Garden terrace (painting)

|

| Garden and terrace |

|---|

| Caspar David Friedrich , 1811 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 53.5 × 70.0 cm |

| Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg , New Pavilion , Inv. GK I 7878, Berlin |

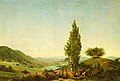

Garden terrace , also palace terrace or view from the terrace of Erdmannsdorf Palace , is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich from 1811 . The painting in oil on canvas in the format 53.5 cm x 70 cm is in the New Pavilion in Berlin .

Image description

In a symmetrical composition, the painting shows a "shaded park area designed according to geometrical rules", delimited by a wall in the middle distance. The center of the picture, formed by a flower ring with a statue of an ancient goddess, is framed by two tall chestnut trees. At the foot of the tree on the right sits a reading woman in a dark dress on a bench, next to her a wicker basket, partly covered with a red cloth. The woman is not depicted as a back figure , but appears as a recognizable person in the side position. In the wall there is an openwork ornamented gate, lined with two lion figures. Behind the wall, the light landscaped area slopes down so that the park area looks like a garden terrace. The background reveals a serene low mountain range with green meadows, wooded hills, village houses and a ruined castle, crowned axially by a mountain cone.

History of interpretation

Contemporary critics emphasized the formal garden design with the designation “Garthenparthie in French style”, whereby the representation of everything French in the time of the Napoleonic Wars was also interpreted as an anti-Napoleonic attitude. In the 19th century, the motif was recognized as the “view from the terrace of Erdmannsdorf Castle” in the Ore Mountains, although there are no indications of Friedrich's stay in this area. In the time of the garden city movement of the 1920s and the discovery of nature as a recreational area, the preferred interpretation of the statue was seen as a symbol of the “calm being” of the landscape and the female figure as a “parable of peace entering man”. Günther Grundmann now locates the garden terrace in the Giant Mountains.

In 1969 Helmut Börsch-Supan introduced the religious and patriotic interpretation into the discussion, recognizing a symbolism (cross in the gate), which refers to a religious meaning in the landscape. Werner Hofmann pleaded in 2000 for an "allegory in which the young woman's imaginary reading experiences solidify into a visible educational altar". With the “garden terrace” Friedrich distances himself from his other, gloomy self.

"To whom nature does not reveal itself in the most delicate harmony, but only in the most abrupt contrast recognizes its spirit, whose meaning is closed to art."

In 2007, Peter Märker insisted on the politically interpretable contrast “French garden - free nature”, which should stand for the feudal hierarchy and the free form of government. In the latest interpretation, Detlef Stapf recognizes the female painter Caroline Bardua , with whom Friedrich was friends well into old age, in a compilation of the Ballenstedt Castle Park and the Harz landscape that can be verified. The elegant city dweller is placed in a strictly shaped, shaded park landscape, which is isolated from the real nature by a park wall and closed gate.

Stay in Ballenstedt

The events before the creation of the garden terrace can be reconstructed. The 27-year-old Caroline Bardua finished art lessons with Gerhard von Kügelgen in Dresden in spring 1811 and returned to her family in Ballenstedt . The Bardua had its greatest success with a portrait at the Dresden art exhibition of 1810, which shows Caspar David Friedrich in mourning. On June 16, 1811, Friedrich set off from Dresden together with the sculptor Christian Gottlieb Kühn on a trip to the Harz Mountains. He and Kühn began a hike in the Harz Mountains on June 23, with a stay of several days at the Bardua house in Ballenstedt. Caroline Bardua was the daughter of a valet of the Prince of Anhalt-Bernburg . The house of the Barduas was at the castle near the chestnut avenue that leads to the city.

“On a Sunday afternoon, when Caroline was sitting at the piano to shorten the somewhat long hours that a holiday afternoon always brings, by singing, two strangers appeared on the street. [...] They immediately came to see Carolinen and being with both artists was a great pleasure for them. "

Friedrich filled his sketchbook with drawings of the area around Ballenstedt Castle and views of the Brocken. Some sheets are provided with typical notes for further use in a painting. After hiking back to Dresden in the Harz Mountains, the painter began working on the garden terrace in the studio in September 1811 .

compilation

Friedrich composed the painting “Garden Terrace” as a compilation. As in a stage space, he brings the scenery into a visual axis and arranges what can be found in the nature at the location (Ballenstedt) distributed in different directions. The park wall is the north-western part of the wall of the old baroque Ballenstedt palace park as it was in 1810 ( Peter Joseph Lenné redesigned the complex into a landscape park from 1858). For the Harz foreland and the Brocken moved into the picture, the painter simulates a plastic closeness that cannot be experienced in such a way. The two chestnut trees belong to the avenue that leads from the castle in an easterly direction towards the city and was laid out in 1800. The woman on the bench under the avenue trees represents the anchor point around which the parts of the landscape are moved. The garden terrace is the only picture in Friedrich's work in which this topographical compilation is also verifiable and allows conclusions to be drawn as to how the painter arranges the fragments of natural reality in other pictures.

“Art acts as a mediator between nature and people. The archetype is too great for the crowd to grasp. "

Sketches

Pencil sketches dated June 25, 1811 with the title Two Landscape Studies were used for the Harz foreland and the outline of the chunk . With a double line and numbering in the depth space , image details are favored for further use. For the two chestnut trees in the painting, Friedrich made plants and foliage studies in Dresden in September 1811, as well as the sketch of a park landscape with two flanking trees .

Provenance

The picture was shown in March 1812 at the Dresden academy exhibition and in autumn 1812 at the Berlin academy exhibition, where it was acquired by the Prussian royal family. The plant was located in the Prinzessinnenpalais in Berlin on the boulevard Unter den Linden until 1843 , in the Villa Liegnitz in Erdmannsdorf until 1906, in the Berlin Palace until 1945 and then in Potsdam , then in the Charlottenhof Palace and today in the New Pavilion in Berlin.

Classification in the overall work

The garden terrace is Caspar David Friedrich's first painting in which the painter places an apparently personalized image in a symbolic relationship with nature. The strictly symmetrical three-clocked picture structure used for this becomes a work-determining, varied design and structural principle of the painter.

Garden images of transcendence

In the series of Friedrich's garden pictures, the garden terrace also creates a new painterly and compositional quality compared to the summer picture from 1807, which is reflected in the lost counterpart Landscape with a Garden (1811), in the memorial picture for Johann Emanuel Bremer (1817) and the gazebo (1818) continues. What these garden pictures have in common is the mediating transcendence of an experienceable present and an unreal distance, separated by a “space barrier” as an element of the garden design. The living or no longer living persons are located in small paradises with the prospect of a world of the non-real. The garden appears as a place of mysterious desires, a symbolic place of romance.

Images of women and the color red

The garden terrace is the first in a series of paintings that show female figures in the landscape and were created before Friedrich's wedding in 1818, which includes the woman in front of the setting sun , the farewell and woman at the sea . In contrast to the housewarming portraits of his wife Caroline, like the woman at the window, these motifs of the still unbound life reveal some passion. The red cloth of the garden terrace , the red dress of the woman by the sea and the ruby red earrings of the woman in front of the setting sun offer a coherent color symbolism, red as the color of love. At the garden terrace you can go out by the red cloth as a sign of admiration for Caroline Bardua. Even in the painting Easter Morning from 1835, which is believed to show the three women who played a role in the painter's life, two of the women are wearing a red cape. Friedrich had the unjustified reputation of being the "most unpaired of all unpaired couples", but in 1803 he noted in his diary:

“Then I was reminded of the beautiful girls I saw a few months ago while I was passing through, and quickly, before it got dark, I hurried to the place. I walked slowly through the quiet streets of the town, and I also saw some of the beautiful girls; they were the same as I've seen. I could even see them clearly through the clear window panes. And hardly give them a friendly greeting when they suddenly twisted backwards and disappeared red with shame. "

Caspar David Friedrich: Woman before the Setting Sun , 1818

Caspar David Friedrich: Woman at the Window , 1822

The new garden image

In the garden subjects of art, the “garden terrace” marks the turning away from the strolling images of English landscape parks towards the representation of the Biedermeier ideal with the garden as a retreat, a place for reflection and artistic inspiration. Until the 1790s, paintings by Francoise Lefebvre, Martin Knoller , Johann Christian Ziegler , Johann Christoph Erhard or Albert Christoph Dies dominated the panoramas of princely parks populated by extras. In the garden terrace, by assembling the princely garden and the avenue in which the people cavort, Friedrich anticipates the idea of the Vormärz of the Volksgarten and places an emancipated bourgeois woman there. With the painting Gartenlaube from 1818 he created "probably the first 'Gartenlaube' in German painting". It was not until around 1830 that painters such as Joseph Eduard Teltscher , Johann Peter Krafft , Thomas Ender , Franz Alt, Carl Daniel Freydanck , Joseph Hasslwander and Moritz von Schwind discovered the garden as a private bourgeois space. This development is continued in the garden depictions of Impressionism, New Objectivity, Art Nouveau and Expressionism in the work of painters such as Claude Monet , Theodor von Hörmann , Gustav Klimt , Emil Nolde , Heinrich Vogeler and Max Beckmann . The depiction of the garden with a woman on the periphery of an axial pictorial center has always been an artist's motif since Friedrich's garden terrace .

literature

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Ed.): Gartenlust. The garden in art , Belverdere Verlag, Vienna 2007

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné)

- Kurt Karl Eberlein: CD Friedrich. Confessions . Leipzig 1924

- Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011

- Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0

- Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007

- Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrich's hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, network-based P-Book

- Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich in the Harz Mountains . Verlag der Kunst, Amsterdam and Dresden 2000. New edition 2008, ISBN 978-3-86530-104-8

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 321

- ↑ Journal des Luxus und der Fashions , year 1812, p. 357

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 321

- ^ Günther Grundmann: Silesia and Caspar David Friedrich. In: Schlesische Monatshefte VII, 1930, pp. 413–428

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Caspar David Friedrichs memorial picture for the Berlin doctor Johann Emanuel Bremer . In: Pantheon XXVII, 1969, pp. 399-409

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 108

- ^ Kurt Karl Eberlein: CD Friedrich. Confessions . Leipzig 1924, p. 102

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 107 ff

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, pp. 46–52, network-based P-Book

- ^ Anonymous: Art exhibition in Dresden , Journal des Luxus und der Moden, 1810, pp. 313, 349, 352

- ^ Herrmann Zschoche: Caspar David Friedrich in the Harz Mountains . Verlag der Kunst, Amsterdam and Dresden 2000. New edition 2008, ISBN 978-3-86530-104-8 , p. 23

- ^ Walter Schwarz: Youth life of the painter Caroline Bardua. Based on a manuscript by her sister Wilhelmine Bardua . Hoffmann, Breslau 1874, p. 58

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 51, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 50, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Hans Schöner: The Selke rustled lovely. Ballenstedt at the time of the Kügelgen with 60 watercolors by Anna and Bertha von Kügelgen and texts by Wilhelm von Kügelgen and Wilhelmine Bardua , self-published, Kiel 1993, p. 47

- ^ Kurt Karl Eberlein: CD Friedrich. Confessions . Leipzig 1924, p. 118

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 51, network-based P-Book

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 622

- ↑ Christina Grummt: Caspar David Friedrich. The painting. The entire work . 2 vol., Munich 2011, p. 538

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 321

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 102

- ^ Peter Märker: Caspar David Friedrich. History as nature . Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, p. 69

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Paintings, prints and pictorial drawings , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9 (catalog raisonné), p. 347

- ↑ Detlef Stapf: Caspar David Friedrichs hidden landscapes. The Neubrandenburg contexts . Greifswald 2014, p. 79 f., Network-based P-Book

- ^ A. and E. von Kügelgen: Helene Marie von Kügelgen, b. Zoege from Manteufel. A picture of life in letters . Belsersche Verlags-Buchhandlung, Stuttgart 1922, p. 144

- ^ Kurt Karl Eberlein: CD Friedrich. Confessions . Leipzig 1924, p. 72

- ↑ Agnes Husslein-Arco (Ed.): Gartenlust. The garden in art , Belverdere Verlag, Vienna 2007, p. 118 f.

- ^ Werner Hofmann: Caspar David Friedrich. Natural reality and art truth. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46475-0 , p. 112

- ↑ Agnes Husslein-Arco (Ed.): Gartenlust. The garden in art , Belverdere Verlag, Vienna 2007, p. 111 f.