Gehinnom

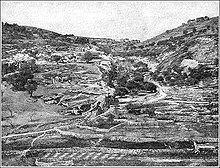

The Hebrew name Ge-Hinnom , more rarely also Ge-Ben-Hinnom ( גֵּי־הִנֹּם or גֵּי בֶן הִנֹּם Gej [Ven] Hinnom , German 'Schlucht [of the son] Hinnom's' ) is a toponym in biblical Judah , which is partly translated in the Greek translation of the Old Testament ( Septuagint ), partly in the Graecized form Gehenna (γαιεννα) or similar (γαιβενενομ , γαι-βαναι-εννομ) was reproduced. An important necropolis has been located in the valley since the time of King Hezekiah (8th century BC) , as excavations since 1927 have shown. Today this place is called "Wadi er-Rababi".

Usage in the Old Testament

In the area of the gorge was the border between the tribes of Judah and Benjamin , between the Refaim valley and Ejn-Rogel. Gehinnom is mentioned for the first time in the book of Joshua as a deep, narrow gorge at the foot of the walls of Jerusalem ( Jos 15.8 EU ). The gorge is located in the south of the old city of Jerusalem . It extends from the foot of Mount Zion in an easterly direction to the Kidron Valley . During the time of the kings , child sacrifices were offered to Moloch in Gehinnom and Tofet . The prophet Jeremias condemned this cult several times and foretold that for this reason Tofet and Gehinnom would be called "Murder Valley" ( Jer 19,6 EU ).

In Isa 66,24 EU there is the prophecy that one will go out to look (at an unspecified place) the corpses of those who have apostated from God. These bodies that remain unburied - apparently rebellious members of the people of Israel - are called "disgust", and the statement that was later taken up in the Gospel of Mark ( Mk 9.43, 45, 47 EU ) and only there expressly related to the Gehenna is made that “their worms do not die and their fire does not go out” ( Mk 9.48 EU ).

Change of meaning

In the Hellenistic era, the name of the gorge was transferred in prophetic texts to a realm of the dead that was thought to be a place of punishment. This change in meaning is not documented in all of its steps in the sources, but the process can be roughly reconstructed. According to a hypothesis by Lloyd R. Bailey, the starting point was a cult site of the chthonic (ruling in the depths of the earth) deity Moloch in the Hinnom Valley. According to a widespread custom, altars were erected as far as possible in places that were suitable as contact points to the kingdom of the god in question because, in the opinion of the faithful, they were located near this kingdom or even formed its entrance gate. The place of worship in the Hinnom Valley, where the blood of the sacrificed people and animals was conducted to earth, was therefore, in the imagination of the sacrificers, the entrance to an underground realm of the dead. This is why it got its name from the place where its entrance was.

The eschatological connotation of the valley as a place of future punishment for the deceased is linked to Jeremiah 7.30–8.3, where the Moloch cult in the Hinnom valley is mentioned as the reason for a future punishment (the conquest of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II ). This text was written after the catastrophe of the conquest. Its author puts the prophecy in Jeremiah's mouth, with which he intends to interpret experienced calamities as punishment. Through this fictitious back-dating, the valley, previously only known as the scene of past crimes, becomes the site of a future punishment for the first time. The formulations chosen announce the disaster to be expected in such a way that it could be interpreted at any later point in time as an announcement of impending punishments. The open formulation made it possible for the readers to push their expectation of judgment further and further into the distance and finally to the end of the story. This process of eschatologizing took place in the Apocrypha of the Old Testament. In the apocryphal Book of Enoch of Ethiopia (3rd / 2nd century BC) the Hinnom Valley is not mentioned by name, but is obviously meant in the descriptions of a future place of punishment after the judgment of God. There is talk of an abyss filled with fire (1 Enoch 90:26). In the 4th book of Ezra and in the Sibylline oracles (around 100 AD), Gehenna is expressly referred to as the place for the future punishment of evildoers. According to God's judgment, the punishment should take place after a bodily resurrection.

In rabbinical literature there are two ideas about Gehenna as a place of godly punishment. One assumes a resurrection of the dead and a subsequent judgment; the evildoers are sent to the Gehenna in retribution for their sins, which is materially understood. According to the other concept, Gehenna is a spiritual hell for the souls who receive their cleansing punishments there immediately after the death of the person. In rabbinical literature, punishment is regarded as temporary for some of those affected and perpetual for others. The latter are called "children of Gehenna" in the Talmud . The idea that the stay in Gehenna usually lasts one year led to the custom in Judaism that the kaddish prayer was said daily by the bereaved during the first year after the death of their loved one, so that their lingering there was made easier even though many rabbis rejected this as a superstition. The worst part of Gehenna, in the Babylonian Talmud, is Tzoah Rotachat, where Balaam , Jesus and Titus would be tormented (the first two with boiling sperm or excrement). In his treatise on Chapter 10 (Perek Helek) of the Sanhedrin Mixed Nativity, Maimonides states that the narratives relating to Gehenna in rabbinical literature are pedagogically motivated inventions that help humanity, who is still considered immature, to keep the commandments of the Torah should stop. In fact, according to the Jewish religion, there is no Gehenna in the form of a hell, but only an annihilation of the soul as the worst punishment for the unjust.

According to the Talmud, there is a hole in the ground between two palm trees in the Hinnom Valley, from which smoke rises; this hole is known as the "entrance to the Gehinnoma". This idea is attributed to Rabbi Jochanan ben Sakkai (died around 80 AD).

New Testament

In the Greek text of the New Testament, the word appears in the form “Gehenna” ( γέεννα ), which is based on the Aramaic gêhinnam , with the omission of the final -m , as it was sometimes done in the Septuagint through the transcription γαιεννα (Jos 18:16 Uncials B) and is also known from the development of the name Mirjam to Μαρια "Maria".

The word appears in eleven places in the Gospels in the New Testament (seven times in Matthew , three times in Mark , once in Luke ) in the reproduction of sayings of Jesus and once in the letter of James.

In the sayings of Jesus it is traditionally translated as “hell” and as a real or metaphorical scene of punishment for body and soul ( Mt 10.28 EU ); ( Lk 12.5 EU ) interpreted. Gehenna is the place where “the worm does not die and the fire does not go out” ( Mk 9.44 EU ). Among those who will not attain the kingdom of heaven but succumb to the judgment of Gehenna ( Mt 23.33 EU ), those are named who call their brother a “fool” ( Mt 5.22 EU ), as well as especially the hypocritical ones Scribe and Pharisee (Mt 23:29). The one who follows them in turning away from the kingdom of heaven is referred to with the formula already known from the Talmud as "son of Gehenna", "who is twice as bad as you (ie the scribes and Pharisees)" ( Mt 23.15 EU ).

In the epistle of James, the Gehenna appears in connection with the metaphorical idea of the power of the tongue, which, "set on fire" by the Gehenna ( Jak 3,6 EU ), for its part work through sinful speech like the cause of a forest fire and "the wheel of Life on fire ”.

The Talmud researcher Chaim Milikowsky points out differences between two ideas of Gehenna in the New Testament. One concept is based on the presentation in Matthew's Gospel , the other on that in Luke's Gospel . In Matthew, Gehenna appears as a place of punishment after the end of the world that affects body and soul at the same time; Luke already thought of punishing the soul immediately after death. Accordingly, the two different concepts known from rabbinical literature can also be found in the New Testament. With this Milikowsky turns against the view of the New Testament scholar Joachim Jeremias . For the New Testament, Jeremias adopts a consistently consistent use of language with a sharp separation of Gehenna and Hades ( Hades as the place of residence between death and the future general resurrection, Gehenna as the eternal place of residence of those condemned in the Last Judgment ). Milikowsky advocates the assumption that Hades and Gehenna are used as synonyms in the New Testament .

Koran

The Arabic equivalent in the Quran is Jahannam .

Facilities in the valley

The central valley is crossed by the country road to Hebron, on which there is a Sabil Suleyman the Magnificent from 1536 (restored in 1978). The Merrill Hassenfeld Amphitheater on the floor of the Sultan's pond , which falls dry in summer, is more recent . In the northern valley there is the Teddy Park (named after the long-time mayor Teddy Kollek ) and the Töpfergasse, a row of shops with workshops and craftsmen's shops.

literature

- Lloyd R. Bailey: Gehenna. The Topography of Hell. In: Biblical Archaeologist. 49 (1986) pp. 187-191.

- Immanuel Benzinger : Gehennom . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VII, 1, Stuttgart 1910, Col. 931.

- Klaus Bieberstein : The Gate of Gehenna. The emergence of the eschatological memory landscape of Jerusalem. In: Bernd Janowski u. a. (Ed.): The biblical worldview and its ancient oriental contexts. (Research on the Old Testament; 32). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2001, pp. 503-539, ISBN 3-16-147540-2 .

- Chaim Milikowsky: Which Gehenna? Retribution and Eschatology in the Synoptic Gospels and in Early Jewish Texts. In: New Testament Studies. 34 (1988) pp. 238-249.

Web links

- Klaus Bieberstein: Hinnomtal. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

Remarks

- ↑ In Jos 18:16 νάπη ονναμ occurs next to γαιεννα, these two forms appear only here in the OT.

- ↑ For the topography and the function of the valley as a necropolis as well as for the course of the excavations see Bieberstein (2001) pp. 511-514.

- ^ John L. McKenzie: Second Isaiah , New York 1968, p. 208.

- ↑ On Moloch as a chthonic deity see Bieberstein 2001, pp. 516-518 ( reading sample in the Google book search).

- ↑ Bailey 1986, pp. 189-191.

- ↑ On the individual steps of the new connection of the Hinnomtal in the post-exilic literature, see Bieberstein (2001) pp. 518–525; see. Milikowsky pp. 238-241.

- ↑ Milikowsky (1988) p. 239; see. Duane F. Watson: Article Gehenna , in: The Anchor Bible Dictionary , ed. David Noel Freedman, Vol. 2, New York 1992, pp. 926-928, here: 927.

- ↑ Milikowsky (1988) pp. 239-241, Watson (1992) p. 928.

- ↑ Jordan Lee Wagner: The Synagogue Survival Kit: A Guide to Understanding Jewish Religious Services, Lanham 2013, p. 184.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer : Jesus im Talmud, 2nd edition, Tübingen 2010, p. 181.

- ↑ Maimonides' Introduction to Perek Helek, ed. u. trans. v. Maimonides Heritage Center, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Maimonides' Introduction to Perek Helek, ed. u. trans. v. Maimonides Heritage Center, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ On this tradition, see Max Küchler : Jerusalem , Göttingen 2007, pp. 756f. (with receipts, also for the medieval reception of the performance).

- ↑ Hans-Peter Rüger: Art. Aramaic II. In the New Testament , in: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. III, 2000, pp. 602–610, p. 605 § 1.14

- ↑ Milikowsky (1988) p. 238.

- ↑ Blue Letter Bible. "Dictionary and Word Search for geenna (Strong's 1067). (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 29, 2012 ; Retrieved on September 29, 2008 (English). Information: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Milikowsky (1988) pp. 242-244; agreeing with Watson (1992) p. 927.

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias: Article γέεννα , in: Theological Dictionary for the New Testament , Stuttgart 1933 (reprint Stuttgart 1957), pp. 655f.

Coordinates: 31 ° 46 ′ 9 ″ N , 35 ° 13 ′ 41 ″ E