Psychopathography Caspar David Friedrichs

The Psychopathographie Caspar David Friedrich assessed the personality and work of the painter of the Romantic and concentrates on his alleged mental illness . Already during Caspar David Friedrich's lifetime there was a widespread opinion that his otherworldly motifs and gloomy stylistics could only be the mirror of a sick soul. The reasons for this are preferably sought in his biography. Friedrich's pathography is described in a multidisciplinary manner from a humanities and medical-psychiatric perspective with different criteria. While art historians use psychological categories very generally, psychiatrists use the classification of mental illnesses as a guide. Friedrich's fate is considered to be an example of the “psychography of the epoch” of Romanticism, in which melancholy shaped the artist's relationship to himself and the world. Even under the conditions of modern therapeutic methods and the use of antidepressants , the painter would probably have refused therapeutic help because, according to the assumption, he wanted to go through his depression .

Problems of the pathography of Friedrich

For the interpretation of Friedrich's work, pathographic findings were used at all times as the key to understanding the sense of image and symbolism. The assessment of the painter's disease progression from an art-scientific, general medical, psychiatric or psychoanalytical perspective refers to a biographical material basis that does not allow any definite diagnostic conclusions. The traditions of Friedrich's personality and behavior contradict each other and are often mutually exclusive. The connections established between the clinical picture and the work usually relate one-sidedly to the symbolism of death and gloomy painting style, but not to an overall analysis of the painter's art production. A fundamental problem with pathography is that an inadequate scientific method has been developed for it. The academic discussion on pathography that had been going on since the second half of the 19th century was determined by the prevailing view of the world and man as well as the state of psychiatric science. Only modern operationalized diagnostics can systematize the traditions of Friedrich's clinical picture and critically evaluate the sources. Friedrich's pathography presents itself today as a condensation of multidisciplinary aspects. The painter's diagnosis of the illness must remain provisional, but it works out the connections in the disturbance dynamics more precisely. From the point of view of art history, pathography can make access to the work more difficult because it excludes the individual story of suffering from the context of Romanticism.

Contemporary findings

Friedrich's contemporaries noticed that the painter had a melancholy character with a tendency towards depressive moods. The most differentiated assessment at that time probably comes from Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert , who saw him as "a strange pair of moods".

“[...] for the deepest seriousness as well as for the most cheerful joke, such things are not infrequently found among the most excellent melancholics and comedians. Because that Friedrich was in the highest degree of melancholy temper, that everyone knew who knew him and his story, as well as the basic tone of his artistic work. "

The doctor Carl Gustav Carus , who was friends with Friedrich since 1817, is now considered the most accepted source for assessing Friedrich's clinical picture. He wrote in a letter to Johann Gottlob Regis on September 17, 1829 as well as in his memoirs about the illness-related alienation between himself and the painter.

"Friedrich has to write in detail about him, a thick, cloudy cloud of intellectually unclear conditions has been hanging over him for a few years, because they tempt him to grossly injustice against his own, whom I openly spoke out against him about, and have completely detached from him."

“In the city, the only difficulty that sometimes oppressed me at that time came from a few friends who had been very dear to me as people for a long time, but to whom the now ever advancing, always quietly changing and transforming life followed and after the situation had completely shifted [...] The first of these friends was Friedrich. In his peculiar, always dark and often hard disposition, apparently as a forerunner of a brain ailment to which he later suffered, certain fixed ideas had developed which began to completely undermine his domestic existence. Suspicious as he was, he tormented himself and his family with ideas of his wife's unfaithfulness that were completely out of thin air, but nevertheless sufficed to completely absorb him. Attacks of raw severity against his own are inevitable. I gave him the most serious ideas about it, also tried to act as a doctor, but everything in vain and so of course my relationship with him was disturbed as a result, I almost never came to him until later, after he was paralyzed by the stroke to still be useful to him to the best of his ability, but always lost a meaningful and valuable contact to me in every respect. "

Carus was a doctor researching in the field of psychology and published a highly regarded lecture on psychology which appeared in print in 1831. With Friedrich he held back in the diagnosis of his psychological conditions.

With knowledge of some of the thoughts of his friend in the painting Saul and David from 1807, Gerhard von Kügelgen gave the facial features of Frederick to King Saul, who was afflicted by the evil spirit in his dark thoughts and who took his own life in a hopeless situation.

Pathographies

- The first pathography from a medical point of view is presented in 1974 by Dieter Kerner in the short journal article Die Kranken by the painter Caspar David Friedrich . The internist tries to reconstruct the course of the disease on the basis of contemporary sources and carries out specific diagnostics using self-portraits and painter's motifs.

- In the compendium Insanity and Glory. The psychiatrists Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum and Wolfram Kurth assume the secret psychoses of the powerful in Friedrich from early “ psychosomatic forms of suffering” and classify the suffering as a “traumatic layer neurosis and psychosomatic disorders”. There are no differentiated comparative references to the painter's work here.

- In 2005, the art historian Birgit Dahlenburg, together with the psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carsten Spitzer, systematized the sources on pathography in Friedrich's work and texts, including the reports of contemporaries in relation to the painter's presumable episodes of illness in the study Major depression and stroke in Caspar David Friedrich .

- At the interdisciplinary symposium held in 2006 by the Berlin Psychoanalytical Karl Abraham Institute and the Pomeranian State Museum Greifswald , art historians, cultural scientists and psychoanalysts discussed the interplay between the impact of Friedrich's art and his biography from a psychoanalytic perspective.

- In 2006, the psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carsten Spitzer presented the first pathography on Friedrich, which critically illuminates the existing material base and points out methodological problem areas. He tries to assess the course of the disease on the basis of today's standards of operationalized diagnostics.

- The art historian Helmut Börsch-Supan draws in 2008 in the volume Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as a law for the first time after Friedrich's life crises on the basis of a detailed analysis of his pictures and developments in the entire work. He refers to the complexity of the painter's personality and the depth of his art.

- In his P-Book study published in 2014, the journalist Detlef Stapf brings Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts revealed a series of fundamentally new insights into Friedrich's work and biography, which represent a changed material basis for the painter's pathography. He discusses an oedipal conflict of the painter and art as a space for mental conflict management as well as the problem of self-worth in psychodynamics .

Childhood and loss experience

Contemporaries made the encounter with death in childhood responsible for Friedrich's melancholy mood, melancholy , withdrawnness and depression. The mother died when Caspar David was seven years old. He witnessed the early death of his siblings Maria (1791), Christoffer (1787) and Elisabeth (1782). Statements by the painter about the processing of these strokes of fate are not known. Several sources spread the story of the fatal accident of his brother Christoffer. Three years after Friedrich's death, the biographical essay by an anonymous author appeared in the Blätter für literary entertainment with a description of the event.

“It is said that life full of sinister seriousness had already chased him away from the soil of his homeland at an early stage. One day enjoying the icy pleasure of the Nordic winter on ice skates with a lovingly loved brother, Friedrich would have found himself on a not frozen part of the river, would have been overtaken by death, had his brother not been so happy, already half devoured by the breaking ice cover to help out again. But both forgot in the joy of being rescued that the unsteadiness of their luck cannot be trusted. Perhaps following your skid school more carefree than before, it is soon his brother's turn to sink into the collapsing ice cover and has already disappeared beneath it when Friedrich, screaming out loud, reaches out his arms to serve his brother in the same way as he does him proved just as such. The horror that gripped the lonely brother about it is said to have made it unbearable for him to stay at home after he had fought the first resolution not to survive the drowned man. "

This story was told in various ways and with different decorations by Carl Gustav Carus, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Wilhelmine Bardua and Count Athanasius von Raczynski . The core of the tradition is seldom questioned in art historical literature. There is criticism of the credibility of the anonymous text itself because it is highly unlikely that Friedrich, almost drowned in the ice-cold water, would continue his skating carelessly. Other sources are hardly considered. In the family of Gustav Adolf Friedrichs, nephew and godchild of Caspar Davids, the course of the accident was described differently. The siblings "sailed" on the moat in a small boat-like vehicle, whereby the vehicle capsized and Christoffer drowned. In the family's ancestral Bible there is the entry of the father Adolf Gottlieb Friedrich: “Anno 1775, October 8th at 2 am my son Johann Christoffer was born on Sunday. He drowned on December 8th, 1787. "The church book of St. Nikolai in Greifswald notes" On December 8th, 1787 the light-maker Friedrich's blessed son, 12 years old, drowned because he wanted to save his brother who had fallen into the water. " A mild beginning of December 1787 speaks against the ice-cream variant. The woodcut Boy Sleeping on a Grave from 1801 is regarded as a processing of the death of his brother Christoffer.

Suicide attempt

An important event in the history of a depressive illness is a traditional suicide attempt by Friedrich. The sources for this can also be found after Friedrich's death, come from the anonymous article in the Blätter für literary entertainment from 1843 and from Carl Gustav Carus, who wrote in his memoirs “how he once really tempted himself to attempt suicide could find ”.

"He had already sustained a deep wound on his neck in a lonely hermitage when the door was thrown open and he was not only rescued, but was also able to pledge his word of honor by failing to attempt any new attempt against his life."

When this event can be noted in Friedrich's life is controversial. After a detailed analysis of drawings and biographical information, Helmut Börsch-Supan dates the suicide attempt to the first half of 1801. Carsten Spitzer sees a period between 1803 and 1805. Anecdotally, it is reported that Friedrich grew a whiskers to close the scar on his neck cover up. Following a comparison of the known self-portraits, the suicide attempt would have occurred between 1800 and 1802. Both time variants are mutually exclusive in the argumentation. There is also the possibility that Friedrich, who often spoke in allusions, was misunderstood.

Diagnosis and portraits

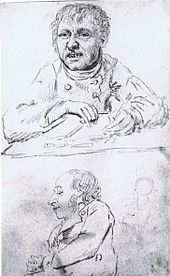

In direct diagnostics, the focus is on the painter's self-portraits. Dieter Kerner analyzes the well-known chalk drawing from 1810 and assumes a quasi-photographic accuracy of the details shown. He notices a difference in the pupil sizes of the eyes ( anisocoria ) due to the lack of a consensual light reaction . Since the left pupil is not only rounded, but also triangular, this suggests an advanced stage of cerebral syphilis ( neurolues ), i.e. an untreated syphilis disease. Herein lies the cause of Friedrich's stroke in 1835. Since Kerner wrongly dates the portrait to 1820 and puts the corresponding symptoms in the course of time, the diagnosis is viewed as questionable. Lange-Eichbaum refers to the portrait of Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein , completed in 1823 , which in no way reveals any symptoms of syphilis. Helmut Börsch-Supan interprets Friedrich's self-portrait in the drawing of a double portrait from September 7, 1800 from the disbanded Mannheim sketchbook as an expression of a difficult psychological situation. The depiction of the head, with its features distorted and aged into a painful grimace, seemed like a cry of desperation at the beginning of a diary in pictures. The open mouth demonstratively shows the damaged teeth. Börsch-Supan interprets the sketchbook as a unique document of Friedrich's mental life and also interprets idyllic motifs as scenes of a dramatic life situation after the assumed suicide attempt. Detlef Stapf, who identified the lower portrait as that of Franz Christian Boll and was able to shed light on the biographical circumstances when the drawing came about, comes to a completely different conclusion. During a hike together in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, Friedrich put himself in relation to the calm pastor as an extremely fearful person.

Disease and symbolism

In Friedrich's pathography, the painter's works tend to be indicative. Primarily the subject of death is used, but there are also interpretations of motifs in comparison to suspected episodes of illness, whereby the selection of works differs in the medical perspective from those in the art-scientific perspective. Dieter Kerner suspects that some works from around 1834/35 such as “Skeletons in the Dripstone Cave”, “Angels in Adoration” or the “Allegory of Heavenly Music”, which one should look at from the sounds of a glass harmonica , are paranoid-hallucinatory images of progressive paralysis as a result of the syphilis . However, this is an isolated position. After Friedrich's stroke, the ever-present motives for death increased as a result of the Depression, which is evidenced by the frequently occurring symbolism of vultures, graves, grave crosses, owls and dead trees.

Work and psychoanalysis

In Friedrich's case, one of the art historical strategies of work interpretation is to compensate for missing image contexts with psychoanalytic explanations. The most striking example of such a procedure is the interdisciplinary discussion on the painting chalk cliffs on Rügen . The picture is most often interpreted as the “wedding picture” that Friedrich and his wife showed during their honeymoon on the island of Rügen in the summer of 1818. Because the second male person in the picture can hardly be assigned to a coherent sense of the image, the two male figures are assigned a double self-portrait of the artist. A psychoanalytic level of interpretation describes the double self-image as an expression of a division of the man into a loving-affectionate and an independent, freedom-loving personality; influenced by traumatization and loss of objects in childhood. The look into the abyss could be a look into the time of painful events and justify the self-created doppelganger. So the painting would be an inner portrait of the artist of himself, a hardly masked form of self-analysis. Detlef Stapf sees a tendency towards dissociation in Friedrich when the painter expresses his texts in the third person in his utterances in areas of conflict, for example in the Ramdohr dispute about the Tetschen Altar , and thus distances himself from the disharmonious part of his personality.

In most interpretations, the painting The Monk by the Sea is the clearest artistic communication about coping with pain, loneliness, powerlessness and the experience of loss. It is used as evidence of the human ability to survive and to resist unbearable pain. The painter succeeds in formulating the message in such a quality that the picture can be an offer to alleviate the pain of the person by becoming visible in the picture.

Oedipal conflict

Detlef Stapf addresses Friedrich's relationship to women, which can be shaped by his sister Catherina, who for him was a substitute mother and ideal mother image. There is much to suggest that the idea of a virtuously pure relationship between Frederick and Julia Kramer and Caroline Bardua should fill the no longer feasible closeness to his deceased sister Catherina. The longing for a tight, oedipal tinted bond with a projection object created a constant fear of rejection, disappointment and hurt. It is at this level that the psychogenesis of Friedrich's depression may be set. How the painter seeks the illicit proximity to the object of desire in the imagination can be seen in several examples in his art. This is coded color-symbolically in the pictures of women in the work. Red for passion can be found in the painting garden terrace (red cloth) or in the painting Woman in front of the setting sun (ruby red earrings), white for virtue with the sisters on the Söller at the harbor (white flowers). The fact that Friedrich, who was always dressed in a dark cloth, wore white trousers and a red jacket in the mountain landscape with rainbow in the self-portrayal that emerged shortly after his sister's death , can be seen as a figurative expression of the Oedipal conflict.

depression

The existence of a depression in Friedrich is widely recognized in art studies and in pathographic analysis, even if the material basis for a diagnosis is recognized as inadequate. From an epidemiological point of view, today's findings are compared with the information from the biography via a prototypical course. According to this, the painter is said to have been ill for the first time at the age of 25, then every 3 to 10 years with depressive episodes lasting between 6 and 12 months. Thus, he suffered two thirds of his life from severe, recurring depression. According to Spitzer, the course of the disease with recurring phases and a suicide attempt is classic for moderate to severe unipolar depression. In the course of the Depression, art historians argue with the repeatedly reduced productivity in the creative process, changes in artistic technique and the accumulation of death symbols in the work phases. As the depression subsided, Friedrich repeatedly achieved a good level of psychosocial functioning. In the predisposition of personality, the artist can be seen as a “prime example” of the melancholic type. For psychodynamics, early childhood losses and early traumatisation are cited. Due to the self-doubts expressed by Friedrich and adequate assessments of trusted contemporaries, one can assume a considerable conflict of self-worth, with a narcissistic difference between one's own ideal and a devalued self-image.

"[...] a very high concept of art, an inherently gloomy nature and a deep dissatisfaction with one's own achievements resulting from both [...]."

Paranoia

In art-historical literature, the derivation of the delusions of jealousy and persecution persisted from the statements of Carl Gustav Carus, as stated in Fritz Nemitz 's biography of Friedrich for the year 1824 without a reason and described by Börsch-Supan as fears bordering on delusions . According to Carsten Spitzer, one cannot speak of a delusion with the present traditions, but according to relevant statements of the painter, one can speak of psychopathological characteristics of mistrust. There are plenty of reasons for the mistrust: Certainly the increasingly negative reviews of his pictures, the intrigues at the Dresden Academy , the murder of his friend Gerhard von Kügelgen (1820), political disappointments, spying, censorship, the compulsion to hide political views . For Detlef Stapf there is already a reason that could lead to paranoia. Throughout his life as a painter, Friedrich perfectly hid the texts of Franz Christian Boll ( On the Decay and Restoration of Religiosity ) and Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld ( Theory of Garden Art ), which are constitutive sources for large parts of his work, from everyone. He also kept silent about the conceptual approaches to his art, such as for the Tetschen Altar , which could have revealed his suggestions. The psychological pressure of this permanent hermetic isolation of his own world must have pathologically changed the painter's personality.

"[...] you still don't realize that the number of your opponents is legion, for whom no means is too bad to harm [...] a person? [...] Poor devil, you are taking me! because be assured where you are going and where you are, and where you sit and where you lie, and what you do and what you do, you will be turned around from afar (even your desk and letters are not locked to these people), and see there is not a word about your tongue so these crooks do not know how to twist, to your disadvantage and their advantage. Your picture here would certainly find recognition under different circumstances, and the fact that it is still included here certainly has a special reason behind which one wants to hide one's own guilt and thus believe to deceive. "

The last years of life

Friedrich suffered a stroke on June 26, 1835 at the age of 61, probably due to a left-sided subcortical ischemic infarction. As a result, persistent depression in the sense of post-stroke depression is very likely. In August and September he stayed in Teplitz for a cure . The artistic production was very limited by a paralysis of the right hand and came to a standstill at times.

"As for Friedrich, he lives reasonably enough, but paralyzed by the stroke and without work"

Kerner refers to a second stroke in 1837 and a mental derangement in the last three years of life. Nevertheless, he created sepias and watercolors, the motifs of which are interpreted in anticipation of death: a megalithic grave, a wreck on the bank, discarded fishing equipment or returning fishing boats. The sheet of grass and palette is supposed to show the farewell to painting . A picture that Caroline Bardua made in August 1839 gives an idea of the painter's condition .

“Caroline broke her old friend and found him sick. She goes to him every morning now to paint him; yesterday she brought a few small sepia pictures with her, which he gave her - they will be a real ornament of our house. "

Spitzer sees the terms "vegetate" or "mental derangement" used in various sources not aptly characterize Friedrich's condition.

criticism

Jens Christian Jensen sees in the pathography practiced in Friedrich's case no clearer, but more difficult access to the painter's art. With the quasi-diagnostic justification of melancholy, the viewer would be given a superficial explanation to look at his pictures from the aspect of character. Friedrich's main themes, certainty of death and the hope of salvation, are generally of a human nature and have little to do with the undoubtedly present depression. Most of the critics tried to translate Friedrich's revolutionary imagery back into the conventional and where this did not succeed, to excuse with the sadness of the master. What Friedrich rashly describes as melancholy can be seen as lived Protestantism . There is also the danger of locating his art outside of the epoch-specific death theme of Romanticism. Not only the contemporary anonymous sources on Friedrich's state of mind and suicide attempt can be called into doubt, but also the traditions of Carl Gustav Carus. The friend, who had benefited significantly artistically from Friedrich, made his judgment on the supposedly “intellectually unclear conditions” of his former teacher at the point at which he distanced himself from him in aesthetic convictions. Carus agreed unreservedly with Goethe's views of nature and art , who considered Friedrich's path to be a wrong path. This fact suggests exaggerations in Carus' assessment. According to Anja Häse, Carus wanted to marginalize the painter by pathologizing in order to legitimize his own bourgeoisie. Like several contemporaries, the Danish art writer Niels Lauritz Høyen got a different view of the painter in 1822/23.

“His character is very amiable. I've been with him a lot. Every time I went into his painter's room, I felt like it, because there is something unspeakably soothing in his face, in his whole being. "

Course of disease

Synoptic representation of the presumed course of the disease of recurrent depressive disorders by Caspar David Friedrich after Carsten Spitzer.

| year | Age | Sources and other material | Symptoms according to ICD-10 and other characteristics | photos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1799 | 25th | "Terrible languor" (letter from Friedrich) "[...] annoyed me so much that I fell ill on the spot [...]" |

Reduced drive / increased fatigue Turning aggression against yourself (psychodynamics) |

|

| 1803-1805 | 30-32 | Suicide attempt (reported by Carus) Recurring thoughts of death or suicide "[...] only the soul languishes [...]." (Letter from Friedrich August von Klinkowström to Philipp Otto Runge ) "[...] through the anger at the patriotic Matters involved [...]. " |

Suicidality Depressed mood |

|

| 1815-1816 | 41-42 | “I was lazy for a while and felt absolutely incapable of doing something. From the inside out nothing wanted the flowing well was dried up I was empty; from outside I did not want to speak to me, I was dull and so I thought it was best to do, to do nothing. "(Letter from Friedrich) |

Depressed mood Decreased drive Loss of interest Loss of self-confidence Psychomotor inhibition |

|

| 1824-1826 | 50-52 | “For some time now I've been feeling unwell [...]; the more I withdraw into myself through bitter experiences [...]. " " [...] while feeling unwell [...] not allowed to undertake major works [...]. "(Letter from Johann Gottlob von Quandt ) |

Depressed mood. Psychomotor inhibition |

|

| 1828-1829 | 54-55 | "[...] dense cloudy cloud of mentally unclear conditions [...]." (Letter from Carus) | Questionable depressed mood | |

| June 26, 1835 | 61 | stroke | subsequently probably depressed |

literature

- Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008.

- Birgit Dahlenburg, Carsten Spitzer: Major depression and stroke in Caspar David Friedrich. In: Julien Bogousslavsky, Norbert Boller (Ed.): Neurological disorders in famous artists . Basel 2005, pp. 112-120.

- Gisela Greve (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in dialogue . Edition discord, Tübingen 2006.

- Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work . DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999.

- Dieter Kerner: The illness of the painter Caspar David Friedrich . In: Medical world. 25, 1974, pp. 2136-2138.

- Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum, Wolfram Kurth: Genius, madness and fame . Volume 3: The painters and sculptors. 7th, completely revised edition. W. Ritter, Munich 1986.

- Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of Caspar David Friedrich's melancholy. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, pp. 73–95.

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

Individual evidence

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 127.

- ^ László F. Földényi: The early death of the romantics. In: Lutz Walther: Melancholie . Reclam, Leipzig 1999.

- ↑ Martina Rathke: Terrible languor: Caspar David Friedrich suffered from depression. In: Doctors newspaper. September 3, 2004.

- ↑ Susanne Hilken, Matthias Bormuth, Michael Schmidt-Degenhard: Psychiatric beginnings of pathography. In: Matthias Bormuth , Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operationalized diagnosis of Caspar David Friedrich's melancholy. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 82.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operationalized diagnosis of Caspar David Friedrich's melancholy. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert: The acquisition of a past and the expectations of a future life. A self-biography by Gotthilf Heinrich Schubert . Volume II, first section, Erlangen 1855, p. 182 f.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 214.

- ^ Carl Gustav Carus: Memoirs and Memories. Re-edited by Elmar Jansen, Weimar 1966, Volume 1, p. 498.

- ^ Dorothee von Hellermann: Gerhard von Kügelgen (1772-1820). The graphic and painterly work . Berlin 2001, H 50

- ↑ Dieter Kerner: The illness of the painter Caspar David Friedrich . Medical World 25, 1974, pp. 2136-2138.

- ^ Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum, Wolfram Kurth: Genius, madness and fame . Volume 3: The painters and sculptors. 7th, completely revised edition. W. Ritter, Munich 1986, p. 65.

- ↑ Birgit Dahlenburg, Carsten Spitzer: Major depression and stroke in Caspar David Friedrich. In: Julien Bogousslavsky, Norbert Boller (Ed.): Neurological disorders in famous artists . Basel 2005, pp. 112-120.

- ^ Gisela Greve (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in dialogue . Edition discord, Tübingen 2006.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, pp. 73–95.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Kurt Wilhelm-Kästner among others: Caspar David Friedrich and his home . Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1940, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Sheets for literary entertainment . 1843, p. 494.

- ^ Athanasius Graf Raczynski: History of modern German art . Volume 2, Berlin 1841, p. 222.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 2008, p. 124.

- ↑ Kurt Wilhelm-Kästner among others: Caspar David Friedrich and his home . Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1940, p. 28.

- ^ Carl Gustav Carus: Memoirs and Memories . Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag, Volume 1, 1966, p. 165.

- ^ Anonymus: Leaves for Literary Entertainment . 1843, p. 494.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 2008, p. 128.

- ^ Anonymus: Leaves for Literary Entertainment . 1843, p. 494.

- ↑ Dieter Kerner: The illness of the painter Caspar David Friedrich . Medical World 25, 1974, p. 2137.

- ^ Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum, Wolfram Kurth: Genius, madness and fame . Volume 3: The painters and sculptors. 7th, completely revised edition. W. Ritter, Munich 1986.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008, p. 128.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 90, network-based P-Book

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 450.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 450.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings. Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 451.

- ↑ Martina Rathke: Terrible languor: Caspar David Friedrich suffered from depression. In: Doctors newspaper. September 3, 2004.

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, p. 177.

- ^ Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich . Interpretations in dialogue. edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 99.

- ^ Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich . Interpretations in dialogue. edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 103.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 427 ff., Network-based P-Book

- ↑ Ekkehard Gattig: The visibility of the unconscious. Psychoanalytic comments on the effect of the work of art. In: Giesela Greve: Caspar David Friedrich. Interpretations in dialogue . edition diskord, Tübingen 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 55 ff., Network-based P-Book

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 90.

- ↑ Martina Rathke: Terrible languor: Caspar David Friedrich suffered from depression. In: Doctors newspaper. September 3, 2004.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 86.

- ↑ Birgit Dahlenburg, Carsten Spitzer: Major depression and stroke in Caspar David Friedrich. In: Julien Bogousslavsky, Norbert Boller (Ed.): Neurological disorders in famous artists . Basel 2005, pp. 112-120.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts. Greifswald 2014, p. 426 f., Network-based P-Book

- ^ Carl Gustav Carus: Memoirs and Memories. Newly edited by Elmar Jansen, Weimar 1966, Volume 1, p. 165.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008, p. 70.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 89.

- ↑ Gertrud Fiege: Caspar David Friedrich in personal testimonies and photo documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1977, p. 117.

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 238, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in letters and confessions. Henschelverlag Art and Society, Berlin 1974, p. 99.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 86.

- ↑ Birgit Dahlenburg, Carsten Spitzer: Major depression and stroke in Caspar David Friedrich. In: Julien Bogousslavsky, Norbert Boller (Ed.): Neurological disorders in famous artists. Basel 2005, pp. 112-120.

- ^ Sigrid Hinz (Ed.): Caspar David Friedrich in Letters and Confessions, Henschelverlag Art and Society. Berlin 1974, p. 214.

- ↑ Johannes Werner: The Bardua sisters. Pictures from the social, artistic and intellectual life of the Biedermeier period . Leipzig 1929, p. 33.

- ^ Jens Christian Jensen: Caspar David Friedrich. Life and work. DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1999, pp. 92-99.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrich. Feeling as law . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Gertrud Fiege: Caspar David Friedrich in personal testimonies and photo documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1977, p. 116.

- ↑ Anja Häse: Carl Gustav Carus: For the construction of bourgeois art of living . Dresden 2001.

- ^ Sheets for literary entertainment. 1843, p. 493.

- ↑ Carsten Spitzer: On the operational diagnosis of the melancholy of Caspar David Friedrich. A workshop report. In: Matthias Bormuth, Klaus Podoll, Carsten Spitzer (eds.): Art and illness. Pathography Studies. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2007, p. 87 f.