Zhuangzi

Zhuāngzǐ ( Chinese 莊子 / 庄子 , W.-G. Chuang-tzu ; * around 365 BC; † 290 BC ) means "Master Zhuang". His personal name was Zhuāng Zhōu ( 莊周 / 庄周 ). Zhuangzi was a Chinese philosopher and poet . A famous work, partly by his hand, is also called "Zhuangzi" . In the course of the veneration of Zhuang Zhou as a Daoist saint in 742 under Emperor Xuanzong, it was also given the honorary title "The true book of the southern blossom country " ( 南華 眞 經 / 南华 真经 , Nánhuā zhēnjīng , abbreviated 南華 經 / 南华 经 , Nánhuājīng ) . Together with the Daodejing it is considered to be the main work of Daoism , although a Daoist institution at the time of the Zhuangzi cannot be proven. The writing is considered to be one of the most beautiful, most interesting and most difficult in Chinese intellectual history.

In Kiautschou , leased from Germany , the name was written as Dschuang Dsï according to the Lessing-Othmer system , the simplified version of which, Dschuang Dsi, became popular thanks to Richard Wilhelm's translation from 1912. The also outdated transcription according to the Stange system is Tschuang-tse .

Life

As with almost all of his contemporaries, Zhuangzi's biographical data are only fragmentary and unsecured. The essential information comes from Sima Qian (approx. 145–90 BC). According to his work Shiji (chap. 63), Zhuangzi held an office for a time in the " lacquer garden " ( 漆 園 / 漆 园 , Qīyuán ), which belonged to the city of Meng ( 蒙 , today Anhui) in the state of Song :

“Zhuangzi was a man from Meng (now Anhui), his nickname was Zhou. He held an office in the lacquer garden (Qiyuan) in Meng and was a contemporary of King Hui of Liang (r. 369-335) and King Xuan of Qi (r. 369-301). There was no area in which he did not know his way around, but mainly he referred to the sayings of Laozi . He wrote a book with more than 100,000 words, most of which are parables. He wrote The Old Fisherman, Robber Zhi, and Breaking Open Boxes to ridicule Confucius' followers and explain the doctrine of Laozi. The »Wastes of Weilei« and »Kangsangzi« belong to the invented stories without reference to reality. He was a gifted poet and word artist, described facts and discovered connections; he used all of this to expose the Confucians and Mohists , even the greatest scholars of his time, were unable to refute him. The words flowed and gushed out of him and suddenly hit the core. Therefore, neither the kings and princes nor other great men succeeded in binding him to them. When King Wei of Chu heard of Zhuangzi’s talent, he sent a messenger with rich gifts to entice him to become a minister. Zhuangzi smiled and said to the messenger from Chu: “A thousand gold pieces, what a high salary; a ministerial post, what an honor! Are you the only one who hasn't seen a sacrificial cattle outside the city? It is first fattened, then with ornaments embroidered [blankets] are thrown over it in order to lead it inside the temple, there it can still very much wish to transform itself into a lonely piglet - will this be granted to it? Get out of here, briskly, and don't sully me! I would rather roam about peacefully and roll around in a disgustingly stinking puddle of mud than let the customs at court restrain me; I will not hold office until the end of my life, but will follow my will. ""

With the exception of a guard in a lacquer garden ( Qiyuan ), Zhuangzi probably refused to accept any office. An attitude that is already expressed in the first chapter: When the holy ruler Yao - one of the most important figures in Chinese tradition - offers 'approvers' to lead the empire, he replies:

"Freigeber said:" You have arranged the empire. Since the kingdom is already in order, I would only do it for the sake of the name if I wanted to replace you. The name is the guest of reality. Should I perhaps take the position of a guest? The wren builds his nest in the deep forest, and yet he only needs one branch. The mole drinks in the great river, and yet it only needs so much to quench its thirst. Go home! Let it go, O Lord! I have nothing to do with the Reich. "

The highest honor is denied here with the reference to the simplest physical needs: Just as the mole only drinks as much as he is thirsty, 'approvers' are also satisfied when they have a full stomach. Since Zhuangzi acted accordingly in real life, his family was often poor.

Zhuangzi was married and had contact with various other philosophers and philosophy schools. He is said to have been the student of Tian Zifang . In the book of Zhuangzi, the entire 21st chapter has the name "Tian Zifang" as the heading. According to this, Tian Zifang was a student of Dongguo Shunzi ( 東 郭順子 / 东 郭顺子 ), who in turn met Zhuangzi a few passages later and was instructed by him. This makes it unlikely that Zhuangzi was both Tian Zifang's student and Dongguo Shunzi's teacher. Christoph Harbsmeier suspects that Hui Shi , also called Huizi 惠子 (master friendliness) (380-305 B.C.E.), a sophist from the 'school of names' (mingjia) was the master or mentor of Zhuangzi. In Section 13.1, Zhuangzi describes his teacher abstractly, without naming any person:

“My teacher, my teacher! He [observes] the innumerable living beings closely, without judging; He meets countless generations benevolently, but not out of humanity; he is older than antiquity but does not emphasize his age; he spans the sky, carries the earth, shapes the shape of numerous living beings, but does not consider himself to be the creator - that is natural joy ... "

In Zhuangzi's writings there are also Confucian traits scattered around, especially the spring and autumn annals are mentioned with caution. Compared to other historical figures, it is noticeable that Zhuangzi is usually portrayed in a very human way, without any idealization, as is the case with Laozi, for example . Some passages of the book Zhuangzi tell of some students or followers who apparently followed Zhuangzi during his lifetime. In section 20.1 he walks in the mountains and debates with his students which goose should be slaughtered, the cackling or the silent one. In chapter 32.16, his disciples gather around him, as it appears that he will die; they want to honor him with a great funeral, but he refuses.

The historical truthfulness of the anecdotes in Zhuangzi about the person Zhuangzi can be questioned. Sima Qian's records were made nearly two hundred years after Zhuangzi’s death, and no written testimony of him has survived since then. Nevertheless, the skepticism about the historicity of the person Zhuangzi should not go so far as to completely deny his existence or to consider all anecdotes about his life to be fabricated.

Work and text

The book “Zhuangzi” is a collection of texts, the authorship of which is partly unclear. It is generally believed that only the first seven chapters are ascribed to the person Zhuangzi; the other chapters may have been compiled by followers of his school. Richard Wilhelm gives a useful overview of these first seven chapters from the standpoint of Daoism as philosophy in his 1925 commentary "Die Lehren des Laotse" (contained in: R. Wilhelm, "Laotse. Tao te king. The book of the way of life") , Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach, 2nd edition: January 2003):

“… Dschuang Dsi not only gives us Taoist wisdom, but also a correct Taoist philosophy. Its philosophical foundations can be found in the first 7 books, the so-called inner section. ...

The first book is called "Hiking in Leisure". It forms the exposure of the whole. Earthly life with its fates and influences is compared to a little quail ... while life in blissful leisure is free from all pettiness. It is compared to the monstrous P'ong bird, whose wings soar through the sky like hanging clouds. ...

Of particular importance is the second book, "The Balance of World Views". Here the solution to the philosophical issues of the time is given from the Taoist point of view. ... Following the Tao teking, Dschuang Dsi recognized all these opposing views, which are in logical disputes, in their necessary conditionality. Since neither side could prove their right, Dschuang Dsi found the way out of the disputation to intuition, ...

In the third book comes the practical application of this knowledge. It is important to find the master of life, not to strive for any particular individual situation, but to pursue the main arteries of life and to come to terms with the external position in which one finds oneself; because it is not a change in the external conditions that can save us, but a different attitude to the respective living conditions from the Tao. This gives access to the world that is beyond differences.

In the fourth book the scene leads out of the individual life into the human world. ... Here, too, it is important to maintain the all-encompassing point of view, not to bind yourself - into any isolation. Because the isolation gives usability, but it is precisely this usability that is the reason that one is used. One is tied into the context of the phenomena, one becomes a wheel in the great social machine, but precisely because of this one becomes a professional and one-sided specialist, while the "useless" person who stands above opposites saves his life through this.

The fifth book is about the "seal of full life." It shows through various parables how the inner contact with the Tao, which gives true unintentional life, exercises an inner influence over people, before which any external inadequacy must disappear. It is the stories of cripples and people of monstrous ugliness through which this truth is most clearly revealed precisely because of the paradox of external conditions.

The sixth is one of the most important books of Dschuang Dsi: "The great ancestor and master". It deals with the problem of the person who has found access to the great ancestor and master, the Tao. “Real people weren't afraid to be lonely. They did not perform any exploits, they did not make plans. ... They did not know the joy of life or the aversion to death. ... They came calmly, they went calmly. ... "

The seventh book" For the use of kings and princes "concludes and deals with ruling through non-ruling. “The highest man,” it says, “uses his heart like a mirror. He does not go after things and does not go to meet them. He reflects them, but he doesn't hold onto them. ""

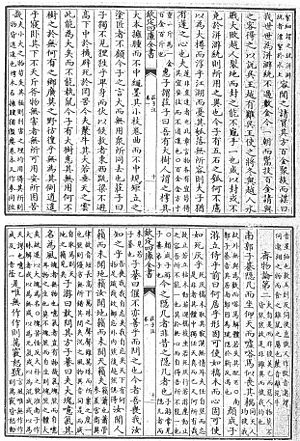

The current version of the text comes from the philosopher Guo Xiang (253-312) from the Western Jin Dynasty , so it is a few hundred years younger than the original text written by Zhuangzi. Guo Xiang has revised and shortened the text; the Hanshu literature catalog still mentions a version of 52 chapters ( pian ). Guo Xiang also wrote the first commentary on the book “Zhuangzi” , which had a considerable influence on further reception.

Today's text version is divided into three parts:

- neipian(内 篇): the inner chapters (1–7), which were written by Zhuangzi himself,

- waipian(外 篇): the outer chapters (8–22) and

- zapian(杂 篇): the mixed scriptures (23–33).

Only the authorship of the inner chapters is undisputed. Some external ones (XVII-XXII are possible) can also be considered authentic. For a full understanding of the inner chapters, however, the connection with sections of the outer chapters must also be established. Even if it is wrong from a text-critical point of view, most traditional commentators and also today's philosophers use the entire text as a basis for the development of the content. (Nonetheless, the following is identified: When "Zhuangzi" is spoken of, then the person and the text of the inner chapters are meant. Parts of the outer chapters are referred to by referring to the book "Zhuangzi" ". )

The chapters whose authorship is unclear can be assigned to different schools:

- Zhuangzi himself (I-VII) or direct pupil (XVII-XXII, 4th century BC)

- "Primitivists" influenced by Daodejing, possibly belonging to the nongjia direction (VIII-XI, approx. 205 BC)

- " Syncretists " possibly successors of Liu An von Huai-nan (XII-XVI, possibly XXXIII, approx. 130 BC)

- "Individualists" around Yang Zhu (XXVIII-XXXI, approx. 200 BC)

The formal text form of the “Zhuangzi” is characterized by a complexity of content and style for ancient China and poetic tricks. Some passages are written in rhyme form. The language of the work points to a tradition that has otherwise not been handed down, which was probably alive in the south of China in the State of Song. In contrast to Laozi, Zhuangzi dresses his opinions and findings in artfully formulated parables , short treatises on philosophical problems and anecdotal dialogues and stories. As a result, the number of words to which the status of a technical term can be assigned is quite small. Some are taken from the Confucian tradition.

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Chinese term | Transcription | meaning |

| 天 | tiān | sky |

| 德 | dé | Virtue |

| 道 | dào | path |

| 氣 | qì | Life force, breath |

| 精 | jīng | Essence, seed, state of mind, chi state |

| 神 | shén | Spirit (of the dead), state of mind |

| 心 | xīn | heart |

| 君子 | jūnzǐ | Noble (Confucius) |

| 賢人 / 贤人 | xiánrén | the virtuous / knower (Confucius) |

| 聖人 / 圣人 | shèngrén | the saint / wise (Confucius) |

| 真人 | zhēnrén | the real / authentic person * |

| 至人 | zhìrén | the perfect * |

| 神 人 | shénren | the spiritual man * |

| * Zhuangzi's ideal of man. The three terms are usually used synonymously. | ||

Teaching

introduction

Intellectual and political environment

Zhuangzi lived in a time of great political and spiritual upheaval. During this time of the Warring States , various princes fought for supremacy, the old traditions and rites were no longer maintained with the previous seriousness and trust in the supreme deity, heaven ( 天 , tiān ), was dwindling, although Confucius himself had striven for a renewal and Mencius expanded heaven to the abstract supreme principle of Confucian philosophy. At the same time a large number of other philosophical schools emerged, which fought against each other, which is why one speaks of the time of the hundred schools .

One can assume that forms and approaches that are similar to Daoist thought already existed at the time of the person of Zhuangzi and that Zhuangzi was linked to him, although the work of Zhuangzi together with the Laozi is the earliest written source.

Position on Confucianism

The most important philosophical school at the time of Zhuangzi was Confucianism . Zhuangzi used his precise knowledge of this above all for sharp and pointed criticism, so he devised humorous encounters between Confucius and Laozi, which make the Confucians' conventionalism and ceremonialism appear exaggerated.

Many of the stories boast of uselessness and show a rejection of Confucian self-cultivation. In addition, in many places the Confucians with their rules and regulations are made responsible for the deplorable state of the world. The criticism of civilization and culture that appeared in the “Zhuangzi” became an essential element of the Chinese intellectual world, and the retreat into idyllic nature praised in the “Zhuangzi” exerted a strong influence on the Chinese educated class.

Zhuangzi did not reject the cultural forms, customs , customs and patterns of perception in principle, but tried to achieve flexibility and spontaneity towards them, so that he was no longer subject to given patterns of interpretation. He saw the mistake of the Confucians in forgetting that decency and morals were established by themselves. If the human origin is forgotten, then the individual is at the mercy of the rigid rules of coexistence, which no longer merely serve to promote togetherness, but rather restrict the individual and deprive him of his spontaneity.

Zhuangzi pointed out that people of bygone ages still had an original relation to law and custom: “In the law they [the true people of antiquity] saw the essence of the state, in the manners a facilitation of communication, in the knowledge the requirements of the time , in the spiritual influence the means to draw people to oneself. "

Zhuangzi contrasted the ideal of the Confucians (the noble ) with that of the holy or true man ( Zhenren ). The latter is opposed to social demands with a discretionary distance, with the same ease that "the ancients" still had against law , custom, knowledge and influence when these were not yet developed into imperatives by the Confucians .

However, Zhuangzi did not criticize the teacher Confucius, who himself pointed out that it is important not to slavishly submit to the rules (rather to decide according to the situation and context ), but rather his students, who stare at the living teaching of Confucius Confucianism ism ossified. In the eyes of Zhuangzi, all that remained was an empty formalism that had lost its original relationship to its own nature:

“If you step on someone's foot in the crowd, you apologize for their carelessness. If an older brother steps on his younger brother's foot, he pats him on the shoulder. If the parents do it, nothing else happens. That is why it is said: the utmost courtesy does not show any special consideration for people; highest justice does not care about individual things; highest wisdom does not make plans; highest love knows no affection, highest loyalty gives no pledge ... "

So Zhuangzi did not assert an immorality against Confucius, but what he believed to be the true and original morality between people.

Opening of the "Zhuangzi"

The opening story of the "Zhuangzi" is about the bird pong (Richard Wilhelm translates as " Rokh ", where he notes with a footnote that the Chinese word is "pong") and the quail. Both beings are caught up in the world of things, the realm in which everything is subject to relativity:

“His back (sc. Pong) resembles the Great Mountain; its wings are like clouds hanging from the sky. In the hurricane he climbs up in circles, many thousands of miles to where the clouds and air come to an end and he only has the blue-black sky above him. Then he goes south and flies to the southern ocean.

A fluttering quail laughed at him and said, “Where is he going? I soar up and barely cross a few fathoms, then I let myself down again. When you flutter around in the thicket, that is already the highest achievement in flying. But where is it going? ""

The quail's knowledge corresponds to that of ordinary people: what is bigger than them they call big, what is smaller than them they call small. What their surroundings consider right they call right, what their surroundings think wrong they call wrong. It is true that the large bird, when it soars, has a significantly higher perspective than the quail, which scoffs at it from its limited views, but in order to reach the appropriate height it is bound to its size and weight. Both positions, that of the quail - the uneducated person - but also the higher-lying perspective of the well-informed, appear to Zhuangzi to be wrong, because both remain dependent: the quail is limited because it only knows the thicket and only flies a few steps, but also the big bird relies on a lot of wind to lift its weight up. Since they are dependent on something, both remain in the world of things, they remain bound to something for their knowledge, their knowledge is only relative.

The dependency of both arises from the fact that their knowledge is based only on sensual experience. However, empirical knowledge can only be accumulated in a certain amount, depending on the effort it is that of a quail or the bird's pong. Zhuangzi, on the other hand, does not focus on individual objects of knowledge, but rather the cosmos as a unified whole and its eternal change. In relation to this, Zhuangzi sought to develop a thinking that is no longer dependent on anything, a position beyond limited relativity.

- Traditional reading

The corresponding section was traditionally understood differently by some Chinese interpreters, which goes back to the influential commentary by Guo Xiang († 312) and whose position Fung Yu-Lan still takes up. They are of the opinion that by contrasting both positions, the large and the small, Zhuangzi wants to make it clear that it is best for the happiness of each individual if he remains in his dimension. For this purpose, reference is made in particular to the similar history of the turtle.

Zhuangzi describes the highest man in Book II, Section 8 with great clarity. Therefore, Richard Wilhelm compares the great bird with the "superman who is called the highest man, spiritual man and called saint". This view is also supported by the beginning of Book II, Section 2, which Wilhelm reproduces in rhyming form. Eva Wong renders this part along with Section 1 of Book 2 as follows: "Great understanding is comprehensive, and small understanding is delicate. Great words carry strength and small words are insignificant and quarrelsome." Evidence for this view can also be found at Burton Watson. In Book II, Section 3 of the Liezi , it is clearly pointed out that "flying on the wind" requires previous efforts and renunciation. In Book I, Section 1, Zhuangzi points out that Liezi was completely independent of the pursuit of happiness, but that he was still dependent on things outside of himself (the wind that carried him). But the position of independence from things and the change in the limitless is a purely subjective experience and cannot be communicated to others, just as it cannot liberate a person comprehensively from the things of life even during the life span of a person. However, it can lead to the in itself insignificant ephemeral things of everyday life no longer paying attention (in contrast to the quail), because one has the reality (the work, the work) of the limitlessness of time (change) and space (emptiness) recognized.

"Within the mystical direction, two types can be distinguished. One type is passive surrender to the great one. This type is the predominant one in Christian mysticism. The other type is that of the magician, who soars into the hereafter on his own The deity appropriates. This type is most impressively represented by Heraclitus. There is no doubt that Juang Dsï belongs to this latter, active type of mysticism. Some of his figures, such as the Comprehensive, Book XI, 3, point directly to It is the mysticism of upswing, not sinking, that we find in Dschuang Dsï, and so it is no wonder that at the top of the whole work is the parable of the bird Rokh, whose flight around the world symbolizes the energy of this upswing . " Richard Wilhelm, Introduction to Dschuang Dsï

The great importance that Zhuangzi placed on respecting the characteristics of the individual explains his aversion to institutions and political regulations: These establish binding and general values and norms of behavior, which then override individual characteristics and needs and people at the same time encourage them to be zealous for them. However, the efforts to achieve it only lead to deviating from the Dao, the path, and no longer conforming to one's own De. Accordingly, Zhuangzi's idea of a government is not shaped by a catalog of measures and laws, but his ideal is non-action ( 無爲 / 无为 , wúwéi ).

Eternal change

A position of relativity is not subject any more, so the gene of quail or the effort of the bird Pong is not in the world of things specific to something bind leave. What Zhuangzi is looking for is an unbound view, a free attitude towards things and an attitude with which one can “wander at leisure” through the world - so the title of the first book.

Now things and the world are not just there for Zhuangzi, they are in eternal change. All things are subject to a constant flow within which they mutually affect one another :

“The edges of the shadow asked the shadow and said:“ Soon you are stooped, now you are upright; soon you are disheveled, soon you are combed; soon you sit, soon you get up; soon you run, soon you stop. How does that work? "The shadow said:" Dude, dude, how do you ask superficially! I am, but don't know why I am. I am like the empty shell of the cicada, like the stripped skin of the snake. I look like something but I am not. I'm strong in the firelight and by day. In sunless places and at night I fade. I am dependent on the other there (the body), just as he depends on another. If he comes, I'll come with him. If he goes, I'll go with him. If he is strong and powerful, then I am strong and powerful with him. Am I strong and powerful, what else do I need to ask? ""

Within the material world, it is pointless to ask for a final reason that sets everything in motion: As the shadow notes, this is a superficial question, because it only leads to the conditional, since everything that is in the eternal round of things is involved. It also seems nonsensical to rebel against conditionality, because it cannot be shaken off because it is what makes the world into the world, the shadow into the shadow. But change is not only limited to the world of things, it also affects human opinions and feelings:

“Li von Li was the daughter of the Ai border guard. When the Prince of Dzin had only just taken her, she wept bitterly, so that the tears wet her robe. But when she came to the king's palace and became the king's companion, she regretted her tears. "

Now the question arises how to deal with the eternal change of things. Probably the best-known parable from the Zhuangzi is the so-called "butterfly dream":

| 昔者 莊周 夢 為 胡蝶 , 栩栩 然 胡蝶 也 , 自喻 適 志 與! 不知 周 也。 俄 然 覺 , 則 蘧 蘧 蘧 然 周 也。 不知 周 周 之 夢 為 胡蝶 與 , 胡蝶 之 夢 為 周 與 胡蝶 , 周 與必有 分 矣。 此之謂 物化。 | “Dschuang Dschou once dreamed that he was a butterfly, a fluttering butterfly that felt comfortable and happy and knew nothing about Dschuang Dschou. Suddenly he woke up: there he was really and truly Dschuang Dschou again. Now I don't know whether Dschuang Dschou dreamed that he was a butterfly or whether the butterfly dreamed that he was Dschuang Dschou, although there is certainly a difference between Dschuang Dschou and the butterfly. So it is with the change of things. " |

Obviously the changing world shows itself from different viewpoints in different light, but for Zhuangzi it is not important which of these viewpoints is preferable, because every viewpoint you take is equally true, whether you are a butterfly or a person. Because of eternal change, there is no particularly excellent point of view - at least none in the middle of the world of things . The world cannot be explained by a single principle or law, there is no solid ground from which one can gain philosophical certainty about things. Both perspectives can be clearly distinguished , but their position on the truth is equally important.

| In Chinese texts of the time, there is no clear distinction between whether the statement made relates only to how things appear to us ( epistemological questioning), or whether it means how things are ( ontological questioning). Therefore - at least for the inner chapters - it is not possible to clearly distinguish between the Dao as "alone experience" and "world principle". |

So what Zhuangzi taught was not a perspectivism that emphasizes the relativity of all possible consideration. Rather, the wisdom of the “holy man” consists in the fact that he can temporarily take up possible perspectives without being bound to them. He switches between them as the situation suggests. This mental agility is expressed in the change from humans to butterflies. It takes place with ease like the transition between sleeping and waking.

For Zhuangzi, the Dao ( 道 in English "way") was this eternal change of things. The wisdom of the saints consists in recognizing the Dao and following it, i.e. the change of things. This makes it understandable what the opening story of the “Zhuangzi” aimed at: The two positions - inscribed inner limitation, the tightness of the quail and the sluggish nature of the large bird - are overcome by looking at eternal change: Whoever is not bound by either of the two positions , acquire the freedom of the saints who are able to see things in the light of change.

Daoist mysticism

Zhuangzi is considered a Daoist mystic and has strongly influenced this tradition. Zhuangzi is connected to the Daoist tradition in particular through the concept of the sacred, the zhenren. The Zhenren at Zhuangzi is intertwined with the belief in immortals ( Xian ), human-shaped, immortal beings who have supernatural powers. Zhuangzi is considered the oldest source for describing these sacred beings.

The saint in Zhuangzi experiences complete freedom of body and mind. Thus he also stands beyond the worldly. The saint travels and roams through the universe with which he experiences a unity. He does not subordinate himself to any norms and makes diversity without limits his own. The saint therefore has an all-encompassing ability to change, but at the same time his identity is unified and unifying. The saint is free from worries, including political, moral or social. Likewise, he is not metaphysically in uncertainty. He does not strive for effectiveness, has no internal or external conflicts, does not suffer from want and does not seek anything. Free spiritually, he has a perfect union with himself and everything that exists. It is of perfect fullness and completeness and has a cosmic dimension. In contrast to the Shengren of Daodejing, the Zhenren of Zhuangzi does not rule. Attributes that are most often assigned to the Zhenren in the Zhuangzi are you , in the sense of unique, alone and real, as well as tian , heavenly, which is in contrast to human and thus also means natural.

In the first chapters of the Zhuangzi, the saint is described as follows: He rides the wind and white clouds, he does not decompose, he does not burn in fire or drown in water, embers and frost do not touch him, humans and animals can do him do nothing.

This description of the saint is one of the earliest testimonies of what later hagiographies of Daoist saints make up. Likewise, details are already presented in the Zhuangzi, which prove the longevity techniques of this time: Divine people do not consume grain (a Daoist diet), breathe the wind, drink dew, divine people fly on clouds and in the air, they ride flying kites and can walk beyond the seas.

In these and other passages of the text, there is an allusion to another characteristic of Daoism, the mystical flight (cf. Liezi ). The book of Zhuangzi begins with the flight of the giant phoenix, suggesting that this flight is a topic of importance and an indication of Zhuangzi's intention. In several passages of text, Zhuangzi's characters fall into an ecstatic state and leave their body behind, “like dead wood”, and their heart, which is also considered the spirit and intellect, as “extinguished ashes”.

The mystical element of Daoism already emerges in the Zhuangzi, it is an integration into the cosmos with the whole of existence. The integration into the cosmos, however, is not formal or objective, is not based on distinctions and relationships that represent a context in the world, not on norms, but it is about an inner feeling that results from meditation and ecstasy, albeit these techniques also depict the exercises that Zhuangzi makes fun of, as the ultimate goal is to go beyond them. Although Zhuangzi is, as it were, a jubilant witness to the success of these techniques, he also calls for them to be overcome. Zhuangzi is considered the end point of these techniques in later Daoism and is an illustration of the rejection and forgetting of them. This is one reason why the Daoist masters refer to Zhuangzi in relation to these practices and Zhuangzi justifies them by overcoming himself.

Zhuangzi knows two bases of life, Qi and Jing (for example: energy and essence). Qi is understood as neither material nor spiritual and as the sole substance. In later Daoism, qi and jing had the same meaning as in Zhuangzi. Qi is regarded as Yuanqi, the Qi of origin, to which most of the Daoist immortality techniques refer. Jing, on the other hand, is a term that has different meanings in later Daoism. Zhuangzi speaks of Jing as the basis of the physical and of the fact that the Zhenren values it, must not disturb it and must keep it complete and undamaged.

Zhuangzi sees it as important to realize the calm, quiet and freedom of thought already emphasized by Laozi. Later Daoists valued the silence techniques presented by Zhuangzi. For example Zuowang (sitting in oblivion, meditation) is practiced. Zhuangzi writes about Zuowang that body and limbs are given up, sharpness of perception is discarded, one's own form is abandoned, knowledge is given up and an identification with the all-encompassing greatness is made. (Chap. 6) Other teachings to which later Daoists attached great importance are the 'fasting of the heart-mind' and the 'mirror of the heart', which reflects the whole world, pure and undistorted, in its perfect totality. The term 'fasting of the heart' is associated with the term 'keeping the one', which comes from the Daodejing. 'Preserving the One' describes various meditation techniques and is a key term in Daoism. Zhuangzi says that the body must be erect and the mind must form a unity, after which one can attain heavenly harmony. One should collect the knowledge and the action should be directed towards the one, so that the spirits come to the dwelling. The upright body means a healthy body in the correct meditation position and the spirits refer to appearances of deities in the meditation chamber. The Daoist meditation is a collection and serves to close oneself off from the outside world. It serves as a retreat and a break with the world of the senses. Meditation is seen as a complement and preparation for an expansion that is without separation of inside and outside. This leads to the saint who moves in this expansion. The world of the individual is understood to be limited by sensual perceptions and thoughts. Closing oneself to the world of the senses is understood as opening to the cosmos, which is the unity that is achieved through cosmic Qi.

The human being

Zhenren

Zhuangzi's ideal of the sacred is the Zhenren ( 真人 , Zhēnrén - "true man"), with which he takes up a term that coined the Daodejing. The Zhenren is characterized by complete freedom of thought.

In order to show how this can be achieved, Zhuangzi first describes how people's spiritual bondage comes about:

“Master Ki said:“ Great nature expels its breath, it is called wind. Right now he's not blowing; but when he blows, all holes sound violently. Have you never heard that roar before? The mountain forests are steep slopes, ancient trees have hollows and holes: they are like noses, like mouths, like ears, like roof stalls, like rings, like mortars, like puddles, like pools of water. There it hisses, there it buzzes, there it screams, there it snorts, there it cries, there it complains, there it roars, there it cracks. The initial sound is shrill, followed by panting tones. When the wind blows gently there are soft harmonies; when a hurricane arises there are strong harmonies. When the terrible storm subsides, all openings are empty. Have you never seen how everything then quietly trembles and weaves? "The disciple said:" So the organ playing on earth simply comes out of the various openings, just as the organ playing man comes from tubes lined up in the same row. ""

“In sleep, the soul has intercourse. In waking life, physical life opens up again and deals with what it encounters, and the conflicting feelings rise daily in the heart. People are entangled, insidious, hidden. [...] Lust and anger, sadness and joy, worries and sighs, inconstancy and hesitation, lust for pleasure and immoderation, surrender to the world and arrogance arise like the sounds in hollow tubes, like damp warmth creates mushrooms. Day and night they take turns and appear without (the people) realizing where they sprout from. "

For Zhuangzi, feelings, affects and views arise purely mechanically, as when the wind blows into hollow openings and creates sounds. Like the different sized openings, people also have their own characteristics. If the external things penetrate them, the heart produces the feelings as the gust of wind produces the sound. Man only suffers what happens to him, but cannot behave creatively towards it. Zhuangzi contrasts this unfortunate condition of ordinary people with holy people. By shedding his self , i.e. his peculiarities, which offer the things of the outside world a surface to attack, he comes to silence and emptiness:

Master Ki von Südweiler sat with his head in his hands, bent over his table. He looked up at the sky and breathed, absently, as if he had lost the world around him.

One of his pupils, who stood in front of him in service, said: “What is going on here? Can one really freeze the body like dry wood and extinguish all thoughts like dead ashes? You are so different, master, than I usually saw you bent over your table. "

Master Ki said, “It is very good that you are asking about it. Today I buried myself. Do you know what this means? Perhaps you have heard people play the organ, but not heard the earth play the organ. Perhaps you have heard the organ on earth, but you have not yet heard the organ of heaven. "

Free of all things, the Zhenren also surpasses the ideal of Confucian philosophy, the noble one who masters the virtues of goodness, justice and manners, as the fictional conversation between Confucius (here: Kung Dsï) and his favorite student Yen Hui shows:

Yen Hui said: "I have made progress." Kung Dsï said: "What do you mean by that?" He said: "I have forgotten goodness and justice." Kung Dsï said: "That is possible, but it is not yet the ultimate." Another day he stepped in front of him again and said: "I have made progress."

Kung Dsï said: "What do you mean by that?" He said: "I have forgotten manners and music."

Kung Dsï said: "That goes on, but it is not yet the ultimate. "Another day he stepped up to him again and said:" I have made progress. "Kung Dsï said:" What do you mean by that? "He said:" I have calmed down and have forgotten everything . "

Kung Dsï said, moved:" What do you mean that you have come to rest and forget everything? "Yen Hui said:" I left my body behind, I have dismissed my knowledge. Far from the body and free from knowledge, I have become one with him who pervades everything. That is what I mean by the fact that I have come to rest and have forgotten everything. "Kung Dsï said:" When you have reached this unity, you are free from all desire; if you have changed in this way, you are free from all laws and are far better than me, and I only ask that I may follow you. "

The book “Zhuangzi” differs from Daodejing and Confucianism in its stronger rejection of the political. Instead, Zhuangzi aims at a change in human nature, a changed relationship to the self and the world that brings him into harmony with the Dao and all things. Dao, that is the eternal change of things with which the holy man keeps pace. He practices frugality and does not try to impose his will on things. Out of this mindset arises a skill and mastery, which can be seen, for example, in the craftsmanship (see below). It goes hand in hand with an inner serenity and self-forgetfulness.

The change in human nature that Zhuangzi is striving for is shown by a movement between being oriented towards the world and turning away from the world: On the one hand, there are passages that describe and praise the secluded self-cultivation, on the other hand, Zhenren is quite cheerful in the midst of world events. So it is not only about seeking salvation from the world and remaining in this state, but after times of retreat to step back into the lifeworld and matters of human activity and there through unity with the Dao a natural and to realize free interaction with people and things. This state is achieved through shedding the self and fasting the mind.

Fasting the mind

Man can reach the state of Zhenren by fasting "the spirit" or also the "innermost self". The fasting abstains:

- His talents and his skill, because it is dangerous for him: The cinnamon tree is felled, the beautiful fur of foxes and leopards is their corruption.

- He abstains from sensual pleasures because they cloud the mind and disturb the heart.

- Likewise, the sage does not indulge in any strong outbursts of emotion: he even faces the death of the great master Laozi with serenity.

- Even too much knowledge leads the world into chaos: the rational mind invents the bow that chases the birds away, it practices rhetoric , which in great speeches then throws natural understanding into confusion.

- The wise man also fasts moral and immoral behavior into insignificance, because both lead human relationships into inextricable entanglement.

While the inner chapters give a representation of how the constantly changing feelings arise in humans - like tones in cavities - the outer chapters provide explanations that expand the first with metaphysical considerations on the relationship between being and nothing . The reason for the conflicting passions and views then turns out to be that ordinary people hold only to the material world , to what is or what is not . For the “Zhuangzi”, on the other hand, all being and non-being emerges from a not-yet-being .

This not-yet-being, which is the origin of all things, distinguishes the “Zhuangzi” from both being and not-being. This is because not-being is represented merely in terms of being, namely by negating being. The not-yet, on the other hand, eludes any representation, since it cannot be presented as something negated. It is the not-yet-being that first nourishes the opposites. A view that is possibly based on the Daodejing. There it says:

"Thirty spokes meet in a hub:

on the nothing about it (the empty space)

the car's usefulness is based."

The opposites of being and not-being, which are important for our conduct of life and which are expressed as life and death, good and bad, success and failure, arise only from being-not-yet. However, the more you cling to one of these extremes, the more the other comes to the fore. Not only with regard to the striving of the human being, but also with regard to his understanding of the world, the standpoint of being or non-being is to be avoided, because only on this level do the contradictions arise. If one takes man, for example, for a rational being in order to justify his freedom through reason, then one makes him unfree at the same time, because if his thinking merely follows rational laws, then he loses his status as an individual. If, on the other hand, you want to see him as an individual, then his behavior must not be predictable, so he must act irrationally, which, however, runs contrary to his freedom guaranteed by reason. The "Zhuangzi" now assumes that both possible considerations are equally wrong. This is because both are only explanations . However, it is a mistake to keep the explanation for being, because, first designed the human being the statements by his observations of the world from these only, on the other hand, the observer is itself subject to eternal change, his views change accordingly with the times . If one takes the abstract explanations for being in spite of everything, then this is always at the expense of an original and spontaneous way of life: Either we only see a dead world that runs mechanically, or we are completely without reference to it, since we only deal with it orient ourselves to the laws we have gained. According to Zhuangzi, both of these negate the essence of man.

Only by withdrawing from the standpoint of being and the opposites that result in it, which always throw one back and forth, one arrives at the original, preceding standpoint of not-yet-being.

However, fasting the mind by no means leads to passive inactivity. Because only with an empty self that has not yet clung to being or not-being can one correspond to what the circumstances demand: every incident has its appropriate way of acting, which cannot be referred back to one's own wishes, or its measure could be derived from general rules derived from being. This realization points to the innermost contradiction of life itself: in order to be able to take the world as it is, one must first be free from it, i.e. H. free from feeling, knowing and doing. Fasting thus becomes a first condition to step fully into the world and to freely follow and correspond to the eternal change of things.

So transformed, it is no longer individual things to which the heart clings. The mind is not an intentional one that focuses on something. The true self of man is not the sum of our desires and the intentionally grasped objects; it is not shaped by the outside world, but rather lies beneath these needs that come from the outside. In “Zhuangzi” happiness is therefore the state in which we return to our true selves. Reaching him is one of the tasks of life and fasting of the spirit serves as a means for this. If you reach it, you know this for yourself: It is a state in which neither grief oppresses you, nor joy makes you exuberant, but grief and joy are just as they are, just there . Whoever overcomes the hungry-intentional self in this way has regained his heaven- given nature. He will not seek to subordinate the course of things to his ideas through technical interventions or to accelerate it, but is a "companion of heaven".

If you have fasted empty and overcome the realm of either / or, passions and desires, then you fit into the world, whereby the Chinese term ( shih ) also has the meanings of ease of movement, comfort, happiness:

“If you have the right shoes, you forget your feet; if you have the right belt, you forget your hips. If you forget all the pros and cons in your knowledge, then you have the right heart; if one no longer wavers inside oneself and does not follow others, then one has the ability to deal with things properly. Once you have reached the point where you hit the right thing and never miss the right thing, then you have the right forgetting of what is right. "

Unspeakable

"The one

who knows does not speak, the one who speaks does not know."

The Dao , the path itself, cannot be said, because one can only say about the things that are . But since the Dao is not a thing, it cannot be spoken of suddenly, it can only be said that it cannot be spoken of. Speechlessness remains the highest goal in the “Zhuangzi” .

“Heaven and earth arise with me at the same time, and all things are one with me. Since they are now one , there cannot be another word for it; as they on the other hand than one referred to, so must there also be a word for it. The one and the word are two; two and one are three. From there one can go on saying that even the most skilful computer cannot follow how much less the mass of people! If you already reach being from non-being up to three, where do you get to if you want to reach being from being! You don't achieve anything with it. So enough of it! "

So if you want to talk about the (still) -not-being of things, if you want to "reach being from non-being", you will fail, because with every word about it something that is just comes into the world that is between distinguishes between right and wrong , separates above and below , relates hot and cold . So if language fails to express itself about simple non-being, how much more must it go wrong if it is to name things within being, if someone “wants to reach being from being”. Zhuangzi therefore also rejects relativism , since it remains in the plane of being and things. To grasp the relationships of reality in language, however, only leads to an infinite stringing together and concatenation of terms without end and starting point. Zhuangzi, on the other hand, aims with his teaching at a state where things have not yet entered being.

Zhuangzi gives some formulations that summarize the relativistic teaching of the time:

“In the whole world there is nothing bigger than the tip of a downy hair” and: “The big mountain is small”. "There is nothing older than a stillborn child" and: "The old grandfather Pong (who lived his six hundred years) died at an early age". "

Although some modern philosophers saw relativism in this, it is not Zhuangzi’s goal to use such sayings to justify a relativistic doctrine that already existed at the time (for example in the sophisms of Yan Hui ). And so Zhuangzi also wonders to what extent his theory can be equated with these relativistic views: “Now there is still a theory [sc. the relativistic sayings quoted above]. I do not know whether you will deal with the [sc. those Zhuangzis] are of the same kind or not. "

Zhuangzi's twisted linguistic utterances can only be interpreted as relativistic when they are taken literally. Rather, the goal of such passages is precisely to overcome relativism through the impossibility and nonsense of these statements and the headache about them. Relativism can only be overcome by clinging to the change of things, to the Dao, which takes place in different stages:

“It is easy to reveal the SENSE of what is called to a man who has the appropriate talent. If I had him with me for instruction, after three days he should be ready to have overcome the world. After he had overcome the world, I wanted to take him so far in seven days that he would stand outside the opposition of subject and object. After another nine days, I wanted to bring him to the point where he would have overcome life. After overcoming life he could be as clear as the morning, and in this morning clarity he could see the one. If he saw the One, there would no longer be a past and a present for him; beyond time he could enter the realm where there is no more death or birth. "

The unity with the Dao leads to an area that no longer emphasizes the relativity of differences, an area "where there is no more death or birth". It becomes clear here that “immortality” is achieved through a changed mental attitude of the human being, that is, because of forgetting himself and forgetting about birth and death. Later interpretations, which read the corresponding passages literally, understood this as magic longevity and immortality techniques, as they were then also characteristic of later Daoism. (See Daoism as a Religion .)

death

For Zhuangzi, life and death were like two worlds, between which there is no window through which one could look from one to the other. Therefore, it cannot be said which of the two is preferable, a headache over this will not do anything. A humorous story plays out the otherness of the two worlds:

Dschuang Dsï once saw an empty skull on the way, which was bleached but still had its shape.

He tapped him with his riding crop and began to ask him: 'In your greed for life, have you deviated from the path of reason that you got into this position? Or did you ruin an empire and were put to death with a hatchet or an ax that you got into this situation? Or have you led an evil conduct and brought shame on father and mother, wife and child, that you got into this situation? Or did you perish from the cold and hunger that you got into this situation? Or did you come into this position after life's spring and autumn came to an end? "

When he had said these words, he took the skull to the pillow and slept. At midnight the skull appeared to him in a dream and said: “You were talking like a gossip. All you mention is just worries of living people. There is nothing like that in death. Would you like to hear something about death? "

Dschuang Dsï said: "Yes."

The skull said: In death there are neither princes nor servants and there are no changing seasons. We drift, and our spring and autumn are the movements of heaven and earth. Even the happiness of a king on the throne is not equal to ours. "

Dschuang Dsï did not believe him and said: “If I can enable the Lord of Fate to bring your body back to life, to give you flesh and bones and skin and muscles again, to give you father and mother, wife and child and returns all neighbors and friends, would you agree? "

The skull stared with wide eye sockets, frowned and said:

"How can I throw away my royal fortune and take on the troubles of the human world again?"

- Qi

| In addition to the human-related meaning, there is also a world-related meaning of Qi , which appears in the "Zhuangzi" : Earth and heaven Qi appear as two complementary natural forces, occasionally the one Qi is also the basis of the world Speech that shows responsible for the course of the world. |

The "Zhuangzi" knows no transmigration of souls or a "passing over of the ego". Rather, life is only understood as a temporary coming together of the body, which ends when the body comes apart. This becomes clear in passages in which Zhuangzi speculates about what might become of him after death: “If he [sc. an imaginary creator] now dissolves me and transforms my left arm into a rooster, so I will call the hours at night; if he dissolves me and turns my right arm into a crossbow, I will shoot down owls to roast; if it dissolves me and transforms my hips into a carriage and my mind into a horse, I will mount it and need no other companion. ”The coming together of the life force is brought about by the Qi ( 氣 / 气 ), a term that Common property of all Chinese philosophical schools. If it occurs in the “Zhuangzi” in relation to humans, it has the meaning of life force or breath here . Its coming together causes life, its falling apart causes death. Both processes are as unspectacular as the course of the seasons and like this are accepted with serenity. A story tells the Zhuangzi about the death of his wife:

“[A] When I reflected on where she came from, I realized that her origin lies beyond birth; yes, not only beyond birth, but beyond corporeality; yes not only beyond the physicality, but beyond the qi. There was a mixture of the incomprehensible and the invisible, and it changed and had qi; the qi transformed and had corporeality; the corporeality was transformed and was born. Now there was another change and death occurred. These processes follow one another like spring, summer, autumn and winter, as the cycle of the four seasons. And now she is lying there and slumbering in the great room, how should I weep for her with sighs and complaints? That would mean not understanding fate. That's why I'm giving up on it. "

Accordingly, Zhuangzi also saw his own funeral calmly, which indifference must have been a thorn in the side of the Confucians with their strict funeral rites. For Zhuangzi, on the other hand, it was man's natural attitude, which was only later overtaxed by culture and rites: “The true people of the past did not know the pleasure of being born or the disgust for death. … They went calmly, they came calmly. ”One of the last chapters tells of the death of Zhuangzi:

Dschuang Dsï was dying, and his disciples wanted to bury him magnificently.

Dschuang Dsï said: "Heaven and earth are my coffin, the sun and moon shine for me as lamps for the dead, the stars are my pearls and precious stones, and all of creation is my mourning companion." I have a splendid funeral! What else do you want to add? "

The disciples said: "We are afraid that the crows and harriers would like to devour the master."

Dschuang Dsï said: Unburied I serve crows and harriers for food, buried worms and ants. Take it from one person to give it to the other: why be so partial? "

The world

Heaven and man

Zhuangzi explains his attitude towards culture based on the relationship between heaven ( 天 , tiān ) and people, which comes from mythology . However, heaven is no longer a moral deity here, who decides on the mandate of the ruler ( 天命 , tiānmìng ), but from him people and things have their form or shape ( 形 , xíng ). The most important quote on this comes from one of the most famous books of the "Zhuangzi" , the "Autumn Floods" :

“That oxen and horses have four legs, that is, their heavenly (nature). To curb the horses' heads and to pierce the noses of the oxen, that is, human (influence). "

In the broadest sense, one could say that heaven is something like “the nature of things”, what defines their being-by-itself, which is why Wilhelm usually translates tian as “nature”. Both are in a sense opposed to each other: For humans, however, there is the possibility of following the “path of heaven” or the “path of man”. Since the "Zhuangzi" assumes that the world happens in its course without humans, interventions in nature and the natural attitude of humans are seen as superfluous: "Webbed toes and a sixth finger on the hand are formations that go beyond nature and are superfluous for actual life. "

Zhuangzi now asks how it is possible for humans to lead a life in such a way that it does not bring the relationship between heaven and humans into imbalance. First of all, it must be possible to distinguish between the two, which Zhuangzi explains in Book VI: "To know the workings of nature and to recognize the relationship between human workings: that is the goal." Relating to the outside, a problem arises: “But there is a difficulty here. Knowledge depends on something outside of it in order to prove to be correct. Since what it depends on is uncertain, how can I know whether what I call nature is not man, whether what I call human is not actually nature? ”Zhuangzi points out on the inner being of man, his “heavenly nature”, which allows him to recognize the right way: “The true man is needed so that there can be true knowledge.” These true people (Zhenren) are characterized as follows: “The true Ancient people did not shy away from being left alone (with their knowledge). They did not perform any exploits, they did not make plans. [...] The true ancients had no dreams while sleeping and no fear when waking. Their food was simple, their breath deep. Real people draw their breath from the bottom, while ordinary people only breathe with their throats. [...] The true people of the past did not know the pleasure of being born or the abhorrence of death. [...] In this way they achieved that their hearts became firm, their faces immobile and their foreheads simply serene. "

If the way of heaven is recognized through this attitude to life, the true man can follow it without hurting him. He acts without intervening, his acting is “without doing”: Wu wei.

Wu Wei

In the "Zhuangzi" the venerable intentions of the wise men are recognized, who, like Confucius, set up rules to order human society. On the other hand, there are also sections in “Zhuangzi” that are in sharp contrast to the Confucian School. While for Confucius only the social commitment of man could guarantee the order of the world, the "Zhuangzi" sees precisely in the rules established by the wise the cause of the unrest and the imbalance. Therefore it is said:

“I know from this that one should let the world live and let it go. I don't know anything about putting the world in order. To let them live, that is, to be concerned that the world does not twist its nature; to let them have their way, that is, to be concerned that the world does not deviate from its true LIFE [sc. De ]. If the world does not twist its nature and does not deviate from its true LIFE, the order of the world has already been achieved. "

So the world is not a task . It has already been reached. The philosophy of the "Zhuangzi" is shaped by a trust in the course of the world, which happens entirely by itself. The world does not have to be set up so that people can live in it. The "Zhuangzi" refers to a natural original state:

“In the golden age, people sat around and didn't know what to do; they went and did not know where to go; They were mouthful and happy, pounded their bodies and went for a walk. That was the whole ability of the people, until then the "saints" (sc. The wise men) came and worked out manners and music to regulate the behavior of the world, hung up moral codes for them and made them jump afterwards ... "

The world did not need order, it was completely at rest by itself. In order to restore this state of affairs, the “Zhuangzi” recommends the Wu knows, not acting: “Therefore, when a great man is forced to deal with the government of the world, the best thing is not to act. By not acting one comes to calmly coming to terms with the conditions of the natural order. ”In this context, inactivity does not mean that one should do nothing at all. Rather, it refers to not intervening in the rule of the Dao, which by itself keeps the world in order. The attitude of Wu Wei is illustrated in the "Zhuangzi" on the basis of three main points:

- Don't overestimate the benefits

“Dsï Gung had hiked in Chu State and returned to Dzin State. As he passed the area north of the Han River, he saw an old man who was busy in his vegetable garden. He had dug ditches for irrigation. He went down into the well himself and brought up a vessel full of water in his arms, which he poured out. He worked to the utmost, but achieved little.

Dsï Gung said, “There is a facility that can water a hundred ditches in a day. Much is achieved with little effort. Don't you want to use them? "

The gardener straightened up, looked at him and said: “And what would that be?” Dsï Gung said: “You take a wooden lever arm that is weighted at the back and light at the front. In this way you can draw the water so that it just bubbles. It's called a draw well. "

Then the anger rose in the old man's face and he said with a laugh: "I heard my teacher say: If someone uses machines, he does all his business by machine; Anyone who does their business by machine gets a machine heart. But if someone has a machine heart in his chest, he loses pure simplicity. With whom the pure simplicity falls, he becomes uncertain in the impulses of his spirit. Uncertainty in the movements of the mind is something that is inconsistent with the true SENSE. Not that I didn't know things like that: I'm ashamed to use them. ""

- Not helping the way of heaven

The attitude of Wu wei also relates to supposedly positive intervention in the being-by-itself of things and living beings:

“The Marsh Pheasant has to walk ten paces before he finds a mouthful of food and a hundred paces before he has a drink; but he does not desire to be kept in a cage. Although he would have everything his heart desires there, he doesn't like it. "

- Political intervention

“Giën Wu visited Dsië Yü, the fool.

Dsië Yü, the fool, said: "What did the beginning of noon speak to you?" Giën Wu said: "He told me that when a prince himself shows the guidelines and rules people by the standard of justice, nobody it will dare to refuse obedience and reform. "

Dsië Yü, the fool, said: “That is the spirit of deception. Whoever wanted to order the world in this way would be like a person who wanted to wade through the sea or dig a bed in the Yellow River and charge a mountain to a mosquito. The order of what is called: is that an order of external things? It is right, and then it is possible that everyone really understands their work. The bird flies high in the air to avoid the archer's arrow. The shrew digs deep into the earth to avoid the danger of being smoked or dug up. Should people have fewer means than the unreasonable creature (to evade external coercion)? ""

Ultimately, the zeal to regulate the world politically is in vain, because on the one hand this is as superfluous as if you wanted to dig a bed for the Yellow River, on the other hand people already know how to escape the regulations and laws how the bird flies up to escape the arrow.

Conformability

The attitude of Wu Wei does not only show itself through a mild and nevertheless shielding rule or in the omission of comprehensive interventions in nature (the way of heaven), but also in the everyday practical things of life. This illustrates the story of the cook Pong, in which the conformability to things and the world is made clear:

"[The cook] put on a hand, squeezed with his shoulder, put his foot down, braced his knees: ritsch! ratchet! - the skin parted and the knife hissed through the pieces of meat. Everything went like a dance song, and it always hit exactly [between] the joints. "

The cook said to the prince:

“When I started cutting cattle, all I saw was cattle. After three years I had gotten to the point that I could no longer see the cattle undivided in front of me. Nowadays I rely entirely on the mind and no longer on the appearance. ... I follow the natural lines, penetrate the large crevices and drive along the large cavities. I rely on the (anatomical) laws. I skilfully follow even the smallest spaces between muscles and tendons ... A good cook changes the knife once a year because he cuts . A bumbling cook has to change the knife every month because he chops . "

Cutting instead of chopping - that would be the snugness of a Zhenren. Instead of using force to enforce his will against things, to hack, the Zhenren hugs things. By following the Dao, he lets his knife slide through the cattle so that it is cut up and disintegrates into its individual parts by itself. There are other similar stories in the “Zhuangzi” , which deal with the fact that the craftsmanship, which corresponds to the Dao, is not to be conveyed literally, but only occurs in action. Today's interpretations of Western authors see in this story the theoretical unfolding of a contrast between technical and intuitive knowledge.

At the same time, the story is a parable of the way of life: After the cook gave his lecture, the prince thanks him with the words: “Excellent! I've heard the words of a cook and learned to care for life. ”The words of a cook (and not a priest!) Reveal the best way to live: to be thin as a blade and to slide between people and their quarrels not to excel with one's abilities. Zhuangzi raises the ideal of being useless in relation to human demands: one escapes like a tree "whose branches are crooked and gnarled so that no beams can be made out of it" and "whose roots burst apart so that coffins cannot be made out of it" the use in an office or profession, leads a long life undisturbed and thus ends its number of years. (Book IV: 4, 5, 6). Zhuangzi also connects this with the concept of trace : If people and wise men follow the Dao, then "their deeds leave no trace and their works are not told."

politics

The most important political question of the time was how to keep human relationships in order, that is, the question of morals . While the Confucians fought for strict adherence to morality and the submission of the individual to the group, Zhuangzi emphasizes that moral rules are only man-made. They are only necessary because people deviate from their original and peaceful nature. However, they do not lead to a new orderly state, but instead plunge interpersonal relationships into even more entanglements - people fall away from the Dao, they forget the path of heaven.

Even if it were to succeed in politically enforcing compliance with all rules, this is not the end of the story, because precisely now there is a risk of abuse:

“Against thieves who break into boxes, search pockets, tear open boxes, secure by looping ropes and ropes around them, fastening bolts and locks, that's what the world calls cleverness. But if a big thief comes, he takes the box on his back, the box under his arm, the bag over his shoulder and runs away, just worried that the ropes and locks are securely held. "

So while you protect yourself against the little thieves with the moral, like you put a lock on the box, the big thieves steal the whole box and are happy that it is locked so tight when you carry it away. Likewise, the morals and virtues of ordinary people serve the tyrant to subdue the land. He steals the whole box straight away and will not even have to fear punishment for it: “If someone steals a clasp, he will be executed. If someone steals an empire, he becomes a prince! "

The "Zhuangzi" sees the sermons of the holy sages and scholars as the reason for the predatory princes and the never-ending moral entanglements (although it is not clear whether Confucius himself can be counted here):

“Every cause has its effect: If the lips are gone, the teeth are cold. Because Lu's wine was too thin, Han Dan was besieged. Likewise, when saints are born, great robbers arise. That is why one must drive out the saints and leave the robbers to their own devices; only then will the world be in order. "

Philosophizing

reason

The following story from the Zhuangzi is particularly well known, its title is The Joy of Fish . Zhuangzi talks to Hui Shi (approx. 300–250 BC, here: 'Hui Dsi') a main representative of the sophist school ( mingjia ):

“Dschuang Dsi once went for a walk with Hui Dsi on the bank of a river. Dschuang Dsi said: “How funny the trout jump out of the water! That is the joy of fish. "Hui Dsi said:" You are not a fish, how do you want to know the joy of fish? "Dschuang Dsi said:" You are not me, how can you know that I am the joy of Don't know fish? "Hui Dsi said:" I am not you, but I cannot recognize you that way. But you are certainly not a fish, and so it is clear that you do not know the joy of fish. "Dschuang Dsi said:" Please let us return to the starting point! You said: how can you see the joy of fish? You knew very well that I knew her, and you asked me anyway. I recognize the joy of fish from my joy in hiking on the river. ""

By referring to the starting point of the conversation, Zhuangzi also comes back to what was immediately given: "You knew very well that I knew her." The world is always as it is evident: the joy of fish does not need any explanation, no return to a ground that assures the truth. All subsequent attempts to discursive and argumentative to create be- must fail because there is nothing to knowledge could draw near about the joy of fish and could make them as still "apparent". On the other hand, it is nonsensical to reject the obvious and then ask about something else that might justify it. The methodical doubt is Zhuangzi foreign.

argumentation

Since Zhuangzi refused to let the mind look for reasons and to orientate itself to them, he also rejected the associated claim to justification, i.e. the obligation to justify his opinion in conversation. The rationally conducted discourse, the rules of which are determined by the argument, is not a means of finding the truth:

“Suppose I argued with you; you defeat me and i don't defeat you. Are you really right now? Am I really wrong now? Or I will defeat you and you will not defeat me. Am I really right now and you really wrong? Is one of us right and one wrong, or are we both right or both wrong? Me and you, we can't know. But when people are in such confusion who should they call to decide? Shall we get one who agrees with you to decide? Since he agrees with you, how can he decide? Or should we get one who agrees with me? Since he agrees with me, how can he decide? Should we get someone who deviates from both of us to decide? Since he differs from both of us, how can he decide? "

Zhuangzi was aware of the social function of the discourse, which he rejected as secondary: "The one who is called has (the truth) as an inner conviction, the people of the crowd try to prove it in order to show it to one another." The will, one another to convince or to outdo the other argumentatively is already rooted in the individual egoisms. The Dao itself does not need proof, for just as great love is not loving (because it includes everything) and great courage is not foolhardy (because it is not foolhardy too ), everything is included in the Dao. It is not a property of something itself, but it cannot be grasped linguistically and therefore it is said "If you try to prove with words, you will not achieve anything."

Effect and reception

In China

- General

The work is not one of the most highly regarded in Chinese intellectual history and was almost completely forgotten during the Han period . On the other hand, literary beauty has been undisputed over time, and many of the stories from the book Zhuangzi have become topoi in Chinese literature that have been taken up again and again over the centuries.

The "Zhuangzi" had a great influence on the original Chinese direction of Buddhism, the Chan Buddhism. With the penetration of Buddhism in China a new interest in metaphysical speculations arose, which encouraged the preoccupation with the "Zhuangzi" . Many terms of the "Zhuangzi" have also been used to translate Buddhist Sanskrit Sutras. Similarities can be seen in terms such as “self-forgetting”, “mindlessness” (in the positive sense, wu xin , literally: without heart / mind) and “meditation” ( zuo wang , literally: sitting in self-forgetfulness) as well as the rejection of world-bound emotions.

- Commentary tradition

The comment is in China and Europe is the attempt, an ancient text that you think is valuable to help with a new explanation of understanding. Most of the time, the claim is made to merely adopt the tradition of the old teaching, even if, of course, there is also the possibility of giving the text your own interpretations. It is estimated that between 200 and 500 comments were made on the “Zhuangzi” .

One of the most influential commentators is the editor of the text version available today, Guo Xiang (253-312). His interpretation is formative for everyone who follows. Guo introduces his comment by saying that Zhuangzi did not write a classic ( bu jing ), but is at the head of the "hundred schools". In doing so, he assigns it a high rank, but at the same time places the “Zhuangzi” under the Daodejing or Confucian works. A classification that was mostly taken up in the following commentary tradition. Guo is mainly dedicated to Zhuangzi's philosophy of spontaneity. Compared to his predecessor Wang Bi , for him the Dao is not a transcendent world principle to which all things and beings strive and which guarantees their spontaneity. Guo turns the superordinate Dao into an immanent individual principle of things: It changes with things and finds fulfillment when the individual things correspond to their nature. Because of this immanence of the Dao, Guo can no longer be held responsible for the creation of the world in the function of a creative force. Also, Guo does not know of any substances that have been preserved during eternal change. Despite the great importance of his commentary, Guo was not just concerned with the representation and preservation of the original Zhuangzi, and so many of his interpretations are quite idiosyncratic.

Other important commentators are: Cheng Xuanying (approx. 620–670), a Daoist monk and main representative of the “school of the double mystery” ( chongxuan xue ), who is interested in Zhuangzi's theory of emptiness and places Guo's interpretation in a religious-Buddhist context . In the Song Dynasty, the scribe Wang Pang (1042–76). Lin Xiyi (approx. 1200–73) in the Ming dynasty gives less philological information than a free interpretation of the content, which takes up the most diverse currents of Chinese philosophy and Buddhist sutras for interpretation. Subsequently, Luo Miandao (approx. 1240–1300) and Jiao Hong (1541–1620) are important.

However, some of the interpreters of the “Zhuangzi” are said to have failed because of this extraordinary work, and so misunderstandings and misinterpretations are assumed. The main misunderstandings are:

- Zhuangzi is only seen as a commentator on Laozi. This ignores the peculiarities and new philosophical ideas of the work. Western interpreters and translators such as Giles , Legge and Watson often made the same mistake .

- The "Zhuangzi" has often been identified with Zen Buddhist ideas. On the other hand, the two traditions of thought differ markedly: while in Buddhism everything is false and untrue, everything is right and true for Zhuangzi, while the metaphysics of Buddhism is idealistic, Zhuangzi represents a realism when the state of nirvana in Buddhism tends to be metaphysical, thus, Zhuangzi's fasting of the mind and sitting in oblivion is a state related to the cognition of the world. In the course of mixing these elements, the Zen Buddhist Suzuki , for example, interpreted the butterfly dream to the effect that there is no difference between dream and reality in the sense of a Buddhist unity , whereas Zhuangzi's philosophy emphasizes the difference (but equivalence ) of the perspectives.

- Another misunderstanding sees Zhuangzi as a decadent thinker of an age of decline who mourns the pitiful state of the world. The book is aimed at rebels, socially excluded and worldly failures and recommends them to withdraw from the world into a mystical, naturalistic and romantic original state.

- Because of his paradoxical attacks on morals, Zhuangzi was often mistaken for a hedonist. Then there is a reading that simply understands the Wu Wei as doing nothing at all, which is only possible if individual parts are picked out of the overall work. However, it cannot be said that his ideal was a hedonistic egoism , as can already be seen in the many text passages where surrendering to external things is problematized.

- The misunderstandings listed led to the fact that Zhuangzi was given various titles. He has been called a skeptic , nihilist , fatalist , relativist or even an evolutionist . At the same time, these different awards from the tradition of Western philosophy lack the peculiarity of the Zhuangzi. For example, Zhuangzi cannot be called a skepticist because he was not thinking cognitivistically at all . He cannot be considered a nihilist, since he did not reject values and norms entirely, but rather sought them in harmony with the natural "order". If evolution assumes a direction of development, then he cannot be regarded as a representative here either, since for him there was only the universal change of things, which however does not proceed in a straight line. He cannot be called fatalistic, because his philosophy tries to lead people towards a spontaneous relationship with themselves and the world. He will also not have represented a relativism, namely if the Dao embraces and governs all things in the universe, then there is no room for an artificial situationism.

- The book as a whole is often taken as a typical example of the age of decay. The work was shaped in his views by the tremors of the age and had no value beyond a historical document as a philosophical writing. According to this view, its use consisted only in having served as a comforter for contemporaries.