Good

The Bön ( Tibetan བོན ། Bon , German Truth, Reality, True Teaching) was the predominant religion of the Tibetans before Buddhism was established as the state religion in the 8th century . It is widespread in today's Tibet and other parts of Central Asia , China, as well as Nepal and Bhutan . The Bon is an animistic - polytheistic religion with strong shamanistic properties. Ancestral cult and a distinctive funeral and memorial culture are also important aspects of Bon.

Later Bon and Buddhism influenced each other (→ syncretism ) , whereby ritual and shamanistic elements or Bon deities came from Bon into Buddhism and, conversely, Buddhism significantly influenced Bon.

In 1977, the Bon was officially recognized by the Tibetan government in exile and the Dalai Lama as the fifth spiritual school of Tibetan Buddhism.

In 2006 the Yundrung-Bön Center Shenten Dargyé Ling in France was recognized by the state as a monastery of an independent religious community.

history

According to legend, the renewed Bon religion goes back to the mythical Tönpa (master) and Buddha Shenrab Miwoche from the country of Tagzig and is said to have replaced earlier animal sacrifices with symbolic offerings.

Later the Renewed Bon expanded and became the state religion in Zhang-Zhung, which surrounded the holy Mount Kailash . The Central Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo conquered the country in the 7th century (probably 634) and ended his dynasty with the killing of King Ligmincha (Ligmirya).

Under King Trisong Detsen (from 755) the Bon was increasingly ousted and persecuted by Buddhism. Under King Langdarma (reign 836-842) the situation of the Bonpa (followers of Bon) improved temporarily. After his murder, the Tibetan kingdom fell apart. As a result of further persecution, the Bönpa were pushed into the fringes of the Tibetan cultural area, such as Amdo in the northeast and Dolpo in Nepal.

With the beginning of the so-called "new translation tradition" (Sarma) of Buddhism in the 11th century, both the Buddhist Nyingma tradition and the Bon reorganized on the basis of found teaching texts (terma) from the time of persecution and confusion. A systematic teaching building was created and the ordination of monks and nuns spread.

In 1405 the Menri Monastery was founded by Bön-Lama Nyammed Sherab Gyeitshen. This and the later founded Yungdrung Ling Monastery became the main centers of Bon.

After the Chinese army marched in in the mid-20th century, both Bon and Buddhism were severely persecuted, especially during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–76). No Tibetan monastery survived the turmoil of that time unscathed. The Menri Bön Monastery was re-established in Dolanji while in exile in India .

In 1977 the Dalai Lama recognized Bon as the fifth spiritual school in Tibet . Since then, two representatives of Bon have belonged to the Tibetan parliament in exile, as do the other four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

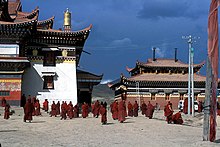

Today there are over 264 active Bon temples and monasteries in Tibet and China.

distribution

Apart from the rebuilt Menri Monastery in Dolanji in exile in India, the Bon is still alive in Tibet and Nepal. Bon is more widespread in Eastern Tibet; there are also isolated communities in Western and Central Tibet and among nomads. Since the 1980s, some Bon monasteries in Tibet have been rebuilt and settled by monks, says Yungdrung Ling. Furthermore, the religion of the Primi people in Yunnan is closely related to the Tibetan Bon.

to form

In the history of Bon there are three distinguishable forms that are still practiced. The oldest is a pre-Buddhist animistic-shamanistic religion, also called old Bon or black Bon . The second form is the Yungdrung-Bön, also called the Eternal or Auspicious Bön, which is said to go back to the Buddha Shenrab Wedwoche . The new Bon is based on retrieved texts ( Terma ).

Old Bon / Black Bon

The animistic origins date from pre-Buddhist times and contain shamanistic rituals and beliefs that are very different from the new Bon. The Gelugpa used Bon magicians (Nagspa) to ward off demons, and the practices of the Tibetan state oracle also come from the ancient tradition.

While later Bon forms took over the Buddhist ideas of karma and reincarnation , funeral rites were and are central in the old Bon, and there were complex accompanying rituals at the death of the king, a high-ranking nobleman or a minister in order to prepare them for a good life in the afterlife.

The Bon religion has its own pantheon of gods, spirits, demons and other beings. The ritual themes are magic, trance experiences , sacrifices to the gods, fortune telling , trips to the underworld , weather magic, media contact with spirits and the defense against demons.

The original Bon thus resembles other animistic religions such as Japanese Shinto , Altaic animism or Chinese shamanism .

Eternal Bön / Yungdrung-Bön

Yungdrung Bön ( Swastika -Bön), also called Eternal Bön , goes back to the mythical teacher and Buddha (Tönpa) Shenrab Miwoche . Historical representatives of the Yungdrung Bön tradition are the masters Tapihritsa and Drenpa Namkha .

The teachings of this school include more than 200 works. This also includes writings on philosophy, medicine, metaphysics and cosmology . The philosophical foundations are close to Buddhism, such as the teachings on karma (the law of cause and effect) and compassion. The deities of the old Bon were integrated as meditation deities ( yidam deities) or as protectors of teaching and vice versa, deities and demons of Bon were adopted by the Buddhist Nyingmapa .

The main teachings of Yungdrung-Bön are the "Nine Ways", other subdivisions call them "Four Gates and a Treasury" or the "Outer, Inner and Secret Instructions". The latter are sutra , tantra and dzogchen , similar to those of the Nyingma school. There is evidence that dzogchen, the teachings on "great perfection," existed in Zhang Zhung before Buddhism. In contrast, the Dzogchen teachings of the Nyingma go back to Garab Dorje from the land of Oddiyana.

The teachings also include the teachings of "Zhang Zhung Nyan Gyud", the "oral teachings of Zhang Zhung", the oldest traditions of a Dzogchen meditation system of the Bon.

Representatives of the Yungdrung-Bon who teach in the West are the venerable Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche and his disciple Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche .

New Bon

The new Bon, also called the Reformed Bon , systematically stands between Yungdrung-Bon and the Buddhist Nyingma tradition. It developed from a synthesis of teaching elements of the Yungdrung-Bön and elements of the Nyingma from the 14th century, mainly through the mutual finding of termas of the Bön and Nyingma traditions. A representative of the new Bön was Bönzhig Yungdrung Lingpa , also known as Nyingma- Tertön under the name Dorje Lingpa (1346–1405).

The rituals are similar to Buddhist ones, with the ritual circling in opposite directions. The invoked deities, iconographies , myths and mantras are specific to Bon. Also, the training of a Bon monk does not differ from that of a Buddhist monk, for example a Geshe degree can be acquired through the study of logic and philosophy and the goal of the practice, dzogchen, is not too different from the Buddhist dzogchen in which liturgy is used Padmasambhava called and the altar is often decorated with a picture of the Dalai Lama .

to teach

The teachings of Bon are based on extensive writings ( Kanjur and Tanjur ) which are structured differently. One of the subdivisions is the "nine ways" of the Bon, which roughly correspond to the nine vehicles of the Nyingma tradition. The principles of the doctrine are the same as in Buddhism, which goes back to Buddha Shakyamuni, who, according to Bon, was a disciple of Tönpa Shenrab Miwo in a previous life . Despite this proximity to Buddhism, the Bön also has its own teachings, rituals, myths and gods, so that it is considered an independent religion.

The nine ways of the Bon are divided as follows:

- Path of the priest of prophecy: fortune telling, astrology, ritualism and medicine.

- Path of the priest of the visual: Methods for pacifying the gods and demons of this world.

- Path of the priest of illusion: methods of domination of enemies.

- Path of the priest of existence: methods of salvation and questions about the period between death and rebirth.

- Way of the Virtuous Followers: Believers who act virtuously, strive for perfection, and build and venerate stupas .

- Way of the ascetics: ascetic disciplines, partly Buddhist, partly unbuddhist.

- Path of pure sound: practice of higher tantra, theories about transformation through mandalas.

- Path of the primeval priest: exercising the practice of mandalas through preparation, meditation and the realization of super-rational states of perfection.

- The highest accomplishment (Dzogchen)

Other classifications speak of four gates and a treasury or five treasuries.

The nine paths concern different groups of priests who performed different tasks. The literature of Bon goes back a long way and the division into categories of magic is a Buddhized form of literature. In older scriptures other categories are sometimes used, such as B. Himmelsbön or Funeral Bon, so that different groups of priests had probably already performed different tasks in the original Bon.

Meditation and dzogchen

Meditation systems are divided into three forms in the new Bon:

- The most important of the meditation systems is the Zhang Zhung Snyan grud, which is said to go back to a master from Zhang Zhung in the 8th century.

- A khrid is said to go back to a hermit in the early 11th century. This meditation is divided into periods lasting one to two weeks. Initially there were 80 periods, later only 15.

- At the beginning of the 11th century, texts were found that described dzogchen and dealt with the 'highest perfection'. These texts are similar to those of the Nyingma.

Practices

Shamans and priests , who mostly live outside the monasteries, soothe spirits with offerings, cast out demons or symbolically offer dough figures, ceremonial cakes, flour and butter. The Bonpa believe in magical practices and Shenrab Miwo himself passed them on. There are also mystery games with mask dances, chants and offerings. The dances are called sTag dmar 'Cham,' the dance of the red tiger demon 'and are often about the ancient mountain deities of Tibet. The Cham dances were adopted from Buddhism.

The Phurba cult was also adopted from Buddhism . Phurbus or Phurbas are magical daggers for banishing demons, for magic weather such as hail protection or for cleaning. The master Shenrab Miwo was always depicted with a large phurbu in hand. The Phurbu wizard was also feared for black magic. The curse of the wandering daggers z. B. should serve to destroy a victim over greater distances. For this purpose, the Phurbu is rolled in the hands, discussed with magical formulas and, with the help of the dagger god Phurpa, hurled to hit the victim telekinetsch .

Zor rituals use magical weapons, the Zor, to ward off bad influences. Zor are mostly small pyramids made of dough that are endowed with magical powers. If you hurl anger, it releases magical powers that are supposed to destroy the enemy or the calamity.

Crosshairs, Mdos, are made as ghost traps. They consist of threads that form geometric figures on crossed wooden sticks. Making crosshairs requires a complex ritual in which deities are invited to cover the crosshairs. Crosshairs are often placed over front doors to protect the home and its occupants. After a certain period of time, the crosshairs are usually burned with the demons trapped in them.

Amulets and talismans are also worn as jewelry, often made of coral and turquoise or in silver containers. These lucky charms, often several, are worn at all ages and all social classes.

Magic damage to be exerted by black Bönpa or Nagspa (wizards) against payment, for example, the horn is a Wildyaks ritual filled with a drawing of the victim and impure substances manifold, sealed with black thread and hidden of the victim in the foundation of habitation.

mythology

The diverse myths of the Bön deal with cosmogony , theogony and genealogy in various levels of complexity. Many narratives or tracts describe spells and implements in detail and often refer to various forms of exorcism and magic .

Recurring motifs are the distinction between the beneficial and the harmful, the pairing of deities or mythical beings and the division into good, bad and ambivalent deities. Sacred places such as grottos and mountains are also a recurring motif, the latter corresponding to the soul of the country or protective gods.

The most important mountain of the Bön is the Kailash (also Ti Se), soul of the country, seat of the heavenly gods, center of the world and is thought of as a huge chörten made of crystal or as a palace or as the seat of a palace of certain gods with four gates leading from Guardians of the cardinal points are guarded.

Tagzig Olmo Lungring is thought of as a pure land , beyond the impure existence in which all enlightened ones are reborn. It is indestructible and filled with eternal peace and joy. The Yungdrung-Bön has its origin here and Buddha Shenrab Miwo was born here.

In the creation myths of the New Bon one can also find Zurvanitic or Shivaitic influences. The origin is thought of as a state of empty possibility, from which the primordial egg arises which produces the world or the world is created by a primordial being.

The Bon pantheon

In the Bon religion every natural phenomenon is animated, so that there is an almost unmanageable abundance of spirits, gods, demons and mythical creatures. These beings live in places that are named in the cosmology of Bon. Some of them are particularly important for this religion and widespread nationwide.

The khyung bird

One of the main protective deities of Bon is the mythical bird Khyung. The powerful snake killer has a bull's head that is connected to the sun and storm clouds and is similar to the Indian Garuda . On the one hand, he is seen as the mount of the demonic dMu-king, on the other hand he accompanies the high world god Sangs po 'bum khri. West of the Kailash, a valley is dedicated to the Khyung, in which, according to myths, there was a silver castle. This silver lock appears as a holy place in most prayers and recitations of Bon.

Sangs po 'bum khri

The god Sangs po 'bum khri is a heavenly deity and is considered to be the ruler (Srid pa) of the present world age . One distinguishes five aspects of the Srid pa in this god: the body, speech, merit, works and spirit. The god is white and his throne is carried by a white khyung with green wings. He embodies mercy, redemption, and salvation.

Other names for this god are Lha chen sangs po dkar po, white pure great spirit, or Bum khri gyal po in western Tibet.

Palden Lhamo

Palden Lhamo is also called Srid (pa'i) rgyalmo in the Bön and is considered a protector, a great mother and a symbol of the rhythms of life and death.

Pehar

Pehar or Pekar is an oracle deity that is also worshiped by Buddhists. In addition to the oracle function, he has many other tasks, dignities and duties as a protector of teaching, religious guardian, annihilator of enemies, friend of the saints and as guardian god over Zhang Zhung. According to Buddhist legend, he is said to have been forced by Padmasambhava to protect Buddhism.

Lha, bTsan, gNyan

In the mythology of Bon there are not only the individual gods but also very many different groups of spirit beings that can be benign or malignant. Some should be mentioned here:

Lha are benign heavenly beings. In every region of heaven there are different groups and they embody the divine power with which people are connected. Some Lha do not live in heavenly regions, but are e.g. B. the god of the hearth or the god of inside or outside. The Tibetan capital Lhasa (place of the Lha) is named after the Lha, and the king was considered the grandson of the Lha.

bTsan are particularly powerful and still play a role in Buddhism. They live between heaven and earth, but also inhabit forests, rocks, glaciers and gorges. The king of the bTsan wears armor, a banner and a noose. The bTsan appear as wild red hunters on red horses. They are considered to be the rulers of the innumerable gNyan. According to myths, bTsan can cause heart attacks and deadly diseases.

The gNyan symbolize the center and can be found in the sun, moon, stars, clouds, rainbows, wind and rocks, for example. The gNyan are also associated with the cardinal points. The ruler of the gNyan wears armor with turquoise ornaments, a victory banner with a goose on it and has a crystal-colored face.

literature

- Bru-sgom rGyal-ba g.yung-drung: The Stages of A-Khrid Meditation. Dzogchen Practice of the Bon Tradition. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala 1996, ISBN 81-86470-03-4 .

- Christoph Baumer: Bön - The living ancient religion of Tibet . Academic Printing and Publishing Company, Graz 1999, ISBN 3-201-01723-X .

- Andreas Gruschke: The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces. Kham . Vol. 1: The TAR Part of Kham (Tibet Autonomous Region) . White Lotus Press, Bangkok 2004, ISBN 3-89155-313-7 , pp. 80-84.

- Marietta Kind: The Bon Landscape of Dolpo. Pilgrimages, Monasteries, Biographies and the Emergence of Bon. Bern 2012, ISBN 978-3-0343-0690-4 .

- Namkhai Norbu: Dzogchen-The Way of Light. Diederichs, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-424-01462-1 .

- Namkhai Norbu : Drung, Deu and Bön. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala 1995, ISBN 81-85102-93-7 .

- Tenzin Wangyal: The Short Path to Enlightenment. Dzogchen meditations according to the Bon teachings of Tibet. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-596-13233-9 .

- Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: Night Practice. Meditations in sleep and dream. Diederichs. Hugendubel, Kreuzlingen 2001, ISBN 3-7205-2189-3 .

- Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: The Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep. Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, NY 1998. (English edition of Exercise of the Night ), ISBN 1-55939-101-4 .

- Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: The Healing Power of Buddhism. Diederichs. Hugendubel, Kreuzlingen 2004, ISBN 3-7205-2487-6 .

- Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen, Lopon Tenzin Namdak: Heart Drops of Dharmakaya. Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, NY 1993, ISBN 1-55939-172-3 .

- Lopön Tenzin Namdak , Karin Gungal: The healing Garuda. A piece of Bön tradition Garuda Verlag, Dietikon 1998, ISBN 3-906139-09-3 .

- John Myrdhin Reynolds (Vajranatha): The Oral Tradition From Zhang-Zhung. Vajra Publications, Kathmandu 2005, ISBN 99946-644-4-1 ( vajranatha.com only available from American booksellers)

- Lopön Tenzin Namdak, John Myrdhin Reynolds: Bonpo Dzogchen Teachings. Vajra Publications, Kathmandu 2006, ISBN 99946-720-5-3 ( vajranatha.com only available from American booksellers)

- Michael A. Nicolazzi: Secret Tibet. The primal religion of Bon. Patmos, 2003, ISBN 978-3-491-69400-2 .

- Per Kvaerne : Bon . In: Mircea Eliade (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Religion. Volume 2. Macmillan Library Reference, New York 1987, pp. 277-281. ISBN 0-02-909710-X .

- Keith Dowman: Secret, Sacred Tibet. A Guide to the Mysteries of the Forbidden Land. Kreuzlingen, Munich 2000

- Gerhardt W. Schuster: The old Tibet. Secrets and mysteries. St.Pölten (among others); NP-Buchverlag 2000 ISBN 3-85326-137-X

- Sebastian Schüler: From Syncretism to Padmaism: On the relationship between religion and politics in early Tibetan Buddhism under Padma Sambhava Journal of Religious Culture, No. 137, 2010 http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/irenik/relkultur137.pdf

- Giuseppe Tucci , Walther Heissig : The religions of Tibet and Mongolia. Stuttgart [u. a.], Kohlhammer 1970

Canon catalogs

- Per Kvaerne: The canon of the Tibetan Bonpos . In: Indo-Iranian Journal No. 16, 1974, pp. 18-56, 96-144.

- Chandra Lokesh et al. a .: Catalog of the Bon-Po Kanjur and Tanjur. In: Indo-Asian Studies No. 2, 1965; New Delhi.

Web links

- Bon and Tibetan Buddhism Transcript of a lecture by Alexander Berzin

- Bön bibliography also in German (himalayanart.org) (PDF; 97 kB)

- Ligmincha Germany (student of Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche in Germany)

- Vajranatha - translator of Bön texts together with Lopön Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche (English)

- Cataloging Canonical Texts of the Tibetan Bon Religion (PDF; 115 kB)

- Bön and early Buddhism in Tibet (PDF; 180 kB)

- Conference of the University of London 2011 on "Bon, Shangshung, and Early Tibet" (English)

- Exhibition Museum für Völkerkunde, Vienna PDF

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sam Van Schaik: Tibet: A History . Yale University Press, 2011, p. 99 ff.

- ↑ Samten Karmay: The Treasury of Sayings: a History of Tibetan Bon . OUP, London 1972 [London Oriental Series, volume 26]. (Reprint by Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi 2001)

- ↑ 研究 . In: archive.is . September 14, 2012 ( archive.is [accessed November 20, 2018]).