Eschatology

Eschatology [ ɛsça- ] (from ancient Greek τὰ ἔσχατα ta és-chata 'the outermost things', 'the last things' and λόγος lógos 'teaching') is a theological term that describes the prophetic doctrine of the hopes for the perfection of the individual (individual Eschatology) and all of creation (universal eschatology) . This is also understood to mean the doctrine of the so-called ultimate things and, connected with it, the "doctrine of the dawn of a new world".

The term was originally coined in Lutheran Protestantism and, after its acceptance as a description for certain contents, was also transferred to other religions. Eschatological ideas can also be found in ancient Iranian religions (in the Avesta , in Zarathustra ) and in Islam .

Concept history

The word eschatology goes back to the Lutheran theologian Abraham Calov , who first used it in the 17th century as a name for the final part of his dogmatics. What was meant were the things that will finally happen in the "framework of the historical development directed by God". This designation prevailed until the 19th century. This word is linked to a passage from the deuterocanonical book Jesus Sirach ( Sir 7.36 EU ): “Whatever you do, think of your end (in the Greek Septuagint τὰ ἔσχατα σου and in the Latin Vulgate novissima tua ), then you will never do anything bad ”. Accordingly, the two terms eschatology and de novissimis can be found for the last section of a dogmatics.

Judaism

Tanakh

In Old Testament science, the term eschatology can refer, on the one hand, to prophetic announcements and, on the other hand, to the notions of the end of the world or history. Often, however, a combination of both terms is attempted and eschatology is understood as the idea of an inner-worldly salvation time. So the end of all things is not expected, but a fundamental change in circumstances and thus a completion of creation. Both present and futuristic eschatological notions can be found in the Old Testament.

Presentational ideas go back above all to the Jerusalem cult tradition and can be found in the Psalms . This is linked to a Zion theology that understands Mount Zion as the navel of the world and as the point at which God is closest to people. YHWH protects the people in Jerusalem from calamity and thus ensures a flourishing city in the vicinity of this mountain.

Futuric eschatology can be found above all in the books of the prophets and in the history books: The prophets of the pre-exilic period also proclaimed hope for an eschatological salvation time. This dispensation is emphasized even more strongly by the post-exilic prophets. If a positive but realistic future is portrayed in the pre-exilic period, Deutero-Isaiah, for example, depicts “a wonderful event with universalistic dimensions” in the exile period .

Judaism in the time of Jesus

In the Jewish eschatology at the time of Jesus one differentiates between two basic types already visible in the Tanach :

- The national-this-side hope for the liberation of Israel. Here the Old Testament prophetic announcement of salvation is continued.

- The universal apocalyptic expectation of the end of the world, the resurrection of the dead and judgment, combined with the hope of a world to come.

However, these two basic types were not strictly separated: Apocalyptic also speaks above all of the future of the nation of Israel, and the term “Messiah”, the earthly liberator, is sometimes also applied to the transcendent Savior. The apocalyptic thought of the general resurrection of the dead is sometimes linked with the prophetic thought of the “remainder”: Only this one will be preserved in judgment and will experience God's new world.

The apocalyptist sees his teaching as consolation : In a time of great need, he points out that current events correspond to God's will and that the end is near. In addition, the apocalyptic announces a “ compensatory justice ”: God will transform the present sufferings into joy in the coming new world, and the now apparently triumphant enemy will then be destroyed. The idea of hope is strongly spiritualized and individualized in Jewish apocalyptic : salvation is no longer expected from the inner historical future, but from the hereafter . The individualization of piety is a general characteristic of Judaism in the New Testament period.

Christian eschatology

New Testament eschatology

The New Testament eschatology takes its starting point in the announcement of Jesus that the reign of God has come near ( Mk 1.15 EU ) and at the same time is already present in his actions ( Luke 11.20 EU , Matt 12.28 EU , Matt 11.15 EU , Lk 7.22 EU ).

The apostle Paul of Tarsus provides the first evidence for the question of the ultimate things after life and death in his letters.

Paul lived in the expectation of the imminent return of Jesus and hoped for his return while he was still alive. Even so, that security was tested by those who died in the churches before the Christ came, and doctrinal adjustments became necessary. He takes up this new situation in the teaching that all believers share in Christ, so that through God the “inescapable deathly ruin” of all people was lifted. A second change is made in relation to the question of how to participate in the kingdom of God. If it is initially the case that this happens through the rapture, when dealing with the situation in Thessaloniki it is admitted in the first letter to the local church that the dead believers will also have a share in this kingdom.

The life and fortune of Christians is also shaped by eschatology, so that Paul assumes an “eschatological existence” so that present sufferings can be endured, in the certainty that God will raise the living from the dead. As an example of this endurance, the apostle repeatedly cites himself as an example.

The Evangelist John emphasizes the present in his eschatological considerations, however not in the sense of a present eschatology, but in the sense of a reinterpretation of the temporal: Since the representation itself, measured against the point in time of what is represented, lies in the future, there is always a double perspective of the present "Faith does not suspend time, but gives it a new quality and direction." Baptism ensures that the heavenly Paraclete is also present in the church after the death of Jesus and in the imitated baptism of the believer the new birth takes place in Jesus. In addition, however, there is an emphasis on the futuristic eschatology, for example in Jn 5:25 Lut "Amen, amen, I tell you: the hour is coming and it is already there." In this future, what has already been announced and announced in the present will become apparent is decided: The resurrection from the dead.

Old church tradition

In the old church, the Christ event was accordingly related to the fulfillment of the Old Testament promise of salvation and Jesus was understood as the new covenant and his resurrection as a forerunner for the general resurrection of the dead.

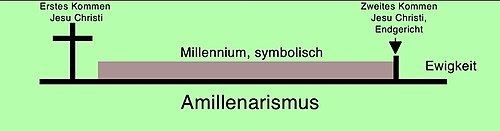

Augustine of Hippo , probably the most influential theologian of the old church, turned against the imperial christology , which was often advocated in the 4th century , according to which eschatology begins with a realized but still secular state (see amillennialism ). An example of this is Eusebius of Caesarea , who saw the Constantinian turning point as the starting point for this eschatology. He criticized the synthesis of the Roman Empire and the Christian Church and thereby emphasized the difference between the earthly existence of the Christian and the hope of a salvation perfection on the other side.

Another important feature is the demarcation from universal reconciliation , for example according to the teaching of Origen , and instead the assertion of an eternity of hell punishments for sinners.

middle Ages

The Middle Ages were shaped by Augustine's eschatology: On the one hand, there was tension between one's own existence as a sinful Christian and the hope for the hereafter perfection of salvation and other elements of Augustine's teaching.

A new addition was the doctrine of purgatory as a way of clarifying the question of what happens to the individual between the individual death and the return of Christ. Another question discussed was whether the souls of the deceased could be saved before the Last Judgment or whether this happened afterwards. Pope John XXII. claimed a differentiation, while Pope Benedict XII. , his immediate successor, asserted an identity of divine vision in the intermediate area and after the Last Judgment.

Reformatory eschatology

On the one hand, the Reformation theologians continued the existing tradition and also emphasized the futuristic eschatology; on the other hand, they also broke with the existing teachings in two cases:

On the one hand, instead of the individualization of eschatology, they emphasized their own doctrine of justification , according to which the salvation of all depends only on Christ. Accordingly, the crediting of human works was disputed before the last court. For this reason, purgatory was initially criticized because it was viewed as unbiblical on the one hand and as a reason for the indulgence trade on the other .

Second, the present eschatology was emphasized more strongly, that is, there was an emphasis on "the presence of eschatological divine salvation in faith."

Debates about eschatology in modern times

Protestantism

After the Reformation and based on it, there were various debates about the nature of the eschatological return of Jesus. At first, Protestant theology split over the question of whether eschatology should be understood in the sense of a premillenarianism or in the sense of a postmillenarianism . The first determination insists that Jesus will come to earth before the thousand-year kingdom, while the second determination claims that this will not happen until after the thousand years. In the time before, instead, his work should take place in the power of the spirit. This work can be recognized by the fact that the sermons work or that contemporary Christianity is improving. The Pietists are an example of the representatives of postmillenarianism .

In the 19th century the cultural Protestant reading of Protestantism gained influence. The theology from this tradition emphasized above all a reading of the kingdom of God as a religious and moral community, that is, based on love for God and neighbor. Albrecht Ritschl emphasized in particular the necessary “work on the kingdom of God” in the earthly world as a task for Christians. This made eschatology intrinsic to history and thus ignored elements of older traditions that were transcendent in history.

Criticism of such an understanding was first expressed by Johannes Weiß , who emphasized that the biblical representations of the teaching of Jesus precisely exclude a human share in the kingdom of God. This criticism became louder after the First World War , so that this eschatology aimed at ethics was no longer received. Rudolf Bultmann accordingly emphasized a present kingdom of God and saw himself in the tradition of Paul and John. "History in the sense of a temporal course of events is not of interest theologically, but only the historicity of human existence that appears in the eschatological now."

A renewal of a futuristic eschatology happened through the book Theologie der Hoffnung by Jürgen Moltmann (* 1926), who sees eschatology as a topic of the future, and this future is always Christologically qualified for him.

The Anglican Nicholas Thomas Wright (* 1948) tries to trace the New Testament and early Christianity, which were initially shaped by a proximity to Jewish-Pharisaic ideas. But again, the resurrection of Jesus Christ anticipates the general resurrection. He refutes the popular notion that Christianity is only about “going to heaven after one has died.” On the other hand, central is the kingdom of God that has already come to earth, in which God became King on earth as in heaven, which has often been ignored by the churches. It is about God's action, who has reconciled this world with himself and will not end it “on the last day”, but will transform it. It is the task of the church to already now fragmentarily live out this ultimate transformative action of God.

Non-religious references

In his writings, the Catholic theologian Kurt Anglet makes eschatological references between the New Testament and the works of greats in literature , music and political theory . The book The End by the philosopher and neuroscientist Phil Torres deals with the cultural effects of Western eschatologies and problematizes them in the prevention of existential risks such as climate change .

Islam

Eschatology in Islam is the doctrine of 'the last things' at the end of days . Concepts about life after death are found in the earliest suras of the Koran and are further elaborated by both Muslim commentators and Western Islamic studies . Hadith and later Islamic theologians and philosophers such as al-Ghazālī , al-Qurtubi , as-Suyuti or al-Tirmidhi deal with eschatology under the keyword maʿād (معاد 'return'), a word that appears only once in the Koran and is also often used in place of resurrection .

See also

- Salvation history

- Millenarianism , premillenarianism , amillennialism

- Messiah

- End time

- Chiliasm

- Parousia

- Near death experience

- All-death theory

- Letter from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on some eschatological issues

- Mahdi

literature

- Edmund Arens (Ed.): Thinking Time. Eschatology in an interdisciplinary discourse. Freiburg i. Br. 2010, ISBN 978-3-451-02234-0 .

- Lothar Gassmann: What's to come. Eschatology in the 3rd millennium. Wuppertal 2002, ISBN 3-87857-313-8 .

- Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : “The end is near!” The mistakes of the end-time specialists (theological teaching and study material; 24). 3. Edition. Verlag für Kultur und Wissenschaft, Bonn 2007, pp. 99–137: "How should we really deal with the biblical end-time statements?"

- Dieter Hattrup : eschatology. Paderborn 1992.

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Marquardt : What can we hope when we can hope? An eschatology. Volume 1. Kaiser, Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn, Gütersloh 1993, 482 pages, ISBN 3-579-01925-2 ; Volume 2 Gütersloh 1994, 415 pages, ISBN 3-579-01945-7 ; Volume 3 Gütersloh 1996, 564 pages, ISBN 3-579-01946-5 .

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Marquardt: Eia, if we were there - a theological utopia. Gütersloh 1997, ISBN 3-579-01947-3 .

- Jürgen Moltmann : The coming of God. Christian eschatology . Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-579-02006-4 .

- Jürgen Moltmann: Theology of Hope . Investigations into the justification and consequences of a Christian eschatology. Gütersloh 2005, ISBN 3-579-05224-1 .

- Markus Mühling: Basic information eschatology. Systematic theology from the perspective of hope. Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8252-2918-4 (textbook from a Protestant perspective).

- Joseph Ratzinger : eschatology - death and eternal life. 2nd edition, Pustet Verlag, Regensburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-7917-2070-8 .

- Marius Reiser : The Last Things in the Light of the New Testament. Patrimonium-Verlag , Heimbach / Eifel 2013, ISBN 3-86417-018-4 .

- Walter Simonis : Resurrection and Eternal Life? The Real Origin of the Easter Faith. Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-70345-X .

- Michael Stickelbroeck : After death. Heaven - Hell - Purgatory. Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-936484-33-3 .

- Jacob Taubes : Occidental Eschatology. Bern 1947 (last Munich 1991, ISBN 3-88221-256-X ).

- Hans Wißmann, Rudolf Smend a. a .: Eschatology I. Religious history II. Old Testament III. Judaism IV. New Testament V. Old Church VI. Middle Ages VII. Reformation and Modern Times VIII. Systematic-theological. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . 10: 254-363 (1982). (Good, comprehensive overview from experts in the respective sub-area)

- Nicholas Thomas Wright: Surprised with Hope: What the Bible Really Says about Resurrection and Eternal Life. Sowing, Neukirchen 2011, ISBN 3-7615-5842-2 ; 2nd edition 2017.

Web links

- Current literature on eschatology (private site)

- Klaus Koenen: Eschatology (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Christian Wetz: Eschatology (NT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

Individual evidence

- ^ Geo Widengren : eschatology. In: Iranian Spiritual World. Holle Verlag, Baden-Baden 1961, pp. 165–248.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt : Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition, Göttingen 2009, p. 388.

- ^ Klaus Koenen: eschatology (AT). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- ^ Hans Conzelmann , Andreas Lindemann: Arbeitsbuch zum New Testament. 10th edition, Tübingen 1991, pp. 183–185 (§ 19: Das Judentum , chapter 5).

- ^ Hans Conzelmann, Andreas Lindemann: Arbeitsbuch zum New Testament. Tübingen 1991, pp. 184f.

- ↑ Udo Schnelle : Theology of the New Testament. 2nd edition, Göttingen 2014, pp. 316–317.

- ↑ Udo Schnelle: Theology of the New Testament. 2nd edition, Göttingen 2014, p. 320.

- ↑ Udo Schnelle: Theology of the New Testament. 2nd edition, Göttingen 2014, p. 319.

- ↑ a b Udo Schnelle: Theology of the New Testament. 2nd Edition. Göttingen 2014, p. 703.

- ↑ Udo Schnelle: Theology of the New Testament. 2nd Edition. Göttingen 2014, p. 704.

- ↑ Udo Schnelle: Theology of the New Testament. 2nd Edition. Göttingen 2014, p. 707.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 389.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 391.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 393.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 396.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 400.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 401.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 406.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 408.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 409.

- ^ A b Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition, Göttingen 2009, p. 410.

- ^ Rochus Leonhardt: Basic Information Dogmatics. 4th edition. Göttingen 2009, p. 411.

- ↑ Jürgen Moltmann: The coming of God. Christian eschatology . Gütersloh 1995, p. 109 f .

- ^ Nicholas Thomas Wright: Surprised by Hope, Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection and the Mission of the Church , New York 2008, pp. 31-230.

- ↑ Phil Torres: The End. What Science and Religion Tell Us about the Apocalypse . Pitchstone Publishing, Durham (NC) 2016, ISBN 978-1-63431-040-6 , pp. 288 (English).

- ↑ Jane I. Smith: Eschatology. In: Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān. Volume 2, Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, ISBN 9789004120358 .