Edith Stein

Edith Stein , religious name Teresia Benedicta a Cruce OCD , or Teresia Benedicta vom Kreuz (born October 12, 1891 in Breslau ; † August 9, 1942 in Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp ), was a German philosopher and women's rights activist of Jewish origin. Edith Stein was baptized into the Catholic Church in 1922 and a Discalced Carmelite in 1933 . During the Nazi era , she became a victim of the Holocaust “as a Jew and a Christian” . She is venerated in the Catholic Church as a saint and martyr of the Church. In parts of the Protestant Church she is considered a witness of faith. Pope John Paul II. Said Teresa Benedicta of the Cross on 1 May 1987. blessed and on 11 October 1998 holy . Your Roman Catholic and Evangelical Memorial Day is August 9th. She is considered to be a bridge builder between Christians and Jews.

Life

Childhood, education and philosophical work

Edith Stein was born the youngest of eleven children into a Jewish Orthodox family. Four of the siblings had died before Edith was born. Her father, the merchant Siegfried Stein, died when Edith was about a year old. The mother Auguste Stein, née Courant, continued the timber trade and enabled all children to get a solid education.

After nine years at school, the talented pupil left the ten-year Lyceum in Breslau prematurely in 1906 and helped her eldest sister Else Gordon (1874–1954) in Hamburg for almost a year , who had two children. The young Edith Stein developed a critical relationship to the religious tradition of her parents' home and at times saw herself as an atheist . Back in Breslau, the mother financed private tuition for a short time, so that Edith was admitted to the 11th grade of the grammar school in 1908 after an examination without having completed the 10th grade, where she passed a very good Abitur in 1911 .

At the University of Wroclaw , she then began a teacher training course and studied psychology , philosophy, history and German . Even then, as she wrote in retrospect, she wanted to “serve humanity”. She later studied at the University of Göttingen and Freiburg im Breisgau , most recently again in Breslau. After her state examination and doctoral thesis in 1916 on the problem of empathy , she was the scientific assistant to her doctoral supervisor, the philosopher Edmund Husserl, in Freiburg until 1918 . Although she received her doctorate with honors, she was not admitted to the habilitation . At the University of Göttingen in 1919 she unsuccessfully presented her habilitation thesis Psychical Causality ; In Breslau and Freiburg im Breisgau she applied in vain with the philosophical treatise Potency and Act . All four attempts to be admitted to the habilitation failed because of the fact that she was a woman. Edith Stein revised and finished the script in the Nazi era in 1936 under the title Finite and Eternal Being ; it could only be published after the end of the war in 1950. The writing is a plan of the ontology . In it, Edith Stein dealt with the thinking of Thomas Aquinas , Husserl and Heidegger .

Conversion and work as a teacher

The turning point in Edith Stein's life was the reading of the autobiography of St. Teresa of Ávila . On January 1, 1922 Edith Stein was in Bad Bergzabern by baptism into the Roman Catholic Church added. At Easter 1923 Edith Stein moved to the Palatinate , where she took on a position as a teacher at the schools of the Dominican Sisters of St. Magdalena in Speyer through the mediation of her spiritual guide Joseph Schwind , Cathedral Chapter .

Between 1927 and 1933 she had intensive contact with the Archabbey of Beuron ; fifteen stays are proven. The Beuronese Abbot Raphael Walzer she held for years by her plan from, in the Carmel enter, and asked them to continue to act strengthened and the public. Therefore, Edith Stein moved to the German Institute for Scientific Pedagogy in Münster , a Catholic institution, where she particularly enjoyed visiting the St. Ludgeri Church . In Münster she dealt with St. Thomas Aquinas . During this time she met the philosopher Peter Wust . Edith Stein gave lectures on the question of women and on the problems of recent girls' education.

Beginning of persecution and entry into Carmel

After the seizure of power in January 1933, the increasingly frequent riots by the National Socialists against the Jews culminated on April 1, 1933 with the call for a “ Jewish boycott ” and the pogrom mood it created . In the middle of April Edith Stein wrote a letter to the then Pope Pius XI. , with the request to publicly protest against the persecution of the Jews :

“... Everything that has happened, and is still happening every day, comes from a government that calls itself 'Christian'. For weeks, not only the Jews but also thousands of faithful Catholics in Germany - and I think all over the world - have been waiting and hoping that the Church of Christ will raise your voice to stop this abuse of the name of Christ. (...) All of us who are loyal children of the Church and who look at the situation in Germany with open eyes, fear the worst for the reputation of the Church if the silence lasts longer. "

Edith Stein did not receive a direct answer from the Vatican, but the Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII ) wrote to Archabbot Walzer that the letter had been dutifully submitted to the Pope. Edith Stein's hopes for a public statement from the Vatican were disappointed. Negotiations on the Reich Concordat had begun only a few days earlier, and although Hitler later continually broke it, Hitler's action against the Church in Germany could also be effectively restricted to a certain extent.

Under pressure from the Nazi regime , Edith Stein finally gave up her position in Münster at the end of April 1933 in order to protect the institute from damage that would have been to be expected if a native Jewish woman had been employed again. She did not receive a dedicated teaching ban or a letter of resignation.

On October 14, 1933 for the First Vespers of the high feast of their patron saint Teresa of Avila, Edith Stein entered with 42 years as a postulant in the Carmel Our Lady of Peace in Cologne and took the garment half a year later the religious name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross to. Two years later, in 1936, Edith's older sister Rosa Stein (1883–1942) was also baptized. Rosa Stein later lived as a guest and tertiary with her sister in the Dutch Carmel in Echt and looked after the gate.

Relocation to Echt and Murder

Edith Stein's Jewish origins became officially known in Cologne in April 1938, probably through an indiscretion by her prioress. After the pogrom night of November 9, 1938, she decided to move to a monastery outside of Germany and finally moved to the Karmel in Echt , the Netherlands , where she was accepted on New Year's Eve 1938. Her sister Rosa was able to take her to live with her in July 1939. With the German occupation of the Netherlands in the spring of 1940, the threat there caught up again. Edith Stein and her sister had to follow the request of the occupation authorities in December 1941 that all non-Dutch “non-Aryans” should register for “voluntary emigration”, as they had been registered with the police in Maastricht since October 1941 . The measure served the persecutors to capture the Jewish emigrants living in the country. Shortly thereafter, Edith Stein applied to the authorities to remove the two women from the emigrant lists and to allow them to stay in the monastery. In this way they wanted to prevent being forcibly sent by the Germans. At the same time, through private acquaintances, they tried to obtain an entry and residence permit for Switzerland in order to be able to flee to the Swiss Carmel Le Pâquier , but this did not succeed in time despite attempts to mediate by Hilde Vérène Borsinger .

At the beginning of July 1942, the mass deportations of Jews from the Netherlands began, who, according to official reports, were allegedly brought to "labor camps". On July 11, the Dutch churches protested against these measures in a joint telegram to the Reich Commissioner for the Netherlands , Arthur Seyß-Inquart . Seyß-Inquart reacted with the surprising assurance that Jews of all Christian denominations baptized before 1941 would be exempted from deportation if the churches did not make their protest public. Unimpressed by this offer, the Reformed State Church (as the largest Christian denomination) and the Catholic bishops of the Netherlands published their protest telegram on Sunday , July 26th, 1942. The Catholic Archbishop of Utrecht , Johannes de Jong , sent one across the country on the same Sunday Read out a pastoral letter dated July 20, which denounced the actions of the Germans against Jews. In response to this, 244 former Jews who had converted to Catholicism , including Rosa and Edith Stein, were arrested by the Gestapo on August 2, 1942 .

The two sisters were first taken to the Amersfoort police camp and then to the Westerbork transit camp , where they arrived on August 4, 1942. From here they were deported by the Reichsbahn to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp on August 7, 1942 , where they were probably murdered in the gas chamber on August 9, 1942 . One last sign of Edith Stein's life comes from the Schifferstadt train station , where the transport stopped briefly on August 7 at around 1 p.m.

Interpretation of their fate

In her will of June 9, 1939, Edith Stein wrote:

“Already now I accept with joy the death that God intended for me in perfect submission to His most holy will. I ask the Lord that He would like to accept my life and death for his honor and glory, for all concerns of the most sacred hearts of Jesus and Mary and the Holy Church, in particular for the maintenance, sanctification and perfection of our holy order, namely the Cologne and genuine Carmel, as atonement for the unbelief of the Jewish people and so that the Lord may be received by his own and his kingdom come in glory, for the salvation of Germany and the peace of the world, finally for my relatives, living and dead and all that God has given me has given: That none of them get lost. "

Even after her conversion, Edith Stein felt that she belonged to the Jewish people. The baptism and the Order Entry eleven years later called voltages produced in the family, especially with her mother, her conversion to Catholicism as apostasy understand.

Edith Stein saw it as her destiny to accept the sufferings of her people in her heart in order to offer them to God as atonement: “I keep thinking of Queen Esther , who was taken from her people precisely because of that, in order for the people before the To stand king. I am a very poor and impotent little Esther, but the King who chose me is infinitely great and merciful, ”she wrote in the autumn of 1938.

How much Edith Stein felt connected to her origins could be shown by a statement she has handed down: “Come on, we're going for our people!” She is said to have said this when the Gestapo picked her and her sister from Carmel in real life . The statement, however, is not guaranteed and does not appear in the earliest biography of Edith Stein or in the files of the beatification process.

Afterlife

Adoration

Edith Stein was beatified on May 1, 1987 by Pope John Paul II in Cologne . The canonization took place in Rome on October 11, 1998. In 1999 Edith Stein - together with the hll. Birgitta and Katharina von Siena - declared patroness of Europe . Her commemoration day on August 9th is therefore a festival in the regional calendars of European countries . August 9th is also her day of remembrance in the Evangelical Name Calendar of the Evangelical Church in Germany . The relic of the choir mantle of the saints is in the Landricuskirche to Real, a relic from the robe of St.. Teresia Benedicta of the Cross is in the Speyer Cathedral, another in the altar table of the parish church Telfs-Schlichtling .

Commemoration

In Wachenheim the Catholic Church is under the patronage of St. Dedicated to Edith Stein. In Hamburg-Allermöhe there is the Edith-Stein-Kirche and an Edith-Stein-Platz. The Edith-Stein-Karmel in Tübingen, which was built in 1978 and has since been closed, was also subordinate to Edith Stein's patronage. A chapel consecrated to Edith Stein stands in Cologne- Bilderstöckchen . In 2016, the Catholic Church on the Riedberg was consecrated to Edith Stein in Frankfurt am Main . In Wuppertal-Vohwinkel, Lettow-Vorbeck-Strasse was renamed Edith-Stein-Strasse in September 2011.

Various streets, schools , buildings, clinics and public facilities in German and Austrian cities are named after Edith Stein. In the Dutch city of Hengelo , the college of education bears the name Hogeschool Edith Stein .

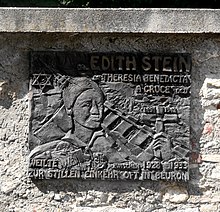

Memorial plaques were placed on the house in Dürener Strasse in Cologne, where the Carmel had stood at the time, on an inner wall of the Katharinen Chapel of the Speyer Cathedral and at the Kybfelsen inn in Freiburg- Günterstal , where she stopped in 1916, 1929 and 1931/32 , appropriate. There is also a memorial plaque on her former home in downtown Göttingen. An Edith Stein memorial was set up in the Toni Schröer House in Lambrecht (Palatinate) . A permanent exhibition about Edith Stein is in the Dominican convent of St. Maria Magdalena shown in Speyer.

The Edith Stein Prize is awarded every two years by the Edith Stein Circle in Göttingen to personalities, groups and institutions who are socially committed across borders. It consists of a medal with the inscription "Our love for people is the measure of our love for God" and is endowed with 5,000 € .

There are stumbling blocks in Cologne Vor den Siebenburgen 6, at Dürener Strasse 89 and at Werthmannstrasse 1, in Freiburg im Breisgau at Goethestrasse 63, Riedbergstrasse 1, Zasiusstrasse 24, Dorfstrasse 4 and Spitzackerstrasse 16 in Günterstal, and in Breslau at ul Nowowiejska 38. The latter, laid on October 12, 2008, was the very first stumbling block in Poland .

Stolperstein Werthmannstrasse 1, Cologne-Lindenthal

Stolperstein Dürener Strasse 89, Cologne-Lindenthal

Stolperstein Vor den Siebenburgen 6, Cologne-Altstadt-Süd

Stolperstein ul. Nowowiejska 38, Wrocław

Representation in art

As part of the redesign of the sculpture program for the Cologne town hall tower in the 1980s, Edith Stein was honored with a figure by Paul Nagel on the fourth floor on the north side of the tower. In the church in Wachenheim an der Weinstrasse , consecrated to Edith Stein , there is a sculpture created by Leopold Hafner . The sculptor Bert Gerresheim created two depictions of Edith Stein in bronze. In 1999 the Edith Stein memorial was erected for the square in front of the seminary of the Archdiocese of Cologne . In March 2009 Edith Stein was honored in Berlin by the Ernst Freiberger Foundation with a bronze sculpture by the artist Bert Gerresheim. The bust is part of the "Street of Remembrance" in the Moabit district on the Spreebogen.

To the right of the southern choir portal at Freiburg Minster , Hans-Günther van Look , a student of Georg Meistermann , created a colored glass window (2001) showing Edith Stein in the habit of the barefoot Carmelites. The artist emphasized the tension between nature and vision by depicting the face of the saints photo-realistically, while four abstract segments of a nimbus surround the saint like a firmament. Van Look designed the portrait in grisaille technique based on a black and white passport photo from 1938.

The Cologne artist Clemens Hillebrand also depicted Edith Stein in a window in the Church of the Visitation of Mary in Wadgassen .

In the Vatican , Pope Benedict XVI blessed on October 11, 2006 a statue of the saint, which was then placed in one of the outside niches of the Vatican St. Peter's Basilica . The 5.80 m high sculpture made of white Carrara marble , which represents Edith Stein as the patroness of Europe and carries a cross and a Torah scroll , was created by the artist Paul Nagel .

A sculpture by the artist Peter Brauchle was erected in Landau (Palatinate) in November 2008 as part of the inauguration of Edith-Stein-Platz . In 2006 the Bavarian State Government decided to accept Edith Stein into the Walhalla memorial in Donaustauf. On June 25, 2009, a marble bust by the Traunstein sculptor Johann Brunner was unveiled in the Walhalla .

In the novel Group Portrait with Lady by Heinrich Boll is the figure of the nun Rachel called Haruspika , clearly inspired by Edith Stein.

Fonts (selection)

- The problem of empathy in its historical development and from a phenomenological perspective . 1917. ( Dissertation Freiburg, Philosophische, 1917, 132 pages, 105 pages).

- To the problem of empathy . Halle (Saale), 1917. (Parts II and IV from the above dissertation) New edition in Edith Stein complete edition. Volume 5, Herder, Freiburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-451-27375-9 .

- Potency and Act. Studies on a Philosophy of Being. (1931), published posthumously in 1988; NA in Edith Stein Complete Edition, Volume 10, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 3-451-27380-2 .

- Finite and Eternal Being (1937), published posthumously Freiburg: Herder, 1950; NA (including attachments) in Edith Stein Complete Edition, Volume 11/12, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 3-451-27381-0 .

- Cross Science. Study on Joannes a Cruce . (1942). Nauwelaerts, Louvain 1950 . NA in Edith Stein Complete Edition, Volume 18, Freiburg, 2nd edition. 2004, ISBN 3-451-27388-8 .

- From the life of a Jewish family and other autobiographical contributions . Nauwelaerts, Louvain 1965 . Revised and introduced by Maria Amata Neyer (= Edith Stein Complete Edition . Volume 1). Freiburg 2002, ISBN 3-451-27371-3 .

A first edition of the work appeared in 18 volumes as Edith Stein's works between 1950 and 1998 by Herder Verlag. With the completion of this edition, work began on a second edition that meets today's editorial standards, the Edith Stein Complete Edition (ESGA) in 27 volumes, also published by Herder. It was published by the Carmel Mary of Peace in Cologne, with the scientific collaboration of Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz and other scholars. The first volume was published in 2000, and in 2014 the ESGA was completed. For the ESGA, the holdings in the Edith Stein Archive in the Carmel Mary of Peace were used. The Edith Stein Archive holds around 25,000 manuscripts by Edith Stein. There is also a small museum there. The inauguration of the new Edith Stein Archives took place on February 7, 2010.

Films, documentaries

- 1982: Edith Stein: Stages of an Unusual Life - Documentation by Ulrich von Dobschütz on behalf of the SDR

- 1995: The Jewess - Edith Stein ( Siódmy pokój ) - feature film by Márta Mészáros with Maia Morgenstern

- 2003: The Truth of Edith Stein - Documentation by Marius Langer on behalf of Bayerischer Rundfunk

- 2011: Edith Stein - Documentation as part of the program Schlesien Journal

- 2018: A Rose in Winter - Biopic by Joshua Sinclair

literature

Bibliographies

- Edith Stein. A bibliography. 10. revised, ext. Ed. Library of the Episcopal Seminary St. German, Speyer 2010, OCLC 76322726 .

- Sarah Borden, Kevin Jones: 2008 Edith Stein Bibliography. Baltimore Carmel, Baltimore 2008

- Yann Moix: Mort et vie d'Edith Stein. coll. Livre de pocket, Grasset & Fasquelle, Paris 2009 (not translated into German)

Anthologies

- Edith Stein Yearbook. Published on behalf of the Teresian Carmel in Germany by the International Edith Stein Institute in Würzburg. Real publishing house, Würzburg. Volume 1: 1995; Volume 18: 2012. ISSN 0948-3063 ; Volume 19: 2013, ISBN 978-3-429-03593-8 ; Volume 20: 2014, ISBN 978-3-429-03689-8 .

- Reto Luzius Fetz , Matthias Rath , Peter Schulz (eds.): Studies on the philosophy of Edith Stein: International Edith Stein Symposium, Eichstätt 1991. (= Phenomenological research. Volume 26/27). Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau 1993, ISBN 3-495-47765-9 .

- Jakobus Kaffanke , Katharina Oost (ed.): "Like the forecourt of heaven." Edith Stein and Beuron. In: Steps. Conference reports of the Beuron Days for Spirituality and Mysticism Archabbey St. Martin Beuron. Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2003, ISBN 3-87071-110-8 .

- Elisabeth Stiefel: You were a mess. Women in resistance. Elisabeth von Thadden , Edith Stein, Corrie ten Boom , Katharina Staritz , the parsonage chain . Francke , Marburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-86827-493-6 , pp. 41-69.

Monographs

- Anna Jani: Edith Stein's path of thought from phenomenology to the philosophy of being. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2015, ISBN 978-3826056048 [1] .

- Christof Betschart: Unrepeatable seal of God. Personal individuality according to Edith Stein (= Studia Oecumenica Friburgensia. No. 58). Reinhardt, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7245-1925-6 . ( academia.edu or rero.doc ).

- Matthias Böckel: Edith Stein and Judaism. 2nd Edition. Paqué, Ramstein 1991, ISBN 3-88765-022-0 .

- Elisabeth Endres : Edith Stein. Christian philosopher and Jewish martyr. Piper, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-492-02779-2 .

- Bernhard Bumb, Joachim Feldes: In the footsteps of Edith Stein through Cologne. 2nd Edition. Edith Stein connects, Frankenthal / Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-023009-7 .

- Christian Feldmann : Edith Stein. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-499-50611-4 .

- Francisco Xavier Sancho Fermin: Letting Go - Edith Stein's Path from Philosophy to Carmelite Mysticism. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-17-019980-4 .

- Zdzislaw Florek: The mystical purification process - a way to freedom. Depth phenomenology of suffering according to Edith Stein (= origins of philosophizing. Volume 8). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-018221-8 . (Dissertation University of Munich 2002/2003)

- Peter Freienstein: Understanding meaning. The philosophy of Edith Stein. Turnshare, March 28, 2007, ISBN 978-1-903343-95-1 .

- Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz : Relentless light. Edith Stein , (= philosophy, mysticism, life. ) Grünewald, Mainz 1991, ISBN 978-1-903343-95-1 .

- Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz, Wolfdietrich von Kloeden : Edith Stein (= hero without a sword ). be.bra, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-937233-52-9 .

- Cordula Haderlein: Individual human being in freedom and responsibility. Edith Stein's educational idea. University of Bamberg Press, Bamberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-923507-46-7 .

- Waltraud Herbstrith: Edith Stein. Jew and Christian. A portrait. 4th edition. Neue Stadt, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-87996-338-X .

- Maria Adele Herrmann: Edith Stein. Your years in Speyer. Media-Maria, Illertissen 2012, ISBN 978-3-9814444-5-2 .

- Sr. M. Adele Herrmann, Sr. M. Theresia Mende: Edith Stein in memory. St. Magdalena Monastery, Speyer 1987.

- Norbert Huppertz : The letter of St. Edith Stein. From phenomenology to hermeneutics. Pais, Oberried near Freiburg im Breisgau 2010, ISBN 978-3-931992-26-2 .

- Robert MW Kempner : Edith Stein and Anne Frank . Two in a hundred thousand. The revelations about the Nazi crimes in Holland before the jury in Munich. The murder of the "non-Aryan" monks and nuns. Freiburg im Breisgau 1968, DNB 457181761 .

- Marcus Knaup: Meeting Edith Stein. Questions and answers on current ecclesiastical and social issues. Pais, Oberried near Freiburg im Breisgau 2011, ISBN 978-3-931992-31-6 .

- Daniela Köder: That none of them get lost: On the spirituality of the vicarious atonement with Edith Stein. AV Akademikerverlag, Saarbrücken 2012, ISBN 978-3-639-38774-2 .

- Cordula Koepcke: Edith Stein. One life. Echter-Verlag, Würzburg 1991, ISBN 3-429-01346-1 .

- Elisabeth Lammers: When the future was still open. Edith Stein - the decisive year in Münster. dialogverlag, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-933144-65-5 .

- Mette Lebech: The philosophy of Edith Stein. From phenomenology to metaphysics. Peter Lang, Bern 2015, ISBN 978-3-0343-1851-8 .

- Inge Moossen: The unhappy life of the 'blessed' Edith Stein - A documentary biography. Haag + Herchen, 1987, ISBN 3-89228-141-6 .

- Andreas Uwe Müller, Maria Amata Neyer: Edith Stein - the life of an unusual woman. Düsseldorf 2002.

- Teresia Renata de Spiritu Sancto (Teresia Renata Posselt): Edith Stein: Sister Teresia Benedicta a cruce, philosopher and Carmelite; an image of life gained from memories and letters. Nuremberg 1950.

- Giovanni Paolo: Canonizzazione della Beata Teresa Benedetta della Croce, Edith Stein. Piazza San Pietro, Roma 1998. OCLC 67957859 .

- Wolfgang Rieß: The way from I to the other - The philosophical foundation of a theory of the individual, community and state in Edith Stein.

- Francesco V. Tommasi: L'analogia della persona in Edith Stein. Fabrizio Serra Editore, Pisa-Roma 2012.

- Bernd Urban: Edith Stein and literature. Readings, receptions, effects. (= Origins of Philosophizing. Volume 19). W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-021499-6 .

- Katharina Westerhorstmann: Self-Realization and Pro-Existence. Being a woman at work and at work with Edith Stein. Schöningh, Paderborn 2004, ISBN 3-506-71337-X .

- Reiner Wimmer: Four Jewish philosophers: Rosa Luxemburg , Simone Weil , Edith Stein, Hannah Arendt (= Reclam library . Volume 1575). 2nd Edition. Reclam, Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-379-01575-X .

- Gabriele Ziegler: Edith Stein - Searching, vigilant and decisive. Vier-Türme-Verlag, Münsterschwarzach 2017, ISBN 978-3-89680-599-7 .

items

- Beat W. Imhof: Edith Stein's philosophical development , part 1: Life and work , (= Basel contributions to philosophy and its history , volume 10), Birkhäuser, Basel 1987, ISBN 3-7643-1933-X (dissertation University of Basel, 344 Pages).

- Anna Jani: The search for modern metaphysics. Edith Stein's Heidegger Excerpts, a Critique of the Metaphysics of Dasein. In: Edith-Stein-Jahrbuch 2012. Echter Verlag, Würzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-429-03493-1 , pp. 81-109.

- Anette Klecha: Angels, locomotives and the impossibility of becoming a “Frau Professor”. A look at the world of Edith Stein (1891–1942). In: Angela Dinghaus (Ed.): Frauenwelten. Biographical-historical sketches from Lower Saxony. Hildesheim 1993, pp. 284-293.

- Wolfdietrich von Kloeden: Edith Stein. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 15, Bautz, Herzberg 1999, ISBN 3-88309-077-8 , Sp. 1318-1340.

- Rainer Marten : Edith Stein and Martin Heidegger. In: Edith Stein Yearbook. 2, 1996, pp. 347-360. (online) (PDF; 258 kB)

- Maria Amata Neyer: Edith Stein's letter to Pope Pius XI. In: Edith Stein Yearbook 2004. Echter, Würzburg 2004, pp. 11–30.

- Maria Amata Neyer: Holy Sister Teresia Benedicta a Cruce (Dr. Edith Stein) . In: Helmut Moll (ed.): Witnesses for Christ. The German martyrology of the 20th century . 7th, revised and updated edition. tape 2 . Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78012-6 , pp. 1078-1083 (edited on behalf of the German Bishops' Conference).

- Elisabeth Prégardier , Anne Mohr, with the collaboration of Roswitha Weinhold: Edith Stein and her companions: Path in death and resurrection (= witnesses of contemporary history . Volume 5 ). 2nd Edition. Annweiler 1998.

- Konrad Repgen : Hitler's "seizure of power", the Christian churches, the Jewish question and Edith Stein's petition to Pius XI. from [9] April 1933. In: Edith-Stein-Jahrbuch 2004. Echter, Würzburg 2004, pp. 31-64.

- Johannes Schaber: Phenomenology and Monasticism. Max Scheler, Martin Heidegger, Edith Stein and the Beuron Archabbey. In: Holger Zaborowski, Stephan Loos (Ed.): Life, death and decision. Studies on the intellectual history of the Weimar Republic . (= Contributions to Political Science . Volume 127). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2003, pp. 71-100.

- Katharina Westerhorstmann: "Burn in the flames of love ..." Mysticism with Edith Stein. In: A. Middelbeck-Varwick, M. Thurau (ed.): Mystics of the modern age and the present. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2009, pp. 109-139.

Web links

- Literature by and about Edith Stein in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Edith Stein in the German Digital Library

- Edith Stein Society Germany eV

- Biography, literature and sources on Edith Stein from the Institute for Women's Biography Research

- Sarah Borden and others: Materials on Edith Stein, including an extensive bibliography (as of 2008).

- Estate at the University Library of Cologne with online digital copies.

- Edith Stein Archive of the Carmel Mary of Peace

- Central database of the names of the Holocaust victims Edith Stein

- Documents on academia.edu

- Thomas Szanto, Dermot Moran: Edith Stein. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Commemoration for Edith Stein in Auschwitz-Birkenau, patroness of Europe and women's rights activist . Interview with Stefan Dartmann, SJ , Renovabis , on the occasion of Cardinal Meisner's sermon on the 70th anniversary of Edith Stein's death in the former Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp; Domradio , September 8, 2012.

- ↑ John Paul II : Address at the beatification, published among other things as “Come, we go for our people” . Address at the beatification of Edith Stein in Cologne, in: Christliche Innerlichkeit 22 / 3–5 (1987) ( transcript online ); also z. B. in: L'osservatore romano 127/106 (May 4, 1987), pp. 4-5; Ders .: Edith Stein: Jewish woman, philosopher, religious woman, martyr, in: Ordenkorrespondenz 28/3 (1987), pp. 260–266. Remembrance day is August 9, cf. Schott , The festivals and memorial days during the year (online)

- ^ Commemoration for Edith Stein in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Patroness of Europe and women's rights activist . Interview with Stefan Dartmann, SJ, on the occasion of Cardinal Meisner's sermon on the 70th anniversary of Edith Stein's death in the former Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Domradio, September 8, 2012.

- ↑ cf. Website karmel.at: Edith Stein .

- ↑ "Stein, Edith Dr. phil. Blessed, Holy Sister Teresia Benedicta a Cruce ”. In: Helga Pfoertner: memorials, memorials, places of remembrance for the victims of National Socialism in Munich 1933–1945. Live with the story. ( Memento from June 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Volume 3, Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2005, p. 81. (online)

- ↑ Reiner Wimmer: Edith Stein. In: Four Jewish women philosophers. Leipzig 1996, p. 226 f.

- ↑ Reiner Wimmer: Edith Stein. In: Four Jewish women philosophers. Leipzig 1996, p. 228.

- ^ Website of the Philosophical Faculty of the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf : Edith Stein. “Finite and Eternal” , last accessed on August 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b c The text of the letter from Edith Stein, the accompanying letter from Archabbot Raphael Walzer (Beuron), who brought the letter to Rome, and the answer from State Secretary Eugenio Cardinal Pacelli can be found in M. Amata Neyer: The Letter from Edith Steins to Pope Pius XI. In: Edith Stein-Jahrbuch 2004. ( Memento from September 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 9.2 MB), Würzburg 2004, pp. 18–22.

- ↑ Hubert Wolf: Pope and the devil. The Archives of the Vatican and the Third Reich. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57742-0 .

- ↑ see also Konrad Repgen: Hitler's "seizure of power", the Christian churches, the Jewish question and Edith Stein. Submission to Pius XI. of April 9, 1933. In: Edith Stein-Jahrbuch 2004. pp. 31-68.

- ^ M. Amata Neyer: The letter of Edith Stein to Pope Pius XI. In: Edith Stein Yearbook 2004 ( Memento from September 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 9.2 MB), Würzburg 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Felix M. Schandl: "I saw the Church grow out of my people". Edith Stein's Christian relationship to Judaism and its practical consequences. In: Teresianum 43 (1992/1), pp. 53-107; here: p. 101 f.

- ↑ Christa mother: Hilde Vérène Borsinger - My country, Switzerland, has proven to be incapable of saving a woman as great as Edith Stein. In: Waltraud Herbstrith: Edith Steins supporters. Known and unknown helpers during the Nazi dictatorship. Berlin 2010, pp. 61–64.

- ↑ Felix M. Schandl: "I saw the Church grow out of my people". Edith Stein's Christian relationship to Judaism and its practical consequences. In: Teresianum 43 (1992/1), pp. 53-107; here: p. 103 f.

- ↑ Lukas Mihr ( IBKA ): Ad maiora mala vitanda - The example of the Netherlands ( Memento of September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (online publication of November 8, 2010 at hpd , Pius XII and the Holocaust )

- ↑ Joachim Feldes: Edith Stein and Schifferstadt. 2., updated Edition. 2011, pp. 57-75.

- ^ Letter of October 31, 1938, in: ESW. IX, 121.

- ↑ According to the testimony of Marike Delsing, the eyewitness and neighbor of the Real Carmel, who accompanied the Stein siblings to the police car (Andreas Müller, Amata Neyer: Edith Stein. P. 279, note 26).

- ↑ Felix M. Schandl: "I saw the Church grow out of my people". Edith Stein's Christian relationship to Judaism and its practical consequences. In: Teresianum 43 (1992/1), pp. 53-107; here: p. 104 u. Note 151 f.

- ↑ Edith Stein in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints .

- ↑ http://www.kloster-st-magdalena-speyer.de/angebote/erinnerungsst%C3%A4tte-an-edith-stein/

- ↑ Biography of Dr. Edith Stein on stolpersteine-in-freiburg.de , accessed on June 12, 2019.

- ↑ stumbling blocks | Freiburg-Schwarzwald.de. Retrieved on August 9, 2017 (German).

- ↑ stadt-koeln.de: Sculptures on the fourth floor , accessed on January 15, 2015.

- ^ Website of the Freiburg Minster

- ↑ Website of the Church of the Visitation of Mary in Wadgassen with a window cutout , accessed on October 3, 2011.

- ↑ Heinz-Günther Schöttler: Jewish and Christian symbolism unhappily mixed. The new Edith Stein statue at St. Peter's Basilica. In: Freiburg circular. No. 2, Bamberg 2007.

- ↑ "The details that are scattered about the figure of Rahel in the text show many similarities with the life dates and circumstances of the [...] nun Edith Stein (1891–1942; Teresia Benedicta a cruce)." (Heinrich Böll: Gruppenbild mit Dame (1971). In : Ralf Schnell, Jochen Schubert (eds.): Heinrich Böll. Works. Cologne edition, volume 17, with commentary and appendix. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2005, p. 538, commentary).

- ^ Edith Stein Complete Edition , accessed on November 14, 2014.

- ^ Announcements from the Edith Stein Society. Issue 72, June 2014, p. 4.

- ↑ see online library website ( Memento from October 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ edit-stein.com

- ↑ in German, Italian, Latin and English

- ↑ further editions in Attempto-Verlag, with various ISBNs. All editions since 1995 with bibliographical notes, previous editions not. First a series of lectures at the Universities of Konstanz and Tübingen.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stein, Edith |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Teresia Benedicta a Cruce, Teresia Benedicta of the Cross |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Jewish philosopher, nun, sister of Rosa Stein and victim of the Holocaust |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 12, 1891 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wroclaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 9, 1942 |

| Place of death | Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp |