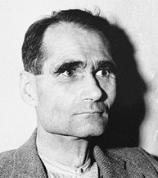

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Heß [ hɛs ] (born April 26, 1894 in Alexandria , Egypt , † August 17, 1987 in Berlin-Wilhelmstadt ) was a German politician ( NSDAP ). From 1933 Hess was Reich Minister without portfolio and from 1939 a member of the Council of Ministers for Reich Defense . In public, Hess stood out as a fanatical follower of the Führer cult . In 1933 Adolf Hitler appointed him his deputy in the party leadership. On May 10, 1941, Hess flew to Great Britain to persuade the British government to make a peace agreement. He became a prisoner of war and in 1945 was transferred to the International Military Court in Nuremberg . He was one of the 24 accused in the Nuremberg trial of the major war criminals . On October 1, 1946, Hess was found guilty on two out of four counts and sentenced to life imprisonment . In 1987, he died in Spandau Prison by suicide .

Life

Family, childhood and youth

The Hess family came from Bohemia . In the 1760s she settled in Wunsiedel in Upper Franconia , where Peter Heß established a tradition as a shoemaker. Johann Christian Heß, Rudolf Heß's grandfather, went to Trieste in 1849 and married Margaretha Bühler, the daughter of a Swiss consul , in 1861 . After the birth of Johann Fritz Hess, the father of Rudolf Hess, the family moved to Alexandria, Egypt . Johann Christian Heß founded the import company Heß & Co., which was one of the leading trading houses in the city in 1888, when Johann Fritz Heß took over the company.

Rudolf Hess was born on April 26, 1894 in Ibrahimieh , a suburb of Alexandria. His mother Klara (née Münch) also came from a Franconian merchant family.

He grew up in Alexandria in the city's German-speaking community and had little contact with the locals or the British, who administered Egypt as a colonial power . So he didn't learn English either . He only attended the German School for a short time and then, together with his brother Alfred, was taught by the German tutor Rudolf Haffner. Hess's father was very authoritarian and feared by his children.

In 1908 he was sent to an evangelical boarding school, the Otto Kühne School in Bad Godesberg near Bonn , for his high school education and never returned to Egypt. His teachers attested him an interest in astronomy, physics and mathematics. After graduating from the École Supérieure de Commerce in Neuchâtel ( Switzerland ), he began a commercial apprenticeship in Hamburg , which his father had forced him to do.

First World War

Because he knew early on that he was not well suited for the commercial profession, he used the outbreak of the First World War to ignore his father's wishes. He broke off his apprenticeship and volunteered as a war volunteer . In 1915 he fought in the infantry , including at Verdun , where he was wounded. From April to August 1915 he rose from private to lieutenant in the reserve and received the Iron Cross, Second Class .

He was later transferred to the Southeast Front, where he was wounded two more times in the summer of 1917. The last wound, a bullet below the left shoulder, took him to the hospital for several months . This wounding is controversial because it was missing on later X-rays and gave rise to doppelganger theories.

In the spring of 1918 he completed a pilot course at the Lechfeld Air Base near Augsburg and took part in the last fights near Valenciennes as a member of the Bavarian Fighter Squadron 35 . Most recently he had the rank of lieutenant .

Hess was enthusiastic about the war and showed in letters to the end that the army was in as good a condition as it was in 1914. He blamed the USPD for the war defeat . He was disappointed with the Treaty of Versailles , which he saw as the result of a “lie and deceit” by President Wilson : “One must not think about peace. […] The only thing that holds me up is the hope of the day of vengeance, no matter how far it is, ”he wrote in 1919 to his parents.

National Socialism

The early years (1919–1923)

After the war, Hess was penniless because the British had expropriated his parents' company in Alexandria. He went to Munich, ruled by the Soviet Republic , and began studying economics , history and law at the university there in February 1919 . He completed part of his studies with the professor of geopolitics , Karl Haushofer , whom he met in April 1919 through a fellow aviator and with whom he soon developed a friendship that went beyond the academic environment and that lasted his entire life.

During this time, Hess came into contact with nationalist circles when he joined the “ Iron Fist ” organization . He also became a member of the Thule Society . As a member of the Freikorps of Franz Ritter von Epp , he participated in the suppression of the Munich Soviet Republic . Here he met Captain Ernst Röhm, among others, and subsequently also joined the Artamanen . So Hess became acquainted with Heinrich Himmler .

In April 1920, Hess met the student Ilse Pröhl (1900–1995) in a Munich guesthouse . Pröhl felt drawn to Hess from the start, but Hess only slowly got involved in a relationship. He rejected her for years and did not enter into an intimate relationship.

On May 19, 1920, Hess met Adolf Hitler for the first time at a meeting of the NSDAP . According to Prohl, Hess was immediately fascinated by Hitler. On July 1, 1920, he joined the party and was given membership number 1600. Together with other like-minded people, he founded the “1. Munich NS Student Storm ”, the forerunner of the later National Socialist Student Union .

During this time, Hess developed a close bond - his “dog-like duckiness” and devotion - to Hitler, which made his own personality almost entirely disappear. In him, Hess found a replacement for the dominant father figure with whom he grew up. In November 1921 he won first prize in a competition on the subject of “How must a man be to bring Germany back up?” With an early formulation of the Führer myth. In it he described a dictator full of coldness, passion and selflessness who was clearly based on the image of Hitler and who proceeded with propaganda and brutality against Marxism , parliamentarism and the " Jews and [...] Jewish-contaminated Freemasons ". Hess was one of Dietrich Eckart , Alfred Rosenberg , Esser Hermann and Hans Frank 's inner circle of admirers who the " leader expectantly" the charisma attributed to which he was later to successfully build his rule. They also made themselves indispensable in establishing contacts. Hess, for example, introduced Hitler to Erich Ludendorff , a symbolic leader of the anti-republic right wing who was subsequently to become useful to Hitler.

Hess was not involved in the planning for the 1923 Hitler coup . On November 8, 1923 he took part in the arrest of some high-ranking hostages, including the Prime Minister Eugen Ritter von Knilling . He himself did not take part in the " Storming of the Feldherrnhalle ". After the coup failed, he fled to Austria for a few days and finally found shelter with the Haushofer family in Munich. Soon sought after in a wanted list, he surrendered to justice in Munich in April 1924. Hess feared that his case would be transferred to the Reichsgericht in Leipzig, where he would probably have been threatened with a more severe punishment than a Bavarian court, especially since Hitler had already received a mild punishment in Bavaria.

Hitler's private secretary

Hess was to 18 months imprisonment in Landsberg am Lech sentenced, where Hitler served his sentence. During the creation of Mein Kampf im Prison, Hitler had long conversations with Hess, reading to him from the manuscript, which Hess then edited and typed on a typewriter. In terms of content - apart from Haushofer's " spatial concept ", who visited him several times in prison - he had little influence, he was never a co-author or ghostwriter .

In early 1925, Hess was released from prison. When he re-entered the NSDAP after its re-establishment, he was given membership number 16, as a new party directory was created with the reorganization of the NSDAP.

In April 1925, Hess gave up his position as an assistant at Haushofer and became Hitler's private secretary. He no longer completed his studies. From now on, largely unnoticed by the public, he made appointments for Hitler, answered letters and organized all processes around Hitler. In addition, he managed Hitler's private income and built the forerunner of the later party chancellery. Hess traveled extensively on Hitler's behalf, for which he had his own aircraft since 1930. In 1932 he won second place in the sport flying competition “Around the Zugspitze ”, and in 1934 first place. Late twenties as he went to Hamburg to from Business donations for NSDAP to acquire. Only six entrepreneurs appeared, who sarcastically asked Hess' little concrete statements on economic policy and communist danger, whether "your NSDAP wants to be a kind of guard and lock-out society for large property?" Hess did not receive any donations. Hess was naive but sincere veneration and submissiveness. Hitler's unusually close relationship with Hess soon gave rise to rumors about his homosexual tendencies. Allegedly, Heß frequented Munich and Berlin homosexual circles under the code name “Black Berta”. In order to counter the talk, Hess married Ilse Pröhl in Munich on December 20, 1927 at the behest of Hitler, who was also the best man. As a result, the relationship between the couple remained little intimate. The only common child, Wolf Rüdiger , was born ten years after the marriage.

In June 1928, Hess appeared in the magazine Der SA-Mann with a justification for the Hitler salute, which had been officially introduced two years earlier; it was by no means a takeover of the Roman greeting as used by the Italian fascists , but had been customary in the NSDAP since 1921. In 1931 he got his own office in the Brown House , which was to become the nucleus of his growing staff. After Gregor Strasser, head of the Reich organization, was overthrown in December 1932, Hitler transferred the chairmanship of the newly created Central Political Commission of the NSDAP to Hess. Hess, until then hardly known to the public and personally ambitious, suddenly became the second most powerful man in the NSDAP.

Time in the Schutzstaffel

Hess joined the Schutzstaffel on November 1, 1925 with SS no. 50 and on July 20, 1929, with effect from April 1, 1925, became adjutant to the Reichsführer SS and at the same time personal SS adjutant to the "Führer" Adolf Hitler (see also section above). With SA Fuehrer's Order No. 6 of December 18, 1931, Hess was appointed SS Oberführer on the same day. This appointment was renewed with the SA leader order No. 1 "Reorganization of the SA and SS" of July 1, 1932. As such, between 1929 and October 31, 1930 and between October 31, 1930 and October 1, 1932, Heß was in charge of the SS upper section "South" (formerly known as "SS-Gau Süd"). By SA-Führerbefehl No. 10 of December 15, 1932 he was appointed SS-Gruppenführer with effect from December 5, 1932, and on July 1, 1933 he was then appointed to the SA-Führerbefehl No. 15 of July 1, 1933 SS-Obergruppenführer appointed. However, Hess resigned from the SS in September 1933, but in his capacity as "Deputy Leader" was granted the right to continue to wear the uniform of an SS-Obergruppenführer.

Reich Minister and "Deputy Leader"

Hitler's deputy in the party leadership

On April 21, 1933, Hitler appointed Hess as his deputy in the NSDAP. In this function he took part in the meetings of the cabinet from June 1933. Since December 1933, as Reich Minister without portfolio, he was also officially a member of the latter. Also in 1933 Hess received the rank of SS-Obergruppenführer . He dropped this rank in September 1933 and from then on only held the title of “Deputy Leader” (StdF). In 1933, Heß was also one of the founding members of the Academy for German Law . Further steps in his career were his admission to the Secret Cabinet Council in February 1938 and to the Council of Ministers for Defense of the Reich at the end of August 1939. On September 1, 1939, Hitler appointed him his second successor after Hermann Göring in the event of his death .

How great Hess' concrete power actually was in the time of National Socialism is controversial in scientific literature. Many authors assume that although Hess, as the Führer’s deputy, had almost absolute power over the NSDAP with his staff , he was in fact powerless. He was unable or unwilling to take his own initiatives and therefore withdrew to representative tasks such as participating in charitable events. Instead, he left the day-to-day business to his power-conscious head of staff, Martin Bormann , who was to succeed him in 1941. Hess' position in the National Socialist polycracy was on the whole rather weak: Hitler, who gave his subordinates no clearly delimited competencies in order to let them compete on the principle of "divide and rule" , had Hess the newly established staff leader of the party organization Robert at the end of 1932 Ley not reported. Thus he had no official authority over the political leaders who remained subordinate to him and who represented the actual backbone of the NSDAP. The result was protracted arguments between the two that paralyzed the party apparatus. It was not until 1941 that Ley lost the sole right to present Hitler on personnel matters in this power struggle, and thus lost a decisive advantage over Hess.

The Würzburg historian Rainer F. Schmidt , on the other hand, assumes that Hess had a strong position of power. From the law to ensure the unity of party and state of December 1933, he derived the right to control and ideologically examine all state activities, which Hitler explicitly promised him in an ad hoc order from the Führer in July 1934. The German municipal code of January 30, 1935, gave Hess the right to appoint "NSDAP representatives" in every municipality, who had to ensure that municipal offices were filled with suitable National Socialists. In September 1935, Hess was given a further decree of the Fiihrer to check the ideological suitability of all senior civil servant candidates. However, Hess soon complained about the Gauleiter , who did not give him a timely report on the candidates. These themselves remained directly subordinate to Hitler and eluded Hess' control. Overall, in Schmidt's opinion, Hess had commanded an “empire” “that was hardly inferior to that of Hermann Göring or Heinrich Himmler ”. His office grew to 172 employees by 1936 and, in the form of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the commissioner for foreign policy issues, and the party's foreign organization, which was subordinate to Hess, had its own instruments to influence foreign policy, and even had its own secret service . It was only in the years from 1936, when Hitler turned increasingly to foreign policy and preparation for war, that Hess's power increasingly waned. Since then, Hess's health has deteriorated. He mostly had the various symptoms from which he suffered treated with alternative medical methods such as homeopathy or anthroposophic medicine , for which he repeatedly campaigned.

Hess had previously been unsuccessful with his repeated admonitions to the officials of the NSDAP not to damage the party's public image by “showing off, arrogant and undisciplined behavior”. Since he kept to his appeals himself, he was soon considered a " puritan of the movement". Hess is considered one of the protagonists of the Führer cult, to which he himself adhered to the point of denying his own personality. At the mass events of the regime, he announced Hitler's appearance with genuine enthusiasm. For example, in June 1934 he declared:

"All of us National Socialism is anchored in uncritical allegiance, in devotion to the Führer, who in individual cases does not ask why, and in the silent execution of what he commands."

Such and similar statements were also rejected by many National Socialists. But they gained importance because Hess always went public before the decisive stages of the seizure of power, for example before the referendum on the merging of the offices of Reich Chancellor and Reich President with his speech on August 14, 1934, which was broadcast on all German radio stations. Here he stylized Hitler's curriculum vitae, which, starting from poor beginnings, was chosen by Providence as the savior of Germany and which "has proven that he is the embodiment of everything good in German people".

Röhm crisis

During the crisis surrounding the SA's growing claims to power , Hess was firmly on Hitler's side. As early as April 1933, he had forbidden all members of the NSDAP to interfere in the internal affairs of commercial enterprises. This is what the socialist SA had done repeatedly since it came to power. In January 1934 he wrote in an article in the National Socialist monthly magazine , which also appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter , that there was "not the slightest need for the SA to lead an independent existence" - a clear warning to Chief of Staff Ernst Röhm . After Röhm's later successor Viktor Lutze had announced that the SA chief had made derogatory comments about Hitler while drunk on February 28, 1934 (“treason”, “this ridiculous private”), Hess immediately sent him to a personal report to Hitler the Berghof . He became even clearer against the SA in the action against Miesmacher and Criticism in a radio address on June 25, 1934: The catchphrase of the “second revolution”, which Röhm had been using since the summer of 1933, only covered a “criminal game ... woe to him, the loyalty breaks in the belief that one can serve the revolution through a revolt! ”When the bloody elimination of the SA leadership began on June 30, 1934 , Hess went through the death lists with Hitler. He rivaled Max Amann to be allowed to shoot Röhm personally. The murder was committed a day later by Theodor Eicke on Hitler's orders . In September 1934, Hess publicly justified the murders at the Nazi Party Congress, which is recorded in Leni Riefenstahl's propaganda documentary Triumph des Willens . Hess addressed Hitler with the words:

“You are Germany: if you act, the nation acts, if you judge, the people judge. Our thanks are the pledge to stand by you in good and bad days, come what may! "

Persecution of the Jews

The persecution of the Jews and racial policy were a focus of Hess' legislative efforts. As early as April 6, 1933, he submitted proposals "to regulate the position of the Jews" to Julius Streicher , which anticipated the provisions of the later " Blood Protection Act " and in some cases went beyond them. On May 15, 1934, Hess was subordinated to the NSDAP's new racial policy office as the Fuehrer's deputy , which was supposed to coordinate the various racial policy officials within the National Socialist polycracy. Hess commissioned the physician Walter Groß , whose Christian-Völkisch positions he shared, with the management. In 1934, Hess issued a ban on personal contact with Jews for all party members.

Hess personally took part in the formulation of the Nuremberg Race Laws . Since then, all of the decrees and laws that determined the increasing disenfranchisement of Jews in Germany had his signature. At first it was one of Hess's tasks to propose the members of the Reich Committee for the Protection of German Blood , whom Hitler then appointed. The decisions proposed by the Reich Committee as to who should be considered a “ Jewish mongrel ” and who could be granted an exemption had to be approved by its staff. In 1935 he wrote a circular to promote the compulsory sterilizations provided for by the law for the prevention of genetically ill offspring : As a National Socialist, one should "never, especially not by religious influences, be tempted to adopt a negative attitude [...]". In the same year, in a speech in Goslar, he confessed to the conspiracy-theoretical catchphrase of Jewish Bolshevism , which was to blame for the Versailles Treaty , for hunger and unemployment, because he wanted to prepare Germany “mentally and organizationally for Bolshevization”. Hess became even clearer in his speech at the Nazi Party Congress in 1936, in which he described the Spanish Civil War as a struggle between Jews and the peoples who recognized them as their "thousand years old enemy". As a result of this struggle, he prophesied the " fall of the Jewish people ”. Since September 1939, in almost all of his speeches, Hess came back to the thesis that the deeper cause of the Second World War was to be found in Jewish machinations.

In 1937 Hess was involved in plans to impose special taxes on Jews in the German Reich. In the course of the aryanization policy , Hess spoke out against defining bindingly what exactly a "Jewish" company was. In his opinion, it is sufficient if 25% of the capital is in Jewish hands. He was also a co-signer of the law on tenancy agreements with Jews of April 30, 1939, which exempted Jews from statutory tenant protection . In July 1939, he ordered the Gestapo to observe couples whose applications for marriage had been rejected on racial grounds in order to prevent them from living together without a marriage license.

In November 1940, the Fuehrer's deputy criticized the introduction of German criminal law in the incorporated eastern regions as a mistake and called for a special criminal law and introductory law for criminal procedure law for Poland. In a note with which the draft of the “Council of Ministers Ordinance on the Administration of Criminal Justice against Poles and Jews ” was sent on April 22, 1941, it was stated that these proposals “largely took into account the wishes of the Fuehrer's deputy”, albeit in “ draconian special criminal law “Be waived from the desired flogging punishment.

Flight to Great Britain

On May 10, 1941 at around 6 p.m., Heß flew from the Messerschmitt AG works airfield in Haunstetten with a Messerschmitt Bf 110 E-1 / N ( serial number: 3869) to Scotland to fly to Dungavel Castle ( South Lanarkshire ) with Douglas Douglas Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton , whom he believed to be the leader of the British peace movement and opponent of Prime Minister Winston Churchill , to negotiate a peace. His staff member Ernst Schulte Strathaus had procured a horoscope for him that named May 10th “as a promising day for a journey in the interests of peace” . Hess had met Douglas-Hamilton in 1936 at the Olympic Games in Berlin. At around 11 p.m. he parachuted off and became a British prisoner of war. His flight was considered treason by the National Socialist government and Hess was declared insane. On May 13, Hitler spoke to the Reich and Gauleiter about Hess's flight. He tried to correct the originally conveyed image of the "crazy Hess" by explaining its motives. The whispering joke circulated among the population : “Brown budgie escaped. Submit Reich Chancellery ”.

The former secretary of the British Embassy in Berlin, Ivone Kirkpatrick , traveled to Scotland to interview Hess. In a lengthy lecture that he had prepared, the latter explained to him that Great Britain had constantly opposed Germany since the conclusion of the Entente cordiale in 1904; since it reacted only "with contempt" to all of Hitler's offers for peace, it had no choice but to go to war. In this war, Germany was materially and strategically superior, which is why it was best for Great Britain to start immediate peace negotiations: Hitler, who knew nothing about his flight, had no plans against Great Britain or its non-European possessions, he was not thinking of world domination . Rather, his sphere of interest lies in Europe and, as Hess specified in response to Kirkpatrick's inquiry, in the Soviet Union . This offer was nothing new for the British, because it corresponded exactly to the peace appeal that Hitler had publicly issued on July 19, 1940. When the British wanted to find out more about the foreign policy plans of National Socialist Germany, such as the role that the Republic of Ireland played in Hitler's plans or his plans for the United States , Hess had little to say about independent foreign policy accents that were about a mere recapitulation of Hitler's often heard views, he was unable to do so.

Hess was brought to London. Churchill ordered him to be strictly isolated but treated appropriately. On May 20, 1941, he was transferred to Maryhill Barracks and finally to Mytchett House near Aldershot in Surrey. The house was equipped with microphones and sound recorders. Three MI6 officers were entrusted with the task of evaluating the conversations from Hess - or "Z" as he was now called. To get more information out of him, the former appeasement politician John Simon met with Hess on June 9th . The two had already met in 1935 on a British state visit to Berlin. But even to Simon, Hess only repeated the same, poorly reflected ideas: he had no in-depth knowledge of Hitler's foreign policy plans, nor was he familiar with British foreign policy, which, to Simon's astonishment, he assumed had traditionally had no interests in the Continent. This conversation convinced the British that Hess had actually come on his own, with no competence to conduct peace negotiations. After reading the minutes of the conversation, Prime Minister Churchill had the impression of a "conversation with a mentally retarded child [...] which gives us something of the atmosphere in Berchtesgaden ". When Hess noticed that the British did not take him seriously and that his flight had failed, he tried to kill himself for the first time on June 15.

In research it was sometimes taken the view that Hess had undertaken his peace mission with the secret consent of Hitler, since his foreign policy program , as laid down in Mein Kampf , provided for cooperation with Great Britain against the Soviet Union. Today the majority of research is of the opinion that Hess did not undertake his flight on behalf of or with the knowledge of Hitler. In his biography of Hitler , the historian Ian Kershaw argues that Hitler was completely surprised. The German historian Rainer F. Schmidt also expressed himself in this sense .

Hitler initially had Hess' personnel arrested. One of his adjutants was held in a concentration camp until the end of the war because he had not reported Hess's plans, about which he was privy. Because Walter Schellenberg's unconfirmed reports indicate that Hess was a silent promoter and supporter of Rudolf Steiner's anthroposophy as well as various astrologers and clairvoyants , collective arrests were extended to these groups after his flight . So on June 9, 1941, there was an action against secret doctrines and so-called secret science . Hitler relieved Hess of all party and state offices and ordered him to be shot if he ever returned to Germany. However, he granted Hess's wife a pension.

Hitler did not appoint a new "Deputy Leader". Instead, Hess 'office was renamed " Party Chancellery " and Hess' chief of staff, Martin Bormann , who was simultaneously given the powers of a Reich Minister. The official statement from the German government said that Hess was the victim of hallucinations caused by old war wounds.

The British government was briefly undecided as to how to exploit Hess's flight for propaganda purposes. There were considerations to portray him as a defector who acted out of desperation about the impossibility of a final victory in order to undermine the will of the German population to go to war. This line of propaganda was also feared by Joseph Goebbels , who felt himself to be directly slapped by the "embarrassment of the Hess case [...]":

“I already read the horror reports from London by far . […] The good Hess is abused in a way that defies description. His childish naivety brings us damage that cannot be measured. "

Churchill was persuaded by Foreign Minister Anthony Eden and the new Minister for Aircraft Production, Lord Beaverbrook , to use Hess for propaganda purposes not against the Nazi regime, but against the Soviet Union, allied with it. Because it was known that Stalin feared cooperation between the capitalist states against the Soviet Union, the British government spread rumors that the Hessian mission would be successful and that Germany was about to turn eastwards. To this end, Churchill had the false information spread that Hess would be the last in a long line of prominent prisoners to be held in the 900-year-old fortress in the Tower . The public statement on the Hess flight announced by Churchill did not materialize, and Beaverbrook instructed the press to spread as much speculation, rumors, and discussion about Hess as possible. When the Soviet Ambassador Iwan Maiski asked the Foreign Office how the government felt about Hess's peace offer, the Parliamentary Undersecretary of State Rab Butler was so reserved that the Ambassador believed that a peace treaty between Germany and Great Britain was imminent. With this disinformation policy , the British wanted to get Stalin either to turn away from his National Socialist ally and to establish a common defensive front together with Great Britain or to start a preventive strike against Germany, which would then have to wage a two- front war .

This confusion contributed to the fact that Stalin did not take reports in the run-up to the German attack on June 22nd seriously. Not only had Richard Sorge reported from Tokyo, but Foreign Minister Eden had also passed on the findings of the deciphering specialists in Bletchley Park to the Soviets since June . On July 12th, a military alliance with the Soviet Union ended British isolation: the German attack had changed the framework in favor of Great Britain, and so the British "game with Rudolf Hess as a figure on the chessboard of the crisis situation of early summer 1941" was up.

With increasing length of imprisonment, Hess became more and more convinced that he should be murdered. He developed an on paranoia bordering afraid that they wanted him poison. Sometimes he insisted on sharing his food with the MI6 officers. Hess's questionable behavior led the guards to believe that he was possibly insane. The psychiatrist John Rawlings Rees came to the conclusion after a personal interview that Hess was mentally ill and suffered from depression . In his captive diaries there are many references to visits from Rees, whom he disliked. He accused Rees of trying to "hypnotize" and poison him.

post war period

Nuremberg Trials

In the Nuremberg trials, Hess was sentenced to life imprisonment for planning a war of aggression and a conspiracy against world peace and was transferred to the Allied military prison in Berlin-Spandau .

Hess initially claimed in Nuremberg to suffer from "progressive amnesia", whereupon a commission was formed to examine his health. The commission agreed that Hess did indeed suffer from amnesia. When the request was made to suspend the proceedings against him, he surprisingly stated that from now on his memory would be available to the outside world again. He had only faked his amnesia for tactical reasons and originally reserved this explanation for a later date, but wanted to prevent the proceedings against him from being closed as a result.

Thereupon the application to suspend the proceedings against Hess was rejected. Nevertheless, the prison psychologist Gustave M. Gilbert determined again on August 17, 1946 that Hess was suffering from amnesia.

When confronted with the atrocities in the concentration camps, Hess showed himself unshaken. In his closing remarks at the Nuremberg trial, he denied the prosecutors the right to deal with “internal German matters” that would not concern foreigners. All allegations against the German people are basically "honors", since they come from Germany's opponents. Hess happily confessed to having served under Hitler, "the greatest son [...] that my people produced in its thousand-year history" and having done his "duty as a German, as a National Socialist, as a loyal follower of my Führer". He doesn't regret anything.

Imprisonment in the Spandau war crimes prison

Hess and the six other war criminals sentenced to prison were taken to the Spandau War Crimes Prison on July 18, 1947 , which the Allies had set up specifically to accommodate the convicted in the British sector of Berlin . As before in the leadership of the National Socialists, the rivalries among the prisoners continued, so that small groups formed. But Hess remained an outsider, since his personality had anti-social features and he was recognizably mentally unstable. He was the only one who mostly stayed away from the services in the prison chapel. He also avoided any kind of work in prison that he considered beneath his dignity, thereby causing displeasure among his fellow inmates.

He was also a paranoid hypochondriac . He kept believing that they were trying to poison him, so he never took the portion of food that was meant for him. He often screamed and moaned day and night because of pain, the authenticity of which was doubted by both his fellow prisoners and the prison administration, since Hess let himself be immobilized with placebos and it was therefore assumed that the pain was simulated or psychosomatic . The inmates Erich Raeder , Karl Dönitz and Baldur von Schirach saw them as calls for help to attract attention or as a method of refusing to work. Because of his condition, Hess received some privileges and was allowed to stay away from some work, which caused the annoyance of the others.

Albert Speer and Walther Funk were more likely to meet him. Speer, also an outsider, made himself unpopular with the others by tolerating this behavior by Hess and even defending him before the prison guards. Hess was the only one of the prisoners to refuse to receive visitors for over twenty years. It was not until 1969 that he was ready to see his wife and his now grown-up son Wolf Rüdiger Hess when a necessary hospital visit was made outside the prison .

Erich Raeder and Walther Funk had also been sentenced to life imprisonment. Both were released early in 1955 (Raeder) and 1957 (Funk) because they were in poor health. Both died in 1960. Hess, on the other hand, remained imprisoned, and when Speer and Schirach were released in 1966 after having served their full sentences, he remained the only prisoner. Concerned for his mental health, the prison directors agreed to ease the previously harsh detention conditions. He was allowed to move into a larger cell and was given a kettle so that he could make tea or coffee at any time. Furthermore, his cell was no longer locked, giving him permanent access to the prison washing facilities and the prison library.

Dismissal requests and inquiries

Requests for early release from captivity failed due to the veto of the Soviet Union . Even undoubtedly anti-National Socialist personalities criticized Hess's treatment. For example, Winston Churchill wrote in his 1950 book, The Grand Alliance , that he was happy not to be responsible, since Hess was not a criminal case but more a medical one. The British chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, Sir Hartley Shawcross , described the continued imprisonment of Hess as a "scandal" in 1977.

In 1977 the right-wing extremist Action Group Nationales Europe put him up as a candidate for the European elections .

In the 1970s and 1980s, politicians and church representatives campaigned for a release on humanitarian grounds, also to prevent being transfigured as a martyr. Shortly before leaving office in 1974, Federal President Gustav Heinemann wrote to the heads of government of the Allies. On Hess's 90th birthday in 1984, the federal government requested clemency. In his Christmas address in 1985, the then Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker asked for mercy for Hess. Weizsäcker had originally planned to demand the release of Hess in his famous May 8, 1985 speech . Weizsäcker's press spokesman and speech writer Friedbert Pflüger had initially prevented this with reference to the Bitburg controversy that had just flared up at the time . On April 13, 1987, a few months before Hess' death, Der Spiegel reported that Mikhail Gorbachev was planning his release.

Rudolf Hess' son Wolf Rüdiger Hess tried all his life to obtain the release of his father and better conditions in prison. In 1967 he founded the relief community freedom for Rudolf Hess . Max Sachsenheimer was elected first chairman . The Rudolf Hess Society emerged from it in 1989 , the aim of which is to revise Hess's historical account and to clarify allegedly hushed up circumstances of his imprisonment and death. Wolf Rüdiger Heß was chairman of the company until his death on October 24, 2001. Since then, his widow has been acting on a temporary basis.

The Rudolf-Hess-Gesellschaft tried in vain to obtain the release of locked British files for Hess. Although blocking periods of 30 years, and more for personal archive material , are quite common in archives , neo-Nazi or historical revisionist publications such as the video film Hess's Secret Files from 2004 suspect that the British authorities did not want to release these files in order to gain background information about Hess 'To cover up flight and death, which could cast a negative light on the role of the British.

The files were released by the British National Archives after the lock-up period expired in July 2017 .

Death and cause of death

Hess made at least four suicide attempts. On June 16, 1941, he threw himself from a balcony in Mytchett Place , on February 4, 1945, he stuck a bread knife in his chest, on November 26, 1959, he smashed his glasses and cut his wrists with one of the broken pieces. on February 22, 1977 he did the same with a knife.

On August 17, 1987, Hess killed himself by hanging himself with an extension cord attached to a window handle. That day, as he did every day, he had taken a walk in the prison garden. In the middle there was an approximately 15 m² large gazebo with a glass facade, armchair, table and heating. In this he seemed to rest a little. Shortly afterwards a guard found Hess with the cable attached to the window around his neck.

In an allied press release that had been prepared for a long time and that was published immediately afterwards, it was said that Hess had "died in prison". More details were released the following day. Allegedly, the Soviet Union initially opposed this. Hess's body was autopsied on the same day by British coroner James Cameron.

Shortly before his death in 1987, Hess had expressed the wish to be buried in his parents' grave in the evangelical cemetery in Wunsiedel . Although he had never lived in the city, his wish was granted for the Christian motivation not to judge beyond death.

When the lease for the Hess grave in Wunsiedel was due for renewal, it was terminated on October 5th, 2011 by the Evangelical parish in Wunsiedel. Linked to this was the hope that the interest of neo-Nazis in marches in Wunsiedel would continue to wane. With the consent of the Heß 'heirs, the entire grave site was closed on July 20, 2011. Hess' bones were exhumed , burned and then buried at sea .

reception

Popular scientific literature

The British had originally locked their files on Hess until 2018 , which seemed to contradict their repeated claim that he had not brought any substantive information or offers with him. Therefore, popular scientific literature with various conspiracy theories has long flourished . The English historian John Costello argues that the British secret services should have been informed of the Hess flight, otherwise Hess would not have been able to overcome the British air defense. According to Costello's research, von Hess's flight was the result of an operation by the British secret services, which had suggested to some representatives of the National Socialist regime that there were circles in England, especially among the aristocracy , who could exert pressure to achieve a negotiated peace. Richard Deacon, a pseudonym of the British journalist Donald McCormick, wants a testimony from the naval agent and James Bond inventor Ian Fleming , who died in 1964 , according to which the British secret service encouraged the occultist Hess to fly with a fake horoscope . Fleming found Hess as the best candidate among the gullible, leading National Socialists because he dealt with astrology and wanted peace with England in order to protect Germany from the stresses of a war against Russia. The British doctor Hugh Thomas is of the opinion that Hess was shot down shortly after the start; arrived in Scotland and was convicted in Nuremberg was in truth a doppelganger . The historical revisionist Martin Allen takes the view that the peace initiative, which Hess regarded as promising, was torpedoed by Churchill, who in his opinion was actually the culprit in the Second World War, because he had promised himself the final annihilation of Germany if the Soviet Union and the USA entered the war. He backed these theses with papers in the British National Archives, which turned out to be forgeries . Allen's theses are also disseminated in the video documentation Secret Files Heß by the NPD historian Olaf Rose and the former communication scientist, including a member of the right-wing fraternity Danubia Munich , Michael Vogt .

Doubts about the cause of death

Relatives said that Hess, 93 years old at the time of his death, was hardly able to walk, tie his shoes or raise his arms above shoulder height without the help of his carer, so that suicide was impossible. They therefore believe that Hess was murdered by the British Secret Intelligence Service in a fake suicide. For this reason, the family commissioned a second autopsy two days after Hess's death , which was carried out in the Institute for Forensic Medicine at the University of Munich by the well-known forensic doctors Wolfgang Spann and Wolfgang Eisenmenger . The question raised by the family as to whether the patient had been strangled or hanged could not be answered by the expert opinion, as important throat viscera such as the larynx, trachea, thyroid and a carotid artery were missing as a result of the British first autopsy and it was no longer possible to differentiate in retrospect whether the present was Force against the neck was caused by hanging or strangling. Evidence of a murder was not found at the autopsy. However, Spann criticized some details of the first autopsy and classified the strangulation marks as atypical for hanging. This is seen as evidence by proponents of the murder thesis. Hess' last nurse Abdallah Melaouhi and the prison director Eugene Bird , who was removed from office in 1972, are presented as witnesses by the proponents of the murder theory. Bird had already published his book Rudolf Hess: Stellvertreter des Führers in 1974 , Melaouhi published his book I saw the murderers in the eyes in 2008 in cooperation with the member of the national board of the NPD Olaf Rose ! The last few years and the death of Rudolf Hess . Since then he has lectured to neo-Nazis. In 2008, one of Hess's confessors, the French military chaplain Michel Roehrig, made his first statement. He was convinced that Hess had committed suicide; In the end he had been very depressed, had no longer believed in a pardon and could no longer bear his physical decline.

Effects on the neo-Nazi scene

In the neo-Nazi scene, due to his unbroken commitment to National Socialism, his 46-year imprisonment and the conspiracy theories surrounding his flight to Great Britain as well as his death, Hess is a martyr and "peace aviator". As an example of the “ apologetically absurd” view of Hess that is widespread in neo-Nazi circles, Rainer F. Schmidt cites the counterfactual speculation of his son Wolf Rüdiger Hess, according to which, if his flight to Great Britain was successful, “the German attack on the Soviet Union would not take place "And the" European Jewish question "would have been brought to a peaceful solution. The anniversary of his death had been the occasion for neo-Nazi marches every year since 1987, the so-called Rudolf Hess memorial marches in the Upper Franconian town of Wunsiedel , where Rudolf Hess was buried. From 1988 to 1990 rallies were held with the approval of the Bayreuth Administrative Court. From 1991 to 2000 the demonstrations were banned and, despite the bans, took place in other cities and also in other countries (such as the Netherlands and Denmark). In 2001 the demonstrations in Wunsiedel were allowed for the first time and, with around 2500 participants in 2002 and 3800 participants in 2004, were among the largest neo-Nazi demonstrations in Germany. The demonstrations during these years were also approved by the Federal Constitutional Court .

In order to show that they do not identify with these marches, citizens of Wunsiedel organized counter-demonstrations and founded citizens' initiatives that advocate tolerance, engagement and civil courage . An amendment to the Criminal Code in 2005, which made the approval, justification or glorification of National Socialist rule a criminal offense, made it possible to ban the marches. In 2005 and 2006 the parade was again banned. This decision was confirmed both times by the Bayreuth Administrative Court , the Bavarian Administrative Court and the Federal Constitutional Court (see also the Wunsiedel decision ). Since then, there have only been silent marches with a small number of participants in Wunsiedel.

Since the 20th anniversary of death in 2007 was of particular symbolic importance, demonstration bans were imposed in advance in numerous places in Germany, and the organizers challenged them in court. No demonstrations were allowed to take place anywhere in Saxony-Anhalt . In Munich , a parade was permitted subject to conditions. The Forchheim district appealed against the decision of the Bayreuth Administrative Court to the Bavarian Administrative Court to allow a demonstration in Graefenberg .

In the book Les 7 de Spandau (Die Sieben von Spandau) , published in 2008, Charles Gabel and Michel Roehrig, Hess's last confessors, stated that Hess himself repeatedly called neo-Nazis who demonstrated for him “fools”. In the second half of his 40-year imprisonment, he had undergone a profound change and in the end had nothing to do with a National Socialist or anti-Semite .

literature

Biographical / general

- Eugene Bird : Hess. The deputy of the Führer. Flight to England and British captivity. Nuremberg and Spandau. Kurt Desch, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-420-04701-0 .

- Rudolf Heß: Letters 1908–1933, ed. by Wolf Rüdiger Heß, with insertions and comments by Dirk Bavendamm , Langen, Müller, Munich / Vienna 1987, ISBN 3-7844-2150-4 .

- Peter Longerich : Hitler's deputy. Leadership of the party and control of the state apparatus by the Hess staff and the party chancellery Bormann. KG Saur, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-598-11081-2 .

- Dietrich Orlow : Rudolf Hess. "Deputy of the Führer". In: Ronald Smelser , Rainer Zitelmann (Ed.): The brown elite I. 22 biographical sketches. 3rd edition, Wiss. Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1994, ISBN 3-534-80036-2 , pp. 84-97.

- Kurt Pätzold and Manfred Weißbecker : Rudolf Heß - The man by Hitler's side. Militzke, Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-86189-157-3 Paperback edition Militzke 2003. ( Review by Armin Nolzen ).

- Alfred Seidl : The Hess case 1941–1987. Documentation of the defense attorney. 3rd edition, Universitas, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-8004-1066-4 .

"England flight"

- Jo Cox: Propaganda and the Flight of Rudolf Hess, 1941-45. In: Journal of Modern History. Vol. 83, 2011, pp. 78-110 ( doi: 10.1086 / 658050 ).

- James Douglas-Hamilton : Secret Flight to England - The "Messenger of Peace" Rudolf Hess and his backers. Droste, Düsseldorf 1973, ISBN 3-7700-0292-X .

- Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Hitler on the Hess case before the Reich and Gau leaders on May 13, 1941. Documentation of the Knoth postscript. In: past and present. Quarterly books for contemporary history, social analysis and political education , number 18 (1999) 95–100 [Wilhelm Knoth was Gauamtsleiter in Kassel].

- Roy Conyers Nesbit, Georges Van Acker: The Flight of Rudolf Hess: Myths and Reality. Sutton Publishing, 1999, Rev. Paperback Ed. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7509-4757-2 .

- Armin Nolzen : The Hess flight of May 10, 1941 and public opinion in the Nazi state. In: Martin Sabrow (ed.): Scandal and dictatorship. Public outrage in the Nazi state and in the GDR. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 978-3-89244-791-7 .

- Rainer F. Schmidt : Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Foren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. 3rd edition. Econ, Düsseldorf 2000, ISBN 3-430-18016-3 .

- Rainer F. Schmidt: The Hess flight and the Churchill cabinet. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . Volume 42, 1994, Issue 1, pp. 1-38 (PDF).

Significance in the neo-Nazi scene

- Thomas Dörfler, Andreas Klärner: The "Rudolf Hess Memorial March" in Wunsiedel. Reconstruction of a nationalist phantasm. In: Mittelweg 36 . Vol. 13, 2004, Issue 4, pp. 74-91 (online at Rechtssextremismusforschung.de ).

- Michael Kohlstruck : Fundamental Oppositional History Policy . The mythologization of Rudolf Hess in German right-wing extremism. In: Claudia Fröhlich, Horst-Alfred Heinrich (Ed.): History policy. Who are their actors, who are their recipients? Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08246-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Rudolf Heß in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Rudolf Heß in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Article about " Rudolf Hess " in the lexicon of right-wing extremism by Belltower.News

- Gabriel Eikenberg: Rudolf Hess. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG ), July 10, 2015

- Fabian Grossekemper: Rudolf Heß (1894–1987) at shoa.de , October 4, 2004

- Rudolf Heß in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Spektrum .de: Geneticists refute the “doppelganger theory” January 22, 2019

- Wolfram Stahl: ZeitZeichen : 08/17/1987 - anniversary of the death of Nazi politician Rudolf Hess

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt : Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 37 f.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 37.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf 3rd edition 2000, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf 3rd edition 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 40.

- ↑ a b c Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 40 ff.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, pp. 42-44.

- ↑ a b Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 44 f.

- ↑ Joachim Fest: Hitler - A Biography. Ullstein Taschenbuch, 10th edition 2008, p. 183.

- ↑ Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): Führer befiehl ... self-testimonies from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP. Grondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1991, p. 22.

- ↑ a b Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 48 f.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 35 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Thamer : Seduction and violence. Germany 1933–1945. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1994, p. 66 ff.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte, Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2003, pp. 565, 560.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 51 f.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, pp. 52-55.

- ↑ Examples from Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): Führer befiehl ... Testimonials from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP. Grondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1991, pp. 168 ff., 205 u. ö.

- ↑ Henry Ashby Turner : The Big Entrepreneurs and the Rise of Hitler. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1985, p. 185.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 57.

- ↑ Henry Ashby Turner: The Big Entrepreneurs and the Rise of Hitler. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1985, p. 118 f.

- ^ A b c d e Robert Wistrich : Who was who in the Third Reich. Supporters, followers, opponents from politics, business, military, art and science. Harnack, Munich 1983, p. 120.

- ↑ a b Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 55 f.

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker : The flight of the paladin . In: Der Spiegel . No. 23 , 2001 ( online ).

- ↑ Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): Führer befiehl ... self-testimonies from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP. Grondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1991, p. 129 f.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, pp. 58-62.

- ↑ Carola Stern , Thilo Vogelsang , Erhard Klöss, Albert Graff (eds.): Dtv-Lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century. dtv, Munich 1974, p. 336.

- ↑ a b c Rudolf Hess. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ^ Yearbook of the Academy for German Law, 1st year 1933/34. Edited by Hans Frank. (Munich, Berlin, Leipzig: Schweitzer Verlag), p. 254.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 62 f.

- ↑ Martin Broszat : The state of Hitler: Foundation and development of its internal constitution. dtv, Munich 1969, p. 683.

- ^ Peter Longerich : Hitler's deputy. Management of the NSDAP and control of the state apparatus by the Hess and Bormann party chancellery. KG Saur, Munich 1992, pp. 109, 265 f.

- ^ Wolfgang Benz : National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) . In: the same, Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 603.

- ↑ Fabian Grossekemper: Rudolf Heß (1894–1987). shoa.de; accessed on May 28, 2015.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne : "Give me four years". Hitler and the beginnings of the Third Reich. Ullstein, Berlin 1996, p. 131 f.

- ↑ Reinhard Bollmus: Deputy of the Führer. In: Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml, Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 748.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 63 f. and 77 (here the quote)

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, pp. 66-69.

- ↑ a b Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 77 (here the quote) - 85.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 74 f.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: "Give me four years". Hitler and the beginnings of the Third Reich. Ullstein, Berlin 1996, p. 95.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 69.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: "Give me four years". Hitler and the beginnings of the Third Reich. Ullstein, Berlin 1996, p. 99 ff.

- ↑ a b Peter Longerich : The brown battalions. History of the SA. Beck, Munich 1989, p. 203.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 70.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Thamer: Seduction and violence. Germany 1933–1945. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1994, p. 330.

- ↑ Martin Loiperdinger : "Triumph of the Will". Settings log. In: David Culbert (Ed.): Leni Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will". University Publications of America, Frederick MD 1986, p. 133.

- ↑ a b Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf 3rd edition 2000, p. 72.

- ↑ Götz Aly , Wolf Gruner et al. (Ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 . Vol. 1: German Empire 1933–1937. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, Doc. 27.

- ↑ Cornelia Essner: The "Nuremberg Laws" or The Administration of Rassenwahns 1933-1945. Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, p. 66 ff.

- ↑ a b Götz Aly, Wolf Gruner et al. (Ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Vol. 1: German Empire 1933–1937. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, Doc. 131.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Politics of Destruction. An overall presentation of the National Socialist persecution of the Jews. Piper, Munich 1998, p. 104.

- ↑ Uwe Dietrich Adam: Jewish policy in the Third Reich. Droste, Düsseldorf 1972, p. 145.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Foren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf 3rd edition 2000, p. 72 f.

- ↑ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf 3rd edition 2000, p. 73 f.

- ↑ Cornelia Essner: The "Nuremberg Laws" or The Administration of Rassenwahns 1933-1945. Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, p. 248 f.

- ↑ Götz Aly, Wolf Gruner et al. (Ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Vol. 2: German Reich 1938 – August 1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, Doc. 313.

- ↑ Federal Minister of Justice (ed.): In the name of the people. Justice and National Socialism. - Exhibition catalog. Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-8046-8731-8 , p. 227.

- ↑ Hans J. Ebert, Johann B. Kaiser, Klaus Peters: Willy Messerschmitt - pioneer of aviation and lightweight construction. A biography. Bernard & Graefe, Bonn 1992, ISBN 3-7637-6103-9 , p. 161 f.

- ^ Susanne Meinl, Bodo Hechelhammer: Secret object Pullach. Christoph Links Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86153-792-2 , p. 55 ( Google Books )

- ↑ Joseph Howard Tyson: The Surreal Empire. Bloomington / Indiana 2010, ISBN 978-1-4502-4019-2 , pp. 279 ff. ( Google Books )

- ↑ Hans J. Ebert, Johann B. Kaiser, Klaus Peters: Willy Messerschmitt - pioneer of aviation and lightweight construction. A biography. Bernard & Graefe, Bonn 1992, ISBN 3-7637-6103-9 , p. 162.

- ^ Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Hitler on the Hess case ... Documentation of the Knoth postscript. In: Geschichte und Gegenwart 1999, pp. 95–100.

- ↑ Victor Klemperer : I want to bear witness to the last. Diaries 1933–1945. Structure, Berlin 1995, vol. 1, p. 594. Quoted by Henning Köhler : Germany on the way to itself. A story of the century. Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 388.

- ↑ a b Rainer F. Schmidt: The Hess flight and the Churchill cabinet. Hitler's deputy in the calculation of British war diplomacy May – June 1941. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 41 (1994), p. 14 f. ( online (PDF; 7.7 MB), accessed April 11, 2012).

- ^ Andreas Hillgruber : Hitler's strategy. Politics and warfare 1940–1941. Munich 1982, p. 514 ff .; Bernd Martin: Peace Initiatives and Power Politics in the Second World War. Droste, Düsseldorf 1976, p. 426; Klaus Hildebrand : German Foreign Policy 1933–1945. Calculus or dogma? Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Berlin and Cologne 1990, p. 111.

- ↑ Ralf Georg Reuth (Ed.): Joseph Goebbels. Diaries 1924–1945. Piper, Munich 1992, vol. 4, p. 1576 f. (Entry from May 15, 1941, misspellings in the original).

- ↑ "What was wanted at the moment [...] was as much speculation, rumor, and discussion about Hess as possible." Quoted by Rainer F. Schmidt: The Hess flight and the Churchill cabinet. Hitler's deputy in the calculation of British war diplomacy May – June 1941. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 41 (1994), pp. 17–20 (here the quote). ( online (PDF; 7.7 MB), accessed April 11, 2012)

- ↑ Gabriel Gorodetsky : Stalin and Hitler's attack on the Soviet Union. In: Bernd Wegner (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow. From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to "Operation Barbarossa". Piper, Munich 1990 p. 352 f.

- ↑ Gabriel Gorodetsky: Stalin and Hitler's attack on the Soviet Union. In: Bernd Wegner (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow. From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to "Operation Barbarossa". Piper, Munich 1990 p. 352-358.

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: The Hess flight and the Churchill cabinet. Hitler's deputy in the calculation of British war diplomacy May – June 1941. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 41 (1994), p. 19. ( online (PDF; 7.7 MB), accessed on April 11, 2012)

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: The Hess flight and the Churchill cabinet. Hitler's deputy in the calculation of British war diplomacy May – June 1941. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 41 (1994), pp. 29–39 (the quotation p. 37 f.). ( online (PDF; 7.7 MB), accessed April 11, 2012)

- ^ Minutes of the main hearing on November 30, 1945 (afternoon session)

- ^ Whitney Harris : Tyrants in front of the court : the proceedings against the main German war criminals after the Second World War in Nuremberg 1945-1946. from the American by Christoph Safferling and Ulrike Seeberger. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-8305-1593-7 .

- ↑ Hess' closing remarks on August 31, 1946 ( memento from November 5, 2011 on WebCite ) (accessed on April 15, 2012)

- ↑ Friedbert Pflüger: Richard von Weizsäcker - A portrait up close . 1st edition, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-426-02437-3 , pp. 202-206, p. 203 in the Google Book Search

- ↑ Does Gorbachev release Hess? In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1987 ( online ).

- ↑ Wolf Rüdiger Hess: Rudolf Hess: "I have no regrets" . Stocker Leopold Verlag, 1994, ISBN 978-3-7020-0682-2 , p. 42 ( google.de [accessed on April 23, 2019]).

- ↑ Files released: Cabinet Office files from 1991 and Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The National Archives, News, July 20, 2017.

- ^ Conyers Nesbit, Van Acker, p. 97.

- ↑ Albert Speer : Spandau Diaries. Ffm / Bln / Vienna 1975, p. 518 f.

- ↑ Wolf Rüdiger Hess: My father Rudolf Hess. Flight to England and imprisonment. Langen Mueller, Munich / Vienna 1984, pp. 324, 361, 425.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml, Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 845.

- ^ Radio Bremen Eins - As Time goes by: August 17th, 1987 - The deputy resigned.

- ^ A b c Alexandra Gerlach, Annette Wilmes , Michael Watzke : Under police protection - Dresden and the neo-Nazi marches , Deutschlandfunk - " Background " from February 17, 2011

- ^ Grave of Hitler's deputy dissolved Merkur.de , updated on September 19, 2018

- ^ Süddeutsche Zeitung : Wunsiedel: End of a Nazi pilgrimage site - Rudolf Hess's grave no longer exists.

- ↑ Also on the following Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, pp. 19-26.

- ^ John Costello: Ten Days That Saved the West. Bantam Press, London 1991, p. 414 ff.

- ^ John Costello: Ten Days That Saved the West. Bantam Press, London 1991, p. 19 and chapter 17.

- ^ Richard Deacon: A History of the British Secret Service. New York, Taplinger 1969, p. 307 ff.

- ↑ Anthony Masters: The Man Who Was M. The Life of Maxwell Knight. Bais Blackwell, Oxford / New York 1984, p. 127.

- ^ Hugh Thomas: The murder of Rudolf Hess. Harper & Row, London 1979.

- ↑ Martin Allen: The Hitler / Hess Deception: British Intelligence's Best Kept Secret of the Second World War. HarperCollins, London 2003.

- ↑ Ernst Haiger: Fiction, Facts, and Forgeries. The "Revelations" of Peter and Martin Allen about the History of the Second World War. In: The Journal of Intelligence History 6, (2006), pp. 105-117.

- ^ ZDF history : The Hess file. Documentation, 2012, video on YouTube . See Patrick Gensing : Hess files: The ZDF, Höffkes and the Völkerringen. In: Publikative.org , November 6, 2012.

- ↑ Brigitte Emmer: Hess' flight to England. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Legends, Lies, Prejudices. A dictionary on contemporary history. dtv, Munich 1994, p. 95.

- ↑ Katrin Lange: Rudolf Heß's last carer is thrown out of the migration advisory board. In: Die Welt , July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Book about the "confessors" by Rudolf Hess. In: Die Presse , September 29, 2008; Patrick Gensing : Military chaplain: “Hess repeatedly called neo-Nazis fools” ( Memento from May 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: Publikative.org , October 1, 2008.

- ↑ cf. BVerwG, judgment of June 25, 2008 - 6 C 21.07 marginal no. 6th

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt: Rudolf Heß - "Errand eines Toren?" The flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941. Econ, Düsseldorf, 3rd edition 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ Battle for the deployment area. In: Spiegel Online , August 16, 2007.

- ↑ It was suicide. In: n-tv . September 29, 2008, accessed August 31, 2016 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hess, Rudolf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hess, Rudolf Walter Richard (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (NSDAP), MdR, Hitler's deputy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 26, 1894 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Alexandria , Egypt |

| DATE OF DEATH | 17th August 1987 |

| Place of death | Berlin-Spandau |