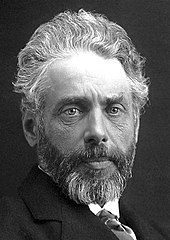

Henrik Pontoppidan

Henrik Pontoppidan (born July 24, 1857 in Fredericia , † August 21, 1943 in Copenhagen ) was a Danish writer who stood out primarily as a narrator. With Hans im Glück , initially published in eight volumes between 1898 and 1904, he created “one of the most extensive and important novels in Danish literature”. In 1917 he received the Nobel Prize.

Life

Pontoppidan came from a Grundtvigian pastor's house. He spent most of his childhood in the East Jutland port town of Randers near Aarhus , which can also be found encrypted in his main work, Hans im Glück . Similar to his hero, Pontoppidan took an engineering degree at the Copenhagen Polytechnic , which he did not complete. He initially made a living as a folk high school teacher and journalist. He made his narrative debut in 1881 in the illustrated weekly newspaper Ude og Hjemme . In the same year he married Mette Marie Hansen (1855-1937). He toured Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In 1884 he had his first personal encounter with the anti-clerical philosopher and literary critic Georg Brandes , who not only strongly influenced Pontoppidan. In his key work Hans im Glück , Pontoppidan has "a sympathetic and impressive" portrait of Georg Brandes in the figure of Dr. Given to Nathan.

Pontoppidan moved frequently in his life, sometimes living in the countryside, sometimes in Copenhagen. The Danish state granted him at least part of the living allowance. In 1892 they divorced Mette, with whom Pontoppidan had three children. In the same year he married Antoinette Kofoed (1862–1928), two children. This was followed by trips to Italy, Dresden , Norway - and numerous book publications. In 1917 Pontoppidan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his vivid descriptions of contemporary life in Denmark” . He had to share the price with Karl Gjellerup . In 1927 the Danish state granted him an honorary gift. In 1937 the Danish Writers' Union set up the Henrik Pontoppidan Memorial Fund . Pontoppidan, becoming increasingly deaf and blind as early as 1927, died (during the Second World War) at the age of 86.

Age did not prevent Pontoppidan from following current events, but it made him unmistakably gloomy. Life has to be suffered, we don't populate the country just for the sake of joy , Peter Urban-Halle quotes the elderly writer. “With this, Pontoppidan is almost taking up pietistic ideas again, he was a man of contrasts. That makes him seem a little torn, but it also makes his work more comprehensive. For him, the novel as a genre is a total structure that encompasses all currents of time and society. Although resignation and pessimism prevailed at the end of his life, he always remained a political writer. "

style

Pontoppidan used a simple and clear language, which, of course, was not without irony and profundity. Referring to Hans im Glück , Erhard Schütz even calls this “unpretentious” language “slightly out of date”. She has caution. Pontoppidan avoids judging his "heroes" more than with kid gloves - with which he redeemed his self-image, which he opened (in a preliminary remark to his novella Sturmlied from 1896) with a blow to the ubiquitous philosophers and priests of life.

“I know very well that it would be easier for me to find recognition from our doctoral literary critics if I - like more or less honored colleagues - disguised myself in such a sleepless brooder, in a profound windmaker, painfully impregnated with too great a fruit of thought. Nonetheless, I want to resist this temptation as well and renounce for time and eternity from being exalted to a poetic seer by the grace of God and the reviewers. Frankly, I prefer to be what I am: a person who above all loves clarity of thought and masculine balance of mind - a pedant, if you will, for whom the nourishing and renewal processes of his spiritual life are calm and run regularly without any flatulence caused by mental fermentation with the associated fearful pregnancy, with mood colic and the incessant worm-pinching of remorse, and which in any case does not allow himself to speak without having made sure that the pulse is normal and the Tongue is not covered. "

effect

Pontoppidan is an important representative of naturalism in Denmark. Thinkers like Georg Lukács , Ernst Bloch , Jean Améry held him in high regard and included him in their considerations. In addition to love, he mainly revolved around the contrast between culture and nature, and thus also between urban and rural areas. On the one hand, he welcomed the much touted “progress” around 1900; on the other, his equalizing, destructive, and indifferent traits worried him. It was also the epoch of cynicism , as it was concisely shown in the triumphant advance of the press and, more generally, of money (which Georg Simmel described at the same time). Pontoppidan stayed away from political parties. As for his Danish fatherland, he was a patriot .

The promised land

A pale and skinny young chaplain arrives in the small village of Vejlby, who has just passed his theological exam in Copenhagen and is starting his first job as an assistant pastor here in the rural rectory with the pastor and provost [dean] Tønnesen. This young pastor Hansted is warned about the revolutionary ideas for which the weaver Hansen is fighting, and Tønnesen also includes the home folk high school movement. The population living from fishing in Skibberup, the second preaching district with a lonely, decaying church, is particularly rebellious (and therefore far from any worship). Tønnesen's daughter Ragnhild, on the other hand, belongs to the conservative milieu, and she doesn't want to fit into this rural setting either. Hansted experiences community members far from culture. One is curious about the "new one", also has expectations (in memory of his late mother, who happened to be beneficial and unconventional in this place), but Emanuel Hansted clings to his equally conservative worldview. However, his attitude towards the poor congregation in Skibberup changes noticeably after he gets to know these people better, and he even lets himself be persuaded to pay a visit to the meeting house there and experience the devotion held there by the lay people. Here he meets the farmer's daughter Hansine, and he feels drawn to her. His whole behavior is an increasingly stronger break with the church world of the provost, which is solidified in hierarchical thinking.

On lonely hikes in wind and weather, Emanuel experiences his growing insecurity about the principles he has learned. Tønnesen confronts him and suggests that he leave the parish. Emanuel flees into a different life as a farmer and preacher in poor circumstances and finally with Hansine as his wife. However, he is supported by the unconventional bishop, who dismisses Tønnesen (honorably lets him assume a higher office), and Emanuel and Hansine move into the splendid rectory, which is transformed into a rural house. - In the conversation between Tønnesen and the bishop before, “ 1864 ” ( German-Danish War ) is mentioned, and this allows this first part of the trilogy of novels (the first book with the title Muld [Erde] published in 1891) to be categorized in terms of time and social history . The model for this bishop is Ditlev Gothard Monrad and his time at the end of the 1870s.

The second part, published in 1892, bears the title of the entire edition: Det forjættede land (The Promised Land). The translation "praised" (in Danish also associative with "enchanted") does not include for the German reader that the "Jætter" are those giants ( Jötunn ) against whom Thor and, in glorification of Old Norse, the Danish folk high school movement ( Heimvolkshochschule ) , led by Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundtvig , fought, especially in those decades after the national defeat of 1864. - Emanuel plows and evangelizes, the first untrained, the second with (apparently) growing success, so that he is “the modern apostle " is called. Personally, he suffers the misfortune of losing his beloved little son, and that too alienates the couple. Politically threatening clouds are gathering on the horizon [Pontoppidan loves painting depictions of nature], as the government recently fought for, again restricts democratic rights. The pastor also experiences how important pillars of his small congregation succumb to alcohol and gamble away their reputation.

After a long time, Emanuel and Ragnhild meet again. In the discussion of a group of visitors it emerges that Emanuel's vision largely failed. He remains the distant theologian and a stranger to his wife in the rural world. On the other hand, the pastor's daughter Ragnhild now tends to agree with his socio-political ideas and thus shocked her urban companions. However, even with Weber Hansen, doubts are growing as to whether Emanuel is really on the side of the rural population. Emanuel sticks to his faith and a god who determines his personal fate and thus finds himself further into the loneliness that lets him brood through the harsh nature, brooding. - There are still close contacts to the nearby Folk High School in Sandinge [Askov could be a model with the Folk High School that was moved here in 1865], and when the old adult education center director dies, the whole region meets at the grave, including countless guests from the capital. After various lectures, Emanuel comes to the lectern and his contribution is eagerly awaited. But he is not able to convince, and Weber Hansen agitates against him. Emanuel is close to collapse; he travels with his daughter to Copenhagen in the care of his elderly father. Hansine stays in Skibberup and takes care of her old parents. The experiment of being pastor and close to the people at the same time has obviously failed.

The third part of the novel trilogy is called Dommens Dag (The Day of Judgment); it appeared after a long break in 1895. - As is often the case in the novel, wind and weather coincide with the appropriate story about the characters involved: In the pouring rain, Emanuel visits the former pastor's office with his children, but avoids contact with Hansine and the little one too Sigrid only suspects that her mother, who is supposedly away, is close. - In the folk high school there are new personalities who have outgrown Emanuel's point of view. The discussion is determined by violent theological disputes. Then the Christ-like figure of Emanuel appears in the meeting, pale and gaunt, with a flowing beard and shoulder-length hair. Again Ragnhild Tønnesen plays a role and lets the shadows from the past come to life. The discussion with the conservative pastor accompanying her remains sterile for Emanuel. They also want to offer him a light pastoral position, but Emanuel does not want to bow to the yoke of the state church, but finds no personal peace. - Everyone meets again in the folk high school for a dispute that is supposed to clarify a crucial question of direction. Again Emanuel comes to the lectern and is celebrated by a small group of radical supporters with "Hosanna". The deathly pale preacher, visibly hardly from this world, can only collapse stammering with a “My God, why have you left me!”. A short time later he dies.

As a pastor's son who does not want to follow family tradition, the author Pontoppidan has obviously processed his own experiences. He relocated his novel to the time of his (engineering) studies and the years of his activity as a folk high school teacher. Det forjættede land (The Promised Land) is one of his three great novels and is called (with the first part) a "Zeitbild". All three parts appeared together in 1898 and in many editions since then. Editions relevant to the text appeared in 1918 and 1960. Here Pontoppidan depicts a Denmark of the 1870s; the following great novels Lykke-Per (Hans im Glück) and De dødes Rige (The realm of the dead) span the picture of the times and the description of the corresponding social, religious and political aspects up to the First World War.

Hans in hapiness

Between 1891 and 1916, Pontoppidan published Das gelobte Land , Hans im Glück, and Das Totenreich, three large-scale novels that reflect the social and religious struggles of the time and which, in his own words, are closely related. From this, Hans im Glück is usually highlighted as Pontoppidan's most important and most impressive work. Title hero Per Sidenius, who comes from an oppressively poor and pious background, wants to make the world sit up and take notice as an engineer, as the creator of a gigantic system of canals, bulwarks and ports. At first he succeeded in a few lucky sticks, for example to Jakobe, daughter from a very wealthy Jewish family, but finally he ended up as a nameless surveyor in self-chosen seclusion between dunes, where he, barely over 40 years old, was soon buried. For Winfried Menninghaus, like its author , the novel thus moves between “Poland revolt and resignation”. In the case of the hero of the novel, of course, they turn out to be incurable disruption. The worm does not sit in the social situation, rather Sidenius is at odds with himself, so that his numerous twists and turns and new attempts never get caught - for example in the arms of the country pastor's daughter Inger, who impresses him with her “unscrupulous practical sense” Henner Reitmeier writes.

“So it is the classic escape from oneself that Pontoppidan shows us with carefully considered words and considerable staying power. His hero is a pushover. Jakobe recognized it in time to keep Per off the neck. She only noticed the 'cold night side' of passion in him, namely defiance, egoism, obstinacy, but nothing stormy and consuming. Precisely with this, however, he had shown himself to be a 'perfect child of the dispassionate Danish people with the pale eyes and the fearful disposition' ... One of 'those mountain trolls who could not look into the sun without sneezing, who only really came to life in the dark when they sat on their molehills and conjured up rays of light in the evening light to comfort and edification for their afflicted senses ... '"

Works (German editions)

- A church robbery. Stories, Stuttgart 1890.

- The Sandinger community. Novella, 1883, 1905.

- Henrik the polar bear. Stories, 1887, Berlin 1903.

- The promised land. Roman, 1891/95, 1908, Jena 1922.

- Night watch. Narrative, 1894, 1896.

- Old Adam. Roman, 1894, 1912.

- Hans in hapiness. Roman, 1898–1904, Leipzig 1919.

- Little Red Riding Hood. 1900, 1904.

- Hans Quast. Roman, 1907, Tübingen 1929.

- The realm of the dead. Roman, 1912/16, Leipzig 1920, online Vol. 1 - Internet Archive , Vol. 2 - Internet Archive .

- The devil at the stove. 5 stories, Jena 1922.

- The royal guest. Story, Bremen 1982.

literature

- Vilhelm Andersen: Henrik Pontoppidan. Copenhagen 1917.

- Georg Brandes: Henrik Pontoppidan. In: Samlede Skrifter. Volume 3, Copenhagen 1919, pp. 310-324.

- Poul Carit Andersen: Henik Pontoppidan. En biographies and bibliographies. Copenhagen 1934.

- Ejnar Thomsen: Henrik Pontoppidan. Copenhagen 1944.

- Cai M. Woel: Henrik Pontoppidan. 2 volumes, Copenhagen 1945.

- Poul Carit Andersen: Digteren og mennesket. Fem essays om Henrik Pontoppidan. Copenhagen 1951.

- Niels Jeppesen: Samtaler med Henrik Pontoppidan. Copenhagen 1951.

- Knut Ahnlund: Henrik Pontoppidan. Fem huvudlinjer i forfatterskapet. Stockholm 1956.

- Karl V. Thomson: Hold galden flydende. Tankers and tenders in Henrik Pontoppidans forfatterskab. Copenhagen 1957 and 1984.

- Alfred Jolivet: Les romans de Henrik Pontoppidan. Paris 1960.

- Bent Haugaard Jeppesen: Henrik Pontoppidan's review of the fund. Copenhagen 1962.

- Elias Bredsdorff: Henrik Pontoppidan and Georg Brandes. 2 volumes, Copenhagen 1964.

- Elias Bredsdorff: Henrik Pontoppidan's relationship to radical thinking. In: Northern Europe. 3, 1969, pp. 125-142.

- Thorkild Skjerbæk: Art og budskab. Study in Henrik Pontoppidan's forfatterskab. Copenhagen 1970.

- H. Stangerup, FJ Billeskov Jansen (ed.): Dansk literaturhistorie. Volume 4, Copenhagen 1976, pp. 268-317.

- Jørgen Holmgaard (Ed.): Henrik Pontoppidans Forfatterskabets baggrund and udvikling belyst gennem 9 fortællinger. Copenhagen 1977.

- Svend Cedergreen Bech (ed.): Dansk Biografisk Leksikon. Copenhagen 1979-1984, volume 11, p. 441 ff.

- Philip Marshall Mitchell: Henrik Pontoppidan. Boston 1979 ( henrikpontoppidan.dk , accessed March 22, 2012).

- Johannes Møllehave: Den udenfor staende. Henrik Pontoppidan. In: Ders .: Lesehest med asselorer. Copenhagen 1979, pp. 172-194.

- Winfried Menninghaus: Afterword in the island edition by Hans im Glück. Frankfurt am Main 1981, pp. 817-874.

- KLaus P. Mortensen: Ironi and Utopi. En bog om Henrik Pontoppidan. Copenhagen 1982

- G. Agger et al. (Ed.): Dansk litteraturhistorie. Volume 7, Copenhagen 1984, p. 103 ff.

- Niels Kofoed: Henrik Pontoppidan's anarkisms and democracy tragedie. Copenhagen 1986.

- Jørgen E. Tiemroth: They are labyrinths. Henrik Pontoppidans forfatterskab 1881–1904. Odense 1986.

- Paul Pinchas Maurer: Jewish figures in the work of Henrik Pontoppidan . Jerusalem 2020.

Web links

- Literature by and about Henrik Pontoppidan in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Henrik Pontoppidan in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the awarding of the prize to Henrik Pontoppidan in 1917

- Timeline, with various portraits

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Kindler's New Literature Lexicon. Edition Munich 1988.

- ↑ Deutschlandradio, 2007 , accessed on March 22, 2012.

- ↑ a b Erhard Schütz: About happiness to forget God. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. September 11, 1984.

- ↑ Quoted from Winfried Menninghaus, afterword in the island edition by Hans im Glück. 1981, p. 817.

- ↑ See accusation by Knuth Becker

- ↑ Translated by Mathilde Mann, the 3rd edition published by Eugen Diederichs in Jena in 1909 and further editions there, including 1922; and more often. Here [ie Danish forms of name] after the following Danish scientific edition = Henrik Pontoppidan: Det forjættede land [The promised land]. Part 1 - 3 in 3 volumes (Part 1: Muld [Erde, Ackerboden; in the German translation with no title of its own]; Part 2: Det forjættede land ; Part 3: Dommens dag [The day of judgment]). Edited by Thorkild Skjerbæk. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1979, ISBN 87-01-72941-1 , ISBN 87-01-73951-4 and ISBN 87-01-73961-1 . (German edition can be read online via gutenberg.spiegel.de.)

- ↑ Hans im Glück 1981, epilogue, p. 862.

- ↑ Henner Reitmeier: The big stick out. A relaxicon. Oppo-Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-926880-20-8 , pp. 179/180.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pontoppidan, Henrik |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Danish writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 24, 1857 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fredericia |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 21, 1943 |

| Place of death | Copenhagen |