Monadology

The monadology (from the Greek μονάς monás “one”, “unity”) is the monad theory founded by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and the title of the work from 1714, in which he explains it in 90 paragraphs. The monadology explained there is the doctrine of monads or simple substances or ultimate elements of reality and is the core of Leibniz's philosophy that serves to solve metaphysical problems.

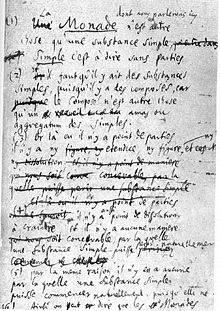

It should be noted that the work does not provide a comprehensive account of Leibniz's philosophical system as such and as such was not intended for publication by him. Rather, Leibniz wrote the text with the aim of presenting the metaphysical component of his philosophical system to the scholars around the French Platonist Nicolas François Rémond . Leibniz sent the text to Rémond in July 1714 under the title Eclaircissement sur les Monades . The German title Monadologie was chosen by Heinrich Köhler in his first translation into German from 1720.

content

The primordial monad is God; all other monads are their products; they can only be destroyed or created by God and cannot arise or perish by themselves. The world consists of aggregates of many monads, all of which are different from one another and yet act autonomously as entelechies insofar as they have an appetite (from French appétitions , often also translated as desires ) for and the ability to perceive (principle of plurality in the unit). Leibniz understands “perception” to be the mere process of continuous perception itself. Perceptions cannot in principle be explained by mere mechanical reasons : even if one could build a machine that was capable of perception and that one could step on, one would only bump into one another inside Find parts, but never an explanation for a perception. Such a machine resembles a mill: "Assuming this, one will find nothing else when inspecting the interior than several engines, one of which moves the other, but nothing at all that would be sufficient to give the basis of any idea."

Every plant, every mineral, even every particle of matter (down to the infinitely small, the monad itself) is a body with (contingently) associated monad, each with different degrees of unconscious ideas (the standard by which all monads are different from one another); Monads as animal souls have sensation and memory. The human soul (spirit) is also a monad and differs from animals only insofar as it is gifted with reason (qua principle of sufficient reason and principle of contradiction ). In addition to the perceptions and appetites in the human soul, there is also apperception - self-perception or self-awareness - and insight into the necessary and eternal truths, with which a possible idea of God himself is connected (Leibniz also connects this with a disposition of people (or . Spirits) for social union in the moral world of the God-state).

Each monad revolves within itself - nothing comes out of it and nothing into it: They “[…] have no windows through which anything can enter or exit”, which is why they cannot have any effect on one another, although they can each for themselves "[...] are an everlasting living mirror of the universe". Each monad expresses the whole world from its perspective like a living mirror, depending on its level of being. However, with the exception of God, who ensured complete proportionality, she never fully perceives the universe with all clarity, since she always presents the body belonging to her more clearly than the rest.

The connection of the monads is guaranteed by the pre-stabilized harmony , which ensures that God harmonizes the perfection of the monads (as it were from the beginning of things and for all time), and from which their effect on each other and their strength is derived: the more perfect a creature is, the more reasons there are a priori , by its nature , that it should affect another creature. According to this principle, the processes of all monads are synchronized with one another: they are active insofar as they have clear perceptions, and they suffer insofar as they have confused perceptions.

Only God has adequate and completely objective monadological ideas, since he, as the highest and absolutely perfect substance ("original unity" or "original substance"), also has the highest degree of reality in him, which is not limited by anything. God is also the only power that determines the being of the monads: Since monads, due to their simplicity, are not subject to the natural arising and decay of bodies composed of parts, they can only arise through creation and only perish through annihilation.

expenditure

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Doctrinal propositions about monadology, the same of God and his existence, his characteristics and the soul of man etc. as well as his last defense of his Systematis Harmoniae praestabilitae against the objections of Mr. Bayle . Translated from the French by Heinrich Köhler. Meyer's blessed widow bookstore in Jena, Frankfurt and Leipzig 1720.

- GW Leibniz: Monadology (French / German). Translated and edited by Hartmut Hecht, Reclam, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-15-007853-9 .

- Nicholas Rescher: GW Leibniz's Monadology. An Edition for Students . Pittsburgh 1991, ISBN 0-8229-5449-4 (French text, English translation, parallel passages in other works and commentary).

Single receipts

- ↑ See P. Prechtl (Ed.): Philosophy . Metzler compact, Stuttgart 2005, p. 121.

- ^ Hubertus Busche: Introduction . In: Hubertus Busche (ed.): Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Monadology . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2009, pp. 1–35, here: p. 3.

- ^ Hubertus Busche: Introduction . In: Hubertus Busche (ed.): Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Monadology . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2009, pp. 1–35, here: pp. 3f.

- ↑ Franz-Peter Burkard, Franz Wiedmann: dtv-Atlas for philosophy: tables and texts . German Taschenbuch-Verlag, 1991, ISBN 978-3-423-03229-2 , pp. 113 .

- ^ Robert von Zimmermann (commentary and translation): Monadologie. German with a treatise on Leibnitz and Herbart's theories of what actually happened. Braumüller & Seidel, Vienna 1847, IX, § 17, p. 15; French: "Et cela posé, on ne trouvera, en le visitant au dedans que des pieces qui se poussent les unes les autres, et jamais de quoy expliquer une perception." In: Monadologie (Édition Gerhardt, 1885) , IX, § 17

literature

- William E. Abraham: Monads and the Empirical World . In: Studia Leibnitiana Supplementa , No. 21, 1980, pp. 183-99.

- Johannes Bronisch: The patron of the Enlightenment. Ernst Christoph von Manteuffel and the network of Wolffianism. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2010 (early modern period 147) (especially pp. 232–305: Wolffianism and Manteuffel in the monad dispute 1746–1748 ).

- John Earman: Perceptions and Relations in the Monadology . In: Studia Leibnitiana . No. 9, 1977, pp. 212-30.

- Montgomery Furth: Monadology . In: Philosophical Review . No. 76, 1967, pp. 169-200; Reprinted in HG Frankfurt (ed.): Leibniz. A Collection of Critical Essays . University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame 1976.

- Jürgen Mittelstraß : Monad and Concept . In: Studia Leibnitiana . No. 2, 1970, pp. 171-200.

- Fabrizio Monadori: Solipsistic Perception in a World of Monads . In: M. Hooker (Ed.): Leibniz. Critical and Interpretive Essays , Minneapolis 1982, pp. 21-44.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Monadology . In: Hubertus Busche (Ed.): Interpret classics . tape 34 . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004336-4 (contains works in German and English).

Web links

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Monadology, translated and introduced by Robert Zimmermann, Vienna 1847 in Project Gutenberg ( currently not available to users from Germany )

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Monadology. Translated by Heinrich Köhler. Frankfurt am Main, 1996.

- George MacDonald Ross: The Monadology. Index. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012 ; Retrieved January 5, 2016 . (Subject index and English commentary).

- Research bibliography (until 2003).