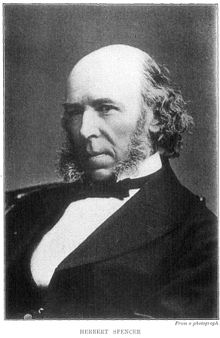

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (born April 27, 1820 in Derby , † December 8, 1903 in Brighton ) was an English philosopher and sociologist . He was the first to apply the theory of evolution (here: the concept of the “survival of the fittest” ) to social development, thereby establishing the paradigm of evolutionism , which is often viewed as the forerunner of social Darwinism .

Life

After his education, which he received largely at home, Spencer worked from 1837 to 1846 at the London and Birmingham Railway as a railway engineer (draftsman), assistant teacher and from 1848 to 1853 as an editor for the Economist and freelance writer. Within the Chartist movement he was involved in the struggle for universal suffrage. The death of his uncle Thomas Spencer in 1853 and the inheritance that came with it allowed Spencer to quit his post and live as a freelance writer.

As a sociologist and philosopher, Spencer was self-taught . He mainly read scientific texts ( Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck , William Benjamin Carpenter ) and applied the ideas gained there to society. In his writings he insisted on the application of (natural) scientific methodology and knowledge for philosophical investigations.

Politically, Spencer was firmly rooted in classical liberalism , which was particularly reflected in his later work. Spencer tried to unite the entire knowledge of his time in a "system of synthetic philosophy".

Work and effect

Like Claude Henri de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon , Auguste Comte or Karl Marx , Spencer was looking for an explanation of social change or the stages of development of a society . Impressed by Lamarck's theses, he applied them to social systems for the first time in Social Statics (1851). Lamarck postulated that the evolution of living beings takes place due to external factors, while the common social-scientific paradigm of that time, positivism , explained society only in terms of social factors. In Social Statics, Spencer describes society as a “superorganism” with organs that follow Lamarck's laws of growth and decline. In Der Soziale Organismus (1860) he worked out these ideas.

Spencer began his life's work around 1860: the synthesis of all human knowledge, based on an omnipresent principle that works in all living things: evolution . According to Spencer, only the laws of evolution allow the structuring and integration of empirical data from all physical, social and psychological areas of science under one principle; therefore evolutionism represents the first scientifically founded world view. As an enthusiastic supporter of Darwinism, he believed that he could apply the principle of evolution in all sciences and thereby unite them into a "system of synthetic philosophy". Spencer was convinced that in the self-organizing genesis of things he had found an important key to understanding them. The starting point that things develop in the world without divine (or other) guidance and that something “more complex” or “higher” emerges from “simple” was revolutionary for its time. Like John Stuart Mill , Spencer professed strict empiricism ; with Immanuel Kant he made a categorical distinction between phenomena, but he attributed an inherent power to the objects of experience, which he saw as a manifestation of the "unfathomable". Scientific knowledge therefore only differs from everyday life through a particularly precise description of the world of experience and through the discovery of universal laws within the scientific disciplines.

After reading Carpenter, Spencer adopted his theses in his First Principles (1860) and postulated that in the social sphere, too, all things develop from homogeneous to heterogeneous. He justified his “universal postulate of cultural evolution” by deduction: not only biological organisms, but also education, ways of life, social conventions, psychology, politics, etc. would follow this law, without “divine” or other influence from outside (First Principles, 1862). On one point Spencer was in line with his positivist contemporaries (e.g. Comte): They too saw the development of sociology embedded in a broad development or reorganization of all scientific disciplines on the one hand and an equal, all-pervasive law on the other.

Finally, in his further principles, Spencer developed a general philosophy based on the various previously developed theories of evolution: The entire universe functions like a gigantic organism, the ever increasing specialization and differentiation leads over time to an ever more harmonious coordination of the individual components. Like Comte before, Spencer noticed the same development not only for the whole, but within each individual component. In the Principles of Biology (1864–67) Spencer integrated the theories of Charles Darwin , Alfred Russel Wallace , but also Henri Milne Edwards on the division of labor in organisms.

As a sociologist and evolutionist, Spencer is considered by some to be the founder of social Darwinism . He popularized the term evolution for social development, just as he (and not Charles Darwin) coined the term “survival of the fittest” (see evolution theory ), where he coined Darwin's “natural selection” for “struggle about existence ”.

According to Spencer, social development is similar to that of a biological organism. Controlled by the invisible hand of evolution, what will prevail over the long term is what best contributes to the survival of the organism. In this process stands the non-conformist, i.e. H. the socially weaker, the progress of society in the way. Spencer saw India's “Eurasians” as an example of “degeneration” as a result of ethnic mix and wished that inter-ethnic marriages would be “decidedly forbidden”.

Unlike later Social Darwinists, Spencer was firmly rooted in liberalism. Based on his Protestant ethics , he postulated the Law of Equal Freedom (LEF) that a person has every freedom as long as he does not interfere with the freedom of another. For these ethical reasons as well as because they contradicted the logic of evolution, Spencer opposed any intervention by the state in human society. In his most political work, The Man Versus the State , he consequently went so far as to demand the right of every individual to secession from the state.

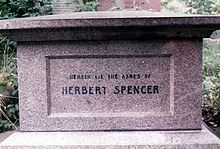

According to his last will, Spencer was cremated in Golders Green Crematorium , and his tomb is near that of Karl Marx in London's Highgate Cemetery .

literature

Primary literature

- Social Statics (1851)

- System of Synthetic Philosophy (1860)

- The Social Organism (1860)

- Education (1861)

- First Principles (published in 6 parts 1860-62)

- Principles of Biology (1864-67)

- Principles of Psychology (1870-72)

- Principles of Sociology (1874, ISBN 0-7658-0750-5 ) (German: The Principles of Sociology 1877 B. Vetter Volume 1–4)

- German explanation: The principles of sociology . (2001). Kellermann PS 468-471 ISBN 3-531-13235-0 . also: Jolandos Verlag, ISBN 3-936679-52-5

- Principles of Ethics (1879-93)

- Review by Samuel Alexander . Mind (NS) 2 (1893), 102-110

- The Man 'versus' the State (1884)

- Autobiography (1904)

Secondary literature

- Wolfram Forneck: The inheritance of individually acquired traits . Depicted at the dispute between August Weismann and Herbert Spencer. 2nd Edition. BoD - Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2014, ISBN 978-3-7357-9153-5 .

- Otto Gaupp: Herbert Spencer. Frommanns 1897.

- August Stadler: Herbert Spencer - Spencer's Ethics - Schopenhauer. R. Voigtländers Verlag Leipzig 1913.

- David Duncan: Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer. (2 volumes), University Press of the Pacific, 2002.

- Johann G. Muhri: Norms of education. Analysis and criticism of Herbert Spencer's evolutionist pedagogy . 1982. ISBN 3-7705-2065-3

- WC Owen: The Economics of Herbert Spencer . 2002, ISBN 1-4102-0004-3 .

- Uwe Krähnke: Herbert Spencer . In: Ditmar Brock, Uwe Krähnke / Matthias Junge: Sociological theories from Auguste Comte to Talcott Parsons 2nd edition, Munich: Oldenbourg 2007. Pages 79–98.

Web links

- Literature by and about Herbert Spencer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Herbert Spencer in the German Digital Library

- David Weinstein: Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Herbert Spencer . In: The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Michael Beetz: The unpleasant system. Herbert Spencer's work as a prototype of a universal theory ZfS 2010, pp. 22–37

Individual evidence

- ↑ David Duncon (ed), Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer, New York in 1908, II, p 16F; Spencer's letter of August 26, 1892 to Kentaro Kaneko.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Spencer, Herbert |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English philosopher and sociologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 27, 1820 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Derby |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 8, 1903 |

| Place of death | Brighton |