History of metaphysics

Metaphysics before Immanuel Kant

Antiquity

Even among the pre-Socratics , the central motif of metaphysics appears in the question of what substance or element everything consists of, i.e. That is, at the very beginning of philosophy there is an attempt to understand the world as a whole from a single, unifying (primal) principle ( arché ).

Parmenides is considered to be the founder of ontology . For the first time he uses the concept of being in its abstract form. For him there is only one being that is complete, uniform and recognizable. Because recognizing something also means that it is (DK 28 B 3). There is no non-being, one can neither recognize it nor speak of it (DK 28 B 2). The being is uncommon and immortal. Multiplicity, change and movement of beings are mere appearance; their assumption is based on the errors of mortals, who also have the ability to know (DK 28 B 16). Parmenides had a great influence on the further development of the metaphysical discussion. His thoughts continued to have an impact on Plato and Aristotle to Christian theology and philosophy of the Middle Ages .

Center of the philosophy Plato is the idea ( idea ). In the Platonic Dialogues , Socrates asks what is just , brave , pious , good , etc. Answering these questions presupposes the existence of the ideas expressed in the general terms. The idea is that which remains the same in all objects or actions, however much they differ from one another. It is the form ( eidos ) or the essence ( usia ) of things. With Plato, the ideas are recognized through a kind of spiritual “vision” ( theoria ). This show takes place in dialogue, which requires the art of correct conversation ( dialectic ). It is a " remembrance " ( anamnesis ) of the immortal soul of the ideas seen before birth .

The ideas are the "archetype" ( paradeigma ) of all things. They are placed before the individual things that only participate in them ( methexis ). Only they are being in the true sense of the word. The visible individual things only represent more or less perfect images of the ideas. Their place is between being and non-being.

For Plato the highest idea is the idea of the good . It is the principle of all other ideas and belongs to a higher order. At the same time it is the ultimate goal and meaning of all human activity. Not only the virtues, but the essence of everything is only known through the good. Because only when a person knows what a thing is “good” for, ie what its goal ( telos ) is (cf. also teleology ), is he able to recognize his true “essence”. This is where the ultimately ethical background of Platonic metaphysics becomes apparent .

Plato's theory of ideas was often understood in the tradition to mean that he assumed a separate existence of the ideas. This doctrine of two worlds ( dualism ) led to a universal dispute in the Middle Ages .

For Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC), who founded metaphysics as an independent discipline, it marks the absolute beginning of all philosophy, which precedes all individual scientific questions. Their research is only concerned with certain sub-areas or aspects of reality or beings, but not with the underlying prerequisites of this reality or beings. Because it examines the fundamental laws of the theoretically thematized reality, Aristotle also calls metaphysics " First Philosophy " ( Philosophia prima ), which precedes the Secunda philosophia ("Second Philosophy"), namely the investigation of nature ("Physics").

Aristotelian metaphysics is a science of the essence of beings as well as the first reasons of being. It tries to conceptualize what is; H. it reflects the conceptual structures of reality and its comprehension - also with regard to the empirical sciences. Aristotle attempts to establish philosophy on solid ground with the help of generally applicable logical principles such as the principle of contradiction or the principle of excluded third parties .

The clarification of the ontological foundations is at the same time the search for the unity and all-unity of beings as the basis of all reality. Aristotle sees God as the sole cause of all being. Metaphysics inevitably goes together with philosophical or natural theology. Together with some Platonic dialogues , whose idealistic approaches Aristotle takes up in a transforming way, the metaphysics of Aristotle has remained the basic book of metaphysics to this day, which has shaped the metaphysical specialist terminology (see above) (see also Aristotelism ).

Since philosophers of earlier times were often universal scholars, the writings of Aristotle include both writings with metaphysical content and treatises on botany and zoology, etc. A complete separation of metaphysics and natural sciences will only become established in the Renaissance . For the scholars of antiquity, it was only logical to deal with the things that could be experienced and to ask questions about the last (or first) reason for these things. The study of concrete phenomena gave rise to the natural sciences, which deal with the relationships between things (of beings) and describe their states and interactions within the nature that humans can recognize.

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages , metaphysics is considered the "queen of the sciences" ( Thomas Aquinas ). She is faced with the task of uniting the ancient tradition with the specifications of Christian teaching . Prepared by neo-Platonism in late antiquity , it tries to speculatively portray “true being” and God, i.e. H. to be recognized with the help of pure reason .

Central themes of medieval metaphysics are the differences between divine and worldly being ( analogia entis ), the doctrine of transcendentalies and the evidence of God . God is the undoubted, absolute foundation of the world. He created them out of nothing ( creatio ex nihilo ) and put them in their order “according to measure and number” ( Weish 11.20 EU ). Influenced by the ancient Platonic philosophy, metaphysics manifests itself as a kind of 'dualism' of "this world " and " beyond ", of "mere sensual perception" and "pure thinking as sensible cognition", of inner-worldly " immanence " and other-worldly " transcendence ".

A fundamental question of medieval metaphysics - as of all metaphysics - is how it can be possible for human rationality to share in the eternal and absolute divine truths. The blanket denial of this possibility is just as contradictory as a radical metaphysics rejection (see below).

Beginning of the modern age

With the beginning of the modern age , which marked the beginning of the decline of traditional ontological-theological metaphysics, humans became the sole yardstick of philosophy ( subjectivism ): René Descartes (1596–1650) was the first to pursue the methodical approach to transform metaphysics into the subject “ to bring it in ”and to base it on pure subjective certainty free of empirical experience . He assumed that humans have innate ideas ( ideae innatae ) of phenomena such as "God" or the "soul", which are of the highest, unquestionable clarity or evidence . The empiricism ( John Locke , David Hume (1711–1776)), which they with “If we pick out any volume, for example about the doctrine of God or school metaphysics, we should ask: Does it contain any abstract train of thought about size and number? No. Does it contain any experiential train of thought about facts and existence? No. Now throw it into the fire, because it can contain nothing but delusion and deception ” , on the other hand denied the existence of such innate ideas as the basis of the knowledge of reality and was naturally skeptical of metaphysics.

The first book of the modern age that dealt specifically with metaphysics was the Disputationes metaphysicae (1597) by Francisco Suárez . This was followed by scholastic school metaphysics, which Christian Wolff (1679–1754) brought to a final synthesis through the connection with the teaching of Descartes , and which Kant - partly wrongly - considered "the classical form of metaphysics".

At the same time it is becoming increasingly questionable for contemporaries: Metaphysics is perceived as "dark", "dogmatic" and "useless"; Johann Georg Walch even describes it as a "philosophical lexicon of dark artificial words that does not create the slightest use".

Immanuel Kant's criticism

Kant also means a “ Copernican turn ” for metaphysics . Classical metaphysics appears to him only as an “ empty phrase ” - on the other hand, he feels obliged to its universal claim. He wants to establish a metaphysics " that will be able to appear as science ". To do this, he must investigate whether and how metaphysics is even possible . According to Kant's approach, the ultimate questions and the general structure of reality are inextricably linked with conditions in the subject. For him, this means systematically describing the foundations and structures of human knowledge and determining the limits of their scope, in particular distinguishing between possible and illegitimate claims to knowledge ( criticalism ). Kant presents this analysis with his Critique of Pure Reason (1781/87). The decisive factor here is the epistemological requirement that in principle reality only appears to people as it is conditioned by the special structure of their cognitive faculties. Access to knowledge on "things in themselves" independently of these knowledge conditions is therefore impossible.

For Kant, knowledge presupposes thinking and perception . Metaphysical objects such as “God”, “soul” or a “whole of the world” are not clearly given. Traditional metaphysics is therefore impracticable. It would have to presuppose a "spiritual intuition", a faculty of knowledge that would have access to ideal objects without sensual intuition. Since we do not have such a faculty, traditional metaphysics is merely speculative- constructive. According to Kant, for example, in principle it is not possible to come to a rational decision on the central questions, whether there is a God, a freedom of will, an immortal soul. His conclusion is:

“Human reason has a special fate in one species of its knowledge: that it is troubled by questions that it cannot reject; for they are given to it by the nature of reason itself, which it cannot answer either; because they exceed all capabilities of human reason. "

Starting from practical-moral action, Kant tries to re-establish metaphysics in the Critique of Practical Reason . The practical reason put necessary " postulates to" the fulfillment of which is a prerequisite moral action:

- The freedom of the will must be required as a moral law has no meaning if it does not at the same time gives the freedom of the one who is to fulfill the law.

- The immortality of the soul is necessary because the concrete human being in his natural existence, seeking happiness, can only approach the moral law “in an infinite progressus ”; this approach only makes sense provided that death does not make it worthless, but gives it meaning “beyond life”.

- But only through the existence of God is it guaranteed that nature and moral law will ultimately be reconciled with one another. God can only be imagined as a being who is both the “cause of all nature differentiated from nature” and an “ intelligence ” acting out of a “moral disposition” .

German idealism

The movement of German idealism , which some see as the culmination of the development of metaphysical systems as far as speculative and systematic thinking is concerned , proceeds from Kant (who distanced himself from it and resisted attempts to make friends) . This school of thought - mainly represented by Fichte, Schelling and Hegel - regards reality as a spiritual event in which the real is " suspended " into the ideal being .

German idealism adopts Kant's transcendental turn, i. That is, instead of understanding metaphysics as the striving for objective knowledge, he deals with the subjective conditions of their possibility, i.e. the extent to which a person is even capable of such insights based on his constitution. But he tries to overcome the self-limitation of knowledge to possible experience and mere appearance and to get back to a point at which metaphysical statements can again claim absolute validity: "absolute knowledge", as it is called from Fichte to Hegel. If - as Kant said - the contents of knowledge only apply in relation to the subject, but this point of reference is itself absolute - an "absolute subject" - then the knowledge related to it (valid for the absolute subject) also has absolute validity. From this starting point, German idealism believes that it can transcend the empirical opposition between subject and object ( subject-object split ) in order to get a grip on the absolute .

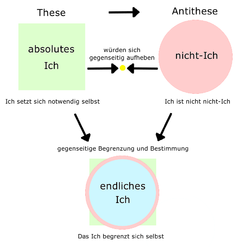

For Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) the absolute is the “absolute I” or the absolute subject. This is essentially characterized by its activity, the " act of action ", in which self and object consciousness coincide. Fichte goes so far as to speak of “I in myself”. The object opposite to the ego becomes with him a mere “not-me”.

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854) objects that the subject-object duality is not really exceeded, but rather the absolute falls back into the one pole of opposition, subjectivity. The absolute is conceived of as a purely I-like, subjective quantity, while its objectivity is annulled as a mere not-I. The object must be understood as the equivalent opposite pole of the subject and the subject-object duality must be transcended even more radically. This leads Schelling to “ absolute identity ”, which is “ absolute indifference ” before all difference, even before the first and highest difference in consciousness between subject and object , neither subject nor object or both at the same time in an absolute or undifferentiated unity (cf. Coincidentia oppositorum ).

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), on the other hand, objects that no difference whatsoever can arise or be understood from pure and absolute identity (this identity is "the night when all cows are black"): reality in all its diversity is thus so not explainable. The “identity of the absolute” must therefore be thought of in such a way that it originally contains both the possibility and the necessity of differentiation. This means that the absolute realizes itself in its identity through the establishment and cancellation of non-identical moments. Hegel opposes Schelling's “absolute identity” with dialectical identity: the “identity of identity and non-identity”. From this point of departure he develops what is probably the last great system of occidental metaphysics in the science of logic .

The break with metaphysics

From the middle of the 19th century there was a strong disenchantment with metaphysics. The word of the “ collapse of the metaphysical systems” is making the rounds and leads to the emergence of positivist currents. The task of the human spirit is now to control and calculate reality, no longer the question of its meaning. The natural sciences as a whole are now temporarily assuming the role of the basic sciences . They see in metaphysics only the wrong questions asked or purely pseudo-problems dealt with and demand the abdication of a discipline which in its supposedly “pre-scientific questions” ( Auguste Comte ) about the nature and meaning of things only “falsifies” reality. The reorganization of philosophy into a pure epistemology and science theory, giving up its metaphysical character, then led to the foreseeable instrumentalization of the former universal science by the individual sciences. Metaphysics should now only design “ world views ” that are supposed to satisfy a “general need” for meaning and orientation.

Metaphysics in the 20th Century

Metaphysics was also often criticized in the 20th century because of its supposedly unclear objectives, complicated conceptual structures and the lack of an intersubjectively verifiable reference to experience. She was attacked in particular from the camp of language analytical philosophy , logical empiricism and the theory of science .

Especially the positivism threw metaphysics again and again that it does not reflect its (linguistic) basis and spend as theories, which only "feelings" were. “Metaphysicians are musicians with no musical ability,” says Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970). For Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) philosophy is a “fight against the bewitching of the mind through the means of our language”. She is there when she has saved herself. At the end he even distances himself from his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus , which naturally has a metaphysical character, with the words "My sentences are explained by the fact that those who understand me ultimately recognize them as nonsensical". Karl Popper (1902–1994), who criticized positivism, also turned against its hostile relationship to metaphysics. However, he did not assign metaphysics the function of a secure foundation for the establishment of knowledge, but rather the function of metaphysical research programs that stimulate the development of scientific theories. These theories then contain the metaphysical idea as a logical consequence, but are empirical as a whole. From this point of view, metaphysics is not an epistemological prerequisite for science, but a consequence of its speculative theories. Gerhard Vollmer, who took the opposite point of view, weakened the demands of the positivists for a “science free of metaphysics” to a “ minimal metaphysics ” that only contains logical prerequisites for the scientific process of knowledge that cannot be scientifically proven, e. B. the uniformity of the world.

On the other hand, there were also new attempts at access to classical metaphysics in the 20th century. The phenomenology of Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) was based on the founding ideal of the First Philosophy. With Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) there was also an appreciation of ontology when he presented a completely transformed theory of being. His fundamental ontology , which was dedicated to the existential analysis of human existence , represented a radically new approach for the modern age . Nicolai Hartmann (1882–1950) (“categorical-analytical layered ontology”) and Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) also have considerable new designs daring. In the last thirty years there have been attempts in the Anglo-Saxon world to formalize and axiomatize metaphysics, for example in EN Zalta.

Important approaches

Almost all philosophers address ontological issues in their work. This applies to modern thinkers such as the existentialists (e.g. Jean-Paul Sartre ) as well as to phenomenological thinkers such as Edmund Husserl , Martin Heidegger or numerous analytical philosophers such as Willard Van Orman Quine and Peter Frederick Strawson , and to ancient thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle and Medieval Plotinus or thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas.

Parmenides

Parmenides was one of the first to undertake an ontological characterization of the fundamental nature of being. In the prologue or preface of his didactic poem by nature , he describes that nothing comes from nothing, and therefore the being is eternal. Therefore, our opinions about the truth are often wrong and deceptive. According to the instructions of the goddess, two paths lead to the goal: the path of truth and the path of opinions. The first agrees with unity, the second with multiplicity. It is only an appearance. Thinking presupposes being. Much in Western philosophy and science - including the basic concepts of falsifiability and the law of conservation of energy - have emerged from this view. This science posits that being is what can be conceived, created, or possessed by thinking. According to Parmenides, there can be neither emptiness nor vacuum, and true reality can neither arise nor perish. Rather, the totality of beings is eternal, unique, uniform and unchangeable, immobile, even if not infinite. Parmenides therefore postulates that change as perceived in everyday experience is only an illusion. In this he agrees with his student Zenon von Elea , to whom the turtle paradox is ascribed. Everything that can be recorded is only part of a comprehensive unit. This idea anticipates the modern concept of one final great unifying theory that explains all existence in terms of an interconnected sub-atomic reality that is unreservedly valid.

Thomas Aquinas

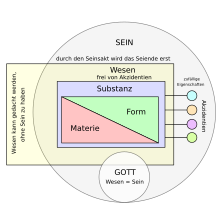

The concept of being in Thomas Aquinas can be presented as follows: A core element of the Thomistic ontology is the doctrine of the analogia entis . It says that the concept of being is not unambiguous, but analogous, that is, the word "being" has a different meaning, depending on which objects it is related to. Accordingly, everything that is has being and is through being, but it has being in different ways. In the highest and proper way it belongs only to God : he alone is his. All other being only has a part in being and according to its essence. In all created things, therefore, a distinction must be made between being ( essentia ) and existence ( existentia ) ; only with God do these coincide.

The distinction between substance and job is important for Thomas' system. It says: " Accidentis esse est inesse ", that is, "For an Akzidenz to be means to be in something". His “ Accidens non est ens sed entis ” goes in the same direction , ie “An accident is not a being , but something that belongs to something that is”.

Another important distinction is that of matter and form. Individual things arise from the fact that the matter is determined by the form (see hylemorphism ). The basic forms of space and time are inseparably attached to matter. The highest form is God as the cause (causa efficiens) and as the end purpose (causa finalis) of the world. The unformed primordial matter, that is, the first substance, is the materia prima .

In order to solve the problems connected with the development of things, Thomas falls back on Aristotle's terms act and potency . Because there is no (substantial) change in God, he is actus purus , ie “pure reality”.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel assumes that in the cognitive process, thinking only experiences its determination in relation to the object and is thus in contrast to Immanuel Kant , who sees thinking independently of the object of knowledge. Thought and object are no longer independent entities . In this sense, Hegel combines the realistic and constructivist ontology.

Edmund Husserl

Edmund Husserl speaks in his ideas about a pure phenomenology and phenomenological philosophy ( also Ideas I) of noesis and noema as basic moments of the constitution of the object and thus as the limit of what can be said ( see also Ludwig Wittgenstein ). So is z. B. the noema of the perception of a tree the “tree perceived”. But this differs fundamentally from the tree that z. B. can burn, while tree perception cannot because it has no real properties. However, the perception of the tree has its own objective meaning: z. B. trees can grow, must be touched, etc. The tree is thus understood as something that is structured in this way. We something as something vermeinen , is the central idea Husserl called intentionality .

The material (Greek: hyle ) of our perception is only through the intentional act as z. B. real, fantasized, dreamed, etc. meant. Which means we make sense of the hyle. Now after Husserl z. B. the subjects of biology also attached a sense, z. B. "moves by itself and reproduces". The meaningfulness behind it is the so-called material ontology , which Husserl also calls regional ontology . According to Husserl, these regional ontologies are the basis for the sciences , since they first constitute the object sense of the subjects of the individual sciences.

Nicolai Hartmann

Hartmann tries a new beginning of the ontology through a strict empirical basis. He thus rejects ontology as a doctrine of essence (see Husserl) and renounces any metaphysical claim. Unlike traditional ontology in the essentia saw the shaping force of the things he takes the empirical knowledge as a basis, which in a sense of reality reads the structures. Hartmann hereby takes a realistic position. It's about grasping something that exists before and independently of a knowledge . Hartmann distinguishes between two modes of being: real being and ideal being. Real being is again divided into four layers of being or levels: the psychic-material, the organic, the soul and the spiritual, which cannot be traced back to any of the lower levels. Ideal His are, at Hartmann. B. mathematical forms and ethical values. Nicolai Hartmann's ontological layer model comes under fire at the point where he speaks of the unintelligible rest . What is meant by this is the complexity of the world that cannot be fully explained. In doing so, however, he blocks any possible monistic solution.

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger's work is largely determined by the question of the meaning of being , i.e. the question of what we mean when we say “I am, it is, etc”, especially in his first major work, Sein und Zeit . According to Heidegger, the question of the “meaning of being” has been forgotten even in the history of metaphysics (oblivion of being ). Although Aristotle provided a categorization of the various regions of being of beings in his metaphysics by distinguishing the independent substance from the dependent accident , he did not ask the question of the meaning of being itself. Here Heidegger sees the reason why the question of the meaning of being has moved behind the question of being. In his opinion, this topic runs through the entire history of philosophy ( see also ontological difference ).

Heidegger now counteracts this with his fundamental ontology . Heidegger's approach is intended to pose this question anew. However, in order to ask this question (according to his analysis of the question structure in Being and Time ), one respondent must be considered in addition to what is asked and what is asked. The respondent is selected so that there could also be the answer. The only being, however, who can ask and answer this question at all, is the human being, "the being whose being is about its being itself" (so in being and time ). Heidegger defends himself against the accusation that his approach is an anthropology : he wants to clarify the meaning of being through the passage through questioning people.

Heidegger, for his part, will accuse Jean-Paul Sartre .

Jean Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre's main work, Being and Nothing, has the subtitle “An attempt at a phenomenological ontology”. The subtitle shows the work's claim to combine phenomenology and ontology. Sartre's approach is characterized by a "regressive analysis", which is based on the phenomenological consideration of individual phenomena , e.g. B. language , fear , freedom etc. about their general, underlying necessary structures asks: What must a person be that he can be afraid? Basically, the consideration in Being and Nothing is the representation of complex human structures, as an expression of a being that has a special relation to nothing , hence the name of the work. Sartre distinguishes here between human being , as a being that is not what it is and that is what it is not (being for itself) and being that is what it is (being in itself) . The impressive aspect of this thinking for the anthropological view of man is that Sartre does not think of man as a composition of different actions or properties, but as a totality : every action, every movement is an expression of a whole, leads back to a whole and reveals that Totality of the being of the individual.

Ernst Bloch

Based on the processual nature of matter (cf. also Hegel ), the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch developed an ontology of not-yet-being . For him, being is the fulfillment of the essence of being, its coming to itself, whereby this self is not already established in advance, but must first be "processed". The fulfillment of a unity of beings with their inner being, their being, is still pending. It is only indirectly present in the present as a utopian “foreshadow” and tendency and appears as “not yet conscious”. So being is always just not-yet, that is, always directed towards a future of fulfillment, which is the cause of becoming in general. Matter is “matter forward” because it pushes for “full being”. Bloch always understands this full being historically and materialistically as the “ Golden Age ”, which is a communist age in the broadest sense .

Analytical ontology

Ontology issues are also dealt with by analytically trained philosophers. In the initial phase of the analytical ontology , the approach was mostly followed to capture general structures of reality by means of language analysis. In the last few decades, the analytic ontology pursues all questions that are directly related to the structures and general properties of reality, without being bound by certain restrictions such as the linguistic analytical methodology. The topics of recent analytical ontology largely include the classical topics. Among other things, they include the basic categories , that is, such general terms as thing , property or event ; also terms such as part and whole or (in) dependent , which are attributes of certain entities. For example, it is discussed how the different categories relate to one another and whether a category can be characterized as fundamental. Are individual things mere bundles of properties ? Can there be general ideas or properties ( universals ) that exist independently of things? Do you need a separate category of the event?

In analytic philosophy, ontology is the theory of knowledge (epistemology) opposed. Among other things, this makes it possible to clarify ontological questions without making a preliminary decision about whether the ontology describes “the world” as it is “in itself”, or just how it appears to us or is described in our theories. Sometimes a strict separation between ontology and epistemology is also criticized.

Willard Van Orman Quine is a representative of the analytical tradition and has dealt particularly with the problem of the question of the identity conditions for entities of the various categories. The question is: How are copies A and B of category X identical or when are they different? Quine's answer to this is the famous saying “No entity without identity”. The view is expressed here that if one accepts an entity, one must also be able to say when specimens of this type are also identical.

Besides Quine resulted in his essay " What is it " the notion of "ontological commitment" (ontological commitment) and coined in this context the slogan "His is the value of a bound variable to be". The ontological obligations that assertions entail are the objects that must be accepted if they are true. According to Quine, however, everyday language statements occasionally contain misleading references to alleged entities. This becomes clear with the statement " Pegasus does not exist". It seems that Pegasus must already exist here in a certain sense, so that its existence can be denied. According to Quine, the actual ontological obligations only become apparent when such deceptive object references have been erased through a transfer to the "canonical notation" of predicate logic .

Individual evidence

- ^ KrV - Preface to the first edition

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: Declaration in relation to Fichte's science theory ( Memento of May 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). Allgemeine Literatur Zeitung (Jena), Intellektivenblatt No. 109. August 28, 1799, pp. 876–878.

- ↑ Luciano De Crescenzo : History of Greek Philosophy. The pre-Socratics. Diogenes, Zurich 1 1985, ISBN 3-257 01703-0 ; Page 113

- ↑ Parmenides, fr. 6, Nestle

- ^ Pseudo-Plutarch: Stromata , 5

- ^ Critical to Quine: Hans Johann Glock: Does ontology exist? (PDF; 226 kB) Philosophy, 77 (2/2002), 235–256, German: Ontology - Does that really exist? (PDF; 47 kB), in: P. Burger and W. Löffler (eds.): Meta-Ontologie, Mentis, Paderborn 2003, 436–447