Anthropology of religion

The subject of religious anthropology is a subdivision of religious studies founded by Julien Ries and others in the late 1980s . It deals in particular with basic religious phenomena such as the sacred , belief , myth , transcendence , rites or symbols as well as with the related cognitive and unconscious processes and their anthropogenetic emergence and formation under different cultural framework conditions.

Delimitations

The system of religious studies is complex, and in the course of time different sub-areas have often developed from other sciences, each with different starting points, which deal with different aspects of religion or examine the same aspects from different perspectives:

- The sociology of religion , as it was founded by Max Weber at the beginning of the 20th century as a branch of sociology, in contrast to anthropology of religion, deals less with the role of religion in the individual in its anthropological and historical development. Rather, her research subjects are predominantly social groups and societies and their formative relationships to religion. The direction of observation is thus opposite to that of religious anthropology (society → individual, not individual → society).

- The cultural anthropology also is the sociology , but above all of Ethnology and Folklore close. From the comparative consideration of all empirically ascertainable possibilities of human cultural formation, it draws back on the human being as a being able to culturally. It thus goes far beyond the area of religion, although it also examines this as a central cultural achievement as a phenomenon, but in universal contexts such as with Leo Frobenius , Bertrand Russell or Oswald Spengler or in the context of special questions such as with Samuel P. Huntington .

- On the other hand, there are numerous points of contact with the phenomenology of religion , insofar as it deals with individual basic phenomena of the religious and their relationships to one another, i.e. questions such as the sacred and religious imaginative worlds such as belief in God, primeval times, end times or the afterlife, whereby in religious anthropology, however, the human being examines in his spiritual The focus of the considerations is development and not the phenomenon as such.

- Similarly, the relationship designed to psychology of religion , however, dealt with the anthropological aspect in its temporal development was not (as the archetype ) and on the current state concentrated to give especially with the practical means of psychology and depth psychology worked will, for example, when examining the problem of conscience .

- The history of religion, in turn, focuses on the external and internal processes of the historical developments of religions, on specific phenomena and forms that also occur morphologically , as well as on economic, political and social framework conditions that can be or were observed in each case.

- Accordingly, studied anthropology of religion manifestations of religion at different peoples of the younger and new history and is accordingly a branch of anthropology. She is particularly interested in the religions of the writeless peoples, whereby the means of ethnological field research are used above all .

- The philosophy of religion after all, is a sub-discipline of philosophy and attempted a philosophical penetration of the phenomenon of religion, although religion and philosophy are often difficult to separate, especially in ancient cultures and those interpretations are particularly influenced by the time-varying laws of hermeneutics, such as those of hermeneutical Circles circumscribes.

- Religious anthropology , on the other hand, must not be confused with theological anthropology , which interprets people in the context of Christian doctrine and their likeness to God and is closely linked to Christology .

Origin and subject of research

The co-founder is Julien Ries , who with the ten-volume series “Treatise on the Anthropology of the Sacred”, published from 1989 onwards, together with over 50 scholars from all over the world, was decisive for the development of the subject in its modern form has contributed. In the anthropology of religion, the history of religion, history, cultural history, prehistory and paleoanthropology, ethnology and sociology are closely linked. The focus of interest is on the phenomenon of the sacred and the anthropology of Homo religiosus, as well as the role that the development of human consciousness played , especially in the discovery of transcendence . The myth and symbol of the so-called Homo symbolicus , rites and structures of religious behavior are also essential topics in this context. In contrast to the thematically similar phenomenology of religion , anthropology of religion does not deal so much with the abstract phenomena of Edmund Husserl , but with very concrete human processes, in particular with the earliest findings such as paleoanthropology , archeology and the results of psychology and depth psychology , and here in particular with the results of consciousness research . Correspondingly, Sigmund Freud (for example in “ Totem and Tabu ”) and CG Jung (for example in his theory of archetypes ) were also important forerunners with their research on the psychology of religion , as was Mircea Eliade with his research on religion and ethnology . Julien Ries notes in "The Origin of Religions":

“The hermeneutic approach leads the historian to an encounter with the author of these facts ( note: religious phenomena in their function as carriers of meaning ), that is, the person himself. This means that hermeneutics calls for the intervention of religious anthropology. Indeed, this has the task of dealing with the human being in his capacity as creator and user of all sacred symbolism. The recently developed anthropology of religion belongs to the anthropology of the symbolic systems with which the work of CG Jung, Henry Corbin , Georges Dumézil , Mircea Eliade, André Leroi-Gourhan and Georges Durand dealt "

Definition and main research areas

In close connection with the history of religion , especially with regard to its earliest and early phases, with the sociology of religion and the psychology of religion , the anthropology of religion describes the conditions of religious experience in the believing individual as well as the interactions between this, society and religious community . In the 10-volume treatise on the “anthropology of the sacred”, edited by Julien Ries, some of the themes are paradigmatically present: 1. Origins and representation of Homo religiosus, 2. Indo-European man and the sacred, 3. Mediterranean cultures and the sacred , 4. The religious believer in the Jewish, Muslim and Christian religions, 5. Crisis, ruptures and changes, 6. Native cultures in Central and South America, 7. The cultures and religions of Native Americans, 8. Japan. The great religions of the Far East, 9. China. The Great Religions of the Far East, 10. Metamorphoses of the Holy.

Ries defines as follows:

“The anthropology of religion examines the human being in his capacity as creator and user of the symbolic totality of the sacred insofar as it expresses religious convictions that determine his life and behavior. Parallel to the special religious anthropology that deals with each individual religion (Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, Christianity), an anthropology is developing that deals with Homo religiosus and its behavior during the experience of the sacred. "

Overall, religious anthropologists in their own and in foreign societies primarily examine the phenomena and aspects and their development that are briefly described below on the basis of the most important interpretations of Julien Ries and others.

Everyday religiosity and structures of religious behavior

The everyday religiosity describes in all religions the practical manifestations of daily religious practice altogether, so prayers, sacrifices, rituals etc., and shows close relations with the Customs . Here in particular there are strong overlaps with the other sub-disciplines of religious studies, but also with folklore, ethnology and psychology in general, especially since the subject of research here is relatively unspecific and broad. There is also contact with church political problems (compare the interview with the Jewish religious anthropologist Richard Sosis).

The basic structures of religious behavior , however, form the basis of all everyday religiosity and are therefore an important subject of research in religious anthropology. From a religious anthropological perspective , there are three main aspects:

- The complex of image, symbol and creativity: The space for symbolic experiences opens up through images that come from objects in the outside world, for example sky, sun, stars, animals, plants, mountains, etc. According to Eliade, the symbol does not work with objects, but with pictures. These images, in turn, act on the awareness and enable archetypes ( archetypes ), so primordial patterns in individual and collective unconscious exist as apparently innate standardized neural which pattern evolutionarily developed in connection with the development of cognitive skills and similar to other properties of the people as favorable factors were anchored in the genome . If these archetypically anchored symbols are addressed, they in turn activate psychic forces from the unconscious, and the consciousness begins to search for the correspondences and roots that correlate with the archetypes. Creativity arises through this dynamic from the unity of the archetype, which expands from its center.

- Imagination: This means the entirety of the images and their relationships that arose in this way in Homo sapiens. It is characterized by an ordering dynamism that looks for systematics on the basis of the original unit and within the framework of the existing and retroactive environmental conditions. An incessant exchange develops between the two levels: that of subjective appropriation and that of objective suggestions and demands that come from the cosmic and real environment. Thus, two factors are always at work in the human soul: the soul itself and its mechanisms, which absorb and interpret the image of the object, and the reactions of the objective environment which influence the soul.

- The third main factor, according to Ries, is initiation : it only grants access to the religious heritage that has developed over thousands of years and has been preserved in the collective memory. Initiation is a revelation that leads to sharing in this inheritance and its wisdom. It includes myths, symbols, rites, beliefs, ideas and conceptions, scriptures, temples and sanctuaries, and is both religious and cultural heritage. The initiation tradition with its social, cultural and religious structures is indispensable for Homo religiosus, because it enables him to experience new sacred experiences. Accordingly, initiations are present in all religions worldwide and form a central part of the ritual inventory, especially as rites of passage such as birth, circumcision or baptism, manhood, at burials, marriages, etc.

Origin and effects of religious symbolism

There are several definitions of the term symbol . Examples: 1. A concrete sign that through a natural relationship evokes something absent or something else that cannot be perceived. (André Lalande); 2. The symbol is an image that lets a secret meaning emerge, it is the epiphany of a mystery. (Georges Durand); 3. The visible representation of something invisible. (Natale Spineto); 4. A specific type of sign which associatively reveals its meaning .; 5. Symbolism describes the symbolic content of a representation, or a meaning represented by symbols.

From an anthropological point of view, symbols have three main functions:

- A biological one: images emanating from objects and actions introduce a unity in consciousness, which in turn leads to a creative dynamic. All cultural achievements are based on it. The world speaks to man through the symbol and reveals the otherwise unrecognizable modalities of the real.

- The symbol has an important function in the human soul, because it creates a connection between the conscious and the unconscious and gives the consciousness the power to guide the unconscious and to penetrate to the root of the archetypes , i.e. the universally valid images according to CG Jung.

- The symbol also gives the consciousness the means to establish a connection to the “superconscious” , which means the discovery of transcendence for humans and identifies them as Homo religiosus.

Since every symbol contains three elements, the invisible, the medium that communicates its appearance and the sacred, it also plays a central role in hierophany. Through the mediator (stone, tree, animal, human, etc.) as a visible part, the appearance of the invisible takes place, the revelation of the sacred. According to Eliade, the structure and function of symbols are fundamental to the experience of the sacred.

However, symbolic signs can only be deciphered if they are either sufficiently clear or if one knows the religious background to which they refer. André Leroi-Gourhan made this speculative and controversial attempt for the symbols of Franco-Cantabrian cave art , where he divided them into male and female. If the knowledge of this background is missing, however, the most important finding is that these symbols are even present and thus allow conclusions to be drawn about the general function of the human mind and soul of that time.

Belief systems, myths and mythograms

The myth is “a story about events which concern the origins and in which the intrusion of the sacred into this world is described. The task of history is to provide people with models for leading their own lives. As a bearer of meaning, the myth represents patterns of thought and action that allow people to find their way around the world. It is a sacred and exemplary story for the life of people and peoples. "Myths have a symbolic structure, and there are three religious-anthropological aspects:

- With their help, humans interpret the relationships between the current time and the time of the beginnings, which are usually represented as the golden age .

- The restoration of this Golden Age, or the longing for it, is the basis of human ritual efforts to restore a connection to it.

- Through its messages, the myth determines people's behavior in everyday life by imitating role models, which in turn are based on archetypes. Agricultural myths, for example, gave life to nature and vegetation at the New Year celebrations and were the origin of fertility.

The mythogram (Ries) is “a system of representation that is characteristic of the Upper Palaeolithic and that conveys a message without a narrative style. The message needed a key, that is, the narration of a myth whose elements we have lost. The mythograms represent the essence of the structure of the Franco-Cantabrian cave paintings ”, in which they first appear more and more. Mythograms are thus signs of existing myths that refer to existing belief systems.

Belief systems always contain such myths and related mythograms, in medieval Christianity iconographically for example the lily as a symbol of the virginity of Mary and thus the mythogram of the biblical story of the Annunciation . The systematization of a belief, i.e. the linkage of myths that is ultimately also relevant for power politics, is, however, typical of more developed cultures and high cultures and, by nature, the subject of the sociology of religion. The hierophany and epiphany lead here in the Theophany .

Establishment and functioning of rituals and institutions

The rite (ritual and rite are largely used synonymously in religious studies) stands at the intersection of human beings, culture, society and religion and is an action that the mind has thought up, the will decided and the body carried out with the help of words and gestures. It has its place in the context of a totality of hierophany and is related to the indirect experience of the supernatural. He tries to establish a connection with a reality that extends beyond this directly tangible world. The ritual act is always tied to a symbol structure, with the help of which the person manages the transition from the carrier of meaning to the meaning, from sign to being. There are three basic meanings:

- On the basis of archetypal prototypes, as conceived by CG Jung, ritual expresses the basic facts of life with the help of a symbolic language. According to Mircea Eliade , however, one can also speak of an “original model” without recourse to the collective unconscious, as it was already manifested in the first religions of the Middle East. In doing so, a real fact, an object, etc. is sacralized by resorting to the heavenly model . Every earthly phenomenon corresponds to a heavenly reality. Dimensions of buildings and temples, regional names, action processes, etc. are thus given cosmic references.

- The second archetypal component manifests itself in the symbolism of the center: cosmic mountain, middle of the earth, sacred space, world tree, river of the underworld.

- The third component is the divine example that man must imitate. Fertility rites are an example of this, they cause growth and prosperity by observing the sacred rites.

Through the rituals people had an experience of the sacred in relation to the divine world. There is an essential difference between magical and religious rituals to be observed: Magic is dominated by the desire for control with the help of certain cosmic forces, while religion turns to transcendence. Religious rites are effective in the context of hierophany, while magical rites call for help from forces that have no relation to the sacred (compare also shamanism ).

Function of religious rites: They are part of a symbolic expression through which the person seeks contact with the transcendent reality. The rite consists of technology and symbolism. The technique consists of gestures, actions, verbal utterances, etc .; its task is to open a path into ontological reality, from the bearer of meaning to being.

Development history:

- The first rites are in the Middle Paleolithic as burial rites of the Neanderthals in Qafzeh, or at least likely.

- In the Upper Paleolithic, they can be identified primarily in the Franco-Cantabrian cave art . Footprints are interpreted as remnants of initiation rites, as are hand negatives and hand positives on the walls, but also rare representations of humans and animals that are variously interpreted as shamans.

- In the Neolithic Age , the first adorers can be found in Valcamonica with arms stretched out in prayer. The same can be found among the Sumerians. Since the 3rd millennium, the Mesopotamian and Egyptian high cultures show numerous evidence of consecration rites.

- Finally, in the great religions there is a variety of rites. At the same time as the first temples, places of worship and altars, regulated sacrifices can be proven, as a sign of maintaining a privileged relationship between man and gods.

In the wake of this ritualization of religious life, the first institutions emerged .

- Preconditions and beginnings: In addition to the ability to create more complex abstractions, the primary prerequisite for the development of Homo religiosus is above all the ability to speak spoken, as can be proven paleoanthropologically for Homo erectus 400,000 years ago at the latest (shape of the bony palate , hyoid bone , Cranial skull discharges), the mechanisms of which, however, have not yet been clarified. Institutional forms of organization, which were initially of a purely social nature (family group, horde), could only develop through linguistic means to the flexibility and complexity that are indispensable for the emergence of religious thought systems and the resulting institutions. However, they did not yet lead to the formation of even rudimentary religious institutions, at most to socially determined group dynamic processes that go beyond the purely sociobiological of the animal-human transition field and of prehistoric and early humans , but provide the structural prerequisites for later demonstrable religious developments .

- The first evidence of the existence of actual systems and institutions can only be derived with certainty from the early Neolithic cave art, which was only possible in connection with a differentiating society with supraregional importance, which also already functioned in a division of labor and specialized, had a rudimentary education system and more Rites, such as hunting and initiation ceremonies, and thus presumably also myths, as the traditional cave art confirms with relatively great certainty. The structure of this earliest verifiable religiosity was probably shamanic .

- In the Neolithic there are finally very early evidence, the simpler the existence of religious institutions point out, as the examples of Gobekli Tepe and later of Çatalhöyük and Jericho show. Here the rites have multiplied so many times and have been given such a rich symbolic content that it can be concluded that religious behavior is becoming increasingly professional and institutionalized. The emergence of the megalithic culture in Europe and the Middle East, which can only be achieved through enormous collective efforts and which requires institutionalized religious and political leadership, points in this direction.

Transcendental Phenomena

The anthropology of religion deals intensively with the search for the origin of transcendence, which here is not to be understood in a philosophical abstract way , as in the case of Plato , in Scholasticism, or in Immanuel Kant and Heidegger , but in an anthropological-cognitive way. In addition to its potential origin, the handling of phenomena such as symbols, sacred things, myths, etc., which go along with it and are of interest from a religious and anthropological perspective, is examined.

Transcendence in this sense is the cognitive ability to transcend the realms of being and experience. It has its origin in the ontological division of the world into two ( dualism ), which evidently inevitably arose when a distinction had to be made between what was understood and what was not understood when looking at the world. In the process, a “logical-ontological area developed cognitively and real, which did not draw its validity from the sensual world of experience, is therefore transcendent towards it, but on the other hand has a meaningful relationship to it and is at the same time immanent , being for it and recognizable from it or can be experienced without being from her ”.

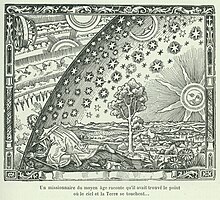

The tool production of the earliest humans ( Homo habilis , Homo erectus ) already required this ability to convert a certain abstract goal into the form and thus the effect of a certain tool, i.e. to imagine how it would / should work. This requires the ability to create symbols. According to Ries, this ability was soon transferred to the poorly understood or poorly understood phenomena of the environment, i.e. sky, stars, moon, sun, weather, but also growing and dying. However, early humans did not discover this central ability in an intellectual way, but through the play of their imagination and then gradually perfected it. Myths, which represent complex systems of symbols, probably didn't play a role at that time. They can only be proven as a possibility in the Upper Palaeolithic and its rock art and appear initially as a symbolism of the sky dome, which enabled early man to experience the sacred for the first time. According to Eliade, simply looking at the vault of heaven brought about an experience of the sacred in the consciousness of archaic man, since the height represents a dimension inaccessible to man and the stars thereby acquired the nimbus of the inaccessible, transcendent, something that was inaccessible, but immensely powerful.

Research here has four main sources:

- The study of the unscriptural peoples by ethnologists and anthropologists, who produced evidence of a very ancient symbolism of the sky dome with astral myths . The terms for heaven and God are often identical among these peoples.

- Neolithic rock engravings and paintings provide ample material, for example through the depiction of praying people (adorants).

- The now rapidly increasing rites of the Neolithic: burial rites are now pronounced and indicate the belief in life after death. Fire rituals and other rites prove religiosity and the awareness of transcendence.

- The study of the first great religions in Egypt and Mesopotamia, later also of the Indo-European peoples. With them, too, the symbolism of the sky dome is of paramount importance. The day and night skies have a religious function.

The Holy

The main subjects of religious anthropological research are the origin, constitution and delimitation of the sacred from the profane. The sacred manifests itself in myths, sounds, rites such as initiations, sacrifices , prayer or celebrations, people and natural objects, phenomena (such as fire, lightning) and processes (seasons, etc.) as well as natural and artificial places (temples, shrines, etc.) and pictures. Its main representatives are priests and rulers. It extends to all areas of life.

Two terms and concepts are important here:

- The sacred or sacred or numinous: it is the human ability to grasp the divine. The etymology of “sacral” with the root * sak- leads via the Latin verb sancire to the meaning “to give validity, to give reality, to make something real”. This means the basic structure of things and living beings. It is a metaphysical and theological term at the same time , the religious and cultural coloring of which is specific to the various peoples. It manifests as a power that is very different from the order of nature. The universal experience of the sacred thus implies the discovery of an absolute reality that man perceives as transcendent. Its terminology was only created by the people of high cultures, but it is certainly much older as a phenomenon and is at the beginning of the inner experience of religion. According to Rudolf Otto, the knowledge of the sacred proceeds in four emotionally determined stages:

- The feeling of being a creature.

- The horror of it (tremendum) .

- The feeling of mystery.

- The fascination of discovery ( fascinans) .

The forms in which the sacred manifests itself are secondary ideograms and merely reactions to the actual, meta-empirical sacred.

- The hierophany as a manifestation of the sacred: The term was coined in 1949 by Mircea Eliade, who represents a different interpretation here than Otto, and he calls it "the appearance of the sacred in the profane". The sacred appears in the world of phenomena and can be directly perceived by humans. It is the central element in the world of religion. Four factors play a role:

- The object or being by means of which the sacred manifests itself.

- The invisible reality that transcends this world.

- The “completely different”, “divine”, “ numinous ”.

- The central mediating element, i.e. the essence or object that contains the new dimension of the sacred. With humans it can be a priest, prophet, shaman or seer, etc. If it is a thing, say a sacred tree, it remains a tree, but Homo religiosus' relationship to it has changed. Whether the sacred occurs universally as a category is disputed. Above all, its manifestation in the Eastern religions creates problems here if one interprets the sacred as an absolute quality and not as a special manifestation of religious consciousness.

However, the concept of the sacred is not clearly defined. There are several variants:

- Otto's definition is based on Christian-Jewish premises and transcendental-philosophical approaches.

- On the other hand, German phenomenology of religion evaluates the category of the sacred as not actually definable and as an "experience-like encounter of man with sacred reality" ( Gustav Mensching ).

- Mircea Eliade then, in continuation of the romantic theology of revelation and with reference to Otto, represented the view of the continuous revelation of the sacred ( hierophany ).

- The empirically oriented religious studies, in turn, is based on the observation that cultures classify different things or facts as sacred at different times.

- Émile Durkheim has the dualism sacred vs. Declared profane to the basic structure of religion, a dichotomy that also includes pairs of terms such as pure / impure or the Polynesian mana- taboo complex and which the sociology of religion then took up.

- However, cultural anthropology was able to prove that this oppositional pairing is not sufficient for the explanation of religions and that the respective culture-specific context must also be taken into account.

- In this context, Ken Wilber refers to the human ability to transcend the ego, which is known above all from the mystically shaped Eastern religions, but also from Western mystics, whereby a higher state of consciousness is reached, which also the intensive perception of the sacred, even its absorption in it includes.

- Finally, modern neurotheology and neurophilosophy tries to localize God and thus the sacred in certain higher brain regions, without, however, answering the question of how it got there.

Theophany and institutionalization of religion

Theophany is seen here as a cultural and historical process, although it is often claimed by the monotheistic religions alone. It is a crucial link in the institutionalization of religions, because wherever a god is "looked at", specialists gradually emerge who claim a special institutional role for themselves, which is gradually secured by economic and social privileges.

The following processes can be seen:

-

Theophany : At the end of NATOufia , on the eve of the development of agriculture, there is the “birth of the gods”, and animal myths are evidently gradually transformed into agricultural myths or replaced by them. The French Cantabrian cave art , judging by the rock art, was an animal art , depictions of humans are very rare, both as cave paintings and as sculptures.

The finds in southern Anatolia, for example, in Göbekli Tepe and Nevali Cori , where sanctuaries and occasional burials can be identified, but there is no clear evidence of anthropomorphic statues of gods (unless the so-called T-pillars are interpreted in this way) may represent a transitional situation when some researchers consider the existence of ideas of gods for those very early Neolithic phases to be possible. Cults can also be suspected for reasons of population dynamics , but cannot be proven with certainty.

From the 8th millennium BC Then there are female figures in Mesopotamia , who now appear everywhere and are becoming more and more common, so that some researchers (e.g. Marija Gimbutas ) have already drawn the conclusion that it is not just a cult of Neolithic goddesses, but the portrayal of the "great oriental goddess", the Magna Mater , and the supporting cultures were determined by matriarchal principles . Overall, the Homo religiosus of the Middle East now sees the divine as personal and transcendent.

Around 7000 BC Then a second male figure joins in, but it was not until the 6th millennium that clear signs of this male deity, often depicted as a bull , were found in Çatalhöyük as part of a pantheon . - Final institutionalization : Above all, settling down together with a worldview that was strongly oriented towards vegetation rhythms offered the prerequisites for the emergence of increasingly differentiated, initially local, religious systems, which now also led to a professionalization of the actors and the establishment of permanent sanctuaries that went far beyond that of the whole The role of the shaman in the Upper Paleolithic went beyond other criteria . In terms of religious anthropology, the question is asked about the reason why the people of that time not only put up with these ever stronger claims to power, but also developed them. These claims were not only related to this world. B. because of the protection of people, fields, herds, houses, equipment and supplies, etc. understandable from marauding nomads. They were also metaphysically based and in some cases, with the establishment of a later judgment for the dead , especially in advanced civilizations, extended beyond death, which now also received a new status, was included in vegetation-mythical contexts and thereby also received a strong earthly chthonic component (underworld). The fact that increasingly stratified, no longer egalitarian societies promote or even force such behavior is likely to lead to an ever increasing instrumentalization of the fear of the sacred, which according to Otto is essential (see above), as well.

Origin of religious awareness and homo religiosus

There are six stages :

- The first stage is the discovery of transcendence: According to Ries, the world of ideas of early man, who created a living space that could be described as culture, tried to understand his environment and asked questions about his own fate, drew from 5 symbols with which with him the first experience of the sacred in the form of what Eliade called hierophany unites, and it results in the formation of a first, as yet incomplete culture. These basic symbols were:

- the vault of heaven by day and night,

- the sun and its course,

- the moon and its variability and the stars and their orbits,

- the symbols of earth and fertility,

- the symbols of the environment such as weather, water, mountains, trees etc.

- The second stage resulted from thinking about death , but also about the mystery of life after death. Clear evidence of this is provided by the first Middle Paleolithic burial rituals, for example of the Neanderthals at Qafzeh (the interpretation of which is, however, controversial among prehistorians ). They show feelings of sharing and affection, especially through grave goods and manipulation of and protective measures for the corpse. Direct conclusions about the attitude towards life after death cannot be drawn with certainty here. However, one can conclude that there was a growth in consciousness in this context, which should have intensified in the subsequent Homo sapiens sapiens . Such burial rites can be clearly traced back to the Upper Palaeolithic . They are considered to be relatively reliable evidence of the rapidly increasing ability to transcend.

- The third stage is characterized by the appearance of the Franco-Cantabrian cave art , the core area of which extends over 20,000 years. Mythograms are their special characteristic. Although their exact contents can no longer be deduced, together with the rich pictorial symbolism they are a feature that indicates the existence of myths, which in turn found their practical expression in rites, be it initiation or hunting rites. First of all, there are sacred stories that are passed on in the clan. Religious awareness has thus expanded on an individual as well as on an ever broader collective basis, especially since one assumes the existence of central, supraregional cave sanctuaries, which were no longer a place of residence, but only a sanctuary.

- The fourth stage begins with the transition to the early Neolithic , which appears epipalaeolithic in Palestine as the transition culture of Natufia . The first representations of the deity can now be found, initially mostly only female, later also the bull as a male god symbol. The French early historian Jacques Cauvin pointed out as early as 1987 that this is not just a simple form of transcendence and the divine, but its symbolic implementation and representation. For the first time, the relationship between man and deity is manifested, which represents a completely new quality in the consciousness of Homo religiosus ; and accordingly people appear for the first time in a prayer position with arms stretched towards the sky (so-called adorant position ), an absolute novelty.

- The 5th stage includes the personification of the divine and its symbolic representation through statues , with temples and sanctuaries emerging where the encounter with the gods can take place. This is especially the case in the early advanced civilizations such as Egypt and Mesopotamia. Chests of priests are created. The temple is the deity's abode, where extensive sacrifices are made to her. Prayer texts are laid down, sacred texts emerge. At the same time, the human realm isolates itself from the sacred. A distancing becomes perceptible, as already postulated by Jensen for the change from ancestral cult to polytheism, and which in later Greek and Roman cultures even leads to a certain contempt for gods in the context of secularization.

- According to Ries, who cannot deny the Catholic priest here, with the growth of the great monotheistic religions, the 6th stage finally shows the discovery of a single omnipotent personal being and creator of the world , who reveals himself, interferes directly and demanding in the lives of his believers , Demands submission and sends out messengers like the Old Testament prophets, Christ and Mohammed. With this, however, the phase of Christian theophany has also been reached, which differs from that of earlier and other religions by an elementary claim to absoluteness .

Brief research history

The subject of religious anthropology has now largely established itself as a subdiscipline of religious studies at the universities where it is taught. However, anthropological approaches in the field of religious studies existed in the 19th century before Julien Ries and others founded the subject in the late 1980s. However, in the absence of reliable archaeological and ethnological findings and the comparatively low level of the corresponding scientific techniques, they remained largely speculative, were philosophical-phenomenological and oriented towards evolutionary biology. At first they were rather a secondary topic of other hermeneutical approaches with difficult delimitations from the sociology of religion and the ethnology of religion. Nevertheless, it was soon clear that anthropology could make a significant contribution to the study of religion.

Spiritual-historical forerunner: Early modern humanism combined with the discovery of the New World had given the first impulses to deal with other and earlier phases of religion, and one began to increasingly gather information. The Age of Enlightenment finally began to deal with it theoretically. Charles de Brosses founded the ethnology of religion with the concept of fetishism in 1760 , and Giambattista Vico wrote the first hermeneutics of myths, cultures and civilizations. Jean Jacques Rousseau and the Sturm und Drang turned against the Enlightenment and saw in religion the reflection of the language of nature, a path that ultimately led to the romanticism of Johann Gottfried Herder and Joseph Görre , to which the religious philosophy of Friedrich Schleiermacher around the The turn of the 19th century contributed quite a bit. The discovery of old religious manuscripts from the Indian field founded Indology and led to new knowledge about Buddhism. The decipherment of hieroglyphics by Jean-Francois Champollion 1816 made it possible to look at the ancient Egyptian culture as already 1802, the decipherment of cuneiform by Georg Friedrich Grotefend "speak" the cultures of Mesopotamia to began and about the Flood Forecast with the history of Noah Utnapishtim in the original made accessible. The archeology, which had hitherto been carried out primarily under the aspect of treasure hunt, began to research more systematically, for example in Mesopotamia and Egypt, where Emperor Napoleon in particular played a key role with his Egyptian campaign from 1798–1801. Auguste Comte, in turn, the founder of positivism , adopted the theory of fetishism from Brosses.

Early phase: In the wake of colonial expansion and the increased missionary activity of the churches, Europe rediscovered a large part of the religious heritage of humanity in the 19th century. After romanticism in particular had aroused interest in foreign peoples and ancient times, but also under the influence of positivism , serious research on religious anthropology probably began with Friedrich Max Müller , the founder of the first genuine comparative religious studies. He held the view that people had always suspected the divine and had an idea of the infinite based on natural phenomena. Lucien Lévy-Bruhl turned to the meaning of symbols and tried on this basis to understand the religious experience of the “primitive peoples”, to whom he ascribed a “ prelogical consciousness”, but as a positivist thinker basically viewed every religion as superstition. Even the term “primitive peoples”, which incidentally appears again and again in literature well into the 20th century (for example in SA Tokarew , who also speaks of “backward peoples”), shows the then widespread perspective of Eurocentrism , see above that such research must at least in part be viewed as ideologically colored, as was not uncommon in the 19th, but also in the 20th century, even if under other ideological auspices .

Ethnology, psychology: The terms mana, totem and taboo also began to interest ethnologists in particular. Above all, Émile Durkheim should be mentioned here, who suspected the origin of religions in totemism . Marcel Mauss , Durkheim's student, dealt primarily with the social function of the sacred and extended the totemic conception to all religions, including the religions of the book. Under the influence of the founder of the peoples' psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, and James George Frazer , Sigmund Freud took a psychologizing direction and believed to discover an analogy to obsessional neurosis in taboo . The same applies to CG Jung with his concept of the archetype , which is also essential from a religious and anthropological perspective , and which influences mythologists to this day.

The evolutionist direction became particularly significant towards the end of the 19th century under the influence of the theories of Charles Darwin , but also of the materialism of Karl Marx, and in some cases strongly overlapped other approaches. One of its first representatives is John Lubbock ; In Germany, the theologian and philosopher Rudolf Otto drafted a concept that also points in the evolutionist direction, which differentiates God's unique holiness from his ethical qualities. The main representatives, however, are Herbert Spencer , after whom the cult of ancestors formed the root of every religion, EB Tylor , the founder of British anthropology, with the idea of transformism that already emerged in Spencer, which draws a direct line from animism to monotheism. Wundt, Durkheim and Mauss also created their entire work on this evolutionist basis, which applied the scheme of evolution to religion and excluded any supernatural. The work of Robert Ranulph Marett , who adhered to evolutionism, but distinguished between a biological and a philosophical evolutionism and coined the term animatism , forms a certain transition .

Materialism, empiricism, functionalism: the materialistic philosophy of Karl Marx , which referred to Hegel's work, pointed a different path, which primarily promoted evolutionism, but was also followed in its materialistic component by Soviet authors such as SA Tokarev until the end of the 20th century . The now increasing anthropological and ethnological field research also contributed new material from non-literate cultures and allowed more well-founded, factually supported statements that stood out from the ideological basic currents of their time. The migration theory of Friedrich Ratzel and the culture area theory of Leo Frobenius belong in this context . Andrew Lang , who developed the theory of "primordial monotheism", and Wilhelm Schmidt , who pursued the same idea, finally turned completely away from evolutionism at the end of the 19th century, and overall the idea now prevailed, the belief in a supreme being stand at the beginning of the religious thinking of many archaic peoples. For these religious anthropological contexts out now developed religious history as a science. Functionalism

was also increasingly finding its way into religious studies, as had already been shaped by research on totemism and fetishism, for example by Durkheim and by Freud. In addition, the connections between myths and ritual now played an increasingly important role, for example with Bronislaw Malinowski . Myths were also the main research subject of Claude Lévi-Strauss , who adhered to a more formal structuralism and is therefore viewed rather skeptically by modern anthropologists. At the end of the 19th century, the rather remote theory of Panbabylonism assumed that the astral worldview of Mesopotamia had shaped all religions.

With the progressive research of prehistoric art, in particular the Franco-Cantabrian cave art by Henri Breuil , André Leroi-Gourhan , A. Laming-Emperaire, Emmanuel Anati and Denis Vialou, there was a further possibility to classify very early religious expressions of humans also anthropologically and culturally. The same applies to the archaeological findings, which have always been refined in terms of excavation technology, and which allow conclusions to be drawn about religious ideas about burials.

Religious anthropology : These divergent currents within religious studies increasingly showed the importance of an anthropologically defined approach to religiously defined concepts such as the sacred, transcendence, symbol, myth, etc. a. that went beyond purely religious phenomenological considerations and sought its center in people themselves. As early as the middle of the last century, Mircea Eliade had begun to follow this path in the course of his research on shamanism, which ultimately led, parallel to the phenomenology of religion, to the anthropology of religion, which was largely co-founded by Ries.

See also

literature

- Wilhelm Karl Arnold , Hans Jürgen Eysenck , Richard Meili (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Psychology. 3 volumes, 11th edition. Herder, Freiburg 1993, ISBN 3-451-23129-8 .

- Mircea Eliade : History of Religious Ideas. 4th volumes. Herder, Freiburg 1978, ISBN 3-451-05274-1 .

- Mircea Eliade: Shamanism and archaic ecstasy technique. 8th edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1994, ISBN 3-518-27726-X (original 1951: Le chamanisme et les techniques archai͏̈ques de l'extase ).

- Sigmund Freud : Totem and Taboo. 9th edition. Fischer, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-596-10451-3 (original 1913).

- Adolf Ellegard Jensen : Myth and cult among primitive peoples. dtv, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-04567-1 (original 1951).

- Carl Gustav Jung : basic work. Volume 2: Archetype and Unconscious. 4th edition. Walter, Olten 1990, ISBN 3-530-40782-8 (original 1934 ff).

- André Leroi-Gourhan : The religions of prehistory. Paleolithic. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1981, ISBN 3-518-11073-X (original 1964).

- Klaus Schmidt : You built the first temple. The enigmatic sanctuary of the Stone Age hunters. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-53500-3 .

- Ken Wilber : The Spectrum of Consciousness. A metaphysical model of consciousness and the disciplines that explore it. Scherz, Bern, 1987, ISBN 3-502-15852-5 .

- David Lewis-Williams: The Mind in the Cave. Consciousness and the Origins of Art. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-28465-2 (English).

- Erhard Oeser: The self-confident brain. Perspectives of Neurophilosophy. WBG, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-534-19068-8 .

- Julien Ries u. a. (Ed.): Trattato di anthropologia del sacro. 10 volumes, Milano, Jaca Book 1989–2009 ( On the anthropology of the saint ).

- Julien Ries: Origin of Religions. Pattloch, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-629-00078-9 .

- Natale Spineto, Fiorenzo Facchini , Julien Ries: The symbols of humanity. Patmos, Ostfildern 2003, ISBN 3-491-96145-9 .

- Sergei Alexandrowitsch Tokarew : Religion in the history of peoples. Dietz, Berlin 1968.

Web links

- Hans-Rudolf Wicker: Guide for the introductory lecture in anthropology of religion, 1995–2012. (PDF: 292 kB; 51 pages) Institute for Social Anthropology, University of Bern, 2012 (lecture notes).

Individual evidence

- ↑ In the English-speaking world, religious / religion anthropology is usually used in the sense of the sociology of religion.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 516/517.

- ↑ This German term also has a different meaning in American, where cultural anthropology or in English social anthropology denotes a special orientation in ethnology .

- ^ Brockhaus encyclopedia. Volume 12, p. 583.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 521/522 and 528.

- ^ Arnold / Eysenck / Meili, pp. 1882–1895; Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 517/518.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 517/518 and 525-528.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 524/525.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 518/519 and 525.

- ↑ Brockhaus. Volume 1, p. 633.

- ↑ a b PDF at www.jacabook.it

- ↑ Ries, Ursprung der Religionen, pp. 116–156.

- ↑ Ries: Ursprung der Religionen, 1989, p. 115.

- ↑ a b c Ries: Origin of Religions, p. 134.

- ↑ Hans-Rudolf Wicker: Guide for the introductory lecture in anthropology of religion, 1995–2012. (PDF: 292 kB; 51 pages) Institute for Social Anthropology, University of Bern, 2012 (lecture notes).

- ↑ Ulrich Schnabel: Religious Studies: The adjusted faith . In: The time . No. 08/2009 ( online ).

- ^ Arnold / Eysenck / Meili, Volume 1, p. 150.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Ries: Origin of Religions, p. 157.

- ↑ Spineto, p. 7 ff.

- ↑ Brockhaus. Volume 21, p. 518.

- ↑ Brockhaus. Volume 21, p. 519.

- ↑ Not to be confused with Freud's super-ego . Rather, what is meant here are the transcendent or metaphysical regions.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 121/122.

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, pp. 104-107.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 122, 142–149.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, p. 126.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 34–42, 50–53, 119–122.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 127-133.

- ↑ Lewis-Williams, pp. 216-220.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, p. 43.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 43–53, 58–61.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 54–82.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 150–152.

- ↑ Brockhaus. Volume 22, p. 328.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 146/147.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 150/151.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, p. 153.

- ↑ a b Ries: Origin of Religions, p. 116 ff.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, pp. 770-773.

- ↑ Brockhaus. Volume 9, pp. 606/607.

- ↑ Wilber, p. 22 ff.

- ↑ Oeser, pp. 27, 184-196.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 78–82, 87–114.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Schmidt, pp. 243-257.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 66/67.

- ↑ Ries: Origin of Religions, pp. 153–156.

- ^ In: L'apparition des premières divinités. La Recherche, Paris 1987, pp. 1472-1480.

- ↑ Jensen, pp. 164/165.

- ↑ Tokarew, pp. 120 ff.

- ^ Britannica. Volume 26, p. 514 ff .; Ries: Origin of Religions. Pp. 11-25.