yucong 1.9, quoted from Thesaurus Linguae Sericae ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Yanzi Chunqiu 1/12/1

- ↑ Mencius 6A / 6

- ↑ Mencius 3A / 1

- ↑ Mencius 3A / 4

- ↑ Mencius 7B / 29

- ↑ Mencius 1A / 1

- ↑ Mencius 2B / 11

- ↑ Lunyu 11.17

- ↑ Guoyu 2/15

- ↑ Mencius 3B / 6

- ↑ Zhanguoce 26/11/2, quoted from Thesaurus Linguae Sericae ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Lunyu 05.21

- ↑ Han Feizi 27/4

- ↑ Mencius 1A / 7

- ^ Lunyu 3/2

- ↑ Daodejing 56/1

- ↑ Mao Commentary on Shi Jing 43

- ^ Mozi 4/1

literature

General

- Wang Li (王力): “Sketch of the History of Chinese” (汉语 史稿), Beijing 1957.

- Zhou Fagao (周 法 高): "Grammar of Old Chinese" (中國 古代 語法), Taipei, 1959–1962

- Zhu Xing (朱 星): "Old Chinese" (古代 汉语), Tianjin Renmin Chubanshe, Tianjin 1980.

Grammars

- Georg von der Gabelentz : Chinese grammar with exclusion of the lower style and today's colloquial language . Weigel, Leipzig 1881, digitized . Reprints: VEB Niemeyer, Halle 1960; German Science Publishing House, Berlin 1953.

- Robert H. Gassmann: Basic structures of the ancient Chinese syntax . An explanatory grammar (= Swiss Asian Studies. 26). Peter Lang, Bern 1997, ISBN 3-906757-24-2 .

- Derek Herforth: A sketch of Late Zhou Chinese grammar . In: Graham Thurgood and Randy J. LaPolla (Eds.): The Sino-Tibetan Languages . Routledge, London 2003, ISBN 0-7007-1129-5 , pp. 59-71 .

- Ma Zhong (马忠): "Ancient Chinese Grammar" (古代 汉语 语法), Shandong Jiaoyu Chubanshe, Jinan 1983.

- Edwin G. Pulleyblank: Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver 1995, ISBN 0-7748-0505-6 / ISBN 0-7748-0541-2 .

- Yang Bojun (杨伯峻) and He Leshi (何乐士): “The grammar and development of Old Chinese” (古 汉语 语法 及其 发展), Yuwen Chubanshe, Beijing 2001.

- Yi Mengchun (易 孟 醇): "Grammar of Chinese before the Qin Dynasty" (先秦 语法), Hunan Jiaoyu Chubanshe, Changsha 1989.

Textbooks

- Gregory Chiang: Language of the Dragon. A classical Chinese reader. Zheng & Zui Co., Boston, MA 1998, ISBN 0-88727-298-3 .

- Michael A. Fuller: An Introduction to Literary Chinese . Harvard Univ. Asia Center, Cambridge et al., 2004, ISBN 0-674-01726-9 .

- Robert H. Gassmann, Wolfgang Behr: Antique Chinese . Part 1: A preparatory introduction to five element (ar) courses. Part 2: 30 texts with glossaries and grammar notes. Part 3: Grammar of Ancient Chinese. (= Swiss Asian Studies. 18). Peter Lang, Bern 2005, ISBN 3-03910-843-3 .

- Paul Rouzer: A New Practical Primer of Literary Chinese . Harvard Univ. Asia Center, Cambridge et al., 2007, ISBN 978-0-674-02270-6 .

- Harold Shadick, Ch'iao Chien [Jian Qiao]: A First Course in Literary Chinese , 3 Volumes. Ithaca, Cornell University Press 1968, ISBN 0-8014-9837-6 , ISBN 0-8014-9838-4 , ISBN 0-8014-9839-2 . (Used as a textbook at several universities in German-speaking countries.)

- Ulrich Unger : Introduction to Classical Chinese . (2 volumes) Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1985, ISBN 3-447-02564-6 .

Phonology

- William H. Baxter: A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and monographs No. 64 Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, ISBN 3-11-012324-X .

- Bernhard Karlgren : Grammata serica recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm 1957 (of historical interest)

- Edwin G. Pulleyblank: Lexicon of reconstructed pronunciation in early Middle Chinese, late Middle Chinese, and early Mandarin. UBC Press, Vancouver 1991, ISBN 0-7748-0366-5 (most modern reconstruction of Central Chinese)

- Laurent Sagart: The roots of Old Chinese (= Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 184). Mouton de Gruyter, Amsterdam 1999, ISBN 90-272-3690-9 , ISBN 1-55619-961-9 .

Dictionaries

- Seraphin Couvreur: Dictionnaire classique de la langue chinoise Imprimerie de la mission catholique, Ho Kien fu 1911.

- Herbert Giles : Chinese-English dictionary Kelly & Walsh, Shanghai 1912

- Wang Li (王力), Ed .: “Wang Li's Dictionary of Old Chinese” (王力 古 汉语 字典), Zhonghua Shuju (中华书局), Beijing 2000. ISBN 9787101012194

- Robert Henry Mathews: Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary China Inland Mission, Shanghai 1931. (Reprints: Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1943 etc.)

- Instituts Ricci (ed.): Le Grand Dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise Desclée de Brouwer, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-220-04667-2 . See Le Grand Ricci .

- Werner Rüdenberg, Hans Otto Heinrich Stange: Chinese-German dictionary. Cram, de Gruyter & Co., Hamburg 1963.

- Ulrich Unger: Glossary of Classical Chinese . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-447-02905-6 (In contrast to the other dictionaries mentioned here, limited to the Warring States period)

- “Dictionary of Old Chinese” (古代 汉语 词典), 3rd edition, Shangwu Yinshuguan (商务印书馆), Beijing 2014. ISBN 978-7-100-09980-6