metaphysics

The metaphysical ( latin metaphysica ; Greek μετά META , then ',' rear ',' beyond 'and φύσις physique , nature ', 'natural texture') is a basic discipline of philosophy . Metaphysical system designs deal with the central problems of theoretical philosophy in their classic forms, namely the description of the foundations, prerequisites, causes or "first justifications", the most general structures, laws and principles as well as the meaning and purpose of the whole of reality or of all being .

Specifically, this means that classical metaphysics deals with “ultimate questions”, for example: Is there a final meaning why the world exists at all? And for the fact that it is set up the way it is? Is there God / gods and if so, what can we know about it? What is the essence of man? Is there such a thing as “spiritual”, especially a fundamental difference between spirit and matter ( body-soul problem )? Does man have an immortal soul , does he have free will ? Does everything change or are there also things and connections that always remain the same despite every change in appearance?

According to the classical explanation, things of metaphysics are not accessible through individual empirical investigations, but areas of reality on which they are based. The claim to formulate knowledge outside the limits of sensory experience has also been criticized in many cases - approaches of a general metaphysics criticism have accompanied the metaphysical system attempts from the beginning, but were developed especially in the 19th and 20th centuries and are often understood as a characteristic of modern worldview been. On the other hand, questions about a final meaning and a systematically describable “big picture” have been created as a natural way in humans , understood as an “uninhibited need” ( Kant ), and even humans as an “animal metaphysicum” , as a “living being that drives metaphysics “( Schopenhauer ). Since the middle of the 20th century, despite the classic analytical-empirical and continental criticism of metaphysics, complex systematic debates on metaphysical problems have been conducted again by philosophers who are mostly analytically trained.

Concept history

According to today's majority opinion, the term “metaphysics” comes from a work by Aristotle , which consisted of 14 books of general philosophical content. In the first Aristotle edition , the Peripatetic Andronikos of Rhodes (1st century BC) classified these books behind his eight books on " physics " (τὰ μετὰ τὰ φυσικά tà metà tà physiká , 'that after / next to physics'). This gave rise to the term “metaphysics”, which actually means: “that which is behind the physics on the shelf”, but at the same time didactically means: “that which follows the explanations about nature” or scientifically and systematically means: “that what comes after physics ”. Which of the two points of view is considered to be more original is controversial among historians of philosophy. The exact meaning of the word at that time is unclear. The term is documented for the first time with Nikolaos of Damascus . Aristotle himself did not use the term.

Since late antiquity , “metaphysics” has also been used to name an independent philosophical discipline. In late antiquity and occasionally in the early Middle Ages, metaphysics was also given the name epopty (from Greek to look, to grasp). On the other hand, the adjective “metaphysical” has been used in a pejorative way, especially since the 19th century, in the sense of “doubtful speculative”, “unscientific”, “senseless”, “totalitarian” or “non-empirical thought gimmick”.

introduction

Topics of metaphysics

The aim of metaphysics is the knowledge of the basic structure and principles of reality. Depending on the philosophical position, metaphysics can refer to different, i. a. extend very broad subject areas.

In addition, classical metaphysics poses a basic question that can be formulated as follows:

- Why is there being at all and not rather nothing? What is the reality of the real - what is the being of beings ?

This question of a final explanation of what constitutes reality as such is of a more fundamental nature than the specific individual questions of classical metaphysics. In general metaphysics, for example, the question is how a connection between all beings is constituted and, classically, often also how this overall connection can be meaningfully interpreted .

In detail, classical metaphysics deals with topics such as:

- How are the basic concepts and principles of ontology to be analyzed, such as being and nothing , becoming and decay, reality and possibility , freedom and necessity, spirit and nature, soul and matter, temporality and eternity , etc.?

- What corresponds to the building blocks of our sentences and thoughts, what do they refer to, how are they made true? For example, what is the relationship between the individual (individual objects) and the general (such as the property of being red)? Does the general have an independent existence? Do numbers exist? (see also the article Universals Problem )

- What about the reference of normative and descriptive, value and being statements? How about religious beliefs? What makes each of these true? Are there any moral objects (values, facts)? Is there a first principle of reality that can be identified with a god? How would they be? How exactly would you relate to us?

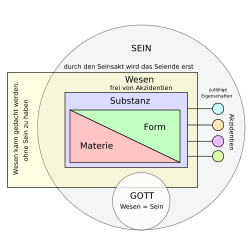

Metaphysics develops basic concepts such as form / matter , act / potency , essence , being , substance , etc.

Insofar as these basic concepts of all beings can be expressed, they are called categories in Aristotle, Kant and the authors who refer to them . However, it is partly unclear in the interpretation whether categories are mere words or concepts or whether they correspond to independently existing objects or types of objects.

Various individual philosophical disciplines are based on metaphysical concepts, and indirectly also various individual sciences . In this respect, metaphysics can be viewed as fundamental to philosophy in general.

Systematics and methodology

Traditionally, metaphysics is divided into a general ( metaphysica generalis ) and a special ( metaphysica specialis ) branch; the first is ontology , the other includes rational theology , psychology and cosmology :

- The general metaphysics has all sciences the highest level of abstraction ; it asks about the most general categories of being and is therefore also called fundamental philosophy. It is concerned with what things , properties or processes are essentially and how they relate to one another. Insofar as it examines beings as beings, one speaks of ontology or the doctrine of being.

- The rational theology asks for the first cause all being, d. H. according to God as the highest being and as the basis of all reality. This philosophical sub-discipline is also called philosophical or natural theology .

- The rational psychology deals with the soul or the (human) spirit as a simple substance.

- The rational cosmology studies the nature of the world, d. H. the connection of all beings as a whole. As a doctrine of the structure of the material world as a natural system of physical substances , it has essentially coincided with natural philosophy since ancient times .

Metaphysics can proceed in different ways:

- It is deductive or speculative if it starts from a supreme principle, from which it gradually interprets the overall reality. Such a highest principle could be the idea , God, being, the monad , the world spirit or also the will .

- It is inductive , if they consider combines all the individual sciences in a synopsis in the trial, the results, creates a metaphysical worldview.

- However, it can also be understood as reductive (neither empirically-inductive nor speculative-deductive) if it is only understood as a speculative exaggeration of those convictions that people must always assume in order to be able to recognize and act at all.

A critical reflection of their own basic concepts, principles and argumentation structures belonged to metaphysics from the beginning as well as a demarcation from the other philosophical disciplines and the individual sciences ( physics , mathematics , biology , psychology , etc.).

Metaphysical positions

Basic concepts and problems of metaphysics

Be

Univoker and analogous concept of being

The underlying concept of being is of decisive importance for the statements of the respective metaphysics. In the tradition there are two fundamentally different approaches:

In a univocal understanding of being , “being” is understood as the most general characteristic of any things (called “being” or “ entities ”). It is what all beings still have in common after subtracting the respective individual properties: that they are , or in other words: that all being belongs to them (cf. ontological difference ). This concept of being leads to a “metaphysics of being”. “Being” (essentia) here refers to properties (such as that which makes every human being a human being), “being” (existentia) to existence. For example, Avicenna and its reception distinguish between (the early) Thomas Aquinas (concise and well-known in De ente et essentia ).

In an analogous understanding of being , “being” is understood as that which belongs to everything , albeit in different ways ( analogia entis ). Being is that in which on the one hand all objects agree and in which they differ at the same time. This understanding of being leads to a ( dialectical ) “metaphysics of being”. The counter-concept to being here is nothing, since nothing can stand outside of being. Being is understood here as fullness. An example of this approach is provided by Thomas Aquinas' late philosophy ( Summa theologica ).

Uses of "being"

In the ontological tradition, "being" is the central basic concept. Basically, three ways of using the term “being” can be distinguished, which can already be found in Plato : existence (“cogito, ergo sum”), identity (“Kant is the author of the Critique of Pure Reason”) and predication (“Peter is a Human"). In traditional ontology, the question is discussed how the His behavior toward beings. Martin Heidegger speaks of the " ontological difference " , which stands for the separation of existentiality (man as being in the world ) and categoricality (worldless).

The most common use of the word “is” is in the sense of predication. According to the classical Aristotelian view, which remained decisive until the 19th century, the word “is”, understood as the copula of the statement, relates the predicate to the subject. Based on this linguistic form, Aristotle comes to his ontology, according to which the world consists of substances and their attributes. In this model, the predicate assigns a general property to an individual.

In analytic philosophy the “is” of the statement is no longer understood as a copula, but as part of the predicate. In this understanding, the “is” stands for a certain connection, the relationship that connects the individual with the property ( exemplification ). At the center of consideration is the sentence as a whole, which relates to a state of affairs.

Categories

Under categories (Greek: kategoria actually "charge", later or "" property " predicate ") is defined as ontological basic concepts with which one basic features of the existent features. Since the verb kategorein translated into Latin Praedicare is hot categories especially in the Middle Ages predicaments .

According to Aristotle, a number of the most general ontological terms can be identified, which at the same time correspond to the highest genera of beings - he names these categories and distinguishes ten of them, including substance, quantity, quality, relations, spatial and temporal localization, etc. a. The purpose of categorization is to show structures in reality and to uncover and avoid logical errors in the description of beings. Categories are used to classify the building blocks that make up the world as a whole or in its parts (domains). They are completely disjoint and to this extent (in contrast to the transcendentalies) no general basic characteristics of all beings. The Aristotelian theory of categories has shaped numerous ontological approaches to the present day and is still considered fruitful by some metaphysicians today, e. B. in formal ontology .

Transcendental

Authors of the Latin scholasticism of the Middle Ages use the term transcendentalia (Latin transcendentalia , from transcendere “to exceed”) to denote those terms that apply to all beings and therefore encompass the classifying categories. While categories are only predicated of certain beings, all transcendentalities apply to every being, but are predicated of different beings in different ways ( analogy ). The true (verum), the one (unum) and the good (bonum), often also the beautiful (pulchrum), are considered to be transcendental . In classical ontology, these transcendentalies were considered to be interchangeable: what was (to the highest degree) good was also considered (to the highest degree) true and beautiful, and vice versa. In the 13th century there was a controversial discussion about how these transcendental terms should be understood. In modern ontology there are further transcendentalities such as reality (actuality), existence, possibility, similarity, identity or difference (difference).

Individuals

In ontology, "individual" (the indivisible; also "single thing", English: particular ) is a basic term that is not defined by other ontological terms . Individuals have characteristics , but they are not used for characterization. Thus, proper names of individuals have no predicative character. You can say something about Socrates , but you cannot use Socrates as a predicate. Furthermore, individuals are characterized by the fact that they cannot be in different places at the same time. Multilocality is only available for properties. Thirdly, according to Gottlob Frege , individuals are saturated entities , that is, they are objects that are self-contained and do not require any further naming.

An important distinction within individuals is that of physical individuals (objects, bodies) and non-physical individuals ( abstractions ). Examples of the latter are institutions, melodies, times or numbers, the ontological character of numbers being disputed. These can also be viewed as properties. Another problem for ontology is the classification of the mental states discussed in the Philosophy of Mind and the related contents of the terms consciousness , mind, soul (see also qualia and dualism (ontology) ). A distinction is also made between dependent and independent individuals. An individual is dependent when it cannot exist without a certain other individual to exist. Examples of this are a shadow or a mirror image. Whether a smile should also be viewed as a dependent individual, or whether it is a pure property, is again controversial. Independent physical individuals are also called substance ( ousia ) in ontology .

It is still controversial whether and to what extent properties that are realized in a substance are to be understood as a special form of individuals, as property individuals. So one can understand the white in the beard of Socrates as a name for a certain unique occurrence. Further examples are the height of a certain person or the speed of a certain car at a certain point in time. Property individuals are sometimes referred to as tropics . They are accidental to a substance, so they always have a carrier and are always dependent.

Facts

Facts are structured entities that relate to constellations in space and time that are composed of individuals, properties and relations. If facts have an equivalent in reality, one speaks of facts . For realistic ontologists, statements about facts have a correspondence in reality that elevate the statements as truth makers to facts.

Ludwig Wittgenstein sketched an ontology in the Tractatus logico-philosophicus that is based entirely on facts. Key sentences:

- "The world is the totality of facts, not of things." (1.1)

- "What is the case, the fact, is the existence of facts." (2)

- “The state of affairs is a combination of objects. (Things, things.) "(2.01)

- "The existence and non-existence of facts is reality." (2.06)

- "The way in which the objects are related in the state of affairs is the structure of the state of affairs." (2.032)

- "The form is the possibility of the structure." (2.033)

There are a number of ontologists, such as Reinhardt Grossmann , who count facts among the fundamental categories of the world. For Uwe Meixner , who in the first step differentiates between the categories of objects and functions, the facts are a fundamental form of the objects in addition to the individuals. Properties and relationships are exemplified in facts. On the other hand, Peter Strawson , for example, has denied that facts have a reality in the world alongside things. Because the concept of fact is not sufficiently clarified, Donald Davidson concluded that theories based on the concept of fact are themselves to be regarded as not sufficiently clarified. David Armstrong is one of the representatives who hold facts as fundamental constituents of the world .

Universals

In contrast to individuals and facts, universals are not bound in space or time. One can distinguish four types of universals. On the one hand, it includes properties that can be attributed to an object, such as the redness in a billiard ball (property universals). Secondly, there are terms that summarize individuals as species and genera, such as Socrates - humans - mammals - living beings (substance universals). Aristotle also included the third case, the relations, under the properties. The relationship “is father of” can be understood as the characteristic of a person through which he is in a relationship with another. Bertrand Russell called this " monism " and rejected it. For him, and subsequently for most ontologists, a relation aRb is a relation R external to the individuals and which exists between the individuals a and b. Properties are "exemplified" in individuals, relations in facts. They have an occurrence in a specific object. Finally, fourth, there are non-predictive universals that have the character of an object and not that of a property, such as the Platonic Ideas, Beethoven's Ninth, the turtle (as a genus) or the high C. Such type objects (types) can be spatial and occur several times in time. There are various performances of Beethoven's Ninth and various printed music. Type objects cannot be expressed by a predicate. You can't say “turtle”.

From the beginning there was the problem of how to classify what is designated with these general terms ontologically (problem of universals ). Opposite each other are positions that assign the universals their own reality in different ways (universal realism) or those who are more convinced that universals are purely conceptual, mental products with which certain characteristics of individual things e.g. B. given a name based on similarity or other criteria (nominalism). A more modern term for universals is "abstract objects". This is primarily intended to make it clear that type objects such as the number Pi are also included in the consideration.

Part and whole

The part-whole relationship ( mereology ) is discussed on different levels. So the head of Socrates is an individual who is a spatial part of the individual Socrates. Because it is part of the essence of Socrates to have a head, the head is called an essential part of Socrates. But there are also group individuals (plural individuals) such as the Berlin Philharmonic, the capitals of the EU or the three musketeers, each of which consists of several individual individuals. The part-whole relationship has a different character. If a musician leaves the Berliner Philharmoniker or another state joins the EU, the character of the group individual does not change, even if the numerical identity has changed. If, on the other hand, one of the three musketeers leaves the group, the character of this group expires. Here individual individuals as parts of the group are constitutive of the whole.

A well-known example of problems arising from the part-whole relationship is the ancient thought experiment of Theseus' ship . Topological terms such as “edge” and “connection” can be examined with mereological means, from which the mereotopology arises. Applications can be found in the field of artificial intelligence and knowledge representation . Because the part-whole relationship is an appropriate characteristic for different entities, it can also be counted among the transcendentalities.

The quantum physicists and science philosophers Werner Heisenberg ("The part and the whole") and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker made an important contribution to this.

Metaphysical criticism

Metaphysics has been subject to fundamental criticism since its inception, but especially since the 17th century. Critics of metaphysics often took a variant of the position that the questions of metaphysics could not be adequately answered with the means available to it. While critics in the 17th and 18th centuries argued primarily with reference to the dependence of human knowledge on empirical objects as objects of knowledge, aspects of the valid use of language as a medium of philosophical knowledge have moved to the center of metaphysical criticism since the end of the 19th century. Kant is often seen as the central author of the critique of metaphysics, who argued at the end of the 18th century that the basic concepts by means of which metaphysics were pursued had no validity for the objects of metaphysics. However, he did not call for the end of metaphysics, but instead advocated a philosophy that is based on a fundamental critical reflection of its methods.

literature

Philosophy Bibliography : Metaphysics - Additional references on the topic

Further literature can also be found in the critique of metaphysics

Classic texts

- Plato: Phaidon (before 347 BC), Politeia (approx. 370 BC), Symposium (approx. 380 BC) and a.

- Aristotle: Metaphysics (Aristotle) (4th century BC)

- Plotinus: Enneads (3rd century AD)

- Thomas Aquinas: De ente et essentia (around 1255; German about being and being ), Summa theologica (approx. 1265–1273)

- Francisco Suárez: Disputationes Metaphysicae (1597)

- René Descartes: Meditationes de prima philosophia (1641)

- Baruch de Spinoza: Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata (1677)

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Monadology (1714)

- Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787)

- Johann Gottlieb Fichte: Basis of the entire teaching of science (1794–1795)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling: System of the transcendental idealism (1800)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Science of Logic (1812-1816), Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences (1817)

- Arthur Schopenhauer: The World as Will and Idea (1819, 1844)

- Martin Heidegger: Being and Time (1927)

- Alfred North Whitehead: Process and Reality (1929)

- Jean-Paul Sartre: Being and Nothing. Attempt of a phenomenological ontology (1943, German 1952)

- José Ortega y Gasset: Man is a stranger. Writings on metaphysics and philosophy of life (lectures German 2008) ISBN 3-495-48104-4

- Theodor W. Adorno: Meditations on Metaphysics , in: ders., Negative Dialektik , Third Part, III; Frankfurt / M. (1966)

History of metaphysics

- Jörg Disse : A short history of occidental metaphysics. From Plato to Hegel. 3. Edition. WBG, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 3-534-15501-7 . (Easy to understand introduction to the essential stages of the history of metaphysics)

- Heinz Heimsoeth : The six great problems of occidental metaphysics and the end of the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 1958.

- Wilfried Kühn: Introduction to Metaphysics: Plato and Aristotle. Felix Meiner Verlag, Hamburg 2017.

- Willi Oelmüller , Ruth Dölle-Oelmüller, Carl-Friedrich Geyer: Discourse: Metaphysics . 2nd Edition. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 1995, ISBN 3-506-99371-2 . (Selection of classic texts from the history of metaphysics with general introduction)

- Wilhelm Risse : Metaphysics: Basic Topics and Problems. Munich 1973.

- Heinrich Schmidinger : Metaphysics. A basic course. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 2000, 3rd edition 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-021350-0 . (Systematic-historical introduction, based on Kant's criticism, with passages from original texts and finally presenting your own draft)

Systematic introductions

- David M. Armstrong : Universals - An Opinionated Introduction . Boulder: Westview Press 1989, ISBN 0-8133-0772-4 . (Very clear introduction with a focus on the problem of universals)

- Tim Crane, Katalin Farkas (Eds.): Metaphysics. A Guide and Anthology. Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-926197-0 . (Useful collection of classical and recent texts)

- Peter van Inwagen : Metaphysics . 2nd Edition. Westview Press, Boulder 2002, ISBN 0-8133-9055-9 .

- Friedrich Kaulbach : Introduction to Metaphysics. 5th edition. WBG, Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-534-04853-9 . (Systematic introduction at a high level)

- Jaegwon Kim , Ernest Sosa (Eds.): Metaphysics - An Anthology . Blackwell, Malden 1999. (Extensive and useful collection of important texts)

- Michael J. Loux: Metaphysics - A Contemporary Introduction . 2nd Edition. Routledge London 2002. (Excellent introduction to modern systematic metaphysics)

- EJ Lowe: A Survey of Metaphysics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-875253-9 . (Next to Loux, one of the best introductions to contemporary debates)

- Friedo Ricken (Ed.): Lexicon of epistemology and metaphysics. Beck, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-406-09288-8 . (Article on individual questions from German lecturers)

- Edmund Runggaldier , Ch. Kanzian: Basic problems of the analytical ontology . Schöningh, Paderborn 1998.

- Ted Sider , John Hawthorne, Dean Zimmerman (Eds.): Contemporary Debates in Metaphysics. Blackwell 2007, ISBN 1-4051-1229-8 . (Contrasts two essays with opposing positions in a debate in each chapter)

- Robert C. Koons, Timothy H. Pickavance: Metaphysics: The Fundamentals. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4051-9573-7 (paperback); ISBN 978-1-118-32866-8 (eBook)

Web links

- Peter van Inwagen : Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Edward Craig : Metaphysics , in E. Craig (Ed.): Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy , London 1998.

- R. Eisler : "Metaphysics" in the dictionary of philosophical terms (1904)

- JB Lotz , W. Brugger : General Metaphysics . 3. Edition. Munich 1967 (according to the neo-scholastic method)

- Jan A. Aertsen : The transformation of metaphysics in the Middle Ages . Information Philosophy, 2008

- Christian Thies : Lecture notes ( Memento from October 12, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Philipp Keller: When things need each other - topics of contemporary metaphysics . Seminar documents ( Memento from September 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Sami Pihlström: The Return of Metaphysics? (PDF; 272 kB) Problems with Metaphysics as a Philosophical Discipline

- METAPHYSICA (international journal on metaphysics and ontology with extensive downloads)

- Eckart Löhr: The metaphysical beginnings of the world .

Individual evidence

- ^ Heinrich Schmidinger: Metaphysics. A basic course. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-17-016308-6 , p. 13.

- ^ Heinrich Schmidinger: Metaphysics. A basic course. P. 14.

- ↑ According to Martin Heidegger, this is the “basic question of metaphysics”, cf. z. B. “ What is metaphysics? ".

- ↑ These two expressions also go back to Heidegger's choice of words, cf. For example, Basic Problems of Phenomenology, GA 24, 137: "Ancient philosophy interprets and understands the being of beings, the reality of the real, as existence" and 152: "What constitutes the reality of the real, the ideas, [are] according to Plato himself the really real ”.

- ↑ Sophistes (237a-263e)

- ↑ See Albert Keller : Being . In: Handbook of basic philosophical concepts . Kösel, Munich 1974

- ↑ See e.g. B. Barry Smith : Aristoteles 2002 (PDF; 108 kB). In: Thomas Buchheim , Hellmut Flashar , RAH King (ed.): Can you still do something with Aristotle today? Meiner, Hamburg 2003, pp. 3–38.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Jorge JE Gracia (Ed.): The Transcendentals in the Middle Ages , Topoi 11.2 (1992); Martin Pickave (Ed.): The Logic of the Transcendental, Miscellanea Mediaevalia Vol. 30, Berlin: De Gruyter 2003

- ↑ Uwe Meixner speaks out in favor of the term individual property : Introduction to Ontology, WBG, Darmstadt 2004, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Kevin Mulligan, Peter Simons, Barry Smith: "Truth-Makers", Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 44 (1984), pp. 287-321

- ^ Herbert Hochberg: The Positivist and the Ontologist. Bergmann, Carnap and Logical Realism, Rodopi, Amsterdam 2001, pp. 128-132

- ↑ Peter F. Strawson: "Truth", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Suppl. Vol. 24 (1950), reprinted in: Logico-Linguistic Papers, Methuen, London 1971

- ↑ Donald Davidson, "The Structure and Content of Truth," The Journal of Philosophy, 1990, pp. 279–328

- ^ David M. Armstrong: A World of States of Affairs. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997 (German: Sachverhalte, Sachverhalte. Berlin 2004), overview as an article: A World of States of Affairs (PDF; 1.4 MB), in: Philosophical Perspectives 7 (1993), 429–440

- ↑ Rolf-Peter Horstmann: Ontological Monism and Self-Confidence (PDF; 128 kB), accessed on June 23, 2012

- ↑ Wolfgang Künne : Abstract Objects. Semantics and ontology. 2nd edition Klostermann, Frankfurt 2007