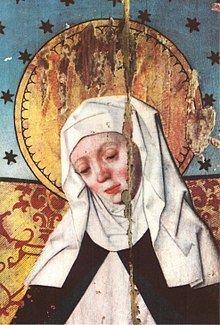

Birgitta of Sweden

Birgitta von Sweden or Birgitta Birgersdotter (* 1303 in Finsta , Sweden ; † 23 July 1373 in Rome ) was the wife of the noble Ulf Gudmarsson , court master at the court of her cousin Magnus Eriksson , advisor to his wife Blanca von Namur , mystic and founder of the Order of the Redeemer . She is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church , and the Old Catholic , Evangelical and Anglican Churches also regard her as an important witness to the faith. Your Memorial Day is the July 23 , in the calendar of the extraordinary form of the Roman rite of 8. October .

As a consultant of nobles and two popes could also work for a peace policy, as the Hundred Years' War between England and France, and in 1375 from impending schism .

Bridget of Sweden was founded in 1999 by Pope John Paul II. Together with the Church Teacher Catherine of Siena and St. Edith Stein to the patroness of Europe raised.

Life

family

Birgitta came from the nobility and one of the most powerful families in Sweden. Her father, Birger Persson, was the presiding judge in Uppland , a large landowner and a member of the royal imperial council. Her mother, Ingeborg Bengtsdotter, was related to the ruling royal family.

Early years and marriage

Birgitta was born in Finsta near Stockholm in the Uppland province in 1303 . It was her wish to enter a monastery from an early age . Birgitta is said to have experienced some visions as a child : As a seven-year-old, the Virgin Mary appeared to her and placed a golden crown on her head. The crucified Christ appeared to her for the first time at the age of eight .

Thirteen-year-old Birgitta was married to the eighteen-year-old Ademar Ulf Gudmarsson, the governor of Närke , who was the son of the knight, imperial council and presiding judge of Västergötland, Gudmar Magnusson. She moved to Ulvåsa Castle near Motala as a housewife and wife .

Birgitta and her husband Ulf lived on Ulvåsa for over twenty years. During this time Birgitta gave birth to eight children, four boys and four girls. Her son Bengt died before his twelfth birthday and another son, Gudmar, died at the age of ten. Her daughter Merete became the educator of the young Queen Margarethe I. In addition to her role as a housewife and mother, Birgitta also looked after women who were excluded from society for various reasons.

King Magnus II summoned Birgitta to the court in 1335 as chief steward of his young wife Blanca von Namur. In 1339 she and her husband Ulf went on their first pilgrimage to Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim ( Norway ), the grave of St. Olaf . After her return she left the court and two years later made a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain , where she was confronted with the confusion of the Hundred Years War . On the way home, Ulf fell ill and died in the Cistercian monastery of Alvastra in 1344 . She stayed in the monastery for another two years, where she described revelations she had experienced . She felt called to be “the bride of Christ and mouthpiece”. So she began a strictly ascetic life, but was still active at the royal court. In a revelation of Christ in 1346 she was commissioned to found a new religious community and a monastery . In his will, the king ordered her to leave the Vadstena estate on Lake Vättern to her, where she laid the foundation stone for the Vadstena monastery and wrote down the rules of the Order of the Redeemer, whose sisters are usually referred to as Birgittens or Birgittens . In the same year she sent an embassy to Pope Clement VI. who was in Avignon to persuade him to return to Rome.

Birgitta got involved in politics as an advisor at the court of the young King Magnus Eriksson and Queen Blanca in Vadstena and unabashedly criticized the lifestyle of clergy and noble dignitaries, including the royal couple. She later criticized by Rome King Magnus II. Not only so sharp, because he is a homoerotic maintained liaison with the young Swedish aristocrats Bengt Algotsson, but also because it has persisted despite papal excommunication the Holy Mass attended.

In Rome

In 1349 she left Sweden and, according to her revelations, moved to Rome, where conditions were like civil war. Just one year later, in the ecclesiastical jubilee year 1350, her daughter Catherine also came to Rome. The two women lived with some followers in a monastery-like community in a house in what is now Piazza Farnese . They founded a hospice for Swedish pilgrims and students and looked after prostitutes for whom they tried to make a fresh start. The mother house of the order as well as the church of Santa Brigida , which was built at the end of the 15th century, are still on this site today.

Birgitta made further pilgrimages from Rome, for example to Assisi in 1352 to the birthplace of St. Francis , the founder of the Franciscan Order, and in 1365 to southern Italy to Naples, where she and her son Karl Ulfsson were accepted at the court of Queen Joan I of Anjou . In 1364 she tried to get her order and its rules recognized by Emperor Charles IV and Pope Urban V in Avignon. After the Pope's return to Rome from exile in Avignon in 1367 and several encounters with him, in 1370 she obtained the approval of a women's and men's monastery according to the rules of St. Augustine in Vadstena, but not the recognition of her religious rules.

Brigitte tried again and again to influence international politics. So she set out to make peace in the Hundred Years War between England and France and tried again and again to get the popes to leave the exile in Avignon, France , and return to the Holy See in Rome, the decline of which she saw.

In 1372, at the age of 69, she went on her last pilgrimage, accompanied by her children Karl, Birger and Katharina, which took her via Cyprus to the Holy Land . She spent some time at the court of Eleanor of Aragon , Queen of Cyprus, to whom she was an adviser.

On July 23, 1373 she died in her residence in Piazza Farnese in Rome. Her daughter, also canonized Katharina, transferred her remains to Sweden in 1374 to the Vadstena monastery. On the way to Sweden the body was laid out for a few days in a small chapel in Gdansk , which was located at the site of today's Brigittenkirche .

In 1378 Pope Urban VI confirmed . finally the complete monastery for women and men in Vadstena, the order of the Redeemer and its rules.

effect

Birgitta shared her visions with her confessor . Soon she also wrote them down, as they often referred to other people. After a vision had ordered her to do so, she had it translated into Latin by the Cistercian prior Peter of Alvastra for further dissemination.

Shortly after her death, her daughter began collecting news about her life and reports of the miracles she wrought after her death . These were together with a manuscript of the Revelaciones extravagantes , their visions, in 1390 by relatives with the request for canonization of Pope Boniface IX. passed, the Birgitta them on October 7, 1391 sacred talks .

Together with Katharina von Siena and Edith Stein she is the patroness of Europe , raised by Pope John Paul II on October 1st, 1999.

In today's Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden there is a Societas Sanctae Birgittae , an association for clerics and lay people , which stands in the Birgittine spirituality and tradition.

For Birgitta's 700th birthday in 2003, more than 110,000 people made a pilgrimage to Finsta and especially Vadstena , where a new Birgitta Museum was opened. Today the community has 8,000 inhabitants and is called "Rome of the North".

Since October 2002 there has been a monastery of the international Birgitta sisters in Bremen in the Schnoor district .

In Germany, a Birgittinnen convent of the old order lived in the Bavarian Altomünster Monastery until January 2017 .

The visions of St. Birgitta in the fine arts

The visions she described had a great influence on the piety and the way in which biblical scenes were presented in the visual arts . During her pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1372, Birgitta experienced the birth of Jesus as if in a dream : the virgin took her shoes off her feet, put her coat next to her and took the veil off her head, so that her golden hair spread over her shoulders. After the birth she knelt in front of the newborn child, which lay naked on the floor; from it emanated rays that were brighter than the sun. While the Virgin Mary was mostly depicted in the Christmas pictures as a woman in childbirth with Jesus as a baby, after this vision became known, the artists began to portray Mary kneeling with loosened hair and without shoes, like the naked child lying in front of her on holy ground worships; the divine child no longer rests in diapers in the puerperium, nor in a crib with straw. It is also noticeable that the usual details of a Christmas picture, such as the manger with ox and donkey and the announcement to the shepherds, are only treated casually or pushed into the background.

The first artist known by name to have realized this new type of representation is Niccolò di Tommaso with the oil painting St. Birgitta and the vision of the birth of Jesus (Rome, 1373-1375, Pinacoteca Vaticana ). He was followed on this side of the Alps by an Upper Rhine master (around 1420, Kunstmuseum Basel ), master Francke (1424, Hamburger Kunsthalle ) and, in the following years , with slight modifications, in particular Robert Campin , Rogier van der Weyden , Martin Schongauer , Hans Memling , Albrecht Dürer , Mathis Gothart Nithart called Grünewald and Hans Baldung Grien. The Bethlehem vision was then once again put into the picture, particularly true to the text, by the Constance painter Rudolf Stahel (1522, Rosgarten Museum Constance ).

Birgitta's figure also appears in pictorial representations of the nine good heroines , she is a representative of Christianity in this iconographic series.

Promises and prayers

There are known prayers (the "15 Os" because they begin in Latin with the invocations O Jesus , O Rex , or O Domine Jesu Christe ), which occasionally refer to St. Birgitta, although the authorship is disputed. Eamon Duffy argues that these prayers probably originated in the north of England. These prayers later circulated with various additional promises. These promises would come true if the prayers were said with 15 our Fathers and Hail Mary for a year . In 1954, the Holy See expressly stated in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis that these promises were made later and did not relate to St. Birgitta could be traced back, and urged the local bishops not to allow their further dissemination (e.g. through printed works).

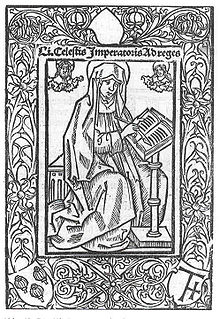

Works

The visions of St. Birgitta were first published in Latin in Venice between 1475 and 1480. The first surviving German print of the Revelationes was published by Lucas Brandis in Lübeck in 1478 . Then they appeared with woodcuts in the same year in Nuremberg and in 1492 in Lübeck with Bartholomäus Ghotan and in 1496 there in the poppy head printer of Hans van Ghetelen . In 1502 her puch of the heavenly revelations of saint wittiben was published in Nuremberg by the kingdom of Sweden in German. The state of the Church around the year made her records incredibly timely. These were intensified by the Immaculate dispute that was ruling around this time . Above all, the Revelaciones extravagantes were still highly controversial after Birgitta's canonization and were subjected to a critical examination of their orthodoxy in the 15th century at both the Council of Constance and the Council of Basel .

Modern text-critical editions

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. I. Ed. by C.-G. Undhagen. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1978.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. II. Ed. by C.-G. Undhagen † and B. Bergh. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 2001.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. III. Ed. by A.-M. Jonsson. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1998.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. IV. Ed. by H. Aili. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1992.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. V. Ed. by B. Bergh. Uppsala: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1971.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. VI. Ed. by B. Bergh. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1991.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. VII. Ed. by B. Bergh. Uppsala: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1967.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones Lib. VIII. Ed. by H. Aili. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 2002.

- Sancta Birgitta. Revelaciones extravagantes Ed. by L. Hollman. Uppsala: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1956.

- Sancta Birgitta. Opera minora Vol. I. Regula Salvatoris Ed. by. S. Eklund. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1975.

- Sancta Birgitta. Opera minora Vol. II. Sermo angelicus Ed. by. S. Eklund. Uppsala: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1972.

- Sancta Birgitta. Opera minora Vol. III. Quattuor oraciones Ed. by. S. Eklund. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities. 1991.

Monographic works

- H. Aili, J. Svanberg: Imagines Sanctae Birgittae. The Earliest Illuminated Manuscripts and Panel Paintings Related to the Revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden. Stockholm: The Royal Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. 2003.

Swedish coins and medals for the 700th anniversary of her birth (2003)

- Commemorative coin worth 2000 crowns , 900 gold, 13 gr, 26 mm (6000 pieces); Medalist: Ernst Nordin

- Commemorative coin with 200 crowns, 925 silver, 27.03 gr, 36 mm (60,000 pieces); Medalist: Ernst Nordin

- Commemorative medal , 56 mm. Finishes: gold (20 pieces), silver (500 pieces), bronze (400 pieces). Medalist: Ernst Nordin

literature

The works of Birgitta

- The visions of St. Birgitta of Sweden , edited by Elmar zur Bonsen and Cornelia Glees, Augsburg 1989, ISBN 3-629-00543-8 .

- Heavenly revelations , transmitted by Helmhart Kanus-Credé, Allendorf an der Eder

- Additional revelations. Revelationes extravagantes (German) , transferred from Helmhart Kanus-Credé, Allendorf an der Eder 2003. ISBN 3-921755-75-1 .

- Prayers to our Lord Jesus Christ in his passion: revealed to Saint Brigitta of Sweden in the Church of Saint Paul in Rome . Hauteville 1985

- Duffy, Eamon (1992). The stripping of the altars: Traditional religion in England, c.1400 - c.1580 . New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05342-5 .

Literature about Birgitta

- Barbara Günther-Haug: Birgitta of Sweden: the great seer of the 14th century . Mühlacker 2002, ISBN 3-7987-0359-0 .

- Knud Carl Ansgar Krogh-Tonning: The holy Brigitta of Sweden (Collection of illustrated Heiligenleben V), Kempten 1907

- Lars O. Lagerqvist: Sverige och des regenter under 1000 år . Norrtälje 1976, ISBN 91-0-041538-3 , p. 97 f.

- Günther Schiwy: mystic and visionary of the late Middle Ages; a biography . Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50487-6 .

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller : Magnus versus Birgitta: the fight of St. Birgitta of Sweden against King Magnus Eriksson . Hamburg 2003

- Jörg-Peter Findeisen : Birgitta: God's messenger in medieval Europe . Lahn Verlag, Limburg 2003, ISBN 3-7867-8509-0 .

- Ferdinand Holböck: God's Northern Lights: St. Birgitta of Sweden and her revelations . Christiana publishing house, Stein am Rhein / Switzerland

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Birgitta of Sweden. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 599-600.

- Lars Bergquist: Saint Birgitta in the mirror of her revelations . German by Helga Zahn. Kunstverlag Josef Fink 2011, ISBN 978-3-89870-670-4 .

Movie

- Rainer Wilder : Europe's beacon. Documentation, 60 min. Germany, Sweden, Italy, 2012. ISBN 978-3-9278-2519-2

Web links

- Literature by and about Birgitta von Schweden in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Birgitta von Schweden in the German Digital Library

- Birgitta of Sweden. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Birgitta of Sweden in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Saint Birgitta - pioneering patroness of Europe, a contribution by the church historian Rudolf Grulich

- private page The heavenly revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden

- private page Life and Revelations of St. Brigitta, after the translation by Ludwig Clarus (1888)

- Saint Birgitta of Sweden is one of the central motifs on the cover of the second LP Heretics (2014) by the American rock band Dream The Electric Sleep .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rudolph Genée: Danzig buildings in drawings by Julius Greth and J. Gottheil , Danzig 1864 (p. 14, 25, XII).

- ↑ Anette Creutzburg: The holy Birgitta of Sweden. Pictorial representations and theological controversies in the run-up to their canonization (1373-1391) , Verlag Ludwig, Kiel 2011, ISBN 978-3-86935-022-6 as well as Fabian Wolf: The birth of Christ as an event image: interrelationships between pictorial tradition and the vision of St. Birgitta von Schweden , in: Dominic Eric Delarue / Johann Schulz / Laura Sabez (eds.): The picture as an event: On the legibility of late medieval art with Hans-Georg Gadamer (Heidelberger Forschungen / 38), Heidelberg 2012, pp. 209–233.

- ↑ Duffy, p. 249.

-

↑ Acta Apostolicae Sedis, XLVI (1954), 64 : In aliquibus locis divulgatum est opusculum quoddam, cui titulus "SECRETUM FELICITATIS - Quindecim orationes a Domino S. Birgittae in ecclesia S. Pauli, Romae, revelatae", Niceae ad Varum (et al ), variis linguis editum.

Cum vero in eodem libello asseratur S. Birgittae quasdam promissiones a Deo fuisse factas, de quarum origine supernaturali nullo modo constat, caveant Ordinarii locorum ne licentiam concedant edendi vel denuo impremendi opuscula vel scripta quae praedictas promissiones continent.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Birgitta of Sweden |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Brigitta; Birgersdotter, Birgitta |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Foundress of the Order of the Redeemer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1303 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Finsta , Sweden |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 23, 1373 |

| Place of death | Rome |