Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (born September 26, 1889 in Meßkirch ; † May 26, 1976 in Freiburg im Breisgau ) was a German philosopher . He stood in the tradition of phenomenology, primarily Edmund Husserl , the philosophy of life in particular Wilhelm Diltheys and Søren Kierkegaard 's interpretation of existence , which he wanted to overcome in a new ontology . The most important goals of Heidegger were the criticism of occidental philosophy and the intellectual foundation for a new understanding of the world.

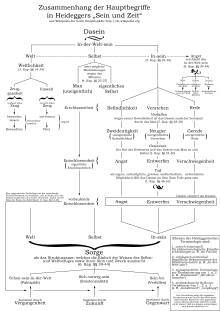

In 1926 he wrote his first major work, Being and Time , which established the philosophical direction of fundamental ontology (published in 1927).

From mid-1930 onwards, Heidegger began to interpret the history of Western philosophy as a whole. To this end, he examined the works of important philosophers from a phenomenological, hermeneutic and ontological point of view and tried to expose their “thoughtless” assumptions and prejudices . According to Heidegger, all previous philosophical drafts represented a one-sided view of the world - a one-sidedness that he saw as a feature of every metaphysics .

From Heidegger's point of view, this metaphysical conception of the world culminated in modern technology . With this term, he did not associate, as is usual, a neutral means of achieving ends. Rather, he tried to show that technology was also accompanied by a changed view of the world. According to Heidegger, technology brings the earth into focus primarily from the point of view of making it usable. Because of its global distribution and the associated relentless “exploitation” of natural resources, Heidegger saw technology as an unavoidable danger.

He juxtaposed technology with art and from the end of the 1930s he worked on a. a. alternatives to a purely technical world reference based on Hölderlin's poems . In late texts from 1950 onwards, he increasingly devoted himself to questions of language . Their historically grown wealth of relationships should avoid metaphysical one-sidedness. Heidegger tried not to think of people as the center of the world, but rather in the overall context of a world that he called " Geviert ". Instead of ruling over the earth, man must in it as mortal host live and protect .

A broad reception made Heidegger one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century. Nevertheless, the content of his work is controversial. Primarily, his National Socialist commitment is the subject of controversial debates to this day. Heidegger was a member of the NSDAP from 1933 to 1945 and in 1934 one of the founding members of the Committee on Legal Philosophy of the National Socialist Academy for German Law , headed by Hans Frank . Through the publication of the Black Booklet 2014/2015 as part of his complete works, u. a. previously unknown anti-Semitic statements made public.

life and work

Childhood, adolescence and studies

Martin Heidegger was born on September 26, 1889 as the first child of the married couple Friedrich and Johanna Heidegger (née Kempf from Göggingen ) in Meßkirch ( Baden ). His sister Maria was born in 1892, his brother Friedrich (Fritz) in 1894 . His father was a master cooper and provided at the local Catholic Church the office of sacristan . The family lived in simple but well-ordered circumstances. The deeply religious parents tried to get their children as good an education as possible, despite their tight financial resources, and also had their sons called into the altar service at an early age . Higher education beyond the parish school seemed unattainable until the local pastor, Camillo Brandhuber, became aware of Martin's talent in 1903 and enabled him to receive a scholarship for the Konradihaus in Konstanz , an archiepiscopal study home for the training of future clergy, and to attend the grammar school .

From 1906 Heidegger lived at the episcopal seminary in Freiburg and graduated from high school. After graduating from high school , he entered the Jesuit order as a novice in Feldkirch ( Vorarlberg ) in September 1909 , but left the monastery after a month due to heart problems. Instead he became a seminary student and began studying theology and philosophy at the University of Freiburg . Heidegger published first articles and comments. On February 16, 1911, the family doctor of the Collegium Borromaeum, Heinrich Gassert , diagnosed the theology student Martin Heidegger with nervous heart problems of an asthmatic nature, which prompted Gassert to suggest to the Konviktdirektor that Heidegger should be discharged after his homeland to allow a few weeks "complete rest to have". Heidegger was then given leave of absence for the entire summer semester of 1911, and he was advised to forego studying theology entirely. Heidegger followed this advice, gave up studying theology entirely in 1911 and added mathematics , history and natural sciences to philosophy . Since neo-Kantianism and a rejection of pre-Kantian ontology which was shaped by it predominated at philosophical seminars , Heidegger's early educational path was rather atypical due to its connection to Catholicism .

Two texts shaped Heidegger during this time: Franz Brentano's book On the manifold meanings of beings according to Aristotle and On Being. Outline of the ontology of the Freiburg dogmatist Carl Braig , whose lectures he attended. This created a fruitful tension between the scholastic tradition. Heidegger later judged that without his theological origin he would not have been put on his way of thinking.

In autumn 2014 it was announced that the German Literature Archive Marbach had acquired 572 previously unpublished letters and 36 postcards from correspondence with his brother Fritz. In the summer of that year the literature archive received 70 letters from Heidegger and his wife to his parents from 1907 to 1927. Heidegger had already given a large part of his estate to the archive himself.

Family & relationships

In 1917 Heidegger married Elfride Petri (1893–1992). She was a Protestant ; Engelbert Krebs married the two of them in the university chapel of the Freiburg Minster on March 21, 1917 according to the Catholic rite, and four days later they married in Wiesbaden as a Protestant.

In January 1919 the first son Jörg († 2019) was born, in August 1920 Hermann († 2020): His biological father was the doctor Friedrich Caesar, a childhood friend of Elfride, about which Martin Heidegger was informed, but this was not until 2005 the publication of Martin Heidegger's letters to his wife came to light. The two apparently lived a so-called open marriage .

Heidegger had an affair with the educator Elisabeth Blochmann , with whom he exchanged letters about her dismissal due to her Jewish origin after the " seizure of power " by the National Socialists in 1933. She was a friend and former classmate of Elfride Heidegger.

From February 1925, Heidegger had a love affair with his eighteen-year-old, also Jewish student Hannah Arendt . Letters from him to her and her notes on this relationship were found in her estate, while letters from her to him have not survived. From his early correspondence with the student it emerges what conception he had of a university-educated woman: “Male questions learn awe from simple devotion; One-sided occupation learn worldwide from the original wholeness of womanly being. ”On April 24th of the same year he wrote:“ Tornness and despair can never produce anything like your serving love in my work. ”The relationship was unbalanced: Since Heidegger neither his position nor wanted to endanger his marriage, he determined the time and place of their meetings; the contacts had to take place in secret. The love affair only became known after both deaths. In the winter semester of 1925/26, Arendt went to Heidelberg on Heidegger's advice to study with Karl Jaspers . There were still individual meetings until Heidegger ended the relationship in 1928. The relationship was of lifelong importance for Heidegger, even if there were long periods of no contact, especially from 1933 to 1950. However, he did not refer to Hannah Arendt's publications in any of his works and is also included in private correspondence never said a word about the work she had sent him.

Brother Fritz

The best expert on Martin Heidegger's writings and trains of thought was his brother Fritz , who was five years his junior . He transcribed all the texts published during his brother's lifetime from his hard-to-read manuscripts into appropriate typescripts .

Early creative period

In 1913, Heidegger earned his doctorate in philosophy with Artur Schneider with the work The Doctrine of Judgment in Psychologism . He was very active in the Freiburg Cartel Association of Catholic German Student Associations until he was called up for military service and regularly took part in the weekly meetings. In 1915 he gave a lecture there on the concept of truth in modern philosophy.

As early as 1915, he completed his habilitation under Heinrich Finke and Heinrich Rickert as a second reviewer with the work The Categories and Meaning Theory of Duns Scotus and the lecture The Concept of Time in History . In his habilitation thesis, Heidegger referred on the one hand to Duns Scotus' theory of categories and on the other hand to the script Grammatica Speculativa - later attributed to Thomas von Erfurt and not to Scotus - a treatise on types of linguistic expressions and ontological categories corresponding to them. Here Heidegger's early interest in the relationship between being and language is evident. Here Heidegger tries to make medieval philosophy fruitful for the present with the conceptual and methodological means of modern thought, above all phenomenology.

The First World War interrupted his academic career. Heidegger was called up in 1915 and assigned to the post and weather observation services. He was not suitable for combat missions; the withdrawal took place in 1918.

In 1916, Edmund Husserl became the leading phenomenologist at the University of Freiburg. He succeeded Rickert. Heidegger became his closest confidante as an assistant (successor to Edith Stein ) and private lecturer from 1919 . Husserl granted him insights into his research, and Heidegger, looking back, highlighted the benefits that this close relationship had for him. From 1920 the friendly correspondence with the philosopher Karl Jaspers began . In order to be able to receive an extraordinary professorship in Marburg, Heidegger drew up a sketch of an Aristotle book for Paul Natorp in 1922 , the so-called Natorp report, which anticipated many thoughts from being and time . Heidegger described his philosophy, which was just emerging here, as expressly atheistic , but at the same time declared in a footnote: A philosophy that sees itself as a factual interpretation of life must also know that this means a "lifting of hands against God".

During the Weimar Republic , Heidegger broke with the "system of Catholicism" and devoted himself exclusively to philosophy.

Heidegger was shaped by its deep roots in rural life in southern Germany. From Freiburg he discovered the southern Black Forest for himself. In the landscape between Feldberg and Belchen he saw intact nature, a healthy climate and idyllic villages. In Todtnauberg , Elfride Heidegger bought a piece of land from her last savings and had a hut built by the master carpenter and farmer Pius Schweitzer according to his own plans, which was available on August 9, 1922 and only received an electricity connection in 1931. Heidegger wrote many of his works there. He couldn't make friends with the hectic cities in his whole life.

“All of my work [...] is carried and guided by the world of these mountains and farmers. [...] as soon as I get back up, the whole world of earlier questions intrudes in the first hours of being a hut, in the shape in which I left them. I am simply put into the natural vibration of work and am basically not in control of its hidden law. "

During an extraordinary professorship at the University of Marburg from 1923 to 1927, he became friends with the theologian Rudolf Bultmann . Heidegger was already considered an outstanding teacher among students. Karl Löwith , Gerhard Krüger and Wilhelm Szilasi were among his students . The young Hannah Arendt also attended lectures from him, as did her later first husband Günther Anders and their mutual friend Hans Jonas . In a radio broadcast in 1969, she recalled the fascination that emanated from his teaching activity at the time: “Heidegger's fame is older than the publication of Sein und Zeit [...] college transcripts [went] from hand to hand [... and] the name traveled all over Germany like the rumor of the secret king. [...] The rumor that lured [the students] to Freiburg to the private lecturer and a little later to Marburg said that there is someone who has really achieved the cause that Husserl had proclaimed. "

In 1927 his major work, Sein und Zeit, was published . The book was published as an independent volume in Edmund Husserl's Yearbook for Philosophy and Phenomenological Research series. The early lectures accessible through the complete edition make the genesis of Being and Time very easy to understand. It turns out that the fundamental ideas essential for being and time emerged in Heidegger's work early on . In 1928 he succeeded Husserl's chair in Freiburg. He gave his inaugural lecture on the topic: What is metaphysics? In addition, his lectures and the Davos disputation with Ernst Cassirer on Immanuel Kant on the occasion of the II. International University Courses in 1929 made Heidegger well known.

National Socialism

This section deals with the historical events during the time of National Socialism . For Heidegger's relationship to National Socialism, see the article → Martin Heidegger and National Socialism .

After coming to power in 1933, Heidegger enthusiastically participated in what he saw as the National Socialist revolution. On April 21, 1933 he became rector of the Freiburg University . He was proposed for the office by his predecessor Wilhelm von Möllendorff , who had become untenable as a Social Democrat and had resigned the day before - presumably under pressure from the Nazi regime. Heidegger, who had already elected the NSDAP in 1932, joined it on May 1, 1933 and remained a member until the end of the war.

In his rector's speech on May 27, 1933 , entitled The Self-Assertion of the German University , the word came from the “greatness and magnificence of this awakening”. The speech had National Socialist connotations and has caused a lot of negative attention to this day: In it Heidegger called for a fundamental renewal of the university. With philosophy as the center, it should regain its wholeness, similar to that in antiquity. The relationship between professors and students should correspond to that of “leaders” and “followers”. He also emphasized the need for ties to the so-called “ national community ” and the important role of the university in the training of cultural leaders of the people.

During his rectorate, Heidegger took part in the propaganda and conformity policy of the "movement" and gave a speech on the burning of books , which he forbade, however, according to his own statements, to be held in Freiburg. During his rectorate in 1933, Heidegger actively campaigned for the whereabouts of Jewish colleagues such as the chemist Georg von Hevesy and the classical philologist Eduard Fraenkel, as well as for the Jewish teachers and professors at the University of Freiburg Jonas Cohn, Wolfgang Michael and Heidegger's assistants Dr. Werner Bock. According to his own statement, however, he prohibited the " Jews' poster " from being displayed at the university . But he did nothing to curb the increasing anti-Semitic resentment at the university. He denounced two colleagues, Eduard Baumgarten , with whom he had a technical dispute in 1931, and Hermann Staudinger . In 1933 Heidegger organized a science camp in Todtnauberg for lecturers and assistants who were supposed to be brought closer to the "National Socialist upheaval in higher education". On November 11, 1933, he signed the German professors' confession of Adolf Hitler in Leipzig and gave a keynote speech at the event. He also signed the election call for German scientists behind Adolf Hitler on August 19, 1934.

On April 27, 1934, Heidegger resigned from the office of Rector, as his university policy did not find enough support either at the university or by the party. The reason was not (as he later presented himself) that he did not want to support the National Socialist university policy, rather it did not go far enough for him: Heidegger was planning a central teaching academy in Berlin. All future German university lecturers should receive philosophical training in this academy. The National Socialist Marburg psychologist Erich Jaensch wrote a report in which he described Martin Heidegger as "one of the greatest muddled minds and most unusual loners" that we have in university life ". Heidegger's ambitious plans failed, and he withdrew from National Socialist university politics. A lecture, which was planned under the title The State and Science and to which leading party members had come with certain expectations, was canceled without further ado. Heidegger to the auditorium : "I read logic ." In addition, Heidegger reported that after his resignation from the rectorate he had been monitored by the party and that some of his writings were no longer available in stores or were only sold under the counter without a title page.

In May 1934, Heidegger was, together with Carl August Emge and Alfred Rosenberg, a founding member of the Committee for Legal Philosophy at the National Socialist Academy for German Law , headed by Hans Frank , and belonged to the committee until at least 1936.

From 1935 to 1942 Heidegger was a member of the Scientific Committee of the Nietzsche Archives . However, he resigned in 1942 without giving any reasons. His criticism of the historical-critical edition , which he should have overseen there, he later clearly presented in his two-volume Nietzsche book.

In November 1944 he was called up to work on the entrenchments as part of the Volkssturm , but released again in December due to the intervention of the university. After bombing raids on Messkirch, Heidegger brought his manuscripts to Bietingen. The Philosophical Faculty of Freiburg University was temporarily relocated to Wildenstein Castle , where Heidegger saw the end of the war.

As part of the denazification process, the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Freiburg had prepared a report in September 1945, which advocated Heidegger's retirement with limited teaching authorization. The member of the clean-up commission, Adolf Lampe , protested against this, as did Walter Eucken and Franz Böhm , and so the case was reopened on December 1, 1945. Heidegger then asked for an expert report from Karl Jaspers , which he wrote in letter form on December 22, 1945. However, Jaspers considered Heidegger to be intolerable due to his involvement in National Socialism as part of the teaching body and suggested “suspension from teaching for a few years”. On January 19, 1946, the Senate decided on this basis and on the basis of the new commission report by Chairman Constantin von Dietze to withdraw the license to teach . On October 5, 1946, the French military government also made it clear that Heidegger was not allowed to teach or take part in any university events.

The teaching ban ended on September 26, 1951 with Heidegger's retirement. The reception of Heidegger's works is still heavily burdened by his Nazi past, his later silence on it and various anti-Semitic statements in the black books .

Late years

In 1946 Heidegger suffered a physical and mental breakdown and was treated by Victor Freiherr von Gebsattel . After he recovered, Jean Beaufret contacted him with a letter. In it he asked Heidegger how, after the events of World War II, the word humanism could still be given meaning. Heidegger replied with the letter about "humanism" , which met with a great response: Heidegger was back on the philosophical stage. Ernst Jünger , whose book Der Arbeiter Heidegger had strongly influenced him (he adopted the term “total mobilization” in the articles ), came to visit Todtnauberg in 1949.

With his retirement, Heidegger regained his professorial rights. He immediately announced a lecture and read again for the first time in the winter semester at Freiburg University. His lectures were very popular and, like his writings, received a wide response. He also gave lectures on a smaller scale, for example in 1950 at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences on "Das Ding" and in 1951 at the Darmstadt Talks of the German Werkbund on the subject of "Building - Living - Thinking". In 1953 Heidegger posed the “question about technology” to the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts , and in 1955 he gave the lecture “Serenity” at the Conradin Kreutzer celebration in Meßkirch .

In 1947 Heidegger was contacted by the Zurich psychotherapist Medard Boss , from which a lifelong friendship grew. He held the "Zollikoner seminars" at the home of Medard Boss 1959-1969, of which the basis of the Swiss psychiatrist one of Heidegger's analysis of existence ajar Daseinanalysis developed.

In 1955 René Char met the German philosopher in Paris. René Char invited Heidegger to travel to Provence several times . So it came to the seminars in Le Thor in 1966, 1968, 1969 and in Zähringen in 1973, an exchange of poets and thinkers.

On his 70th birthday on September 26, 1959, he was granted honorary citizenship in his hometown of Messkirch. On May 10, 1960, Heidegger received the Johann-Peter-Hebel-Prize in Hausen im Wiesental . Since 1958 he was a full member of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences .

Heidegger's thinking developed worldwide. Mention should be made in this context of the numerous translations of Being and Time , including into Japanese. Heidegger also had a lasting effect on the Far Eastern philosophers. Hannah Arendt supported the publication of his work in the USA. On the 500th anniversary of the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg in 1957, he gave the keynote lecture “The Sentence of Identity”. In addition to an interview for the news magazine Der Spiegel in 1966, he also gave occasional television interviews, such as Richard Wisser in 1969 .

Significant for him were the two trips to Greece in 1962 and 1967, the impressions of which he captured in the stays , the trips to Italy in 1952 and 1963 with Medard Boss as well as his repeated holidays in Lenzerheide with him. In 1967 Heidegger met the poet Paul Celan , whom he valued in Freiburg , who was there for a reading. The explosiveness of the meeting resulted from the biography of Celan, whose parents had been murdered as Jews by the National Socialists and who therefore apparently expected an explanation from Heidegger for his behavior in the period after 1933, which he did not receive. Nevertheless, both drove together to Todtnauberg, where Celan signed the guest book. Later he sent the poem Todtnauberg to Heidegger , in which he expressed "a hope, today ..." "... on a thinker / coming / word / in the heart".

Heidegger had prepared the publication of his complete edition himself, the first volume of which appeared in 1975. Heidegger died on May 26, 1976 in Freiburg. In accordance with his wishes, he was buried on May 28, 1976 in Messkirch, his birthplace. At his funeral, his son Hermann Heidegger read poems by Holderlin that his father had chosen. The funeral oration was given by one of his philosophical descendants, Bernhard Welte .

Heidegger was convinced that the "understanding appropriation" of a thoughtful work had to be carried out on its content - the person of the thinker thus faded into the background. Therefore, autobiographical data are extremely sparse and much can only be inferred through letters or reports from contemporaries. The little importance Heidegger ascribed to the biography of a thinker can be seen in the words with which he once opened a lecture on Aristotle: “Aristotle was born, worked and died. So let's turn to his thinking. "

Thinking as a way

Questions, not answers

In the text “Martin Heidegger is eighty years old” in 1969, Hannah Arendt took a stand in favor of Heidegger's philosophy. Politically, like Plato, he was one of those philosophers who trusted tyrants or leaders . She summed up his life's work: “Because it is not Heidegger's philosophy - of which one can rightly ask whether it even exists - but Heidegger's thinking that has so decisively shaped the spiritual physiognomy of the century. This thinking has a piercing quality peculiar to itself, which, if one wanted to grasp and prove it linguistically , lies in the transitive use of the verb 'think'. Heidegger never thinks 'about' anything; he thinks something. "

Arendt's quote makes it clear what Heidegger was about in philosophy: Thinking itself is already being carried out, it is practice, and it is less about providing answers to questions than about keeping the questioning itself awake. Heidegger therefore rejected both historical and systematic “philosophy learning”. Rather, the task of philosophy is to keep these questions open; philosophy does not offer certainty and security, but “the original motive of philosophy [arises] from the uneasiness of one's own existence”.

The central position of questions in Heidegger's work is due to the fact that he interpreted the history of philosophy primarily as a history of the concealment of fundamental questions. In doing so, philosophy has not only forgotten the basic questions - the question of being - but also the fact that it has forgotten. The aim of asking is not to get an answer, but rather to uncover what would be further forgotten without it. For Heidegger, asking questions became an essential feature of thinking: "Asking is the piety of thinking."

Access to the work and linguistic barriers

Nevertheless, in spite of this openness to questions, access to Heidegger's work remains extremely difficult. This is not least due to Heidegger's peculiar, creative language - a diction that is particularly easy to parody due to its inimitable quality . After a lecture in 1950, a “ Spiegel ” journalist wrote ironically that Heidegger had “the annoying habit of speaking German”.

Heidegger's language is - especially in Being and Time - shaped by neologisms , and he also invented verbs such as not , lichten , and beings . Constructions such as “ nothing does not do ” (in: What is metaphysics? ), Owed to Heidegger's attempts to think things as themselves: It is nothing itself that does not do anything. No metaphysical concept should be used to explain it. With such violent semantic duplication, Heidegger wanted to overcome the theoretically distant gaze of philosophy and jump to the ground on which we - even if we do not see it - have always been standing in our concrete lives.

In his late work, Heidegger turned away from neologisms, but instead loaded words from everyday language semantically until they were incomprehensible, so that their meaning can only be understood in the overall context of his treatises. Heidegger was sharply attacked because of his use of language: Theodor W. Adorno's polemical work Jargon of Authenticity is the most prominent . Heidegger did not use this jargon for his own sake, but wanted to break away from the philosophical tradition that language and content were inseparable.

For the reader, this means that he must first acquire Heidegger's vocabulary, indeed become an inhabitant of this discourse , if he then wants to deal with Heidegger's thinking from within. This is exactly what Dolf Sternberger criticized: One can only answer Heidegger's terminology using Heidegger's terms. In order to understand Heidegger's thinking, there is a middle ground: taking his language seriously and at the same time avoiding just repeating a jargon. Heidegger himself has therefore repeatedly pointed out how important it is not to “understand his statements as what is in the newspaper.” Instead, his terms are intended to open up a new area by referring to what is already there, but Always point out what has been overlooked: What they formally indicate , everyone should ultimately be able to find in their own direct experience. "The meaning of these terms does not mean or say directly what it refers to, it only gives an indication, an indication that the understanding of this context is called upon to transform himself into existence."

Ways, not works

What is striking about Heidegger's writings is the rather small number of large and complete treatises. Instead, there are mainly small texts and lectures - a form that seemed more suitable to him to convey his thinking, especially since it stands in the way of an interpretation of this thinking as a philosophical system.

The fact that Heidegger's thinking and philosophizing move and thereby cover a path is shown by the titles of works such as Wegmarks , Holzwege and Unterwegs zum Sprach . Thinking becomes a way and a movement, which is why Otto Pöggeler also speaks of Heidegger's way of thinking . Heidegger's thinking is not so much to be understood as a canon of opinions, but offers different approaches to the “essential questions”. In the notes he left behind for a preface to the complete edition of his writings that was no longer finished, Heidegger noted: “The complete edition is intended to show in different ways: a journey in the path of the changing question of the ambiguous question of being. The complete edition is intended to guide you to take up the question, to ask and, above all, to ask more questioningly. "

Early phenomenology: hermeneutics of facticity

After a rather conventional dissertation and habilitation, Heidegger's confidence in the school philosophy of the time was shaken , especially by thinkers such as Kierkegaard , Nietzsche and Dilthey . They opposed metaphysics and its search for a timeless truth against history with its coincidences and the changeability of moral values and reference systems. Heidegger turned his back on purely theoretical concepts of philosophy. He was increasingly interested in how concrete life can be described phenomenologically , as life that is given in its historically evolved factuality, but which did not necessarily have to be. With this approach, called the phenomenological hermeneutics of facticity , Heidegger tries to show life contexts and experiences , not to explain them . The aim of this phenomenological approach is not to make one's own life an object and thus understand it as a thing, but to push it through to the fulfillment of life . Heidegger explains this as an example in 1920/21 in the lecture “Introduction to the Phenomenology of Religion” using the words of the Apostle Paul: “The Lord's day comes like a thief in the night.” For Heidegger, Heidegger expressed an attitude towards life in the apostle's early Christian life that does not attempt to make the unavailable future available through determinations or calculations. It is the constant openness to the suddenly occurring event, the directly lived life, that Heidegger opposes a theoretical consideration of life.

After the First World War, Heidegger, as Husserl's assistant, worked particularly intensively on his phenomenological method. Husserl granted him insights into as yet unpublished writings and hoped to have found a pupil and crown prince in Heidegger. Heidegger, however, pursued his own interests, and Husserl also remarked that Heidegger “was already unique when he was studying my writings.” It was above all Dilthey's assumption of the historical development and contingency of every relationship to the world and to oneself that prompted Heidegger to do so led to reject Husserl's concept of absolutely valid beings of consciousness: “Life is historical; no dismemberment into essential elements, but context. ”Based on this view of life as a fulfillment, Heidegger rejected Husserl's phenomenological reduction to a transcendental ego that was merely apperceptive to the world . These early considerations, together with suggestions from Kierkegaard's existential philosophy, culminated in Heidegger's first major work, Being and Time .

"Being And Time"

The question of being

The theme of the work, published in 1927, is the question of the meaning of being . This question had already preoccupied Plato . Heidegger quoted him at the beginning of the investigation: “Because you have obviously long been familiar with what you actually mean when you use the expression 'being', but we once believed we understood it, but now we are embarrassed . "Even after two thousand years, so Heidegger, this question is still unanswered:" Do we have an answer today to the question of what we actually mean by the word "being"? Not at all. And so it is important to ask the question of the meaning of being again. "

Heidegger asked about being . If at the same time he searched for its meaning, then he presupposes that the world is not a formless mass, but that there are meaningful references in it . So being is structured and has a certain uniformity in its diversity. For example, there is a meaningful relationship between hammer and nail - but how can this be understood? “From where, that is: from which given horizon do we understand things like being?” Heidegger's answer to this was: “The horizon from which things like being can be understood at all is time .” The meaning of time for being became According to Heidegger, it has not been considered in any previous philosophy.

Critique of the traditional doctrine of being

According to Heidegger, the occidental doctrine of being has given various answers in its tradition as to what it means by “being”. However, she never posed the question of being in such a way that she inquired about its meaning, that is, examined the relationships inscribed in being. Heidegger criticized the previous understanding that being has always been characterized as something that is individually, something that is present, i.e. in the temporal mode of the present . Regarded as something that is merely presently present , what is present is stripped of all temporal and meaningful references to the world: the determination that something is cannot be understood as what something is.

When determining being as, for example, substance or matter , being is only presented in relation to the present: what is present is present, but without any reference to the past or future. In the course of the investigation, Heidegger tried to show that, in contrast, time is an essential condition for an understanding of being, since it - to put it simply - represents a horizon of understanding within the framework of which things in the world can only develop meaningful relationships between one another. The hammer, for example, is used to drive nails into boards in order to build a house that offers protection from coming storms. So it can only be in the overall context of a world with temporal relations understand what the hammer out of an existing piece of wood and iron is .

The way out of the philosophical tradition to determine what something is, ontological reductionism , also represented a failure for Heidegger when he tried to trace everything back to a primal principle or to a single being. This approach, criticized by Heidegger, enables onto-theology , for example , to accept a highest being within a linear order of being and to equate this with God.

Ontological difference

A fundamental ontological investigation should correct this mistake in previous philosophical thinking, not focusing on the importance of time for the understanding of being . Heidegger wanted to place the ontology on a new foundation in Being and Time . The starting point for his criticism of traditional positions in ontology was what he called the ontological difference between being and being.

In Being and Time , Heidegger roughly referred to being the horizon of understanding on the basis of which an inner-worldly being encounters. Every understanding relationship to inner-worldly beings must move in such a contextual horizon in which what is first becomes apparent. So when we encounter something, we only ever understand it through its meaning in a world. This relationship is what defines its being. Every single being is therefore always already transcended, i.e. H. surpassed and placed as an individual in relation to the whole, from where it first receives its significance . The being of a being is therefore that which is given in the “stepping over”: “ Being is the transcendens par excellence. [...] Every opening up of being as the transcendens is transcendental knowledge. "

If one starts from the ontological difference, then each individual being is no longer understood merely as something that is present at present. Rather, it is topped with respect to a whole: In view of something in the future and in its origin from the past its being is essentially time- determined.

Language difficulties

Being as such a temporal horizon of understanding is therefore the always athematic prerequisite that individual beings can encounter. Just as the giving and the giver are not contained in the given, but remain unthematically, being itself never becomes explicit.

However, being is always the being of a being, which is why there is a difference between being and being, but both can never appear separately from one another. Being thus shows itself to be the closest, because in dealing with the world it always precedes and goes along with it. As an understanding of the horizon , however, it cannot actually be addressed - because a horizon can never be reached. If, in spite of everything, being is raised linguistically to the topic, it is at the same time missed. Since most of the terms in everyday language and philosophy refer solely to things in the world , Heidegger found himself faced with a linguistic hurdle in Being and Time . This can be seen in the noun “being”, which represents being as being within the world. In order not to have to tie in with metaphysically loaded concepts, Heidegger created many neologisms in Sein und Zeit .

Hermeneutic Phenomenology

Heidegger therefore starts from the assumption that being can neither be determined as an existing thing nor as a mass without structure or connection. The world in which we live, but rather provides a network of relationships of meaningful references are. Now the investigation for Heidegger was not simply a paradigm fix if they really a phenomenological should be, because the phenomenology trying circumstances have not deductively to declare . Since he has always lived in a world, man cannot go back beyond this given horizon of understanding, he can only try to understand it and highlight individual moments. Heidegger therefore chose a hermeneutic approach.

The hermeneutic circle in being and time

In order to be able to understand the meaningful references in the world, according to Heidegger, a hermeneutic circle must be run through, which brings a better understanding to light with each run. The movement of this circle runs in such a way that the individual can only be understood in relation to the whole, and the whole can only be seen in the individual. If the process of understanding is only possible by going through a circle, it is still questionable where this circle should begin. Heidegger's answer to this: the starting point is the person himself, because it is obviously he who asks the question about the meaning of being.

Heidegger calls the being of the human being Dasein , the investigation of this Dasein fundamental ontology . The question about the meaning of being can only be answered by Dasein , because Dasein alone has a prior understanding, as is a necessary prerequisite for any hermeneutical investigation. Heidegger calls this pre- understanding of being the understanding of being . It happens to all people when they understand the different ways of being of things: We don't try to talk to mountains, we treat animals differently than we do with inanimate nature, we don't try to touch the sun, etc. All these self-evident behaviors are based on interpretations about how and what things are . Since Dasein has this fundamental characteristic, that is to say, the human being has always been let into a pre-reflective horizon of understanding, Heidegger consequently directs his questioning to Dasein.

Due to this fundamentally hermeneutic orientation, he no longer assumes a cognitive subject who (as in Kant, for example ) mainly perceives bodies in space and time. Rather, Dasein is an understanding that has always been integrated into a world. Heidegger did not choose a special existence as the point of entry into the circle, but existence in its everyday life . His aim was to bring the philosophy of transcendental speculation back to the bottom of the common world of experience. The soil itself, as "down-to-earth" and "bottomlessness", together with terms such as "rootedness" and the "uprooted" existence of the "man", was given a meaning that is epistemologically difficult to grasp, which makes it long Debate about it was triggered.

According to Heidegger, two steps of the hermeneutic circle are required for this: In the first, it is to be examined how the meaning relationships in the world represent for existence. The world is therefore described phenomenologically. Heidegger did this using the context of tools such as the hammer mentioned above. In the second step, an “existential analysis of existence ” takes place , i.e. the investigation of the structures that make up existence such as language, sensitivity, understanding and the finiteness of existence. If the relationship between Dasein and world is properly understood in this way, it must at the same time be grasped ontologically if being is to be determined .

Fundamental ontology

On the way to a new ontology

In order to advance the overcoming of the modern ontology based on the subject-object schema , Heidegger introduced the concept of being- in-the-world . It should show the basic togetherness of existence and the world . The world does not mean something like the sum of all that is, but a meaningful totality, a totality of meaning in which things relate meaningfully to one another. Went the transcendental philosophy of Kant from a self-sufficient, resting in itself subject whose connection will be manufactured with the outside world had so existence is in Heidegger one hand always existed world, on the other hand is the world in general only for existence. The concept of being-in-the-world encompasses both aspects. For Heidegger, the world is not a thing, but a web of relationships over time. He calls this happening of the world the worldliness of the world. It can only be understood in connection with existence. So what the hammer is as a hammer can only be understood in relation to the existence that needs it. So being is inscribed with a meaning and “meaning is that in which the intelligibility of something is.” The meaning of being and existence are mutually dependent: “Only as long as existence is , that is, the ontic possibility of understanding being, 'there is' being . ”Heidegger represented neither a metaphysical realism (“ things exist as they are, even without us ”) nor an idealism (“ the spirit creates things as they are ”).

The analysis of Dasein should provide the foundation for a new ontology beyond realism and idealism. In Being and Time, Heidegger highlights various structures that determine Dasein in its existence , i.e. in its life . He called these existentials : Understanding , sensitivity , speech are fundamental ways in which existence relates to itself and the world. The existentials are moments of a structural whole that Heidegger defined as care . The being of existence thus proves itself to be care: man is care. However, Heidegger wants to keep this definition of human existence as worry free from secondary meanings such as “concern” and “misery”.

If the existence of Dasein turns out to be a worry, then the world can be understood from here: the hammer and other tools are used to build houses. The various tools are by order-to connected, that ultimately in order-will ends of existence, this be makes things because it is himself and his fellow man makes . The scientific understanding of the world and the understanding of nature ultimately arise from existence as a concern for Heidegger.

Temporality and Existence

Since Dasein as a concern is obviously always determined from a past and is directed towards the future, the second part of Being and Time is followed by a new interpretation of the existentials under the aspect of time. For Heidegger, time does not initially turn out to be an objective, physical process, but rather the temporality inscribed in existence that is closely related to care. The close relationship between time and worry can be seen, for example, in everyday expressions of time such as “until then it's a walk”. According to Heidegger, care-related time is ontologically primary. It is only out of everyday dealing with time that Dasein develops an objective (scientific) time with which it can calculate and plan and which can be determined by clocks. However, all planning and arithmetic remain tied to concern.

Turning away from "being and time"

For various reasons, Sein und Zeit remained a fragment of which only the first half is available. Although Heidegger was able to overcome many problems of the traditional ontology with the new ontological thinking, which was based on the relationship between Dasein and Being, his approach only led to relatively limited possibilities for philosophical understanding. This is mainly due to the care structure and the temporality inscribed in existence . There was thus the danger that all aspects of human life should only be interpreted from these points of view. Heidegger himself warned against overestimating temporality, but this was not convincing.

Heidegger had also linked his concept of truth to Dasein in Being and Time : The world has always been opened up to Dasein in practical use of it . With this formulation he wanted to assign an ontological dimension to his understanding of truth: the world clears only for Dasein , only for it is the world, and from here it is also determined what beings are. It becomes clear how strongly the care structure centers the world and things in terms of time and content around the for-for and for-sake , i.e. around the practical needs of existence. From this point of view, historical upheavals in the understanding of self and the world and the passivity of man in the course of history are difficult to understand. In addition, there was the difficulty of distinguishing oneself from the language of metaphysics, as Heidegger wrote in retrospect in 1946 in his letter about "humanism" .

The reasons mentioned finally prompted Heidegger to turn away from the fundamental ontological approach. So "the path through being and time was an inevitable and yet a wrong path - a path that suddenly ends". This was followed by a rethink for Heidegger, which he called a turn .

Dealing with Kant

The announced second part of Being and Time was to begin with Kant's concept of time, and after the publication of the first part, Heidegger immediately turned to dealing with Kant. First it took place through the lectures of the winter semester 1927/28 in Marburg, which Heidegger called the phenomenological interpretation of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason . In this reading of Kant's main work, interpreted and explained with his own terminology, Heidegger ended up aiming at the question of subject and time. On the other hand, in the Kant lectures in Riga and on the occasion of the Second Davos University Days in spring 1929, as well as in the disputation held there with Ernst Cassirer, the topic of finitude came to the fore, which was also discussed in Heidegger's so-called “Kant book”, Kant and the problem of metaphysics remained central. At the same time, the themes of subject and finitude cannot be limited to one of the works mentioned in Kant, since the transitions between them are fluid. Heidegger's discussion of Kant during that period is concluded with the lecture The Question About the Thing from 1934/35.

The phenomenological interpretation of the Critique of Pure Reason

In the preface to the Critique of Pure Reason , Kant distinguishes the first and objective from the second and subjective part of the transcendental deduction and, according to Heidegger, "simply fails to recognize the inner connection between the objective side of the deduction and the subjective - even more: he fails to recognize, that precisely the radical implementation of the subjective side of the task of deduction also takes care of the objective task. ”Heidegger adds the corresponding requirement to this interpretation in the Marburg lectures and states:“ Kant does not go this radical path here ”. This heralds a pattern of interpretation to which he comes back in the Kant book , where it says: “The transcendental deduction is in itself necessarily objective-subjective at the same time. Because it is the revelation of the transcendence, which forms the essential turn to an objectivity for a finite subjectivity in the first place. ”But since Kant avoided“ the vastness of a complete theory ”of the analysis of the“ three subjective cognitive forces ”, for him“ the Guiding the subjectivity of the subject in the constitution and the characteristics offered by the traditional anthropology and psychology. "Heidegger, on the other hand, sees in the Kantian transcendental imagination first" the central function (...) in the enabling of experience ", and finally also the" uniform root (...) for intuition and thinking ", which forms the" universal time horizon. "

The unique mention of time as a form that the mind sets for itself, inserted in the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason (B 68), then takes on a central role for Heidegger as "pure self-affection" and "a priori self-approach" of time in the interpretation of the self: "The original temporality is what the original act of the self and its self- action are based on , and it is the same temporality that enables self-identification of the self at any time." Heidegger's objection arises that Kant uses this identification "only from the present "understand," in the sense that the ego can identify itself as the same in every now. "So it remains only with a basically" timeless, punctiform ego ", which through an" ontological interpretation of the wholeness of existence " , through the " anticipation " and the " ability to be " must be overcome.

Although Heidegger admits in the Marburg lectures that "Kant neither sees the original, uniform character of the productive imagination with regard to receptivity and spontaneity", "nor takes the further radical step of recognizing this productive imagination as the original ecstatic temporality", he interprets it in a philologically quite dubious way as the “ecstatic basic constitution of the subject, of existence itself”, which “releases pure time from itself, thus containing it in itself as far as possible”. The Kantian transcendental imagination is thus the " original temporality and therefore the radical faculty of ontological knowledge". With the reduction to the self-affection of time and the imagination determined by it as the one “root” of knowledge, Heidegger's interpretation moves away from the Kantian dualism and rather approaches the solipsism that followed Fichte on Kant.

The Kant book and finiteness

In Being and Time , in the Marburg Kant lectures and also in the Kant book , Heidegger named the Critique of Pure Reason as a reference for his thinking in the sense of "confirming the correctness of the path I was looking for". Nonetheless, he had stated in Kant “the lack of a thematic ontology of Dasein”, that is, that of a “prior ontological analysis of the subjectivity of the subject”. Kant and the problem of metaphysics , in which the three lectures from Riga and Davos were summarized and expanded by a fourth chapter, should remedy this and through a "destruction of the guide" of the "problem of temporality (...) the schematism chapter and from there interpret the Kantian doctrine of time ”. It seemed to Heidegger to be necessary to bring the “question of finitude to light with the intention of laying the foundation of metaphysics”, because: “The finitude and the peculiarity of the question about it only fundamentally decide on the inner form of a transcendental one 'Analytics' of the subjectivity of the subject. "

To the finitude of existence

Since the Davos lectures , human finiteness has moved to the fore as a topic in general in Heidegger's thinking: “Finiteness was never mentioned in the introduction to Being and Time, and it remained discreetly in the lectures before Being and Time Background before it becomes the all-determining topic at the end of the twenties. ”In the second of the three Davos lectures held in spring 1929 on Kant's Critique of Pure Reason and the task of laying the foundation for metaphysics , in which Heidegger“ explains the train of thought of the first three sections of the "The essence of finite knowledge in general and the basic characters of finiteness" were decisive for "understanding the implementation of the foundation" of metaphysics. Formulated in his own words, Heidegger asks: "What is the inner structure of existence itself, is it finite or infinite?"

He does not see the question of being first, but rather that of the "inner possibility of understanding being", i.e. also of "the possibility of the concept of being", as a prerequisite for deciding the other question, which is also not related to the ancient philosophy of being had been clarified, namely, "whether and in what way the problem of being has an inner relation to finitude in man". Even in a thoroughly Kantian line of thought, Heidegger presupposes that existence means “dependence on beings”, but that this itself is “as a kind of being in itself finitude and as this only possible on the basis of the understanding of being. Such things as being only exist and must exist where finitude has existed. (...) The finitude of existence in him is more original than man. "

Finiteness as a problem base of the KrV

As Heidegger himself admits, the foundation of human finiteness as the “problem base” of Kant's main work is “not an explicit topic” - literally the term “finitude” is not mentioned in the KrV - and thus this emphasis belongs to the “overinterpretation of Kant ", In which" the criticism of pure reason is interpreted in the perspective of the question of 'being and time', but in truth a question alien to Kant, albeit a conditional one. "For Heidegger, finitude is" primarily not that of knowledge , but that is only an essential consequence of thrownness. ”Rather,“ ontology is an index of finitude. God doesn't have them. And that man has the exhibitio is the sharpest argument of his finitude. Because ontology only needs a finite essence. ”With regard to the possibility of knowledge and the question of truth, Heidegger already interprets in the Davos disputation with Cassirer the later presented in the essence of human freedom ,“ in this finitude existing (...) meeting of the conflicting "To:" Due to the finiteness of man's being-in-the-truth, there is at the same time being-in-the-untruth. The untruth belongs to the innermost core of the structure of existence. (...) But I would say that this intersubjectivity of truth, this breaking out of the truth about the individual himself as being-in-the-truth, already means to be at the mercy of being itself, to be put in the possibility of it to design yourself. "

The emphasis on finitude as a way of being of existence raised the critical question of how the “transition to the mundus intelligibilis ” is possible in the Davos disputation , in the realm of mathematical truths as well as that of the ought. Cassirer asked whether Heidegger “wanted to renounce all of this objectivity, this form of absoluteness that Kant represented in the ethical, theoretical and critical of judgment”: “Does he want to withdraw entirely to finite essence, or if so not, where is the breakthrough to this sphere for him? ”Heidegger's answer of a“ finiteness of ethics ”and a finite freedom in which man is placed before nothing and philosophy has the task of giving him“ in all his freedom nothing to make his existence evident ", is seen in retrospect as a" sign of the weakness in which Heidegger finds himself after being and time because he is not able to carry out his fundamental ontological project. "

Heidegger closes the Kant book with around twenty mostly rhetorical questions in which the subject areas of subjectivity, finitude and the transcendental essence of truth are named. So he asks whether the transcendental dialectic of the KrV is not concentrated “in the problem of finitude” and whether the “transcendental untruth is not positively justified in terms of its original unity with the transcendental truth from the innermost essence of finitude in existence” and adds: “ What is the transcendental essence of truth anyway? ”In the Kant book , Heidegger fails to provide answers, but with the questions he outlines the draft of his studies for the following years.

The rethinking in the 1930s: The turn

The change in the understanding of truth

Between 1930 and 1938, Martin Heidegger's path of thought saw a rethink that he himself described as a turn . He turned away from his fundamental ontological thinking, and a history of Being approach. After the turning point, he was no longer concerned with the meaning of being or its transcendental horizon of interpretation (time), but instead referred the talk of being as such to how being by itself both reveals itself and hides itself . Heidegger was concerned with a new, non-objective relationship between man and being, which he describes in the “Letter of Humanism” with the expression “Shepherd of Being”. This also made him a forerunner of new ecological thinking.

Of the essence of truth ...

Being and time was determined by existential truth : Dasein has always somehow discovered the reference context of the inner-worldly in the pre-reflective relation to the world that arises in the practical handling of things ; it also has a pre-thinking understanding of itself and the inevitability of having to make decisions, that is, to have to lead one's life. Heidegger called this association of truth and existence, which is necessary for existence, to the truth of existence . With the turn he shifted this focus. For an understanding of the relationship between the world and the self, in his view, not only the structure of our existence is important, but also how the world, being, shows itself to us . It therefore also needs to be open to the open, unconcealed. Heidegger carried out this expansion of his concept of truth in 1930 in the lecture “On the essence of truth”. It is true that he still understood truth - as in Being and Time - as unconcealment ; However, for Heidegger it became clear that man cannot create this unconcealment on his own.

... to the truth of the essence

Being reveals itself to man not only in relation to his existence, but in manifold forms. Truth can happen through art, for example, as Heidegger described in his 1935 lecture “ The Origin of the Artwork ” . If a work of art expresses what was previously atrophy or hidden and raises it into awareness, then truth shows itself as a process: truth happens . In order to grasp this linguistically, Heidegger had to say: Truth is west ; for since what is only reveals itself in the process of truth as revelation , one cannot say “truth is.” The essence of truth is therefore its essence as a process. If, after the turn, truth is no longer rigidly bound to the already existing disclosure of the world and self through Dasein, this means a twofold: Truth becomes processual, and it can include provisions that are not understood in terms of pragmatically existing Dasein to let. This shift in the center of gravity is expressed in the reverse: the essence of truth becomes the truth of essence . Heidegger called his own rethinking a turn :

“By giving up the word meaning of being in favor of the truth of being, the thinking that has emerged from being and time will in future emphasize the openness of being itself more than the openness of existence [...] That means the 'turn' in which thinking finds itself turning more and more decisively to being than being. "

A-letheia: concealing and revealing being

So that being now shows itself in its unconcealedness , man is still required as a “clearing”: what is shows itself to him in different light (e.g. “everything is spirit / matter”, “the world” is created by God ”etc.). Heidegger's concept of truth is essentially ontological . For him it is about how people can actually see what is . All other determinations of truth, for example as telling truth (right / wrong), can only be linked to the fact that being has previously revealed itself to man in a certain way .

Heidegger's talk of uncovering and hiding, however, should not be confused with perspectival conceptions of truth. For on the one hand, unconcealment does not refer to individual beings which, due to the perspective, could only be seen from a certain side. On the other hand, Heidegger does not want to link the truth to sensual modes of knowledge such as that of seeing. Rather, truth is an overarching context of meaning, and so the talk of the unconcealedness of being means a whole , i.e. a world as a totality of meaning that opens up to people.

If Heidegger thought of the process of revealing being in terms of being itself, then for him it was always associated with concealment . This means that whenever being shows itself to be certain (e.g. "everything is matter"), it conceals another aspect at the same time. What is hidden, however, is not a concrete other determination of being (“everything is spirit”), but what is hidden is the fact that being has been revealed. Man therefore usually adheres to only the entborgenen being, however, forgets how this determination of being only even happen is. He merely corresponds to what has already been revealed and takes from it the measure of his actions and worries.

Even before being and time , Heidegger called this lack of the question of the “meaning of being” and the mere stopping at what is being, the oblivion of being . Because of the fundamental togetherness of concealment and revelation, this forgetting of being after turning no longer proves to be a failure on the part of man, but belongs to the destiny of being itself. Heidegger therefore also spoke of the abandonment of being . But now the human being is dependent on sticking to the being that has been revealed to him, because he can only orient himself to what is . With this dependence of man on being, a first determination of the essence of man is indicated. Stopping at what is, however, usually prevents people from experiencing a more primal access to their own being than that which belongs to revealing.

Despite this shift in emphasis between being and time and Heidegger's thinking after the turn, it is an exaggerated, distorted picture to speak of a heroic activism of existence in the early Heidegger and, in contrast, in the late Heidegger of a person condemned to passivity in relation to being. Such a comparison is based on only two aspects that were forcibly removed from the complete work, which Heidegger does not find in isolation.

Twisting metaphysics

Decline in the bottom of metaphysics

In Being and Time , Heidegger wanted to trace the ontology back to its foundation . In doing so, he remained largely in the field of classical metaphysics, seeing his efforts as a reform and continuation of ontology. After the turn, Heidegger gave up the plans to find a new basis for the ontology. Instead, he turned to What Is Metaphysics? the question of the basis of metaphysics : How does it come that metaphysics tries to determine being only from the point of view of being and towards being. in that it constitutes an ultimate or highest reason for the determination of all that is? With this question, Heidegger did not attempt to define beings himself again (this is the procedure of metaphysics), but rather examined metaphysics as metaphysics and the conditions of its procedure: How did the various interpretations of being come about through metaphysics? This question, which thematizes the conditions of metaphysics itself, was by definition closed to metaphysics , which itself only deals with beings and their being.

Deep thinking

Heidegger's goal was still to overcome metaphysics. First of all, it is necessary to reject metaphysical foundations . The investigation must not itself again bring paradigmatic presuppositions to its subject. A non-metaphysical thinking has to get along without final reasons. It has to bring itself into the abyss . Heidegger therefore called his thinking from then on as profound . From the abyss he now criticized his early philosophy: “Everywhere in being and time up to the threshold of the treatise Vom Wesen des Grunds is spoken and represented metaphysically and yet thought differently . But this thinking does not bring itself into the open of one's own abyss. ”Only from this abyss, from a position that knows no final reason, could Heidegger bring the history of metaphysics into view and interpret it.

Overcoming the subject-object schema

For Heidegger, the predominant philosophical current of modern philosophy was the philosophy of the subject, which began with Descartes . He rejected this subject-object schema for an unbiased interpretation of the history of philosophy. If metaphysics looks at the world and being as a whole and gives a definition of it (e.g. “everything is spirit”: idealism or “everything is matter”: materialism ), then the core of its approach is that it is what is before itself brings to determine it. Heidegger therefore spoke of representational thinking . The peculiarity of this imaginative thinking, however, is that it presents beings as an object for a subject and thus updates the subject-object split . In this way, however, metaphysics enthrones man as the measure of all things. The being has from now on the subject of human representations to be: Just what was put firmly-so-sure and asked, is also. For Descartes there is only that which can be mathematically described by humans.

The Kantian transcendental philosophy also placed the human being as the subject in the middle of all that existed, which Kant called the Copernican turn: it is not the subject that is based on the world, but the world is judged according to its ability to grasp. In the Critique of Pure Reason , Kant tried to give knowledge a secure ground through the categories of knowledge given to the pure understanding . For Kant, the aim was not to overcome metaphysics, but to create a secure foundation for subsequent speculations. Heidegger thus interpreted Kant as a metaphysician, that is the aim of his Kant book, where it says right at the beginning: "The following investigation has the task of interpreting Kant's Critique of Pure Reason as a foundation of metaphysics [...]". For Heidegger, Kant showed a metaphysical need for an ultimate justification: the subject ( reason ) should at the same time serve as the ground for all knowledge. It establishes what is known. The essence of metaphysics is that it presents being as an object for a subject and at the same time justifies it through the subject.

According to Heidegger, however, a paradox arises here . For if metaphysics only recognizes as justified what shows itself to the subject, but the subject cannot justify itself, then it is impossible for it to assure itself of its own ground. Even in reflexive self-assurance, in self-reflection, the subject only ever grasps itself as an object and thus fails precisely as a subject . The apparent impossibility of the double “oneself”, of having oneself in front of oneself, could only be overridden by a violent self-determination.

Twisting of metaphysics as part of the history of being

Since being has experienced various determinations through man in metaphysics, Heidegger comes to the conclusion that being itself has a history. Heidegger calls this history of being. The turn as a twist of metaphysics describes two things:

- On the one hand, the turn marks the turning away from metaphysics towards the investigation of the history of metaphysics, the history of being.

- At the same time, this turning away is itself an event in the history of being, that is, a new part of the history of being. Not because it continues the history of metaphysics, but because in an overall retrospective it brings it into view and seeks to conclude and overcome it. The overcoming of metaphysics remains related to that which has to be overcome. Heidegger therefore spoke of a twist .

In conversation with the great thinkers, not through hostile hostility, metaphysics should be brought to its limits: “That is why thinking, in order to correspond to the twisting of metaphysics, must first clarify the essence of metaphysics. To such an attempt, the twisting of metaphysics appears at first to be an overcoming that only brings the exclusively metaphysical representation behind it. […] But in the twisting the permanent truth of the apparently rejected metaphysics returns as its now appropriated essence. ”Looking back, Heidegger reflected on the first beginnings of Western philosophizing . In their twisting he looked for a different beginning .

First and different beginning

Heidegger tried to identify different epochs in the history of metaphysics. Referring to the philosophy of the early Greeks, he spoke of the first beginning that established metaphysics. He saw his own thinking and the post-metaphysical age he was striving for as a different beginning .

Failures of the first beginning

The first initial of the ancient Greeks divided for Heidegger in two events, the pre-Socratic thought and of Plato and Aristotle outgoing metaphysics. As Heidegger expressed himself in the term Aletheia (A-letheia as un-concealment), the early Greeks had an undisguised experience of being: they were still able to see this as unconcealment. For her, being as such was not yet at the center of interest, but rather the revelation for unconcealment . With Plato and Aristotle, however, according to Heidegger, a fall from this undisguised reference to truth occurred. Metaphysics began to predominate. Plato sought support in the ideas , Aristotle in the categories , whereby both were only interested in the determination of beings and, following the metaphysical need, tried to secure and fix it through ultimate reasons.

Decline to the pre-Socratics

With the other beginning, Heidegger wanted to go back behind Plato and Aristotle. The openness and early experiences of the pre-Socratics should be taken up again and made usable for future thinking. Heidegger did not understand the other beginning as a new beginning - since it was based on a constructive appropriation of the philosophical tradition and its failings - nor was the decline to the pre-Socratics determined by a romantic-restorative tendency.

On the other hand, the predominant aspect is the prospective aspect, which enables people to return to their being by knowing how to understand past history and contrasting the metaphysical interpretations of being with a new way of thinking. In order to make the difference between thinking at the beginning and thinking differently at the beginning clear, Heidegger introduced the distinction between the central question and the basic question . The central question describes the question of beings as beings and the being of beings , which had led to various answers in metaphysics and ontology since Plato and Aristotle, while Heidegger claimed that his formulation of the basic question was aimed at being as such . His aim was not to define “ being ”, but to investigate how such determinations had come about in the history of philosophy.

The jump

This new way of thinking - with all reference to it - cannot simply be compiled or derived from the old one, because it precisely refrains from all determinations of being. In order to illustrate this radically different character, Heidegger spoke of the leap into a different way of thinking. Heidegger set out to prepare for this leap in the articles on philosophy (From the event ) . This work, written 1936–1938 and not published during Heidegger's lifetime, is considered to be his second major work. The "contributions" are among Heidegger's private writings and are worded extremely cryptically , which is why Heidegger recommended that you familiarize yourself with the lectures of the 1930s.

The leap is the transition from the first to the other beginning and thus a penetration into thinking about the history of being . In the context of "contributions" are the writings reflections (1938-1939, GA 66) The history of being (1938-1940, GA 69) About the beginning (1941, GA 70) The event (1941-1942, GA 71) and The Bridges of the Beginning (1944, GA 72).

Another metaphor for the transition from traditional metaphysics to thinking based on the history of being is Heidegger's talk of the end of metaphysics or the end of philosophy and the beginning of thinking , as expressed in Heidegger's lecture "The end of philosophy and the task of thinking" ( GA 14) takes place. According to Heidegger, in order to enable this way of thinking, the history of metaphysics must first be concretely traced and interpreted using the works of its main thinkers. Only in this way does the history of being become tangible.

History of philosophy as history of being

Heidegger understood the history of being to be the historical relationship between man and being. History is not the causally related context of events, but its determining moment is the truth of being . However, this expression does not denote a truth about being. This would mean that there is only one truth, and Heidegger rejected this idea. Rather, Heidegger used this phrase to describe his newly acquired ontological concept of truth. The term “truth of being” refers to the way in which being, as concealing and revealing , shows itself to man. According to Heidegger, this is a historical process of concealment and uncovering that humans cannot dispose of.

A world is happening

Event thinking and history of being

So if being shows itself in different ways in the course of history , then, according to Heidegger, there must be intersections between two such epochs . What happens at these intersection and transition points, he called an event . If the course of the different ages is to be traced, in which metaphysics gave different determinations of being, then no metaphysical, ontological or psychological principle may be imposed on this interpretation itself . According to cryptic thinking, he argues, there is no absolute and ultimate reason that could explain and insure the transitions. All that can therefore be said about such historical upheavals in the worldview is that they occur .

The history of being does not mean the history of being (because this has no history), but the history of revelations and concealments, through which a world as a whole of meaning occurs at an epoch and from where it is then determined what is essential and what is immaterial, what is and what is not . History as the history of being is not a process that is regulated by a central power: only the "that" - that is the history of being - can be said.

In this context, Heidegger also speaks of Being , as the way to being the person sends to . Heidegger's talk of the event , of the fate of being and of being deprived of being, has often brought him the charge of fatalism through its interpretation as inevitable fate . However, for Heidegger, the fate of being is not an ontic (occurring in the world) fate that rules over people, but rather a being and world fate, according to which the average behavior of people will run in certain paths. Correspondingly, this only expresses "that man does not make history as an autonomous subject , but that he [...] is always" made "by history himself in the sense that he is involved in a traditional event about the he cannot simply dispose, but that dispenses him in a certain way. "

Heidegger certainly does not assume that everything that happens to people in detail is due to this fate. For him, the fate of being and the event are not ontic (i.e. inner-worldly) powers that commanded people. Since being is not a being, it cannot be understood genealogically or causally . Heidegger coined the term event in order to indicate the transition between epochs in the history of being without resorting to ideological terms such as idealism or materialism . If one, he explains this thought, were to try, for example, to use these world views to think the historical relationship between man and truth, then there would be a permanent and indissoluble back-reference between the two: the question of how a new idealistic horizon of understanding is possible would arise refer to the changed material conditions. For a change in material conditions, however, a better understanding of natural processes is a prerequisite, etc.

Philosophy brings being to language

For the interpretation of the history of being, philosophy plays a decisive role in Heidegger's eyes, because it is the place where the throwing off of being comes to the fore , as it is grasped by it in thought. The great philosophers put the worldview of their age into words and philosophical systems. According to Heidegger, however, this should not be misunderstood as if philosophy, with its theoretical-metaphysical drafts, produced history: “ Plato did not show the real in the light of ideas since Plato . The thinker has only corresponded to what was assigned to him. ”Since, according to his view, what is - being - is most clearly expressed in the philosophical drafts , Heidegger used the traditional philosophical writings to trace the history of being. The works of the great thinkers also mark the different epochs of the history of being.

Epochs of the history of being

Heidegger identified different epochs in the history of being. He cites the etymology of the (Greek) word epochê : “to hold on to”. Being adheres to itself in its encouragement to people, which means that on the one hand truth occurs, but at the same time it also hides the fact of this revealing.

Pre-Socratics, Plato and Aristotle