Martin Heidegger and National Socialism

The relationship of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger to National Socialism (also: The Heidegger case ) can be proven from the beginning of the 1930s and was already the subject of international criticism outside of the scientific disciplines in mid-1933.

In research, there is agreement that Heidegger was enthusiastic about what he called the “National Socialist Revolution” in the “ Third Reich ”. In 1930 he began to read the Völkischer Beobachter . In 1932 he elected the NSDAP . After the seizure of power by the Nazis he wanted to participate in the transformation of society, especially through the introduction of the leadership principle at the universities . On April 21, 1933 he was elected rector of the University of Freiburg by his colleagues and on May 1, 1933 he joined the NSDAP, which celebrated his accession in public and to which he belonged until the end of the Nazi regime.

Despite all of Heidegger's commitments to National Socialism, his behavior was ambivalent. As rector, he tried in several cases to alleviate the fate of Jewish university members as far as possible. On the other hand, he denounced a Jewish and a non-Jewish colleague. In political speeches, many of which were given to students, he paid homage to Adolf Hitler, who at the time had almost messianic features for him . On the occasion of the rally of the National Socialist Teachers 'Union (NSLB) on November 11, 1933 in Leipzig, he gave one of the constituent speeches on the German professors' commitment to Adolf Hitler in front of thousands of listeners . On December 1, 1933, Heidegger also joined the NSLB. In 1934 he resigned from his post as rector prematurely, but continued to stand up for Hitler and National Socialism, in particular with the declaration of the German scientists behind Adolf Hitler published in the Völkischer Beobachter and through his membership in the committee for legal philosophy founded by Hans Frank , in which he worked until at least 1936. Heidegger's "disenchantment" with regard to the National Socialists found the first contemporary documented response in 1938 - from the exiled Bruno Altmann . Despite the stated disillusionment, Heidegger continued to give lectures and write writings that became relevant in the controversy after 1945. Some of these texts belong to the inventory which, in accordance with his will, was only gradually published as an inheritance in the complete edition .

After the Second World War , Heidegger was banned from teaching until he retired in 1951. He decided to posthumously publish the few statements he gave after the settlement process during the Nazi era.

Heidegger research today is increasingly focused on the question of whether and to what extent the National Socialist ideology can also be demonstrated in his philosophical thoughts. Since the beginning of the publication of the Black Booklet in 2014, the aspect of anti-Semitism has been discussed. The thesis of participation in Nazi crimes was discussed internationally in 2017 and 2018 in the debate on Martin Heidegger and fake news .

Posture before 1933

Relationship to Weimar Democracy

Heidegger's call for "new people" and leaders

In the year in which the First World War began, Heidegger finally opened up to “factual life” as the “philosophical starting point” when his teacher Edmund Husserl turned away from the “transcendental I” in favor of a less abstract and more experienced “historical I”. With this rejection of the transcendental aspect of phenomenology and the turn to mere existence, Heidegger also took positions that corresponded to the “ Ideas of 1914 ” and, for example, in Max Scheler's Genius des War (1915), with the definition of war as the possibility Express revelation of true substance.

Still in the service of the civil administration of the German Army and responsible for post and weather observation, Heidegger wrote a letter to his wife on October 6, 1918 complaining about the "complete aimlessness u. Holiness and alienation of values “that dominated the life of the state. In the looming defeat of the war, his dissatisfaction with those politically and militarily responsible resulted in a demand that combined the new with the original and the spirit:

“Only new people who have an original relationship with the spirit and the like can help. carry his demands within himself and I myself recognize more and more urgently the need for leaders - only the individual is creative (also in leadership) - the masses never. "

These comments in personal letters are among the earliest testimonies to be criticized in the “Heidegger Debate”. Heidegger stamped “the masses who paid for their megalomania with their blood as uncreative” (Anton Fischer). Regarding the concept of leaders, it is said that he did not think of political, but of “spiritual” leaders ( Holger Zaborowski ). Because the Führer idea was very widespread even before the NSDAP was founded (1920) - not only in political contexts, but also among poets and philosophers such as Stefan George , Georg Simmel , Hermann von Keyserling or Hans Blüher , one of the central ideologues of the youth movement whose charismatic “Führer” idea contributed to the boom of this idea among Heidegger and others.

Holistic concept for the renewal of the university

Heidegger also saw the university in crisis. As early as 1918 he stated in a letter to his lover Elisabeth Blochmann: “This simple and calm line of spiritual being u. Life has been lost in our universities - anyone who has 'seen' this is not surprised at the inner helplessness of the academic youth, but also sees in programmatic reform proposals and the like. Theories about the 'nature of the university' just the same feeble confusion. Spiritual life can only be exemplified u. The idea of a renewal of the university based on the example of the Platonic Academy and the medieval monasteries moved Heidegger continuously until the rectorate (see below). He was concerned with restoring the connection between theory and practice, which requires a personal relationship between teachers and students at the university: “Relationships in life, however, are only renewed in the return to the real origins of the mind; as historical phenomena, they require calm and the security of genetic consolidation, in other words: the inner truthfulness of valuable, self-building life. ”For Heidegger, philosophy must determine academic life holistically in all subjects, in the sense of the“ habitus of a personal existence ”. This description of his ideal, which is still influenced by the philosophy of life , also includes an "exemplary example" by the teachers.

At a birthday party for Edmund Husserl in 1920 he found a partner in Karl Jaspers who was also close to the topic and who had similar thoughts. However, Jaspers reacted cautiously to the "combat community" sought after during a joint one-week retreat in the Jaspers von Heidegger house. “Both criticize the modern 'massing'; Jaspers does this from a liberal, Heidegger from a nationalist perspective. "

Doxography on the “fighting community” with Jaspers

Friendship with the disciples

According to his student Günther Anders , Heidegger had already represented a “ mentality not very far removed from Blubo ” in the 1920s . Heidegger was also friends with the brothers Ernst and Friedrich Georg Jünger in the 1920s , was influenced by their socio-political ideas and in turn influenced them both philosophically. Like her, he was close to the movement of the “ Conservative Revolution ”, which rejected the Weimar Republic and wanted to replace it with an elitist and authoritarian “ Third Reich ”. With many other literary representatives of the war youth generation , he shared a decided rejection of bourgeois morality, which was regarded as hypocritical after the First World War, in favor of a warlike realism . What Heidegger originally had in common with National Socialism was the turning away from liberal , socialist and restorative - conservative currents in the Weimar Republic . However, he was not politically active, but strove for an ordinariate .

Politicization during the ordinariate

With the beginning of the extraordinary position in Marburg in 1923, a self-portrayal emerged that continued with the Freiburg full-time professorship in 1928 and stood in contrast to the conventions of academic scholars: Heidegger dresses like the Bündische Jugend and presents himself as an unadapted, elitist outsider, the wants to radically renew the university philosophically and pedagogically. His student Max Müller testifies for this winter semester:

“None of his students thought of politics back then. No political word was used in the exercises. [...] Heidegger and his students had a completely different style than the other professors. They went on excursions, hikes on foot and on skis together. There, of course, the relationship to nationality , to nature, but also to the youth movement was expressed. The word 'völkisch' was very close to him. He wasn't thinking of just any party. His esteem for the people was also linked to certain scientific prejudices, e.g. B. with the absolute rejection of sociology and psychology as urban- decadent ways of thinking. [...] A romanticism held him to ' blood and soil ', and technicality drew him to the 'new society'! "

But the political aspect of this popular style emerged when Heidegger, in his lecture “Introduction to Philosophy” from 1928/1929, saw the philosopher at the university called “to take on something like a leadership in the respective whole of the historical coexistence”.

And the lecture the following year on "Basic Concepts of Metaphysics", in which he refers to Nietzsche's radical questioning of Christianity, was seen as a document of the growing politicization of Heidegger's philosophy. In this time of crisis in the Weimar Republic, he stated that boredom was the basic mood and now called on people not to counteract it, but to let them vote through, knowing that this demand did not fit into the “programmatism” of the time. In the political trivialities and party bickering of liberal democracy , “in all the organizing, programming and trying things out”, he saw only “a general, satisfied feeling of being safe”. The radicalism that scornfully ridicules “today's normal people and honest man”, who “becomes anxious and sometimes black in front of their eyes”, demand the great turn-around:

“We must first call again for someone who can terrify our existence. For what about our existence when such an event as the world war has passed us by essentially without a trace? "

Approach to the NSDAP

From worshiping Hitler to calling for a dictatorship

On October 2, 1930, Heidegger wrote to his wife: “I just had a Völkisch observer with me . Father was very interested in it. The Leipzig trial seems to revert to the famous accusers. There is a big Hitler party here on Saturday; There were huge posters everywhere: 'We're attacking!' ”In a Christmas letter from 1931, he suggested to his brother Fritz that he should come to terms with Hitler's Mein Kampf , and for Christmas he gave him a copy of it. He assessed Hitler as the person who alone could be trusted to save the West. For him he is the charismatic leader, distinguished by an infallible “political instinct”. Heidegger recommended books such as Hans Grimms Volk ohne Raum and Werner Beumelburgs Deutschland in Ketten , a work from 1931 that wanted to free the German nation, which was depressed by the Versailles Peace Treaty, from its “chains” and called on them to become the guardians of their fate .

At the turn of 1931/32, Heidegger's former doctoral student Hermann Mörchen from Marburg paid him a visit to the hut in Todtnauberg, where Elfride was also present. As Mörchen noted in his diary, his former teacher has now taken the political positions of his wife:

“Of course we didn't speak of philosophy, but above all of National Socialism. The once liberal supporter of Gertrud Bäumer has become a National Socialist, and her husband is following her! I would not have thought it, and yet it is not really surprising. He does not understand much about politics, and so his disgust for all mediocre half-measures leads him to hope for something from the party, which promises to do something decisive and thus above all to effectively counter communism. Democratic idealism and Brüning's conscientiousness could, once it got that far, achieve nothing. So today a dictatorship that does not shrink from Boxheimer means must be approved. Only through such a dictatorship can the worse communist one, which annihilates all individual personality structures and thus all culture in the occidental sense, be avoided. He hardly deals with individual political issues. Those who live up here have different standards for all of this. "

The remote hut existence described in this way in the context of the turn to National Socialism as its explanatory model is controversial in research. Heidegger poses as a lonely philosopher who, far from the “humanitarian plains”, “sits enthroned on solitary peaks of spirituality”. S. Vietta rates the local situation in Todtnauberg as a bad condition "to follow and understand political events." On the other hand, the objection is that "Heidegger is once again stylized as a thinker alien to the world and politics", "who is blind in something, that he was unable to overlook, stumbled into it. ”In addition to these interpretations for the beginning of the affinity to National Socialist ideology, researchers and others are debating. a. the possibility of an instrumentally sensible motive in which National Socialism appeared to him to be the only means against the “cultural destruction by communism”, and the possibility of an already existing character that “expressed itself in his texts”. The discussion as to whether and to what extent there was a direct connection between Heidegger's philosophical work and his political thinking is also broad. (More under reception)

Heidegger's steps towards the election of Adolf Hitler

At the beginning of 1932 Heidegger criticized his brother Brüning's efforts to pursue Hindenburg's re-election and recommended that Hitler be elected as Reich President. He dismissed objections to this and the vulgarity of the Nazis as "concerns of frightened citizens". In June 1932, for example, he wrote to his wife about the "bumbling and unclear stuff of the Nazis".

“The 'level' in Völkisch. Observer]. is z. Z. again under all criticism - if the movement did not otherwise have its mission, one could grasp the horror. […] The clearer it becomes to me where I belong and what else I can do from my work and the like. this time also has to demand from the innermost self [...] the more lonely it becomes [...]. "

In the context of the Weimar Republic, like many of his contemporaries, he regarded the NSDAP as a lesser evil, a group with a narrowly defined task:

"The Nazis demand so much effort from you, it is still better than this creeping poisoning to which we have been exposed in the last decades under the catchphrase 'culture' and 'spirit'."

In the Reichstag election of July 31, 1932 , Heidegger, according to his son Hermann, elected the Völkisch Württemberg farmers and wine growers' association . When Hitler gave his election speech in Freiburg two days earlier, his father did not come with us. In October 1932 there was once again a critical attitude towards the untrained and inexperienced National Socialists:

“Of course the Nat.soz. fail everywhere. ... But the assumption is confirmed that the Naz. no trained u. experienced people have. I find the article Zehrers u. his criticism of Naz.soz. very good."

In the next Reichstag election on November 6, 1932 (there was no parliamentary majority in July), Heidegger nevertheless elected the NSDAP. He still refused to join the party. In December 1932, Rudolf Bultmann wrote to inquire that he had heard of rumors "that you are now also politically active and have become a member of the National Socialist Party." In view of the "splendid National Socialist students" he himself had placed great hopes in the movement, yes are now the impressions "depressing". Heidegger replied that this was just a "latrine rumor" and that he would "never" be a member of the NSDAP. And he explains: “On the other hand, I am very positive about many things, despite the great inhibitions that I have for example. B. compared to the 'spirit' and the 'level' in 'cultural' things. "

On June 22, 1932, the writer Lion Feuchtwanger wrote to Ernst Simon (philosopher) : “Heidegger is the opening credits of the Nat.-Soz. u. is with his seminar the party long with skin u. Prescribed hair. "

On January 30, 1933, the day Hitler was appointed Chancellor, Heidegger gave a negative lecture on the writer Erwin Guido Kolbenheyer, whom Hitler admired . He did not sign the appeal “Die deutsche Geisteswelt für Liste 1” (NSDAP), which appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter on March 4, 1933 , the day before the next Reichstag election (two Freiburg professors were among the signatories). But at the end of the same month he wrote to Elisabeth Blochmann: “For me, the current events - precisely because a lot remains dark and unresolved - an unusual collecting power. It increases the will and to work the security in the service of a large order and to help build a popularly founded world. ”The“ path of the first revolution ”, which he saw in“ Hitler's work ”, should only be“ a second and prepare deeper "revolution. He expresses his disappointment over the first weeks of the National Socialist seizure of power in a further letter dated April 12: “Nevertheless, many people went there and back. are busy here, you can't see what has to be done with the universities. ”Although a lot is being done, this kind of activism does not lead to the right steps. It is true that the new state's mistrust of the universities, "where there is a lot of reaction right now," is right. However, this should not lead to “the opposite mistake of only handing over the tasks to party comrades”.

Relationship with Jews (1916–1933)

Heidegger's statements about Jews and his personal relationship with them are controversial in their evaluation today. For the period from 1916 to 1933, primarily documents that he wrote himself, but also testimonies from others, are used. In the private letters to his future wife Elfride, but also in less personal letters, there are formulations that, according to the opinion of the majority of researchers, correspond to anti-Semitic stereotypes. For example, he writes about his assistant: “Brock - I don't think he can work in the seminary. It's strange how the Jew is missing something. ”Personal relationships with Jewish colleagues like Ernst Cassirer and Hannah Arendt were also characterized by respect. The reports that Heidegger prepared at the end of 1932 and in 1933 on the Jewish philosophers Siegfried Marck and Richard Hönigswald are debated in the context of self-interest and the question of whether his attitude towards Jews had changed after 1933. Edmund Husserl saw in him in May 1932 the transition to “harsh anti-Semitism.” Whether Heidegger was anti-Semite, conditionally or not at all, is represented by the whole spectrum of conceivable opinions in research.

Relevant quotes in letters (1916–1932)

Letters to Elfride

Before 1933, Heidegger made several statements about Jews in private letters. In October 1916, in the context of the “ Jewish census ”, he wrote to his future wife Elfride: “The Judaization of our culture a . Universities, however, are terrifying and I think the German race should still muster as much inner strength as possible to get up. However, the capital ! ”In 1920 he wrote to her:

“There is a lot of talk here about the fact that so many cattle are now being bought from the villages by the Jews [...]. The farmers up here are also gradually becoming impudent u. everything is inundated with Jews and Slide. "

Shortly afterwards, he panned a work on Hölderlin with the expression "... sometimes one would like to become a spiritual anti-Semite". In the echo of research, these letter quotations appear partly only as a result of his anti-modernism and “anti-urbanism”, but partly as evidence of his anti-Semitism: through the formulation of “Jews and smugglers”, as a stereotype of the “haggling Jew”, “the one in every anti-Semitism represents one of the most familiar figures in Judaism ”. In 1924 he asked himself how his colleague Paul Jacobsthal managed to pay his assistant more than he, Heidegger, earned as an associate professor and answered: "The Jews!"

In 1928, now in Marburg, Heidegger wrote to his wife about his students: “Of course: the best are - Jews.” Insofar as Elfride is considered an anti-Semite, the interpretation of the sentence is open. Occasionally, however, there were expressions of appreciation towards Jews to her, possibly “in order to exert a moderating influence on his wife.” So he had written to her in 1920 that he “learned a lot while studying from Bergson” and on June 9, 1932: “Baeumler ordered the 'Jüdische Rundschau' for me, which provides excellent information and advice. Has level ". Against this again, on June 20 of the same year: “What you said about the Judenblatt u. Writing the tick [?] was already my thought. One cannot be suspicious enough here. "

The letter to Schwoerer and the word "Verjudung" (1929)

As in the private letter to Elfride (see above), Heidegger now also used the term "Judgment" in a more official letter. In order to receive a scholarship for Eduard Baumgarten and to win him over as an assistant, on October 2, 1929 he sent a request to the deputy president of the Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft , the independent administrative lawyer Victor Schwoerer:

"What I was only able to indicate indirectly in my testimony, I can say more clearly here: It is about nothing less than the indispensable reflection that we are faced with the choice of bringing real down-to-earth forces and educators back to our German intellectual life, or the growing ones Judgment in the further u. in the narrower sense finally to be delivered. "

Ulrich Sieg , who published the letter in 1989, comments: "Even if Heidegger may not have been an anti-Semite in the biological sense, there should no longer be any doubt about his anti-Semitic sentiments." Tom Rockmore also judges that Heidegger's anti-Semitism is clear and even with that Antibiologism compatible. The student of Heidegger and controversial conservative historian Ernst Nolte , on the other hand, claims that Schwoerer as “anti-anti-Semites” could have used “the word 'Judgment'” “without causing offense.” Schwoerer were completely alien to anti-Semitic prejudices. “Judgment” is set in opposition to being down-to-earth. Otto Pöggeler emphasizes that Nietzsche's wild attacks against Judaism as the root of all uprooting and moralization would "certainly" be leading if Heidegger at that time demanded "real down-to-earth forces and educators" against "the growing Judaism". Heidegger had also applied for a scholarship for Karl Löwith at Schwoerer a year earlier .

Doxography on the word "Verjudung" in writing to Schwoerer

Response to accusations of anti-Semitism (1932)

In 1932, Heidegger responded in the last letter to Hannah Arendt (until 1950) to her question about the rumors of his anti-Semitism that were heard among Jewish students. In it, he calls the allegations "defamation", but on the other hand he admits to anti-Semitism "in university issues":

“The rumors that worry you are calumnies that fit perfectly with the other experiences I've had in recent years. The fact that I cannot exclude Jews from the seminar invitations well may result from the fact that in the last 4 semesters I had no seminar invitation at all. The fact that I shouldn't greet Jews is such bad gossip that I will certainly remember it in future. To clarify how I relate to Jews, simply the following facts: I am on leave this winter semester and therefore announced in good time in the summer that I would like to be left alone and not accept work and the like. Anyone who comes anyway and urgently needs to and can do a doctorate is a Jew. Anyone who can come to me monthly to report on a major ongoing work (neither dissertation nor habilitation project) is a Jew again. Anyone who sent me an extensive paper for urgent review a few weeks ago is a Jew. The two scholarship holders of the Notgemeinschaft, which I got through in the last 3 semesters, are Jews. Anyone who receives a scholarship to Rome through me is a Jew. Whoever wants to call that 'enraged anti-Semitism' may do it. Incidentally, I am just as anti-Semite on university issues today as I was 10 years ago and in Marburg, where I even found the support of Jacobsthal and Friedländer for this anti-Semitism . This has nothing to do with personal relationships with Jews (e.g. Husserl, Misch , Cassirer and others). And it can certainly not affect the relationship with you. "

Whether “Heidegger has thus declared himself to be an 'anti-Semite' to Hannah Arendt” or rather denies that he is, is undecided in research. The self-accusation is "cynical" and "nebulous", says Bernd Grün. How the anti-Semitism mentioned by Heidegger is supposed to have found the "support" of two colleagues of Jewish origin has not yet been clarified either. It is also controversial whether the letter contains hostility, resentment (Zaborowski) or pride (Obermayer) towards Jewish students. Apart from the fact that Heidegger describes here as a favor, which is part of the duties of his office, it is clear in his defense that he divides the Germans into Jews and non-Jews.

The two reports on Siegfried Marck

Siegfried Marck , who was part of the critical Wroclaw School of Neo-Kantianism around Richard Hönigswald, was to be appointed as his successor at the Silesian Friedrich Wilhelms University there in 1929. The socialist of Jewish descent viewed the existential philosophy, especially that of Heidegger, in an opposing way, and referred to it as the "fashion philosophy of European fascism". In Marck's words, the emotional moments were "raised to cult, enveloped in romantic fog and sealed off from progress, reason and science." For the appointment to Breslau, however, two reports were requested from Heidegger, who was previously attacked by Marck in this way. On November 7, 1929 he wrote in the first report: “I saw Mr. Marck here in Rickert's seminar shortly before the war. His 'weighty' demeanor by no means encouraged me to get to know him. "

In the report, Heidegger states that he only knew of Marck's publication The Dialectic in Contemporary Philosophy , in which Heidegger's philosophy is criticized, which, according to him, is one of those undertakings that represent “no serious scientific needs and tasks”. The book lacks "just like the similar kind of the Frankfurt private lecturer Fritz Heinemann any substance and all heavy weights".

The first report concludes: “There is no need for me to go into the book here, because it does not belong at all to the class of publications that can be considered as proof of qualification for a professorship. In general, I am amazed that Mr M. is up for debate on this question of composition. ”In the second report, Heidegger recommended the psychologists Kurt Lewin , because of their“ scientific quality ”, and Adhémar Gelb , who had a“ certain philosophical instinct ”and was“ humane very excellent fellow ”. Commenting on the first publication of the expert report in 1989, N. Kapferer judges that Marck “was a philosopher from the point of view of his entire approach that Heidegger could not accept” and continues: “In addition, there is certainly also the fact that Marck had dared to criticize him . Will one be allowed to assume an anti-Semitic motive here? Kurt Lewin and Adhemar Gelb, recommended by Heidegger, both came from Jewish parents. ”Despite the negative reports from Heidegger, Siegfried Marck was appointed Hönigswald's successor at the University of Breslau in March 1930.

Relationship with Ernst Cassirer (1923–1932)

In December 1923, during a "discussion that the author was able to maintain occasionally in a lecture in the Hamburg local chapter of the Kant Society (...) with C.", the first of three encounters between Heidegger and his older and ubiquitous colleague Ernst Cassirer took place . In that first conversation, Heidegger said in Sein und Zeit , “there was a consensus in the requirement of an existential analytics”. In 1926 he was accepted into the appointment committee for the chair of philosophy at the University of Marburg , Heidegger wrote to Jaspers: “One part of the faculty has the only principle: no Jews and, if possible, a German national; the other ( Jaensch and his appendix): only mediocre and nothing dangerous. ”Three months later, a criticism of it reads: The philosopher of Jewish origin Ernst Cassirer was“ cut off in the introduction to the list as an honor (...) And what the worst was - factually, the gentlemen had no interest at all - it was only a matter of strengthening the German national and ethnic party in the faculty ”. According to Zaborowski, “these letters do not point to nationalist or anti-Semitic thinking by Heidegger at all - on the contrary”.

The second meeting with Cassirer, which followed three years later, took place in the spring of 1929 during the Davos disputation and is often considered evidence of the assumed contradiction between Heidegger and Jewish philosophy. Ernst Cassirer's wife Toni, who sat next to him for two weeks in the evenings during the Davos university days while Cassirer was ill, reported in retrospect in 1948 that she had been expressly prepared for “Heidegger's strange appearance (...):“ his rejection of any social convention was known to us; likewise his hostility to the neo-Kantians , especially to Hermann Cohen . His tendency towards anti-Semitism was not alien to us either. ”According to Toni Cassirer, Heidegger was willing to“ dust the work of the Jewish founder of Neo-Kantianism and destroy Ernst if possible ”. However: “I started such a naive conversation as if I knew nothing of his philosophical or personal antipathies.” Soon she saw herself with pleasure, “this hard dough like a bread roll that has been dipped in warm milk soften. "Finally:" When Ernst got up from the sickbed, it was a difficult situation for Heidegger, who now knew so much about him personally, to hold out the planned hostile attitude. "However, Heidegger had already visited the sick Cassirer at the sickbed, and whether it was has actually given a "planned hostile attitude" is otherwise unproven and questionable in view of the first respectful meeting. During the third meeting, which took place at Heidegger's in Freiburg in 1932, he appeared to his interlocutor Cassirer to be “open-minded and very friendly”.

Doxography based on Toni Cassirer's quote

The time of the Freiburg rectorate (1933–1934)

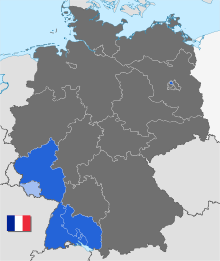

In research, the election of Heidegger as the new rector of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg on April 21, 1933 was recognized as exemplary for the National Socialist “ Gleichschaltung ” of German universities. The background of the events that led to his predecessor, the democratically minded professor of anatomy Wilhelm von Möllendorff , resigning after only six days in office, are still unclear. The focus is, among others, to debate the impact had the two decrees on the new personnel policy that the later Reich Governor in Baden and Gauleiter Robert Wagner decided on 6 April 1933 and the role of the Nazi party through intermediaries such as the philologist Wolfgang Aly it took and finally, to what extent Heidegger himself helped to take over the rectorate of the university. Heidegger began the implementation of the reorganization of the educational institutions in the sense of holistic concepts there with the establishment of the Führer principle and in Todtnauberg with the so-called science camp, in which he at least allowed a lecture on race theory.

Rector of the NS "Gleichschaltung"

Beginning of NSDAP rule and Heidegger's election

On December 17, 1932, Wilhelm von Möllendorff was elected as the new rector of the Freiburg University , and on April 15, 1933, he duly assumed his office. But after the changed balance of power as a result of the Reichstag election of March 1933 , from which the NSDAP emerged as the strongest party in Baden with 49 percent of the votes, the National Socialists demanded the resignation of the Baden government, whereupon Robert Wagner on March 9, 1933 with the SA and SS -Units in front of the Home Office and took over government. The NSDAP Gauleiter, who had already participated in the Hitler putsch and was later one of those responsible for the Wagner-Bürckel action , then, as the new ruler in Baden, had the so-called "Baden Jewish Laws" (see below) announced on April 5, 1933 without any legal basis the next day and before the law for the restoration of the civil service of April 7, 1933 came into force and provided for the removal of all Jewish scientists from university service. In addition, Wagner issued a decree calling for the election of new university senates.

The boycott of Jews begun nationwide on April 1, 1933, had been supplemented by the Freiburg Nazi campaign paper “ Der Alemanne ” with a boycott list, which had been added: “The Jewish teachers and doctors at the universities are listed in a special way,” which was in the Freiburg University led to "confusion". On April 9, Freiburg's mayor, Karl Bender, was forced to resign and was replaced the next day by the NSDAP district leader Franz Kerber . Two days later, Cologne University took the lead in the process of the self-chosen "synchronization" of the German universities, in that the rector, Godehard Josef Ebers , resigned from the office that was held by Ernst Leupold , a member of the Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten and confidante of the NSDAP, What the Nazi minister of education Bernhard Rust called a "trend-setting example" was adopted and will have justified the beginning of the resignation of the still incumbent rector of Freiburg University, Joseph Sauer , and the designated rector von Möllendorff at the rectors' conference in Wiesbaden on the following day : They hardly saw themselves in a position to prevent the synchronization in Freiburg. Von Möllendorff was already thinking of resigning.

When von Möllendorff, who was hostile to the National Socialists for his democratic convictions, became the rector of the university on April 15 according to the vote of the previous year, talks had already begun behind the scenes to end his term of office immediately in favor of a candidate whose election the new one Took power relations into account. It is undisputed that Sauer and the classical philologist Wolfgang Schadewaldt negotiated before von Möllendorff took office to propose the rector's office to Heidegger, who is a friend of Schadewaldt, although it is unclear whether Heidegger used his friend and colleague as a middleman or rather let himself be convinced by him and what role he played NSDAP and SA member Wolfgang Aly fell to it, who presented himself as a "gray eminence" in the background. A diary entry shows that Sauer hesitated because he did not trust Heidegger with the office.

The new rector was attacked in the Alemannen on the Tuesday after the Easter holidays. Under the heading “Herr von Möllendorff as rector of the university unsustainable” it said on April 18: “We cannot imagine how a sphere of trust can arise between Professor von Möllendorff and the predominantly National Socialist student body. (...) We encourage Prof. Möllendorff to take the opportunity and not stand in the way of a reorganization of the university. ”On the same day, von Möllendorff reported on the Jewish decrees in a senate meeting and announced that he would have the senate re-elected, whereupon the Rector and Senate announced their resignation on April 20. The next day the plenum met with partly new members - 13 Jewish participants had meanwhile been on leave due to the racial legislation and were replaced by non-Jewish colleagues - and on von Möllendorff's proposal, Heidegger was almost unanimously elected as the new rector.

Doxography on von Möllendorff's resignation and Heidegger's candidacy

Heidegger's resolutions on Nazi racial policy

Due to the new racist legal situation, but also due to corresponding activities in the predominantly National Socialist student body, Heidegger, as the elected rector of the Gleichschaltung of the university, had to make several decisions in this regard before taking office.

- The resolution on the Wagner decree A 7642

The decree issued on April 6, 1933 by Nazi Gauleiter Wagner to remove Jewish scientists from the Baden universities did not contain a “ front-line combatant privilege ”, according to the scholars of Jewish origin who served in World War I in Section 3 (2) of the Professional Civil Service Act (BBG) had been spared from the scheme. After a request from the University of Freiburg on April 22, 1933 regarding the priority of both laws, the new, still acting minister of education, Otto Wacker , replied on April 26 that the Wagner decree “will not be affected” by the state-wide law. Thereupon Heidegger, in his capacity as the designated rector, put the Wagner decree into force by resolution 4012 at the university against the exception regulation.

“The representative of the Reich (...) saw himself compelled to order (...) in the interest of the Jews living in Baden that all (...) members of the Jewish race are to be taken off duty with immediate effect until further notice. (...)

Robert Wagner, April 6, 1933. ”

“I ask you to ensure that the decree of April 6, 1933 (…) is fully and clearly implemented, otherwise the university runs the risk of making any advocacy for threatened colleagues futile.

(...) Heidegger, April 28, 1933. "

On the same day, in the priority dispute with the BBG, the Minister of Education and Cultural Affairs Wacker immediately revoked decree 7642 and thus some leave of absence "until final clarification".

Doxography for the Wagner decree

- On May 3, Heidegger limited the number of “non-Aryan” students to 1.5 percent in accordance with the law against overcrowding in German schools and universities . In Freiburg, however, fewer students of Jewish origin were matriculated for the summer semester of 1933, so this provisional maximum limit was not reached in any case.

- On May 4, Heidegger signed a decree by the Baden university advisor and SA member Eugen Fehrle , which granted discounts to students "who have been in the SA, SS, or military associations in the last few years in the fight for the national survey": On the other hand, discounts may no longer be given to Jewish or Marxist students. ”However, at the University of Freiburg students of Jewish descent have been granted fee waivers.

- On the prohibition of the poster "Against the un-German spirit" ("Judenplakat")

Heidegger stated in writing in 1945 - almost verbatim in the Spiegel interview in 1966 - he had, as rector, prevented it from being hung:

“My first official act on the second day of my rectorate was the prohibition of hanging up the 'Jewish poster' in any rooms belonging to the university. The poster was already up at all German universities. (...) About eight days later there was a telephone call from the SA University Office to the top SA leadership from an SA group leader Dr. Baumann. He asked for the poster for Jews to be displayed. If I refuse, I would have to expect my dismissal, if not the closure of the university. I continued to refuse. "

This statement is also controversial, as there is no written evidence for Heidegger's version.

Doxography for the poster "Against the un-German spirit"

- Inaction in the Neo-Friburgia case

On May 16, the house of the Jewish student association “Neo-Friburgia”, which had to disband on April 20, was besieged without permission from the NS student union. But Heidegger did nothing. After the house was looted and destroyed by the mob on June 28, 1933, the rectorate declined to investigate.

Heidegger's entry into the NSDAP

On May 1st, National Labor Day , Heidegger and his wife Elfride joined the NSDAP in a public ceremony. According to Martin to Fritz Heidegger , this happened “not only out of inner conviction”, but “also out of the awareness that this is the only way to purify and clarify the whole movement. Even if you do not make up your mind to do so at the moment, I would advise you to prepare yourself internally for entry and in no way pay attention to what is going on around you in terms of low and less pleasant things. "

The time of joining is considered well considered: he initially wanted to secure his rector's office and maintain room for maneuver vis-à-vis colleagues who were now surprised by the move. In his autobiography, Jaspers described his reaction when Heidegger joined the NSDAP: “'How should a person as uneducated as Hitler rule Germany?' - 'Education is completely indifferent', he replied, 'just look at his wonderful hands!' [...] I was at a loss. Heidegger had not told me anything about his National Socialist inclinations before 1933. “According to Gerhard Ritter, however, Heidegger had been known as a National Socialist long before 1933.

Doxography on Heidegger's entry into the NSDAP

To the "Gleichschaltung" and to the national struggle

- Adolf Lampe rated as "politically unreliable"

In May 1933 Heidegger prevented the extension of the representation of a chair that his opponent, the later resistance fighter of the "Freiburg circles" Adolf Lampe , had taken over, who was thus provisionally placed under § 4 of the Professional Civil Service Act, which was the "political unreliability" in the National Socialist Meaning.

- Circular letter on conformity to Hitler

On May 20, at the request of Karl Lothar Wolf , the National Socialist rector of the University of Kiel, Heidegger signed a circular telegram to Hitler requesting that the reception of the board of the Association of German Universities be postponed until the "Gleichschaltung “The leadership of the university association would also be Nazi-minded.

Doxography for the telegram to Hitler

Speeches and lectures

- First lecture as rector

On May 4th Heidegger gave his first lecture since his election as rector: “The basic question of philosophy and the basic events of our history. The intellectual-political mandate as a decision on the basic question ":

“The German people as a whole come to themselves, i. H. finds his guidance. In this leadership the people who have come to themselves create their state. The people, shaping themselves into the state, creating permanence and steadiness, grows up to become a nation. Such a people win their spiritual mission among the people and create their own history. This event reaches far into the difficult future of a dark future. And with this development, the academic youth is already on the move and they stand by their calling. And that means: She lives from the will to find the discipline and education that makes her mature and strong to the spiritual-political leadership that is to be assigned to her from the people for the state in the world of the peoples. All essential leadership lives from the power of a great, basically hidden determination. And this is first and foremost the spiritual and popular mission that the fate of a nation has reserved. The knowledge of this mission must be awakened and rooted in the heart and will of the people and their individuals. "

- Matriculation speech

On May 6th, the new rector gave his first speech on the occasion of the enrollment of the students. The matriculation means the "transfer into the fighting and educational community of those for whom the spiritual mission of the German people is the first and last". And inferred from this, with Heidegger's earliest documented mention of the word “ Volksgemeinschaft ”: “Admission to the highest school of intellectual-political education obliges you to be extremely strict and tough against yourself in all internal and external things, obliges you to be exemplary (... ) in the midst of (...) the national community. "

- The philosophical glorification of the death of Schlageter

On May 26th, Heidegger gave his first public speech at the commemoration ceremony for the tenth anniversary of the death of Albert Leo Schlageter , a former student of the University of Freiburg who had carried out bombings against the French occupation of the Ruhr as a Freikorpsler in 1923 . The “young German hero” Schlageter basically realized the existential ideal of being and time, according to Heidegger, when he accepted the “worst and greatest death” as his own possibility in solitude. He is said to have drawn his strength from "the mountains of his homeland" (the Black Forest and "Alemannic Land"). So Heidegger tried for the first time, the day before the rectorate ceremony, in front of a large public, a political application of his philosophy.

Taking office and inaugural speech

The solemn assumption of office, at the center of which was Heidegger's inaugural speech, took place on May 27, 1933 and was prepared in detail by the rector-designate himself. To this end, Heidegger asked Freiburg's NS mayor Kerber to expand the university's orchestra “to give this year's celebration an appropriate expression”. As early as May 23, Heidegger had communicated in writing that after the inaugural speech, the Horst -Wessel song should be sung, with the right hand raised at the repetition stanza and followed by the call "Sieg Heil". As a result, a certain aversion spread among the professors, which is why Heidegger announced that raising his hand “does not mean that he is a member of the NSDAP”, but that he belongs to the “national uprising”. Eventually it was agreed that the right hand would only be raised on the fourth stanza. “The leadership role of the rector and the deans” was then prescribed “by details of the pageant. For the first time, the deans should step one step in front of the respective faculties ”.

The day before Heidegger took office, W. Aly, the oldest NSDAP member of the professorships, informed him by letter that the "broadcast of your speech on radio tomorrow, which was requested by numerous colleagues and supported by the local NSDAP district leadership" had been "rejected by the Reich Commissioner", what he regrets. It is unclear what reasons prompted Wagner to reject this. However, B. Martin concludes that the letter proves that Heidegger as rector “was also considered by the party to be the ideal man for this post”, even if one seemed to be reluctant to really let him have his say.

Inaugural address: "The self-assertion of the German university"

In the speech, Heidegger mentioned neither National Socialism nor the party, nor the name Hitler, but gave a draft for the reorganization of the university in line with the Führer principle. Due to the diverse interpretations of the speech, the following topics are listed that were partly already commented on in earlier reactions or that are mostly highlighted in the debate today.

- The extended leader principle: self-assertion

Heidegger begins his inaugural address by explaining a leadership principle that has been expanded by the fate of the people: “Taking over the rectorate is the obligation to lead this high school spiritually. (..) But this being comes seriously to clarity, rank and power if the leaders themselves are led first and foremost at all times - led by the relentlessness of that spiritual mandate that forces the fate of the German people into the stamp of its history. "

The guided leaders - this idea underlies the speech and its title of self-assertion, since it is the “German university” that should discipline those “leaders”: “The self-assertion of the German university is the original, common will to their being. We consider the German university to be the high school which, out of science and through science, takes the leaders and guardians of the fate of the German people into education and discipline. "

- The questioning and the anti-Christian and technology-critical discourse

Heidegger explains that asking questions is the beginning of science and thus also of Greek philosophy, and that asking questions is still ongoing. But the “Christian-theological interpretation of the world, as well as the later mathematical-technical thinking of the modern age” have moved away from this beginning of mere questioning. Heidegger quotes Nietzsche's saying that God is dead and explains the questioning of the modus operandi of the possibility in such “abandonment of man” to “unlock” the essentials of all things and to overcome the isolation of the academic disciplines: “The questioning (...) becomes itself the highest form of knowledge. (...) We choose the knowing struggle of the questioners ", the" fighting community of teachers and students. "

- Knowledge and skill

In order to still subordinate the "superior power of fate" to knowledge, which in view of this must first develop its "highest defiance" in order to be effective, Heidegger refers to a verse by the Greek tragedian Aeschylus, from The Fettered Prometheus :

τέχνη δ᾽ ἀνάγκης ἀσθενεστέρα μακρῷ ("The craftsmanship is much weaker than the necessity")

Heidegger, on the other hand, translates: “But knowledge is far less powerful than necessity.” To this he immediately adds the following interpretation: “That means: every knowledge of things remains previously at the mercy of fate and fails before it. Precisely for this reason, knowledge must unfold its highest defiance, for which the full power of the concealment of beings only arises in order to really fail. "

- To blood and soil

"And the spiritual world of a people is not the superstructure of a culture, any more than the arsenal for usable knowledge and values, but it is the power of the deepest preservation of its earthly and blood-like forces as the power of the innermost excitement and the greatest shock of its existence." The knowledge is therefore subject to the fate of the people, but can defiantly build up against it from the earthly and blood-like forces.

- The law of the essence of the German university

Heidegger continues: “From the determination of the German student body to withstand German fate in its extreme need, comes a will to the essence of the university. This will is a true will, provided that the German student body has placed itself under the law of its being through the new student law (...). "

The reference to “the new student law” introduces the section on the three obligations that arise from the freedom to give oneself the law with which Heidegger apparently reacted to the anti-Semitic Prussian student ordinance of April 12, 1933, “which are precisely these three Made services binding for all students ”and with which a requirement of the German student body , which has existed since the Weimar Republic, to oblige all students to labor service and student military sports in the SA, was realized in the form of“ military and labor service and physical exercises ”.

- The motif of the three "bonds" and the three "services"

According to his ideas of a holistic university, Heidegger then names the three “ties” that are to be made possible by three “services” and which, although he mentions neither Plato nor Politeia in this context, interpreted as a - partly perverse - analogy to the class structure in the Platonic city-state were.

- The first bond is that of the "national community" - this bond is "rooted in student existence through the" labor service "."

- “The second bond is that of the honor and destiny of the nation in the midst of other peoples. It demands a willingness to work down to the last, secured in knowledge and ability and tightened by breeding. (...) This bond encompasses and pervades the entire student life as "military service". "

- The third bond is “that of the intellectual mission of the German people.” - “A student youth who dares to get involved in manhood at an early age and expands their will about the future fate of the nation, forces themselves to serve this knowledge from the ground up. For her, the knowledge service will no longer be allowed to be the dull and quick training for an 'elegant' profession. "" These three ties (...) are of the same origin as the German being . "

- The use of the storm metaphor

The speech ends with a quote from Plato's Politeia . First of all, Plato says: “A difficult proof is still missing. - Which one? - In what way a polis deals with philosophy without going under. ”Then follows the sentence:“ Because all great things are endangered. ”- which Heidegger adapts to the metaphor of the storm that he frequently used at the time. “We want ourselves. Because the youngest and most recent force of the people, which reaches beyond this, has already decided on it. But we only fully understand the glory and grandeur of this awakening when we carry ourselves into that deep and wide prudence from which the ancient Greek wisdom spoke the word:

τὰ… μεγάλα πάντα ἐπισφαλῆ 'Everything great is in the storm'. (Plato, Politeia, 497 d, 9) "

"This idiosyncratic, basically wrong translation has brought Heidegger almost as much criticism as his philosophical consecration of the National Socialist national community in his remarks on the unity of labor, military and knowledge service."

The beginning of the Heidegger debate

With the assumption of office and the Rector's speech, initially published in excerpts, the occasion for encouragement and criticism was given, which has already been documented nationally and internationally for the months following the speech and which, with their polarized assessments and reactions, justify the so-called Heidegger debate. In Germany, the assumption of the rector's office was sometimes met with “enthusiastic accents”, while abroad “in quite a few cases with rejection and accompanied by severe criticism.” The text of the speech was initially only “reproduced in abbreviated form” by the local press, to which Rudolf Bultmann refers in his letter criticism (see below). Seven weeks after the rectorate ceremony, however, a publishing house in Wroclaw printed them in full, which provided “the apparently desired publicity at the national level”. The Völkischer Beobachter reported on it on July 20, 1933 under the heading: “The three ties”, and R. Harder, who sympathized with the National Socialists, praised the lecture as “a battle speech, a thought-provoking appeal, a determined and compelling self-determination -the-time-places. "

- One of the first critical voices was sent to Heidegger personally: in his letter of June 1933, Bultmann, a friend of his, called the lecture an adaptation to the hubris of the zeitgeist. He is not “blind” to the “positive achievements of the new empire”, but: “'We want ourselves!' you say when the newspaper reports it correctly. How blind this will seems to me! How much this volition is at any moment in danger of failing itself. How much has the turnaround created a υβρις [hubris] that is deaf to the demand for the spiritual world to fight over and over again under extreme exposure to the powers of being. "

- In Basel, the theologian F. Eymann wrote in the preface to Karl Ballmer's criticism of the speech: “As theoretical as this struggle may be, its results immediately become human reality as soon as they are taken seriously as such. They become dangerous when they deny HUMANS as a knowing being and thus the possibility of a recognizable truth. Because at the same time freedom as self-determination is abolished. "

- In Ballmer's text of July 1933, the principle of “taking the leaders into discipline” finds a first reaction: “Herr Heidegger, by taking Adolf Hitler 'into education and discipline', is performing an achievement that others modestly step back from. Herr Heidegger is therefore a special case in contemporary German history. ”Heidegger's limitation to asking questions is also attacked:“ By virtue of his philosophical leadership, Martin Heidegger, as rector of a German university, revealed in the spring of 1933: The task of science is not to provide knowledge spread. The task of science is not to know, but to ask. The spiritual bread that science has to give to the people is, as the highest and last, a question, a steadfast heroic perseverance in questioning. - Anyone who up to now has been of the unbiased opinion that science is knowledge, absolutely knowledge - (...) - will have to give up such popular opinion under the discipline of the masters of philosophy. "

- Karl Jaspers wrote in a letter on August 23, 1933 that the speech had a “credible substance” through the approach “in early Greek culture”, although something in it “seems a little forced” and some sentences “seem to have a hollow sound”.

- The neo-Kantian Jonas Cohn named the advantage that Heidegger saw the people as “spiritual and historical beings”, but regretted that the “determination” remained empty, that he did not mention the philosophy of the modern age, that he neglected research and, above all, the specialization of Students refuse.

- The politically liberal-minded philosopher Benedetto Croce spoke up from Italy. As the author of monographs on Goethe and Hegel and a pen pal of Thomas Mann, he had a close relationship with German poets and thinkers. Croce attacked Heidegger as the adept of a historicizing philosophy who lacked the humane, first in a letter, then in the magazine La Critica .

“At last I have read all of Heidegger's speech, which is stupid and servile at the same time. I am not surprised at the success that his philosophizing will have for a while: the emptiness and the general always succeed. But it does not produce anything (...) it dishonors philosophy, and that is also a damage for politics, at least for the future. "

- In January 1934 he specified: Heidegger

“Today suddenly plunges into the depths of a highly erroneous historicism, into that who denies history, for whom the course of history is conceived flatly and materialistically as an affirmation of ethnicisms and racisms, as a celebration of the deeds of the wolves and foxes, the lions and jackals, with the only and true protagonist absent: humanity. "

- In November 1933, the National Socialist rector of the University of Hamburg, Eberhard Schmidt , referred to Heideggers in his inaugural speech: "I don't dare to adopt the proud word Heidegger used to describe the rector's office as the 'spiritual leadership' of the university".

Doxography on the reactions to the inaugural address

The book burning in Freiburg

In a conversation with Spiegel in 1966, Heidegger said that he had "banned the planned book burning that was to take place in front of the university campus," for which there is no evidence. It is unclear whether the burning of indexed books planned for May 10th by the German student body in Freiburg also took place on this day. While the common researcher opinion is based on the fact that this was not the case - because, as in other places in Germany, heavy rains disrupted the project - there are contemporary witnesses who testified that there were books on the square in front of the university library that day were burned. In the presence of Freiburg's Lord Mayor Franz Kerber, the cremation act, with which the books removed from the public libraries by the “Commission for the fight against dirt and trash in literature” were destroyed, was to take place on June 17th with the participation of the city schools which, again due to the weather, was postponed to another day. On June 24th, Heidegger gave a short speech in front of the solstice fire in the university stadium. A second, “strangely small fire from the books of a ladder cart” burned on the edge, according to Käthe Vordtriede. Quote from Heidegger's fire quote:

"Fire! Tell us: You must not go blind in battle, but you must remain bright for action. / Flame! Your blaze tells us: The German revolution does not sleep, it reignites and illuminates the way for us, on which there is no turning back. / The days are falling - our courage increases. / Ignites flames! Heart burns! "

Opinions, dismissals, advocacy

The Hönigswald case

Since April 1933, NS students at the University of Munich had demanded the dismissal of the Jewish neo-Kantian Richard Hönigswald by means of the newly enacted anti-Semitic professional civil servants law, but those in charge of the faculty had refused to comply. The Bavarian Ministry of Culture then asked Heidegger for an expert report on Hönigswald. He considered applying for his successor in order (as he wrote to his also Jewish student Elisabeth Blochmann) "to get close to Hitler". On June 25, 1933, Heidegger, who had already judged Siegfried Marck from Hönigswald's Breslau school negatively (see above), also gave a devastating judgment on his colleague in Munich.

“Hönigswald comes from the school of Neo-Kantianism, which represented a philosophy that is tailored to liberalism. The essence of man was then dissolved into a free-floating consciousness in general, and this ultimately diluted into a generally logical world reason. In this way, under apparently strictly scientific philosophical justification, the gaze was diverted from the human being in his historical roots and in his popular tradition of his origins in soil and blood. This went hand in hand with the deliberate suppression of every metaphysical question, and humans were now only considered servants of an indifferent, general world culture. The writings (...) of Hönigwald grew out of this basic attitude. But there is also the fact that Hönigswald now defends the ideas of Neo-Kantianism with a particularly dangerous acumen and an idle dialectic. The main danger is that this hustle and bustle gives the impression of the utmost objectivity and strict scientificity and has already deceived and misled many young people. Even today I have to describe this man's appointment to the University of Munich as a scandal, which can only be explained by the fact that the Catholic system prefers people who are apparently ideologically indifferent, because they are harmless to their own aspirations and are 'objective-liberal' in the familiar way. I am always available to answer further questions. With excellent appreciation! Hail Hitler! Your devoted Heidegger. "

The explicit recourse to “ blood and soil ” is a sign of further political radicalization of Heidegger after the rector's speech, if not an anti-Semitic attitude, because Heidegger is the first to add the concept of blood to his linguistic images of the soil. Mainly because of this expert opinion - mostly seen as a political denunciation - the then 58-year-old Hönigswald was forced to retire on September 1, 1933, which began his odyssey in National Socialist Germany, which was continued with the revocation of the philosophical doctorate in 1938 and him after Brought the November pogrom to the Dachau concentration camp, from which he was released weeks later because of international protests. Heidegger's report ended Hönigswald's academic career forever, as he could no longer find a job in exile in the USA.

The Baumgarten case

After a rift between Heidegger and his assistant Eduard Baumgarten , who was still supported in the letter to Victor Schwoerer (see above), another letter, which was later heavily criticized, came about: Baumgarten had applied for admission to the Flieger-SA and to the Nazi lectureship , but the report that Heidegger wrote on the occasion on December 16, 1933, thwarted this project. The original of this document is lost, but Baumgarten himself, after learning about it, was able to inspect the files of the Göttingen Nazi Lecturers' Association through personal connections and write a copy there. Karl Jaspers used this on December 22, 1945 for his opinion on Heidegger in the adjustment committee and spoke of it in a letter on which the extracts from Constantin von Dietze were based, to which Heidegger referred in a letter of January 17, 1946. In it he stated that the part in which he had commented on Baumgarten's suitability in a "structure of the party" was "probably the copy of a party official report", which was made according to the "usual careless method" - which is now doubted becomes. A version that differs slightly from Baumgarten's comes from the "Baumgarten files" in the Göttingen University Archives, the so-called "copy of the second copy". This document states:

"Dr. Baumgarten attended my lectures from 1929–1931 (…) with the intention of (…) doing his habilitation. In the course of the time mentioned it turned out that he was neither scientifically nor characteristically suitable. (...) Dr. Baumgarten comes from the liberal-democratic circle of intellectuals around Max Weber in Heidelberg as a family member and in keeping with his intellectual attitude. During his stay here he was anything but a National Socialist ... After Baumgarten had failed with me, he dealt very lively with the Jew Fränkel, who had previously worked in Göttingen and is now released here. I suspect that Baumgarten took up residence in Göttingen on this way, which may explain his current relationships there. At the moment I consider his admission to the SA to be just as impossible as that of the lecturer. "

As a result, Baumgarten - he was a private lecturer in Göttingen - was dismissed because he was considered a “fellow Jew”. After an affidavit that he did not know Fraenkel and had never seen him, the discharge was reversed. Karl Jaspers, who was able to see a copy of Marianne Weber, Max Weber's widow , in 1934, was "deeply affected". For him, this moment was, as he wrote in a letter to Heidegger in 1949, "one of the most decisive experiences of my life." It was pointed out, however, that Heidegger's warning against Baumgarten, since he had only superficially adapted to the new circumstances, was 'entirely in the consequence of his revolutionaryism'. Isolated doubts expressed about the authenticity of the discrediting evaluations of the report are now considered unfounded.

The Staudinger case

In July 1933, Heidegger asked the Zurich-based physics professor Alfons Bühl , a representative of " German / Aryan physics ", unofficially and "secretly", because of rumors about the chemist Hermann Staudinger - who worked in Zurich from 1912 to 1926 - about "political unreliability" to pursue his behavior in the First World War. Bühl soon found what he was looking for when Staudinger had also applied for Swiss citizenship during his time in Zurich and was pacifist during the First World War. In addition, the German defense at the Bern embassy investigated whether Staudinger had advised opponents of the war on the manufacture of weapons-grade chemicals. This allegation was later dropped. On September 29, 1933, Heidegger reported the rumors to the Baden university clerk, Fehrle, whereupon Fehrle filed a complaint against Staudinger on the following day for “political unreliability” (§ 4 GWB). Because of this Heidegger's initiative, the Gestapo took action in the Staudinger case, as evidenced by an entry in the file. The action was given the code name "Sternheim". The historian Hugo Ott, who came across the incident in 1984, speaks of a “process of clear political denunciation by Rector Heidegger”, and the majority of researchers follow him in the judgment of the denunciation. On February 6, 1934, the Ministry of Culture asked Heidegger to comment on the material collected by the Gestapo and thus also to issue a legally relevant judgment. On February 10, Heidegger replied that studying the files gave the following to the question of whether § 4 should be applied: All reports spoke of the transfer of German chemical manufacturing processes by St. to (hostile) foreign countries. According to the Consulate General in Zurich in 1918, Staudinger never made a secret of the fact that he was in sharp contrast to the national tendency in Germany. Significantly, the later Marxist envoy Adolf Müller described Staudinger as an idealist. These facts made it necessary to apply Section 4 to restore the civil service. Since the facts about Staudinger have become widely known, the reputation of the University of Freiburg also demands action, especially since Staudinger is now posing as a 110 percent friend of the national survey. Dismissal rather than retirement is more likely to be an option.

In accordance with Heidegger's suggestion, the Baden Minister Wacker demanded Staudinger's dismissal from civil service on February 22, 1934. But now the Lord Mayor of Freiburg Kerber and the Mayor Leupold intervened for the world-famous chemist and later Nobel Prize winner, and “with regard to the position that the named person enjoys in his science abroad”, Heidegger came to the conclusion that although “in the matter can of course not change ”, but a“ foreign policy burden should be avoided if possible ”. Finally, Staudinger was forced to sign his own dismissal pro forma, which would have come into effect if there had been “renewed concerns”. Until the end of his life, Staudinger never found out who initiated the Gestapo investigation against him. From a psychiatric point of view, Ott's résumé found confirmation that only a “depth psychological interpretation” could reveal the reasons for Heidegger's denunciation initiative. However, a desire for recognition and self-importance on the part of the rector who had gained political influence were also mentioned as possible motives for this. In addition, Heidegger's son Hermann agreed with the interpretation, which is widespread in research, that his father was annoyed by "the ingratiating opportunism of his colleague". Finally, the philosophical reading is debated that Staudinger fell into Heidegger's sights because he represented a "purely technical view of science that Heidegger had fought against from the start".

The defense of Hevesy and Fraenkel

For the chemist George de Hevesy and the philologist Eduard Fraenkel , who were threatened with dismissal due to their Jewish origins, Heidegger wrote a joint letter of recommendation to the Ministry of Education on July 12, 1933, whereby he first emphasized, “in full awareness of the necessity of the indispensable execution of the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service ”and then referred to the“ unusual scientific reputation of Mr. von Hevesy in the entire academic world ”. Therefore, it would be "an unjustifiable unevenness of treatment (...) if Mr. von Hevesy could stay, but Mr. Fraenkel were given permanent leave", since his reputation abroad is no less. He could also vouch for their “impeccable behavior”, “as far as human judgment goes”. In the letter of July 19, 1933, Heidegger affirmed that Fraenkel was considered to be the “main representative of German antiquity, especially in Italy, Holland, Sweden, England and the United States” and that the university could maintain it as a “leading figure”. "Despite this second advocacy and the two declarations of honor that the Philosophical Faculty gave for him under Schadewaldt's deanery, Fraenkel was dismissed." In Fraenkel's case, Heidegger joined this initiative by Schadewaldt. George de Hevesy - possibly "for foreign policy reasons" - stayed until October 1, 1934, when he was "released from Baden's civil service at his own request" and went to Copenhagen.

Layoffs and advocacy

Most of the layoffs at Freiburg University during the Nazi era were carried out in the first two years, i.e. during Martin Heidegger's tenure. These therefore took place exclusively on the basis of the GWB (the RBG did not come into force until 1935). As rector, Heidegger also tried to help the Jewish students and colleagues affected by the racist legislation - provided he recognized their achievements - as in the above-mentioned Hevesy and Fraenkel cases. Private lecturers and assistants, on the other hand, could hardly rely on his support. He did not sit down for the historian Paul Theodor Gustav Wolf , the almost completely blind mathematician Alfred Loewy (Heidegger had studied with him from 1911 to 1913, he retired early on December 1, 1933), the pharmacologist Paul Noether and the legal scientist Andreas Bertalan Schwarz a. Rather, they too were removed from the university by Heidegger on the basis of racist legislation in the course of 1933. Soon afterwards, on April 6, 1934, Noether committed suicide.

Doxography for the discharge of Paul Theodor Gustav Wolf

- Werner Gottfried Brock, Heidegger's assistant, lost his teaching license on September 27, 1933 due to his Jewish origins. At first, the rector recommended him to the Swiss philosopher Paul Häberlin for a habilitation and then supported his studies at Cambridge University.

- Paul Oskar Kristeller helped Heidegger with letters of recommendation to find a job in Italy.

- In February 1934 Heidegger rejected measures against the Jewish geophysicist Johann Georg Königsberger, who was reported to the ministry by his colleague Wilhelm Hammer because of his Marxist past.

- Heidegger presumably campaigned for Elisabeth Blochmann in Berlin circles and at the end of October 1933 wrote a benevolent testimony for the job search in England.

- He probably also advocated Professors Siegfried Thannhauser , Jonas Cohn and Edmund Husserl at the Baden Ministry of Education, for which there is no written evidence. However, Cohn was still removed from Heidegger (on August 24, 1933), and Thannhauser was removed from the university during Heidegger's tenure (April 17, 1934), then demoted to the position of unskilled worker in Heidelberg.

The attempt at a holistic educational establishment

The “leadership constitution” of the university

About a month after taking office, on July 3, 1933, Heidegger wrote a circular to “all German universities” in which he announced that the university's chancellor would now “draw on behalf of the rector”. At Prussian universities it was difficult to imagine a relationship of subordination between the state representative and head of administration to a Führer-Rector ”, although the circular was sent with the intention“ that this model would also set an example elsewhere and that the rector in his competencies as a leader of the University should strengthen. ”On August 21, 1933, Baden's Minister of Education and Cultural Affairs, Wacker, until“ the university reform is carried out uniformly and throughout the entire Reich ”, by letter A 22296, abolished all existing parliamentary competencies of the university committees, senates and faculties in Baden, which were provisional University constitution came into force on October 1, 1933. From then on, the ministry appointed the rector and Section I, point 1 decreed: “The rector is the leader of the university”. This appointed the chancellors and deans. Wacker was the first minister to introduce the Fuehrer Constitution at a German university.

The day after Wacker's letter, the former Rector Joseph Sauer noted in his diary: “ Finis universitatum - End of universities. This fool von Heidegger, whom we elected rector, got us into that he would bring us the new spirituality of the university. What irony! ”Also in the opinion of the research, Heidegger is sometimes considered to be a“ promoter of this new leadership constitution ”, but sometimes it is only pointed out that he could not contradict when the clean-up commission determined in 1945“ that he had worked diligently ” . "The new university constitution", so the summary of H. Ott, "stood in the context of the reasoning of his thinking and acting."

Heidegger announced the resolution on August 24, 1933 - as a basis "for the internal expansion of the university in accordance with the new overall tasks of academic education." From now on, representatives of the student body, assistants and university employees could also be called to the meetings of the Senate, in which paradoxical "approaches to democratization" can be recognized, since the rule of the ordinaries was broken and "an, albeit modest, participation of the other curiae of university lecturers and students" was achieved, but the faculties had completely lost their right to self-determination. Instead of the self-assertion of the university proclaimed by Heidegger, it came to its “self-decapitation”. Just a week after Wacker's decision, the Bavarian university administration followed suit ("The Rector is the leader of the university"), whereby "the Baden model (...) must have been the model." The Prussian Education Minister Rust, in turn, orientated himself with his decree of 28. October 1933 based on the Bavarian model. With the takeover of the 13 Prussian universities, the leadership constitution was enforced at most German universities and could no longer be prevented as a model for a Reich-wide regulation.

Appointment as "Führer-Rector"

As planned, Heidegger was appointed by Wacker on October 1, 1933, "the first Führer-Rector of the University of Freiburg". He appointed his predecessor von Möllendorff as well as his confidante Schadewaldt (philosophy) and Erik Wolf (law and political science) as deans. Like the other appointees, neither were party members, although at that time Schadewaldt was still particularly involved in the National Socialist sense. The appointment of the lawyer Erik Wolf as dean - who in 1934 still published the essay The Legal Ideal of the National Socialist State, which was arrested in the Nazi racial concept - since "he was not accepted by his colleagues because of his 'Heidegger-bondage'" was one of the occasions for later Heidegger's resignation from the rectorate.