On the 40th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe and the National Socialist tyranny

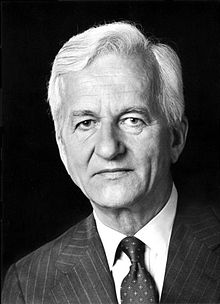

On the 40th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe and the National Socialist tyranny , the title of a historic speech given by the then Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany Richard von Weizsäcker on May 8, 1985 at the memorial hour in the plenary hall of the German Bundestag .

With the statement contained in his speech about the liberation from National Socialism , von Weizsäcker coined a key statement of the culture of remembrance in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Emergence

The fortieth anniversary of the end of the war coincided with a planned visit to Germany by American President Ronald Reagan . The Chancellery and the White House considered holding Remembrance Day with Reagan. At Weizsäcker's request, among other things, it was decided to do it in the Bundestag without foreign participation, but among Germans. Reagan made his state visit a few days before May 8th. He visited the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and then the military cemetery in Bitburg with Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl . Only after Reagan's acceptance to Bitburg did it emerge that members of the SS were also buried in this cemetery . Reagan got into severe political difficulties in the USA (see Bitburg controversy ). According to Weizsäcker, this event showed “the full extent of the sensitivity in dealing with the past”. The speech that Weizsäcker gave three days after Kohl and Reagan's appearance was variously understood as the “answer to Bitburg”.

During the four months of preparation for the speech, von Weizsäcker held talks with representatives of the political parties as well as representatives of churches and associations of expellees and victims of National Socialism. As he wrote in his memoirs, he worked most intensively with a diplomat from the Foreign Service , Michael Engelhard .

His press spokesman at the time, Friedbert Pflüger , repeatedly described that von Weizsäcker had planned to demand a pardon for Rudolf Hess in his speech . With reference to the Bitburg controversy, Pflüger persuaded the Federal President to delete the demand for the release of Hitler's deputy.

Content and form

With the words “There was no ' zero hour ', but we had the chance to start over. We used them as best we could. We have put democratic freedom in place of bondage, ”Weizsäcker drew the sum of forty years of West German post-war history in this speech. He emphasized that the Federal Republic of Germany had found its place among the states with a democratic constitution in the western tradition. That had been seen differently in the course of those forty years.

The speech is divided into nine sections, in which von Weizsäcker approaches the 40th anniversary of the so-called German surrender from different perspectives.

Von Weizsäcker makes it clear that the day the war ended in Europe, which is perceived differently by every people, was not a day of defeat for the Germans, but a "day of liberation from the inhuman system of National Socialist tyranny". May 8th and its aftermath, which also meant the division of Germany, were inextricably linked to the beginning of the National Socialist dictatorship in Germany in 1933.

Von Weizsäcker rejects collective guilt : "Guilt, like innocence, is not collective, but personal". However, he speaks of a “heavy inheritance” left by the ancestors of the current generation and calls on all Germans to embrace the past.

Von Weizsäcker emphasizes the role of women who would have carried “perhaps the largest part of what was charged to people”.

The ruthlessness and openness with which von Weizsäcker analyzed the causes that led to the war, the Holocaust, the expulsion of ethnic groups and the divided Europe and drew the consequences for the present from it, was until then for a public speech by a German head of state without example.

Von Weizsäcker concluded the speech with these words

“Hitler always worked to stir up prejudice, enmity and hatred.

The request to young people is:

Do not let yourself be driven into hostility and hatred

of other people,

of Russians or Americans,

of Jews or Turks,

of alternatives or conservatives,

black or white.

Learn to live together, not against each other.

Let us as democratically elected politicians take this to heart again and again and set an example.

Let's honor freedom.

Let's work for peace.

Let's keep the law.

Let us serve our inner standards of righteousness.

Let's look the truth in the eye as best we can on May 8th today. "

effect

The speech met with an extraordinary response and overwhelming approval at home and abroad. It caused a sensation in Israel in particular . From the Israeli embassy in Bonn it was said that the speech had been a “great moment in German post-war history”. The speech paved the way for Richard von Weizsäcker's state visit to Israel in October 1985, the first state visit to that country by a German Federal President. On May 23, 1985, Reinhard Appel said in the ZDF program Citizens Ask ... that the speech made it possible for him to “feel his own cosmopolitan fatherland”. The speech, which was televised several times, was translated into more than twenty languages and distributed to interested citizens in a print run of over two million copies, and it was also released on audio carriers. More than 60,000 citizens wrote to the Federal President. To this day, the speech has been highlighted as one of the most important achievements of Weizsäcker during his tenure as Federal President.

Criticism from the Union and the FDP

The speech met with criticism from parts of the Union. The CSU member of the Bundestag Lorenz Niegel and 30 other members stayed away from the speech. In 1986 Alfred Dregger spoke out against seeing May 8, 1945 unilaterally as a day of liberation. Even Franz Josef Strauss disagreed von Weizsäcker and demanded to leave the past "into oblivion, or reverie" disappear, because "the eternal with the past as a social life penitent Rauf gift paralyzes a nation!".

In 1995 the appeal “8. May 1945 - against forgetting ”published in the FAZ, which more than 200 signatories joined, including Alfred Dregger, Heinrich Lummer , Carl-Dieter Spranger and Alexander von Stahl . The signatories speak out against an image of history that is only fixed on “liberation”, because this cannot “be the basis for the self-understanding of a self-confident nation”.

Evaluation of the address

In the discussion of historians with German politics of the past , the speech met with not only a lot of approval but also criticism. Heinrich August Winkler praised it in 2000 as “liberating”, but “some [...] remain unsaid”, especially in connection with the involvement of the old elites in the destruction of the Weimar Republic and Hitler's successes. In this context he referred to Ernst von Weizsäcker , the speaker's father, who was State Secretary in the Foreign Office from 1938 to 1945 . Henning Köhler criticized in 2002 that Weizsäcker had elevated May 8 to the day of liberation and thus created “the fiction of an anti-fascist Germany that had been liberated by the Allies”. In truth, the Red Army had brought new “countless crimes ” over the majority of Germans , and the troops of the Western Allies were strictly forbidden from appearing as liberators. Michael Hoffmann complained in his dissertation in 2003 that formulations such as the “responsibility of the German people” remained general, vague and therefore without consequences. Theses such as anti-Semitism , which “stood at the beginning of the tyranny”, are questionable, Weizsäcker's handling of the ambiguous word people is problematic, his “recourse to the Jewish religion as a paradigm for a successful way of dealing with the past” is not -Jewish Germans hardly comprehensible, the term of reconciliation used in this context irritating: Weizsäcker operates "with metaphysical categories that stifle further considerations about the how and why of the past". The cultural scientist Matthias N. Lorenz admitted in 2007 that the speech brought an important turning point in the German culture of remembrance, but criticized the fact that the Federal President narrowed the Nazi perpetrators solely “to Hitler and his ruling class”. All others only appeared as "seduced". Here the results of the controversy between intentionalists and functionalists were not reflected.

literature

- Ulrich Gill, Winfried Steffani (Ed.): A speech and its effect. The speech of Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker on May 8, 1985 on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. Those affected take a position . Verlag Rainer Röll, Berlin, ISBN 3-9801344-0-7 .

- Cornelia Siebeck: "Entry into the Promised Land". Richard von Weizsäcker's speech on the 40th anniversary of the end of the war on May 8, 1985. In: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History. 12, 2015, pp. 161-169.

Web links

- Complete text of the speech (online presence of the Federal President's Office )

- Recording of Weizsäcker's speech on May 8, 1985 - Internet Archive (audio document as MP3 / 160 Kbits, 44:32 minutes)

- Record recording of the aforementioned Weizsäcker speech from 1985 on youtube.com (audio document in 4 parts, approx. 45 minutes in total)

- Video version of the Weizsäcker speech on May 8, 1985, created by the Phoenix broadcaster on youtube.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ Richard von Weizsäcker: Four times. Memories , Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-88680-556-5 , p. 318.

- ^ Christian Mentel: Bitburg Affair (1985). In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.) Handbook of Antisemitism , Vol. 4: Events, Decrees, Controversies . de Gruyter Saur, Berlin / New York 2011, ISBN 978-3-598-24076-8 , p. 52 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ webarchiv.bundestag.de Web archive of the German Bundestag: Address by Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker on May 8, 1985 in the plenary hall of the German Bundestag on the 40th anniversary of the end of the Second World War .

- ↑ “The Day of Liberation” - Weizsäcker's most famous speech. In: Der Spiegel. May 8, 2005.

- ^ A b Great moment in post-war history - The Weizsäcker speech of 1985. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. May 7, 2005.

- ^ Tobias Kriener: Christian-Jewish dialogue and German-Israeli relations. Chapter 10.

- ↑ a b Forgiveness granted. Der Spiegel , November 24, 1986, accessed November 18, 2017 .

- ↑ Full truth. Der Spiegel, April 17, 1995, accessed November 18, 2017 .

- ↑ The annoying mission statement. Die Zeit , December 5, 1986, accessed on November 18, 2017 .

- ↑ 8 May 1945 redeemed and destroyed. Focus , April 3, 1995, accessed November 18, 2017 .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. German history II. From the “Third Reich” to reunification . CH Beck, Munich 2014, p. 442 f.

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century . Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 638 f.

- ↑ Michael Hoffmann: Ambivalences of the interpretation of the past. German speeches about fascism and the 'Third Reich' at the end of the 20th century . Diss. Gießen 2003, p. 8 f. and 24-52.

- ^ Matthias N. Lorenz and Daniela Beljan: Weizsäcker speech. In: Torben Fischer and Matthias N. Lorenz (eds.): Lexicon of 'coping with the past' in Germany. Debate and discourse history of National Socialism after 1945. 3rd, revised and expanded edition, transcript, Bielefeld 2015, ISBN 978-3-8376-2366-6 , p. 255 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).