Epic of Gilgamesh

The Gilgamesh epic is the content of a group of literary works, which comes mainly from the Babylonian area and contains one of the oldest surviving poems that have been written down. The Gilgamesh Epic in its various versions is the best known work of the Akkadian and Sumerian literature .

As an overall composition it bears the from the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. BC occupied the title "He who saw the deep" (ša naqba īmuru). A presumably older version of the epic was known under the title “He who surpassed all other kings” (Šūtur eli šarrī) since the ancient Babylonian period (1800 to 1595 BC).

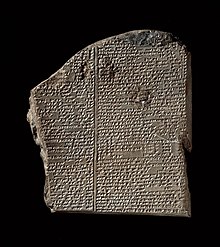

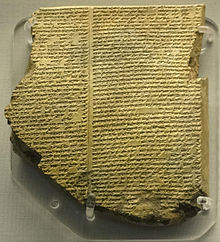

The most comprehensive surviving version, the so-called twelve- table epic of Sîn-leqe-unnīnī , is preserved on eleven clay tablets from the library of the Assyrian king Aššurbanipal . A twelfth panel with an excerpt from the independent poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld was appended to the epic. Of the once more than 3000 verses of the epic, not quite two thirds are known from different lines of tradition.

The epic tells the story of Gilgamesh , a king of Uruk , his exploits and adventures, his friendship with Enkidu , his death and Gilgamesh's search for immortality. In the end, the hero has to realize that immortality is only given to the gods, but life and death are part of human nature . Rainer Maria Rilke called it the "epic of the fear of death".

The existing written material allows the original version to be backdated to at least the 18th century BC. BC, but probably reaches into the writing time of the Etana myth in the 24th century BC. BC back. The epic was brought into line with the historical conditions of the time in ever new adjustments and editors. For centuries it was basic school reading in the Middle East and was itself translated into Hittite and Hurrian . The Roman Aelian , who wrote around 200 AD, mentions Gilgamesh, called Gilgamos by him, as the mythical king of the Babylonians.

Rediscovery

The first clay tablets with fragments of the Gilgamesh epic were found by Hormuzd Rassam in 1853 . George Smith (1840–1876) translated it in 1872 and is therefore considered the real rediscoverer of the Gilgamesh epic. Smith translated the fragment which dealt with the inundation of the earth and which is very similar to the account of the Flood in the Book of Genesis ( Gen 7.10–24 EU and Gen 8.1–14 EU ) of the Bible . This fragment is part of the eleventh and final tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh. This strengthened the hypothesis that the Bible had adopted this text in a modified form. In 1997, the Assyriologist and Judaist Theodore Kwasman identified the missing first two lines of the epic in the British Museum .

translation

The text of the epic had to be reconstructed from various fragments, with larger gaps ( lacunae ) remaining. Since the various fragments were written in different languages ( Old Babylonian Akkadian , Hurrian and Hittite ), there were translation and assignment difficulties. Some text passages were not preserved and had to be reconstructed. Often the meaning of important terms was not known.

It was not until SN Kramer , Sumerologist from Philadelphia (USA), put large parts of the Sumerian mythical poems into a meaningful context. The first complete German translation was made by Alfred Jeremias in 1891. In 1934 the epic was translated again by Albert Schott . Schott has standardized the personal names of the epic, so that the name Gilgamesh also prevailed for the older stories, which in the original use the name d GIŠ-gím-maš . The same applies to the name pairs Ḫuwawa / Ḫumbaba and Sursun-abu / Ur-šanabi .

With a new scientific edition, the London ancient orientalist Andrew R. George put the text-critical research of the Gilgamesh epic on a new basis. From more than 100 text finds that had since been newly translated, a new evaluation of the traditional text resulted. In addition, five further fragments were translated between 2003 and 2005. In 2005, the Assyriologist Stefan Maul presented a comprehensively revised, new, poetic translation that contains additions, personal interpretations and extensions to the older translations of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Versions of the fabric

Sumerian narrative wreaths

The oldest literary adaptations of the Gilgamesh material come from the Sumerian cities in Mesopotamia . From this early period there are some clay tablets in Sumerian cuneiform with fragments of several texts:

-

Cycle around Gilgamesh , the hero is called "Bilgameš" or "Bilga" for short.

- Gilgamesh and Agga von Kiš , this text does not appear in the twelve-table epic. He reports on the transfer of power from Kiš to the city of Uruk .

- Gilgamesh and the young women .

- Gilgamesh and Ḫuwawa , there are two to three versions of this text, which were the starting point for panels 4 and 5 of the twelve-panel epic.

- Gilgamesh and the heavenly bull , almost the entire text was taken up in the 6th panel of the twelve-table epic. It is about a dispute between Inanna and Gilgamesh.

- Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld , this text is only used as a suggestion in the early versions of the epic. The second half of it is added as an appendix late. In some fragments Gilgamesh is presented as a judge in the underworld. It contains a vision of the underworld and legitimizes Gilgamesh as the founder of the cult of the dead.

- Death of Gilgamesh , this text was later applied mainly to Enkidu.

- The Sumerian version of the Flood tale does not belong to the stories about Gilgamesh. The figure of Uta-napišti is called Ziusudra here . This text is probably a retrospective translation into the Sumerian language, which itself draws from several older versions and, in the form of the Atraḫasis epic, represents an independent mythical report.

Versions in Babylonian language

Old Babylonian

So far only small fragments have become known. It is becoming apparent that even before the first dynasty of Babylonia or the Isin-Larsa period, a first epic was created from the Sumerian material about Gilgamesh, which was later expanded and varied several times. In ancient Babylonian times, the hero is written with the sign "Giš", although it is probably pronounced "Gil".

In terms of content, the pieces can be assigned to different passages and thus arranged in a sequence:

- From the first panel of the Old Babylonian epic only the opening line and a short fragment are preserved, which tells of the creation of Enkidus.

- A fragment of the second panel, now in Pennsylvania, probably comes from Uruk or Larsa; According to one comment, it is the second part of a series. She tells of the arrival of Enkidus with his wife in Uruk, where Gilgamesh wants to make use of his ius primae noctis and Enkidu prevents him from doing so. After a fight between the two, Gilgamesh takes Enkidu on as a follower.

- Fragments of the third panel exist in Yale, in the Schoyen Collection and among the finds from Nippur and Tell Harmal . They report that Gilgamesh wants to cut down cedar wood, which Enkidu warns of with reference to Ḫuwawa, whom he knows from earlier.

- A possible find of the fourth panel has not yet been published.

- A fragment of the fifth tablet is in Baghdad and tells of the killing of Ḫuwawa by Gilgamesh and Enkidu, which opens the way to the Anunnaki . The felled cedar trunks both flow across the Euphrates to Uruk.

- Two fragments of the seventh panel, in the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Berlin and London, can be put together and may come from Sippar . They tell of Gilgamesh's mourning for the deceased Enkidu and his search for Uta-na'ištim.

- Another table, the so-called master table, tells of Gilgamesh's arrival in the afterlife with the innkeeper Siduri . It also contains the famous speech of the Siduri , which is not included in the twelve- table epic.

It is unclear whether further tablets belong to this old Babylonian version of the epic. Findings of further fragments indicate that two or more different versions of this text may exist.

In addition to the deluge hero Uta-na'ištim, there is the older Atraḫasis epic in Old Babylonian about the deluge, which is outside the Gilgamesh tradition.

Middle Babylonian

Under the Kassite dynasty , the epic spread to Hattuša and Megiddo . It was translated into Hittite via Hurrian . So far, no uniform epic can be reconstructed.

- Hattuša

- Middle Babylonian fragments were found there, which tell of the arrival of Enkidus in Uruk and the train to the cedar forest. There are also traces of the adventure with the heavenly bull. The fragments break off with a dream of Enkidus of an assembly of gods. In addition to these Middle Babylonian fragments, there was a Hittite retelling, which was probably not made directly, but via a Hurrian version, of which a trace has also been found here.

- Ugarit : Piece of a new prologue and fragment from the fight with Ḫuwawa.

- Megiddo and Ur

- Fragments referring to the death of Enkidus (dream of the underworld and curses). These pieces are new and show the development from the Sumerian “Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld” to the Neo-Babylonian version.

New Babylonian

The twelve-table epic was ascribed to a scribe by the name Sîn-leqe-unnīnī, who was the "secretary" of Gilgamesh. In Assyriological research, this is mostly understood as the final editor who, for the final composition of the text, resorted to older, almost identical works and was only published in the 12th century BC at the earliest. BC - both assumptions cannot be proven, however. The final version of the epic with about 3600 lines of verse was probably written down on eleven tablets in Uruk. The majority of the work is preserved through clay tablet fragments from the library of Assurbanipal (669 BC - 627 BC) in Nineveh , to which a twelfth tablet was attached, which is a verbatim translation of "Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld" contains.

The Hittite version

The Hittite version of the epic has only survived in very fragments (a few dozen fragments of plates), although the number of duplicates shows that the work must have been very well known. Two Akkadian versions have also been found in the capital, Hattuša, and some Hurrian fragments also have textual references.

Compared to the Mesopotamian versions of the epic, the Hittite version is significantly simplified and lacks many details and a whole series of secondary characters. The Hittite version consists of three plates, but the text is incoherent in many places because too little of the plates has survived.

The epic

According to Sumerian tradition, Gilgamesh was king of the Sumerian city of Uruk; one third human and two thirds divine. His name means the ancestor was a hero or the descendant is a hero . The epic tells depending on the version of his hero did with that of the goddess Aruru created humanoids Enkidu (which often appears as a friend, but sometimes even as a servant in the texts), but focuses mainly his search for immortality .

A number of other ancient oriental works show striking similarities to the Gilgamesh story. This also includes interesting parallels in the later biblical tradition. The figure of the biblical Noah is strongly reminiscent of the divinely chosen hero Utnapishtim . In Genesis Chapter 6 EU there is also the motif of the sons of God who materialized on earth and entered into relationships with human women. The children thus conceived are called “ Nephilim ” and are described as a kind of “demigod” who are known for their superhuman strength and their quick-tempered and bad temper.

Correspondences can also be found in the Greek heaven of gods with its titans and demigods, especially in the human children of Zeus , whom, according to the legends of the gods, Zeus is said to have fathered with mortal women as he pleased.

The content of the twelve-table epic

Panel I.

Gilgamesh, the hero of the story, is two thirds God and one third man. He has extraordinary physical powers, is portrayed as a fearless and uncouth man of action and rules as king in Uruk. His work is the huge city wall on which a stele announces his deeds. His despotic style of government and the oppressive burdens associated with his building projects in particular lead to anger among the women of Uruk, who complain to the goddess Ištar . In order to tame the ruler, the mother goddess Aruru creates Enkidu from clay according to the order of the sky god An , father of Ištar , who initially lives as a wild, human-like being in the steppe near Uruk with the animals of the wilderness. Gilgamesh learns of Enkidu through two dreams. Gilgamesh's mother Ninsun , who interprets dreams and knows the future, points out to Gilgamesh the imminent arrival of Enkidu in Uruk, who will later become his brother. Gilgamesh is delighted with Ninsun's news and impatiently awaits Enkidu's arrival.

A trapper discovers Enkidu, who protects the wild animals and protects the herd from the trapper's deadly facilities. His father advises him to go to Uruk and ask Gilgamesh to send the prostitute Shamḫat , who is supposed to alienate his flock by sexually seducing Enkidu. Gilgamesh repeats the words of the father of the trapper with regard to Šamḫat, who, knowing that the gods had originally commissioned him to lead Enkidu to Uruk as an opponent of Gilgamesh, goes with the hunter into the steppe. When Enkidu discovers Šamḫat, he succumbs to her seduction skills. After the following one-week lovemaking, as predicted by the trapper's father, Enkidus herd flees into the vastness of the steppe and leaves him alone. Šamḫat is able to convince Enkidu to go to Uruk with her.

Plate II

During a stopover in a shepherd's camp near Uruk, Enkidu gets to know human food and beer. Before that, he had grown intellect in the presence of Shamḫat. Enkidu finally transforms himself into a human being through the work of a barber . Once in Uruk, Enkidu and Gilgamesh meet. The subsequent fight ends in a draw. Tired of the argument, the two heroes sink down and become friends. Gilgamesh and Enkidu decide to perform a heroic deed together and kill Ḫumbaba , the guardian of the cedar forest, in order to fell cedars in Ištar's forest.

Plate III

Gilgamesh's mother Ninsun asks the sun god Šamaš for help in view of the imminent dangers and declares Enkidu to be her son through adoption . In addition, she provides Enkidu on the neck with her divine symbol as a protective symbol.

Plate IV

Now as brothers, Gilgamesh and Enkidu set off on their way. They are on the road for five days, digging a well in the evening and every evening Gilgamesh asks for a dream from which he awakens in horror every time. Enkidu interprets his dreams and calms Gilgamesh in this way. Finally, Šamaš announces that Ḫumbaba is outside his protective forest.

Plate V

Gilgamesh and Enkidu find Ḫumbaba, and after a terrible and dangerous fight, they overcome him with the help of Šamaš. Ḫumbaba, held in place by the thirteen winds of the sun god, begs for his life, but because he offended Enkidu, he is finally killed, and shortly before his end he curses Enkidu. They made a door for the Temple of Enlil from felled cedar .

Plate VI

When Ištar sees the returning hero Gilgamesh, she falls in love with him. But Gilgamesh rejects them. Angry about this, she goes to Anu , the father of the gods, and demands that the heavenly bull be sent to kill Gilgamesh. Once in Uruk, the monster wreaked havoc. The bull kills hundreds of Uruk's men until Enkidu and Gilgamesh take up the fight and kill him. Gilgamesh brags, calls himself the mightiest of all heroes and mocks Ištar. The following night, Enkidu is startled from a dream.

Plate VII

He dreams that the assembled gods agree that the two have now gone too far. They decide to punish them both by killing Enkidu and letting Gilgamesh live. Enkidu falls ill. With his fate in mind, he curses the cedar door that he made for Enlil, he curses the trapper and the prostitute Šamḫat, because of whom he gave up the wilderness. When Šamaš points out that without this turn he would never have met Gilgamesh and would have made him a friend, he forgives them. On the first night of his agony, he dreams of a demon who will drag him off into the underworld to Ereškigal , whom Enkidu calls Irkalla by her Akkadian nickname . Enkidu asks Gilgamesh for help in a dream, but Gilgamesh refuses it out of fear. After twelve days, Enkidu dies.

Plate VIII

Gilgamesh mourns his friend and laments his loss. He commissioned a statue of Enkidus, laid out his friend and looked for the gifts for the gods of the underworld, which were listed individually. Finally he has the river dammed up for the construction of the grave, in the middle of which the friend is to be buried.

Plate IX

The death of Enkidu makes Gilgamesh aware of his own mortality, a prospect that drives him into fear and despair. So he goes on a long journey to find the secret of life in a foreign country. He doesn't want to die like Enkidu, and hopes that his immortal ancestor Uta-napišti can help him. In search of this famous sage, he first wanders through the vastness of the steppe and finally comes to the far east to Mount Mašu. There is the gate to the "path of the sun / of the sun god" - in modern research sometimes viewed as a tunnel, since absolute darkness prevails over most of it. Two beings, half human, half scorpion, guard the entrance of the path and ask Gilgamesh about his desire. He explains to them that he wants to ask Uta-napišti about life and death. They answer that no one has succeeded in doing this yet, but give access to the twelve “ double hours ” long path. After eleven “double hours” on the way in absolute darkness, twilight sets in, after twelve “double hours” it is light again and the hero arrives in a garden full of precious stone trees.

Plate X

He meets the divine Siduri , who runs a tavern here on the nearby sea of the other world. Although she is afraid of Gilgamesh's emaciated, gloomy sight, she tells him - out of pity - that Utnapištim lives with his wife on an island, surrounded by the water of death , which protects the immortals from uninvited guests. Only Ur-šanabi , the ferryman Uta-napištis, knows the means of crossing this obstacle unscathed. When Gilgamesh arrives at Ur-šanabi and his ferrymen, the stone people who usually take care of the crossing , the stone people refuse to help; he smashes it and asks the ferryman to take him to the island. He explains that it was the stone people who manufactured and operated the pegs , without whom the crossing would be impossible; therefore the king himself now has the task of taking on both tasks. He has to cut 300 cedars and make as many picks from the trunks. After departure, the ferryman instructs Gilgamesh to leave each of the poles used in the sea floor behind him so as not to come into contact with the deadly water. When the last bar ran out, they hadn't reached the island yet. Gilgamesh takes off Ur-Sanabi's dress and hangs it like a sail between his arms. This is how they reach Uta-napišti, to whom Gilgamesh presents his concerns and reports on his mourning for Enkidu. Uta-napišti explains to Gilgamesh that the gods determine the fate, assign death and life, but do not reveal the day of death.

Plate XI

Gilgamesh asks Uta-napišti why he, who is like him in everything, is immortal. Uta-napišti then reveals a secret and tells the story of a flood disaster . A completely preserved version of the plate is not available. Therefore, the plot had to be reconstructed from Sumerian, Babylonian, Akkadian, Hurrian and Hittite tradition fragments. Accordingly, Gilgamesh seeks out his ancestor, who is called Ziusudra in the Sumerian version of the story and tells him the story of the flood (framework plot).

According to this story, the god Enki warned Ziusudra of a flood that would destroy all life and advised him to build a ship. The situation is made more complicated by the fact that Enki had to swear to the other gods beforehand that he would keep silent about the coming catastrophe. In order not to break his oath , Enki uses a ruse and does not speak directly to the person, but speaks his words against the reed wall of the house in which Ziusudra sleeps. Ziusudra is warned of the danger in the form of a dream while sleeping. He then follows Enki's received orders from the dream, tears down his house and builds a boat from the material. At Enki's express instruction, he does not tell the other people about the impending doom. Ziusudra now lets the animals of the steppe, his wife and his entire clan board the boat . The Babylonian version reports on the course of the catastrophe, which breaks in the form of a flood over the country and lets it sink. After the water has run off, Ziusudra and his wife are rewarded by Enlil for saving living beings by the fact that both are deified and allowed to lead a divine life on the island of the gods "Land of the Blessed". In the Gilgamesh epic, Šuruppak in lower Mesopotamia is given as the place from which the flood began.

Now the frame story starts again. After listening to the story, Uta-napišti asks Gilgamesh to conquer sleep as the little brother of death for six days and seven nights, but Gilgamesh falls asleep. During his sleep, the Utanapistis put a piece of bread by his bed every day so that he could recognize his failure. After waking up and realizing his failure, Uta-napišti at least explains to him where the plant of eternal youth is. Gilgamesh digs a hole and dives into the underground freshwater ocean called Abzu . He quickly finds the plant and loosens his diving weights. When he emerges, the tide throws him to the land of this world where Ur-šanabi is waiting for him. You are on your way back home. Gilgamesh first wants to test the effect of the plant on an old man there. When he stops at a well, however, he is careless and a snake can steal the plant of eternal youth from him, whereupon it sheds its skin. He returns to Uruk sad and dejected, enriched by the knowledge that he can only acquire an immortal name as a good king through great works. When he arrived in Uruk, he asked Ur-šanabi to climb and marvel at the city wall of Uruk, which was already mentioned on panel I.

Modern reception

Unlike many Greco-Roman myths of Gilgamesh fabric was late, ie after about the second third of the 20th century, for music (as operas , oratorios (in particular) and literature Fantasy novels) as subject discovered.

literature

In his tetralogy Joseph and his brothers (from 1933), Thomas Mann , following the biblical research of his time, which among other things looked for templates for biblical motifs, interwoven elements of Gilgamesh mythology into the Joseph legend. Hans Henny Jahnn's cycle of novels River Without Banks (from 1949) is based in essential motifs on the Gilgamesh epic.

1984 and 1989, the US published science fiction -author Robert Silverberg the fantasy duology Gilgamesh the King (Eng. King Gilgamesh ) and To the Land of the Living (dt. The land of the living ), in the Gilgamesh and Enkidu in the Underworld continue to live together, split up and, with the help of Albert Schweitzer , come together again. In the second part, The Land of the Living , Silverberg spins the Gilgamesh story based on the River World Cycle by Philip José Farmer by allowing Gilgamesh to be "resurrected" in a realm of the dead that differs only slightly from today's world. All the dead of our world, from all ages of history, are gathered there. Gilgamesh not only meets Plato, Lenin, Albert Schweitzer, Picasso and many others - but also his friend Enkidu, only to lose him again shortly afterwards.

Modern interpretations of the myth also include the 1988 novel Gilgamesch, König von Uruk by Thomas RP Mielke , which tells another variant of the epic, Stephan Grundy's novel Gilgamesch from 1998 and the 2001 drama Gilgamesh by Raoul Schrott , although the latter is by was rated very negatively by experts.

Gilgamesh: A Verse Play (Wesleyan Poetry) by Yusef Komunyakaa was also released in 2006 .

music

The Gilgamesh epic has been set to music several times. In 1957 the oratorio Gilgamesch by Alfred Uhl was premiered in the Wiener Musikverein , in 1958 in Basel The Epic of Gilgamesh by Bohuslav Martinů (composed in winter 1954/55). The 1964 opera Gılgamış by Nevit Kodallı , in Turkish, as well as Gılgameş (1962–1983), composed by Ahmed Adnan Saygun . From 1998 there is a dance oratorio based on the Gilgamesh epic with the title The Order of the Earth by Stefan Heucke . The opera Gilgamesh (composed 1996-1998) by Volker David Kirchner was premiered in 2000 at the Lower Saxony State Opera in Hanover. In 2002 Wilfried Hiller created a vocal work based on the Gilgamesh epic entitled Gilgamesh for baritone and instruments.

Visual arts

In the visual arts, the painter Willi Baumeister in 1943 and, in the 1960s, the graphic artist Carlo Schellemann gave the Gilgamesh epic a visual shape in their respective series of pictures.

Comics & Graphic Novel

The figure of Gilgamesh was also adopted from 1977 (for the first time in The Eternals # 13) as Gilgamesh (alias Forgotten One or Hero ) in the Marvel comics , in which he appears for centuries under different names and is one of the Eternals - these are god-like creatures ; he is also briefly a member of the Avengers . Parallels between the two characters exist insofar as they are both godlike, of even superhuman physical strength and extremely large, although the comic figure from hands and eyes can give off cosmic energy and fly and the mythical Gilgamesh is a powerful and accomplished ruler who whose fear of death has to overcome.

In 2010, the 358-page interpretation of the Gilgamesh epic was published as a graphic novel illustrated by the artist Burkhard Pfister .

TV

In the episode Darmok of the Star Trek series Spaceship Enterprise: The Next Century (1987–1994), Captain Picard tells a dying alien parts of the Gilgamesh epic.

In the American Dad episode 90 ° North, 0 ° West (Season 12, Episode 7), Santa Claus tries to bring Ḫumbaba to life.

Video games

Gilgamesh gained notoriety in the video game scene through various appearances in the Japanese computer role-playing game series Final Fantasy , which has been appearing since 1987 , as an opponent or a helping hand. Depicted as a powerful armored warrior and sword collector, he has, among other things, the power to summon Enkidu from the underworld.

He is also one of the central characters in the visual novel Fate / Stay Night. Here he is portrayed as an almighty king with unlimited treasures, who can access his seemingly infinite number of riches at any time and thus becomes one of the most powerful beings of all. He is also a playable character in the mobile game Fate / Grand Order .

See also

- Ishtar Gate

- Nimuš (Mount Nimuš)

literature

Text editions:

- Andrew R. George: The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic. Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. 2 vols., Oxford University Press, London 2003, ISBN 0-19-814922-0 .

Translations:

- Stefan Maul : The Gilgamesh Epic. (newly translated and come, 6th revised edition) Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-52870-5 .

- Wolfgang Röllig : The Gilgamesh Epic. Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-010702-7 .

- Raoul Schrott , Robert Rollinger , Manfred Schretter: Gilgamesh: Epos. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-534-15935-7 .

- Hartmut Schmökel : The Gilgamesh Epic. (rhythmically transferred). 9th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-17-015417-6 .

- Wolfram von Soden (translator), Hajo Edelhausen (illustrator): Gilgamesch or the walls of Uruk - images of the incarnation. Preface by Rolf Wedewer and Karl Hecker. Edition Orient, 1995, ISBN 3-922825-60-5 .

- Wolfram von Soden, Albert Schott (Assyriologist) : The Gilgamesh epic. Reclam, Stuttgart 1982, reprint 1997, ISBN 3-15-007235-2 .

Secondary literature:

- Gary Beckman: The Hittite Gilgamesh. In: BR Foster (ed.): The Epic of Gilgamesh. A New Translation, Analogues, Criticism. New York / London 2001, ISBN 0-393-97516-9 , pp. 157-165.

- Jürgen Joachimsthaler : The reception of the Gilgamesh epic in German-language literature . In Sascha Feuchert u. a. (Ed.): Literature and history. Festschrift for Erwin Leibfried. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55566-8 .

- Meik Gerhards: Conditio humana. Studies on the Epic of Gilgamesh and on texts of the biblical prehistory using the example of Gen 2-3 and 11, 1-9. (Scientific monographs on the Old and New Testament 137). Neukirchen-Vluyn 2013, ISBN 978-3-7887-2707-9 . (Interpretation of the Epic of Gilgamesh, pp. 105–188)

- Walther Sallaberger : The Gilgamesh Epic. Myth, work and tradition. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56243-3 .

Web links

Online editions and articles

- Anette Zgoll: Gilgamesh. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Gilgamesh. Epic and explanations

- Wibi-Lex: Epic of Gilgamesh as a template for the Bible

- The review of the graphic novel on the Gilgamesh epic

Videos

Dubbing

- Attempts to reconstruct the spoken Akkadian . Also the recorded Gilgamesh epic in different versions with transcription. Website of the School of Oriental and African Studies , University of London

Remarks

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke in a letter dated December 31, 1916 to Helene von Nostitz ; see Rainer Maria Rilke, Helene von Nostitz: Correspondence. Edited by Oswalt von Nostitz. Insel, Frankfurt 1976, p. 99.

- ↑ Claus Wilcke: About the divine nature of royalty and its origin in heaven. In: Franz-Reiner Erkens: The sacredness of rule - legitimization of rule in the change of times and spaces: Fifteen interdisciplinary contributions to a worldwide and epoch-spanning phenomenon . Akademie, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003660-5 , p. 67.

- ↑ Aelian: De natura animalium 12.24.

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/first-lines-of-oldest-epic-poem-found-1185270.html

- ↑ a b Walther Sallaberger: The Gilgamesh epic. Myth, work and tradition . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ a b c d e Wolfram von Soden, Albert Schott: The Gilgamesch epic. Reclam, Stuttgart 1982, pp. 115-120, cf. also Walther Sallaberger: The Gilgamesh epic. Myth, work and tradition . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2008, pp. 61-67.

- ↑ Published in Dina Katz: Gilgamesh and Akka . Styx Publ, Groningen 1993, as well as in AOAT 253, p. 457 ff.

- ↑ So far unpublished

- ↑ Published in Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 80, pp. 165 ff .; Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 81. S. 165 ff .; Texts from the environment of the Old Testament 3.3. P. 540 ff.

- ↑ Published in Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 87. P. 97 ff.

- ↑ Published in Aaron Shaffer: Sumerian sources of tablet XII of the epic of Gilgamesh . University of Pennsylvania, 1963.

- ↑ Published in Antoine Cavigneaux, Farouk Rawi u. a .: Gilgamesh et la mort . Styx Publ, Groningen 2000.

- ^ Wolfram von Soden, Albert Schott: The Gilgamesch epic. Reclam, Stuttgart 1982 Schott-Soden (1982), pp. 120-122.

- ↑ a b c d e Walther Sallaberger: The Gilgamesh epic. Myth, work and tradition . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2008, pp. 80-82.

- ↑ a b c Wolfram von Soden, Albert Schott: The Gilgamesch epic . Reclam, Stuttgart 1982, pp. 6-8 and pp. 26-32; see. also Walther Sallaberger: The Gilgamesh epic. Myth, work and tradition . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2008, pp. 80-82.

- ↑ This can be ruled out, since Semitic names such as Sîn-leqe-unnīnī came into use much later

- ↑ Cf. 1. Book of Mose ( Genesis ) chapters 6–9 and 11th panel Gilgamesh epic .

- ↑ a b Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. Pp. 49-50; Walther Sallaberger: The Gilgamesh Epic. P. 10.

- ↑ The trapper referred to here represents the type of non-fighting animal catcher, an activity that was viewed negatively in the steppe landscapes of Mesopotamia; according to Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 157.

- ↑ The Mesopotamian terms whore, courtesan and joy girl represent the names of the temple servants of Ištars, which refer to their normal commercial activities outside the temple and are not based on the actual temple activity. They also belong to the cult staff of the respective temples and represent the sexual libido of the goddess Ištar; according to Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 158.

- ↑ The trapper's father speaking to his son: “Go, my son, with you take Shamḫat, the prostitute […] When the flock arrives at the watering place, she should remove her clothes and show her charms […] becomes a stranger to him his flock (then), in the midst of which he grew up. [The son reacts:] He paid attention to his father's advice, the trapper went away, he set off on the journey ”; according to Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 51.

- ↑ The divine mandate that Enkidu should put an end to Gilgamesh's deeds in Uruk is expressed in Shamḫat's later speech to Enkidu; according to Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 158.

- ↑ Walther Sallaberger: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 11.

- ↑ Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 158.

- ↑ The barber shaves and oils Enkidu, who has "become so much of a person"; according to Stefan Maul: The Gilgamesh epic. P. 59.

- ↑ The description of the end of the world refers to blazing fire, subsequent storms and subsequent tidal waves that are reminiscent of a storm surge or a tsunami . Rainfalls, which according to the Bible narration were responsible for the flood, are not reported. Excerpt from the 11th panel, based on the translation by St. Maul ( The Gilgamesh Epos. 5th edition. CH Beck Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-52870-5 , p. 143 f.): “Hardly that the dawn began to glow, a black cloud rose from the foundation of the sky. From deep within her Adad roared incessantly, and Schullat and Hanisch precede him, the 'throne-bearers' walk along over mountain and country. Errakal tears out the stakes, Ninurta goes along. He let the weirs overflow. The underworld gods raised torches, and with their blaze of fire they set the land ablaze. […] The first day the storm rolled down the country. He raced along furiously. But then the east wind brought the flood. The force of the flood passed over the people like a slaughter. The brother cannot see his brother, nor do people recognize one another in annihilation. Even the gods were afraid of the flood! They fell back, they rose up into the sky of Anum. [...] 'Like fish in a school they (people) fill the sea (now)!' […] For six days and seven nights, wind and weather, storm and deluge go by roaring along. But when the seventh day dawned the storm began to lighten, the flood came to an end. ""

- ↑ The flood story is in the new and expanded translation by Stefan Maul ( Das Gilgamesch-Epos. 5th edition. CH Beck Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-52870-5 ) and is the basis in this form the act described here. Texts from other table fragments found in the meantime have also been incorporated into this new translation, which now allow a more precise reconstruction of the Gilgamesh story; Archaeological finds from this region confirm that there were several major floods of the Euphrates and Tigris in ancient times . A previously suspected connection between these historical floods and the legendary Flood can be viewed from the point of view of today's science, but cannot be confirmed.

- ↑ a b For example by Stefan Maul: R. Schrott, Gilgamesh. Epos. With a scientific appendix by Robert Rollinger and Manfred Schretter, Munich 2001 , in: S. Löffler u. a. (Ed.), Literatures 1/2 2002, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ “The Man of Sorrows from Uruk - The Gilgamesh Epos as a Dance Oratorio in Gelsenkirchen”, in: Opernwelt , 42,3 (2001) pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Roland Mörchen: "Spiegel des Musikleben - Volker David Kirchner's Gilgamesch in Hanover - new version of Wilfried Hiller's Schulamit premiered in Hildesheim", in: Das Orchester , 48,9 (2000), pp. 45-46.

- ^ Alan Cowsill: MARVEL Avengers Lexicon of Superheroes . ISBN 978-3-8310-2759-0 , pp. 66 (232 p., English: MARVEL Avengers The Ultimate Characters Guide . Translated by Lino Wirag, Stefan Mesch).