Heinrich Vogeler

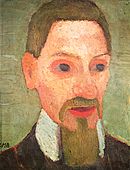

Johann Heinrich Vogeler (born December 12, 1872 in Bremen , † June 14, 1942 in Kolchos Budjonny near Kornejewka, Karaganda , Kazakh SSR ) was a German painter, graphic artist, architect, designer, educator, writer and socialist. The versatile artist is best known for his works from the Art Nouveau period. He belongs to the first generation of the Worpswede artists' colony , his home, the Barkenhoff , became the focus of the artistic movement in the early 1900s. During the First World War he developed an expressionist style of painting, and from the early 1920s, after visiting Moscow , he created complex paintings with political motifs based on Cubism and Futurism . After moving to Moscow in 1931, he began to paint in the style of the socialist realism demanded by the Soviet Union .

Vogeler, who came from the bourgeoisie, approached the labor movement, in 1919 transformed the Barkenhoff into a socialist commune with an attached work school and studied the writings of Marx , Engels and Bakunin . After moving to Moscow, he became involved in the cultural and political spheres, for example in the anti-fascist movement against Hitler . After the German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, like many other Germans, he was evacuated under duress and came to the Karaganda region of Kazakhstan. He died under tragic circumstances in exile in the Soviet Union.

Live and act

Youth and career

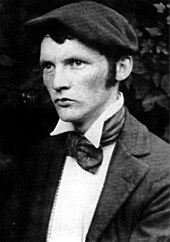

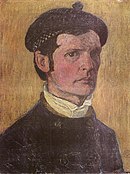

Vogeler grew up as the second of seven children of the hardware wholesaler Carl Eduard Vogeler and his wife Marie Louise, nee. Förster, in middle-class circumstances in Bremen. The first and third children died early, so that Heinrich, as the oldest, was to take over the father's business. He graduated from the unpopular school with a secondary school leaving certificate and was supposed to begin an apprenticeship in a Bremen trading company. However, Vogeler was able to convince his father to allow him to study at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf , which corresponded to his artistic inclinations. Vogeler began studying art in Düsseldorf in 1890 and became an apprentice at the art academy in February 1892. In September 1892 he interrupted his studies, among other things due to a conflict with his teacher Johann Peter Theodor Janssen . He did not agree with the teaching methods, stayed away from the art history lectures and obtained a reprimand from the academy professor. In the spring of 1893 he returned to the academy and finished his studies in the winter semester of 1894/1895. During his studies he became a member of the student painter association Tartarus and was called Mining there, after a fictional character by Fritz Reuter . This moniker would stay with him for a lifetime. Vogeler's father died in autumn 1894, the family business was sold, and his inheritance allowed Heinrich Vogeler to lead a carefree artistic life for the time being. After studying (1890–1894 / 95), interrupted by trips to Holland, Bruges, Genoa, Rapallo and Paris, he joined the painters Fritz Mackensen , Hans am Ende , Otto Modersohn , Fritz Overbeck and Carl Vinnen in the Worpswede artists' colony in 1894 on. Hans at the end introduced him to the technique of etching . Joint exhibitions in the Glaspalast in Munich in 1895 and 1896 made the group of painters from Worpswede known throughout the country and brought many awards.

The early work

Vogeler's early painting took a special position, it is Pre-Raphaelite and is in the tradition of the English group of painters around Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones . Contrary to academic doctrine, this group sought its inspiration in Italian painting of the 15th century and later influenced the development of Art Nouveau with its biblical, mythological or fairytale themes.

Like the Pre-Raphaelites, Vogeler transferred biblical themes and motifs from legends to his home landscape. One example is the painting Winter's Tale from 1897, in which the Three Wise Men appear in princely clothing and wooden shoes in a winter landscape in Worpswede. Further examples of his early Pre-Raphaelite works are Spring , Homecoming , Farewell (1898), Swan Tales (1899), Lovers (1901) and Annunciation from 1902. The Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli was a role model for him, and he recognized his pictures his own longing for a better time. A reproduction of Botticelli's The Birth of Venus hung in his studio . Vogeler was not satisfied with his painting, as he sensed the qualitative difference to his models from the Renaissance period .

Another focus was Vogeler's graphic work, which established his reputation as an Art Nouveau artist. The romantic etchings between 1895 and 1899, such as Storch überm Weiher from 1899 and the illustrations for Gerhart Hauptmann's The Sunken Bell , met with great approval both at home and abroad. Printmaking, "social painting" as he called it, became very popular with the educated middle class due to its wide distribution.

Vogeler was very successful with his graphic works: at Eugen Diederichs Verlag, founded in 1896, he took on illustration tasks and worked for the literary magazine Die Insel - from 1901 the Insel Verlag . The island was founded in Munich in 1899 by Otto Julius Bierbaum , Alfred Walter Heymel and Rudolf Alexander Schröder as a literary monthly magazine with book decorations and illustrations . It showed the aesthetic ideas of the bourgeois reform movement in Wilhelmine Germany and was intended to renew German book art , which had fallen to a low level in the 19th century. Vogeler was won over for the artistic design of the magazine and the books of the publisher; he designed illustrations , vignettes , moldings and book covers in order to combine them with the literary content to form an aesthetic unit. The publisher's first publications included his illustrated volume of poetry, Dir and the portfolio of etchings An den Frühling, as well as the illustrations for Oscar Wilde's fairy tales. The closeness to Aubrey Beardsley's English drawing and book art and to the Arts and Crafts movement is evident.

Vogeler later described his early drawings for Insel Verlag as an escape from reality:

“My graphic works from this time probably expressed the lack of horizon. Unconsciously, a purely formal, unreal fantasy art without content arose. It was a romantic escape from reality, and therefore it was also a desirable distraction for the bourgeoisie from the threatening social questions of the present. [...] So my island graphic met the character of a special time epoch, which somehow also shaped my character, a boundless romanticism, behind all reality and in contradiction to it. "

Vogeler held his first major special exhibition in the fall of 1898 in Arno Wolfram's art salon in the Viktoriahaus in Dresden . On behalf of the Cologne chocolate producer Ludwig Stollwerck , he created the Stollwerck picture series "Goose Maid - King's Son" published in 1902, which was accompanied by verses by Franz Eichert.

Vogeler made his longest trip to Italy from November 1902 to March 1903. In Rome, stay in the studio of his friend Otto Sohn-Rethel in the Villa Strohl-Fern , on to Naples with a visit to Pompeii and inspection of the frescoes by Hans von Marées in the Zoological Station , back to Rome and from there to Florence in the north of Italy , Bologna, Padua, Vicenza and Venice. At that time, his painting, First Summer, was exhibited at an exhibition at the Berlin Secession on Kantstrasse .

In 1904 Heinrich Vogeler was one of the artists who took part in the first exhibition (made possible by the Munich secessionists ) for the members of the German Association of Artists in the Royal Art Exhibition Building on Königsplatz ; there he showed the oil painting Annunciation for the first time .

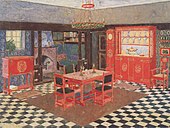

Life on the Barkenhoff

Vogeler's house, which he called Barkenhoff ( Low German for Birkenhof ), originally a farmer's cottage, he designed from 1895 according to the principles of Art Nouveau and transformed it into an artist's residence with furniture, crockery and wallpaper he designed himself. He decorated the garden with symmetrically arranged flower beds and hedges and planted a birch grove, which gave the house its name. The property as a total work of art of architecture, art, interior design and garden should be connected with Vogeler's life. In his clothes he adapted to this dream world and wore a stand-up collar, top hat and lap skirt as in the Biedermeier era . He designed clothes and jewelry for his wife Martha and wanted to take her with him into his dream world. Probably the model was William Morris , who had his Red House with interior fittings and garden built in Bexleyheath, Kent , according to his own designs in 1860 .

The Barkenhoff became an important meeting point for the artists' colony . The Barkenhoff family included the poet Rainer Maria Rilke , his wife, the sculptor Clara Rilke-Westhoff , Otto Modersohn, Paula Modersohn-Becker , Paula's sister Milly, his wife Martha Vogeler , his brother Franz with his wife Philine. The three couples Rilke, Modersohn and Vogeler married in 1901.

Rilke's saying "Light is his lot / the Lord is only the heart and hand / of the building with the linden trees / his house will also be / shady and large", which the poet had written for Christmas in 1898, Vogeler left as Notch house blessing in the entrance door of the Barkenhoff. The visitors of the house included Richard Dehmel , Gerhart Hauptmann , Carl Hauptmann , Thomas Mann , the Insel- Verlag founder Rudolf Alexander Schröder and Max Reinhardt . On Sundays, the circle of artists read and recited, danced, sang and created life as a work of art. But the common festivals masked the fact that the similarities were less and criticism of the art of the others arose. The artists no longer exhibited as a group since 1902, and the marriages that had just been concluded showed the first cracks; the new century demanded new approaches. In Vogeler's dream world there was no place for real life. Martha, whom he pressed into a fantasized image of a woman and whom he could only love from a protective distance, slipped away from him more and more. This is evident in many of the portraits she has painted, which have a cool distance. He recognized the dead end into which he had come when asked about the meaning of his life:

“I arranged everything so that the guests felt themselves to be the bearers of the party. But before a festival reached its climax, I was gone, angry with myself for no reason. Why couldn't I have a festival? I never understood why I, the lucky guy, this person, who succeeded in everything he touched, now sat there, far from the festival on the lonely mountain slope, a little heap of misery, my head in my hands and staring at the bare meadow river [... ]. "

In 1905 Vogeler completed his well-known large-format painting Summer Evening (also called The Concert ), which shows a concert on the terrace of the Barkenhoff and depicts his wife Martha as the central figure, who looks thoughtfully into the distance. The Russian borzoi in front of her on the stairs was a present from Alfred Heymel . With the exception of Rilke, almost all of the people in the Barkenhoff family are gathered there. Vogeler, half hidden on the far right, depicts himself playing the cello, his brother Franz is sitting with his violin on his left, the flutist is his brother-in-law Martin. On the left of the picture you can see Paula Modersohn-Becker, next to her Agnes Wulff and Clara Rilke-Westhoff. The bearded man in the background is Otto Modersohn. The painting was shown in Oldenburg on the occasion of the Northwest German Art Exhibition. There Vogeler was awarded the Great Medal for Art and Science . The summer evening is considered the culmination of his first creative period.

The gold chamber in the Bremen town hall

Between 1904 and 1905, Vogeler redesigned the gold chamber in Bremen's town hall for the Bremen Senate, following the recommendation of the Kunsthalle manager Gustav Pauli . He designed the small room, which was built into the Upper Hall as early as 1595, entirely in Art Nouveau style, from the door handles to the fireplace grille and the candlesticks to the gilded leather wallpaper. This work made him known in the arts and crafts sector. He also designed cutlery, glasses and furniture that were sold in the Kunst- und Kunstgewerbehaus Worpswede GmbH , founded by his younger brother Franz, and that brought him more success than his painting.

social commitment

Because of an eye problem, Vogeler took a sea voyage to Ceylon to relax in 1906 ; the British colonial rule there shocked him. During a trip to Lodz in 1907 he got to know the social commitment of a factory owner's wife who campaigned for working-class families. These experiences, especially reading the works of the Russian writer Maxim Gorki , aroused Vogeler's willingness to stand up for the interests of the working class.

In 1907 he hired the painter and architect Walter Schulze as an employee, enlarged the Barkenhoff and began planning the Worpswede train station. In the same year Vogeler was a co-founder of the Deutscher Werkbund . A year later he and his brother Franz founded the Worpsweder Werkstätte in Tarmstedt , a carpenter's workshop for the production of inexpensive series furniture that should be affordable for the less well-off. As a city planner, he campaigned for affordable housing. In 1909, for example, he traveled to England with a study group from the German Garden City Society , where he visited an exemplary workers' settlement in Liverpool, Port Sunlight , but also got to know slums in Glasgow and Manchester . However, the implementation of the design of a workers' village for the employees of a furniture factory in the Bremen area failed for financial reasons. He couldn't find any sponsors and was advised to paint beautiful pictures again.

In 1910, his interior design work was recognized at the Brussels World's Fair , but his Art Nouveau graphics no longer found supporters. His marriage got into a crisis because Vogeler's wife had started a relationship with the student Ludwig Bäumer . In 1912 he designed the house in Stryck in Willingen in the Sauerland for his friend Emil Löhnberg , which he equipped with natural building materials and where he was often to stay as a guest. In autumn he left the Barkenhoff and set up a small studio in Berlin, in which he designed bookplates and advertising graphics, for example for the Bahlsen company .

First World War, social utopias

Vogeler volunteered at the front during World War I in 1914 and was deployed as an intelligence officer in the Carpathian Mountains , where he made drawings of the war zone on behalf of the General Staff: the portfolio Aus dem Osten , which appeared in 1916. Through the experiences he made there, he became a radical pacifist and an opponent of the German Empire in 1917 . From then on he was committed to the revolutionary working class. Heinrich Vogeler also drastically changed his previously ornamental style. He developed an expressionist style of painting, which is shown for example in the oil paintings The Sick and The Suffering of Women in War .

In the last months of the war, politically interested prisoners of war who had to do forced labor for large farmers, German revolutionaries and left-wing intellectuals met at the Barkenhoff. They discussed the social changes in Russia and the possibilities of a revolution in Germany. Vogeler represented a socialism based on primitive Christian values and, according to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon , idealized self-governing communities whose members live peacefully and without property. In January 1918 he wrote his appeal for peace, The Fairy Tale of the Dear God, to the German Emperor Wilhelm II :

- “Be a Prince of Peace, put humility in the place of vanity, truth instead of lies, construction instead of destruction. On your knees before the love of God, Kaiser! "(Excerpt from Vogeler's letter of peace to the Kaiser)

Vogeler was then arrested while on leave from the front for defeatist activities and was admitted to an observation station for the mentally ill in a Bremen hospital for 63 days. He returned to the Barkenhoff in April 1918. During the November Revolution of 1918/1919 he was a member of the Workers 'and Soldiers' Council in Osterholz . On February 4, 1919, the Bremen Soviet Republic was smashed. The dream of a new society claimed 75 lives and the representatives of the councils were persecuted; Vogeler had to flee. He was arrested in Willingen, but was able to return to Worpswede in March. In May he was arrested again because the Barkenhoff was considered a left-wing extremist center that could pose a threat to the new order. Among other things, the former sailor and later ceramicist Jan Bontjes van Beek had sought refuge on the Barkenhoff, which he left again in the summer. After his release, Vogeler resisted the agitation in the Bremer Nachrichten of June 3, 1919 and suspected - albeit without naming his name - a spying by his former artist friend Fritz Mackensen, who had become a member of the paramilitary Bund Stahlhelm .

Barkenhoff municipality and work school

Together with Marie Griesbach , the Red Marie , with whom he had a temporary relationship, and other friends, Heinrich Vogeler founded the Barkenhoff commune and work school in the summer of 1919 to prove that a new society is possible. The desired self-sufficiency was to be achieved through intensive horticulture, and so the Art Nouveau garden was rededicated as a vegetable garden. The household waste was composted and well and sprinkler systems were installed. With the neighboring settlement of the Hamburg landscape architect Leberecht Migge , the Sonnenhof , an exchange of workers and agricultural machines was planned according to the principle of mutual help . Under the direction of Friedrich Harjes there was a metal workshop that was supposed to help finance the community. There craft metal objects were created based on Vogeler's designs as well as tools and everyday objects. Harjes drove the symbol of the commune, a large hand that protects a child, into sheet brass. A wood workshop under the direction of the carpenter August Freiträger completed the range of services offered by the municipality. Vogeler could not accept a proposal to join the KPD , which was founded in 1919 , for ideological reasons there was no place for the utopian socialist. As early as September 5, 1918, he wrote to his friend, the Bremen coffee manufacturer and patron of the arts , Ludwig Roselius : “You will never find me on any barricade, because I stand up for the peace of mankind.” In the first post-war years, Vogeler also sympathized with the ideas of the Anarchism or anarcho-syndicalism and wrote for the "free worker", organ of the " Federation of Communist Anarchists of Germany " and for the " syndicalist ", organ of the Free Workers' Union of Germany .

In 1920 Martha Vogeler moved with her three daughters Marieluise (called Mieke, later second wife of the writer Gustav Regulator ), Bettina and Martha and her friend Ludwig Bäumer into the house in Schluh , an old moor cottage from the village of Lüningsee, which she and Vogelers financially Relocated support to Worpswede and had it rebuilt there. He gave her a lot of furniture from the Barkenhoff and ceded all rights to his pre-war works to her; the fairytale court was a thing of the past. The Barkenhoff community became his new family. For the children on the farm, who were supposed to grow up in an anti-authoritarian way, he developed educational plans for upbringing and designed the work school , which, in contrast to the bourgeois school, “encourages the organically growing and liberating creative process in the child to come to life in order to enable the young person to develop full individual creative power to bring work for the benefit of his fellow men. "

First trip to the Soviet Union, complex pictures

Between 1920 and 1926 Vogeler painted the hall of the Barkenhoff with murals, thematically linked to the labor movement, at times together with his daughter Mieke. In 1923 he went on his first trip to the Soviet Union, together with Zofia (Sonja) Marchlewska (1898-1983), the daughter of the Polish communist Julian Marchlewski (friend and colleague of Rosa Luxemburg , confidante of Lenin and founder of the International Red Aid ) had already met in Worpswede in 1918. He had the hope of being able to participate creatively in the construction of a more humane society in the Soviet Union: “An artist, an apolitical, communist philosopher comes to Russia as a seeker. [...] As a designer he is in the midst of the crystallization process, he sees the clear, future-oriented structure of the Union of Soviet Republics, he recognizes the living organism of the society of workers. "

Vogeler remained in Moscow as a low-paid university employee until September 1924 , where he developed his new style of complex paintings , the first version of which can be seen in the 1918 etching The Seven Bowls of Anger . The crystal-like structure of these pictures often shows a cross-picture symbol such as hammer and sickle or a star, such as the 1923 oil painting The Red Metropolis . With this technique he created the painting The Birth of the New Man , to which the birth of his son Jan on October 9, 1923 in Moscow inspired him. According to Hans Liebau, who wrote a dissertation on Vogeler's frescos and complex paintings published as a book in 1962, Vogeler tried , in accordance with the materialistic dialectic , to point out characteristic interrelationships, internal connections and conditions in his complex paintings by reproducing various important aspects of a social problem. Liebau also sees striking similarities between Vogeler's complex paintings and Diego Rivera's murals in terms of content and form. The Mexican artist knew Vogeler's murals from his visit in 1927, when he stopped in Worpswede on the way to Moscow.

In the autumn of 1924 he left Moscow for Berlin after he had turned down an offer from his friend Ludwig Roselius to set up a studio for him in Bremen.

Barkenhoff children's home

The labor school got into a financial crisis because it was denied public funding. From 1923, on the suggestion of Julian Marchlewski, the Barkenhoff was used as a children's home for the newly founded Rote Hilfe Deutschland (RHD) - Vogeler was a founding member and served on the central board - and received financial support. On December 23, 1924, he signed a purchase agreement in Berlin under which the Barkenhoff became the property of Rote Hilfe (Quieta Erholungsstätten Limited Liability Company). The purchase price was 15,000 gold marks (around 50,000 euros).

According to the ideas of the RHD, "needy working-class children whose fathers or mothers were in prison for political reasons or who had died in the political struggles of the early 1920s should recover [...] and experience a socialist upbringing". In September 1923, the first group of 18 children came to Barkenhoff for six weeks, supervised by the pedagogue Ernst Behm . In addition to a political upbringing in the spirit of the KPD, these children also had a variety of opportunities for practical work in the existing workshops, the garden and in the kitchen, and based on the Russian model of the production school , Behm was also able to practice approaches of a work school .

Georg Jungclas also worked there during this development phase of the school . He and Behm left the Barkenhoff, Jungclas, in 1923 to take part in the Hamburg uprising , and Behm to help set up a progressive school system in Thuringia . There, however, he was soon removed from school service for political reasons, and he returned to the Barkenhoff in 1924. In the meantime, the pedagogue Karl Ellrich worked there , and together with him, Behm was able to further develop the concept of working lessons and develop child-friendly forms of political theater and political discussion. But the conservative press quickly mobilized against him as a person as well as against the alleged political influence on the children on the Barkenhoff, and the district administrator presented the RHD with the alternative of either dismissing Behm or closing the facility. In order to save the home, Behm left the Barkenhoff in February 1925 after consulting with leading KPD comrades.

In 1926, the Barkenhofflied was published in the magazine for workers' children, the drum , with the text and music of Helmut Schinkel . It is a bedtime song in which the children wish their distant mothers and imprisoned fathers good night and hope for freedom that will grow overnight. From August 1924 to December 1925, Schinkel was a teacher and educator at the Barkenhoff. The later director of the Karl Liebknecht School in Moscow “was arrested by the NKVD on July 5, 1937 on charges of being a“ member of a counter-revolutionary fascist group ”. On January 10, 1938, he was sentenced to eight years in a camp. Helmut Schinkel died on May 31, 1946 in an NKVD camp in the northeast of the European part of the Soviet Union ”.

The children's home had to be closed in 1932. According to Vogeler, he joined the KPD in late summer 1925.

Between the Soviet Union and Fontana Martina

From the end of June to September 1925 he traveled again to the Soviet Union, to Karelia , on behalf of the Red Aid, in order to document the construction there for propaganda purposes. Another trip to Moscow followed in November to prepare the Red Aid Congress.

After Martha Vogeler separated from him, he married his partner Sonja Marchlewska after the divorce in 1926. He was able to achieve a compromise against a campaign to remove his murals in the Barkenhoff and to close the children's home: The murals were not destroyed, but fitted with lockable roller curtains. The unsuccessful iconoclasm made his murals known internationally. The Mexican painter Diego Rivera , later husband of Frida Kahlo , known for his murales , wall paintings with socio-political themes, visited the Barkenhoff in autumn 1927. Letters of protest against the destruction demanded by the district administrator of Stade came from, among others, Eduard Fuchs , Lion Feuchtwanger , Hermann Hesse , Käthe Kollwitz , Thomas Mann , Max Pechstein and Kurt Tucholsky . In 1938 the frescoes fell victim to a renovation.

Numerous trips for the Red Aid left little time for his painting and for his family. His political activity was poorly paid. In order to promote the sale of his pictures, he therefore joined forces with other Worpswede artists such as the sculptor Bernhard Hoetger , Otto Modersohn, the weavers Martha and daughter Mieke Vogeler and his sister-in-law Philine as a gallery owner for the Economic Association of Worpswede Artists .

In May 1927 the family moved into an apartment in the Hufeisensiedlung in Berlin-Britz, which was newly built by Bruno Taut . From October 1927 to 1929, the year of the Great Depression , Vogeler worked in the Berlin advertising and architectural firm The ball of the later resistance fighter Herbert Richter , where he advertising posters, for example, for Kaiser's coffee. designed to make a living for the family. His pictures with a political theme, such as the complex picture of Hamburg shipyard workers from 1928, did not go down well with the wealthy upper middle class.

His marriage was in crisis; Sonja had a love affair with the self-taught artist Carl Meffert , while Vogeler had a relationship with his office colleague Ursula Dehmel. In the winter of 1928, he and his son Jan visited the Ticino mountain village of Ronco near Ascona , where his friend, the communist Swiss book printer Fritz Jordi, was planning a settlement based on the Barkenhoff model in the hamlet of Fontana Martina. To the failure of his marriage came the loss of his political home. Vogeler was expelled from the KPD in January 1929 because he was a supporter of the Communist Party opposition , and in October 1929 he was also voted out of the central executive committee of the Red Aid. Between October 1931 and November 1932 Ronco published the semi-monthly magazine Fontana Martina, which was published together with Jordi .

Emigration to the Soviet Union

Vogeler's last trip to the Soviet Union in 1931 was final; There he accepted the assignment to work on a committee for the standardization of the building industry. In 1932 he was head of the propaganda department in Tashkent , which was supposed to take care of increasing yields by stimulating seeds. During his travels through Uzbekistan , he made many sketches about the rural population. Among other things, he processed his travel experience in the complex image of cotton .

Through the takeover of the National Socialists him the way back in 1933 was cut to Germany. Many persecuted intellectuals and artists emigrated to Moscow, among them Erwin Piscator , Wilhelm Pieck and Clara Zetkin , who died in June 1933. Vogeler drew them empathetically on the deathbed. In 1934 he created his complex picture The Third Reich , in which he depicted Hitler roaring and with swastikas instead of eyes. In 1935 he was the artistic director of an exhibition of the International Red Aid (MOPR), in which he was also represented with pictures against the Third Reich: among other things, book burning in Berlin , torture chamber of the SA and concentration camp .

The Stalinist era claimed its victims among Vogeler's neighbors, who were picked up by the state police and disappeared. As the son-in-law of the revolutionary Marchlewski, he was not affected by persecution. So he took an attitude loyal to the party, but guarded against denouncing. Vogeler applied several times to be re-admitted to the KPD. When that didn't work, he tried to become a member of the Soviet Communist Party - but to no avail. His hopes of finding the better world he had longed for in the Soviet Union were, however, tarnished. In order to avoid the accusation that his art was still too bourgeois, he gave up the complex painting style he had developed in 1934. Because he had to adapt to the form of expression of socialist realism prescribed by the state . He destroyed some of the complex pictures that he created during this time or converted them into realistic pictures.

At the end of the thirties he was given a new creative task: he designed a puppet stage in Odessa with heads and clothing for the hand puppets for the German Collective Theater, and he worked enthusiastically on their imaginative execution. This was followed by an order for sets for the puppet theater.

In March 1941, the marriage with Sonja was divorced. Vogeler intensified his anti-fascist work by writing leaflets and radio addresses against Nazi Germany. On May 26, Wilhelm Pieck opened an exhibition of his works loyal to the regime from 1936 onwards in Moscow. It was the year of his 50th anniversary in employment, but Vogeler's wish to have his early works exhibited was not fulfilled.

Death in Kazakhstan

When the German Wehrmacht invaded the Soviet Union , Vogeler, like many other artists and intellectuals who emigrated from Germany, was forcibly evacuated from Moscow to Kazakhstan by the NKVD in September 1941 . He was scheduled for execution on a special wanted list by the Nazis. His divorced wife Sonja and his son Jan , unlike him, had Soviet passports and were therefore not evacuated, but both drafted to serve in the Red Army . After a long, arduous journey, Vogeler reached the kolkhoz on May 1st in Kornejewka, Voroshilov district, Karaganda region , where he was to spend his last months. He had to work on a dam on a construction site until his strength ran out. His pension no longer reached him, and in order not to starve to death, he asked other evacuees for food. His friend, the writer Erich Weinert , transferred money for maintenance that enabled Vogeler to pay off his debts. On June 14, 1942, he died in the hospital of the "Budjonny" collective farm, probably due to a bladder problem and physical weakness. His grave is still unknown today.

In a 1989 exhibition in Worpswede, a photo was shown of the son Jan Vogeler , professor of philosophy in Moscow, at an honorary grave installed in 1986. In 1999 the city of Karaganda dedicated a memorial to Vogeler.

reception

Vogeler as a victim of the system

When asked whether the Soviet Union had a special interest in tracking the artist Vogeler, research does not provide a clear answer. The only thing that is clear is that the bureaucratic system of the Soviet Union was fundamentally indifferent to individuals. Wilhelm Pieck is said to have tried to free Vogeler from deportation, which Vogeler is said to have refused on the grounds that as long as all Germans were not treated equally, that would be out of the question for him. The system did not allow group solidarity, as the exiles were housed over thousands of kilometers.

Posthumous Autobiography Memories

The writer and friend Erich Weinert published Heinrich Vogeler's autobiography, which he began in Moscow and continued in Kazakhstan. In 1952, ten years after his death, he published Vogeler's memoirs . In the introduction, Vogeler's wish can be read: "Perhaps this book will come to people who are looking for ways to new life and who recognize in my story the wrong paths that they no longer need to commit themselves."

Perceptions

Paula Modersohn-Becker wrote to her mother in August 1897: “Another hour at Vogeler's yesterday. As always, it is a pleasure like a pretty fairy tale. He is too lovely to look at with his dream eyes. He showed us a booklet with drafts for etchings from his earliest times until now, lots of fine, original things. "

Rainer Maria Rilke, Westerwede 1902: “Some title pages in the island , the decoration of a small volume of Bierbaum's poems and the wonderful jewelry with which he surrounded the drama The Emperor and the Witch by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, confirm that his calm and line art that appears closed and yet is so rich inwardly as no other is suited to go along with the passage of noble letters like a song. "

“Vogeler was the great naive Tolstoyan among the cold bureaucrats; he left his class out of guilt; it would never have occurred to him to be critical of the new class; he believed that he no longer had the right to criticize; he did not break an oath once he had taken it; he obeyed to the point of pointlessness ”. Gustav Regulator in: The ear of Malchus. A life story , 1958

Heinrich Vogeler's son, Jan Vogeler , reports from Moscow in 1972: “When the father returned from one of his trips through the big country with hundreds of sketches and drafts, he often used to work at our little ' dacha ' near Moscow and during the breaks to tell of his experiences, of interesting people he met. Like his drawings, so was his report: clear, simple, but rich in images and lively, so that the special features of the people and things impressed on me immediately and impressively. "

Elsemarie Maletzke in the time , 15/1998: “He designed the curtains, wallpaper, furniture, glasses and cutlery. Each chair was in the place intended for it. Every rose bush in the garden knew the master. Spun on the Barkenhoff, he painted, erased, drew, wrote, 'showered' and dreamed: 'There will be some time ...' But unfortunately it turned out very differently. Art Nouveau, which at the end of the 19th century had ousted musty historicism, was itself overgrown by its fantastic mob in a few years. Vogeler went out of fashion. "

Museums and Worpsweder train station

In the Barkenhoff , where the Heinrich Vogeler Museum was opened after the renovation and restoration of the building on December 12, 2004, and in the Haus im Schluh in Worpswede, a large number of Vogeler's works are on permanent display, giving an overview of his work and his show different styles. The summer evening can be seen in the building of the Great Art Show in Worpswede, an expressionist building from the 1920s designed by the architect Bernhard Hoetger (see corresponding web links).

Worpswede train station was designed by Vogeler, inaugurated in 1910 and used as a train station until 1978. Today it is a restaurant, some of which is furnished with original furniture by the artist.

The Worpsweder archive

Martha Vogeler gave her collection of art, books and writings to the art historian Hans-Herman Rief , who has lived in Haus im Schluh since 1946 , who built it up as the “Worpsweder Archive” and brought it to the Barkenhoff Worpswede Foundation in 1981. In addition to works of art and writings by Heinrich Vogeler, Rief supplemented the collection with numerous artistic works and partial estates from Worpswede artists of the subsequent generations and created an extensive library inventory.

Plays about Vogeler

In 2000, the one-person play Heinrich Eduardowitsch was produced by the Cosmos Factory theaterproduction. Archeology of a Dream premiered in Visselhövede . The name "Heinrich Eduardowitsch" in the title goes back to the first name of the father, who was called Eduard; the artist called himself in Russia "Heinrich Eduardowitsch Vogeler". In 2003, Johann Kresniks Vogeler followed in Bremen . The Berlin author Christoph Klimke wrote the libretto for the choreographic play . It is based on Vogeler's letters, testimonials, documents and quotations, plus testimony from his son Jan, Paula Modersohn-Beckers, Ludwig Roselius and other people from the artist's environment. Torsten Ranft played the leading role, accompanied by the dancer Agniezka Samuel.

Peter von Becker wrote in Tagesspiegel on February 5, 2008 about the world premiere of Tankred Dorst's theater play Künstler in Bremen : “Tankred Dorst designed 22 scenes between Worpswede, Paris, Bremen, Moscow and the Kazakh steppe. With his usual light hand, he recounts his century theme, alternating quickly between intimate poetic sketches and figurative tableau: the aesthetic, political, social failure of a great utopia - the unity of art, love and life ”. Von Becker recalled the early round of knights in the legend about Merlin , how it broke up the Worpswede artist community. The death of the two border crossers Paula and Heinrich marks the middle and end of the play.

Novel about Vogeler

In 2015, Klaus Modick published the novel Konzert ohne Dichter about Vogeler's life in Worpswede and in particular his relationship with Rainer Maria Rilke . The title of the novel refers to the picture Summer Evening (The Concert) . The novel takes place on several time levels: the present is the day on which Vogeler drives to Oldenburg to receive the award for this picture, in flashbacks he remembers the first encounters with Rilke and his wife Martha and the early years in Worpswede.

Works (selection)

Oil paintings and etchings

- The snake bride. Etching, 1894.

- Annunciation to Mary. Etching, 1895.

- The Frog Prince. Etching, 1896.

- Spring. Oil painting, 1897.

- Winter fairy tale. Oil painting, 1897.

- The seven swans. Etching and aquatint, 1898.

- Homecoming. Oil painting, 1898.

- Farewell. Oil painting, 1898.

- Spring. Oil painting, 1898.

- Swan fairy tale. Oil painting, 1899.

- Stork over the pond. Etching, 1899.

- To spring. Portfolio with etchings. Leipzig 1899.

- Lovers. Oil painting, 1901.

- Annunciation. Oil painting, 1901.

- First summer. Oil painting, 1902.

- The concert (summer evening). Oil painting, 1905.

- Martha Vogeler. Oil painting, 1910.

- From the east. Portfolio with drawings from the war zones, 1916.

- The suffering of women in war. Oil painting, 1918.

- The seven bowls of anger. Etching, 1918.

- The Red Marie. Oil painting, 1919.

- Sonja Marchlewska. Oil painting, 1920.

- The birth of the new man. Oil painting, 1923.

- The red metropolis. Oil painting, 1923.

- Baku. Oil painting, 1927.

- Hamburg shipyard workers. Oil painting, 1928.

- The Third Empire. Oil painting, 1934.

- Mountain landscape in Kabardino-Balkaria. Oil on panel, 1940.

- Moon night. Oil on panel, 1940.

Illustrated books

- Gerhart Hauptmann , The Sunken Bell , 1898

- Heinrich Vogeler: Dir . Poems, 1899.

- Rainer Maria Rilke , Celebrating Me , 1899

- Hugo Salus , Marriage Spring , 1900

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal , The Emperor and the Witch , 1900

- Irene Forbes-Mosse , Mezzavoce , 1901

- Jens Peter Jacobsen , Niels Lyhne , 1902

- Richard Schaukal , Pierrot and Colombine , 1902

- Gerhart Hauptmann: Poor Heinrich. 1902.

- Ricarda Huch , Vita somnium breve , 1903

- Ivan Turgenev , Poems in Prose , 1903

- Irene Forbes-Mosse: Peregrina's summer evenings. undated (1904)

- Oscar Wilde : The Pomegranate House , 1904

- Irene Forbes-Mosse: The Rose Gate. 1905.

- Oscar Wilde : The Canterville Ghost and Five Other Tales , 1905

- Clemens Brentano , Spring Wreath , 1907

- Brothers Grimm , Children's and Household Tales , undated (1907)

- Otto Julius Bierbaum , My ABC , 1908

- Oscar Wilde: The Stories and Fairy Tales. Translated by Felix Paul Greve and Franz Blei , Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1910

- New edition as an island paperback: Frankfurt am Main 1972, ISBN 3-458-01705-4 .

-

Johannes R. Becher : The Third Reich , poems. Two worlds, Moscow 1934

- New edition Schütze, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-928589-05-9 .

Writings of Heinrich Vogeler

- . You poems, Leipzig 1899; New edition: Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1983 - Insel-Bücherei 981 (from 1987: IB 1072, editions Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 3-458-19072-4 and Leipzig).

- From the east. 60 war drawings from the war zones Carpathians, Galicia-Poland, Russia. Berlin 1917.

- About the expressionism of love. The way to peace. Bremen 1918.

- The new life. A communist manifesto. Hanover 1919.

- The essence of communism. The world peace. Bremen / Worpswede 1919.

- Settlement and labor school. Hanover 1919.

- Journey through Russia. The birth of the new man. Dresden 1925.

- Memories. Edited by Erich Weinert, Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1952 (autobiography, published posthumously)

- The new life. Selected writings on the proletarian revolution and art. Edited by Dietger Pforte , Darmstadt 1973.

- Fontana Martina. Complete facsimile print of the bi-monthly magazine published by Fritz Jordi and Heinrich Vogeler in 1931/1932, ed. by Dietger Pforte, Giessen 1981, ISBN 3-87038-084-5 .

- Travel pictures from the Soviet Union. 1923–1940 Ed. By Peter Elze, Worpsweder Verlag, Lilienthal 1988, ISBN 3-922516-69-6 .

- Become. Memories with testimonials from the years 1923–1942. Edited by Joachim Priewe and Paul-Gerhard Wenzlaff, Atelier im Bauernhaus, Fischerhude 1989, ISBN 3-88132-100-4 .

- Heinrich Vogeler - Between Gothic and Expressionism Debate. Writings on Art and History. Edited by Siegfried Bresler, Bremen 2006, ISBN 3-938275-09-X .

Secondary literature

- Riccardo Bavaj : Communism ideological ideology as an alternative. Heinrich Vogeler's utopia of a “new life” in the crisis discourse of the Weimar Republic. In: Journal of History. 55 (2007), pp. 509-528.

- Peter Benje: Heinrich and Franz Vogeler and the Worpsweder Werkstätte. Furniture production, workers 'village, workers' strike. With a reprint of the Worpsweder Möbel catalog based on designs by Heinrich Vogeler from 1914. Published by the Heinrich Vogeler Foundation Haus im Schluh Worpswede. Completed new edition. Worpswede 2011, ISBN 978-3-9814753-1-9 .

- Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-499-50540-1 .

- Siegfried Bresler u. a .: The Barkenhoff - Children's Home of the Red Aid 1923–1932. Worpsweder Verlag, Lilienthal 1991, ISBN 3-922516-91-2 .

- Siegfried Bresler: In the footsteps of Heinrich Vogeler. Schünemann Verlag, Bremen 2009, ISBN 978-3-7961-1925-5 .

- Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler - life stations . Schünemann Verlag, Bremen 2017, ISBN 978-3-96047-016-8 .

- Tankred Dorst , Ursula Ehler : artist. One piece. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-518-12515-1 .

- Herbert Eichhorn , Rena Noltenius: Heinrich Vogeler. From Worpswede to Moscow. Catalog for the exhibition of the same name in the Städtische Galerie Bietigheim-Bissingen July 12 to September 21, 1997. City of Culture and Sports Office, Bietigheim-Bissingen 1997, ISBN 3-927877-28-X .

- Peter Elze: Heinrich Vogeler. Book graphics. The catalog raisonné 1895–1935. Worpsweder Verlag, Lilienthal 1997, ISBN 3-922516-74-2 .

- David Erlay: Heinrich Vogeler and his Barkenhoff. Atelier in the farmhouse, 1979, ISBN 3-88132-125-X .

- David Erlay: From gold to red. Heinrich Vogeler's way into another world. Donat Verlag, Bremen 2004, ISBN 3-934836-74-7 .

- Walter Fähnders, Helga Karrenbrock: “Communist Rose Cutting”. To the avant-garde Heinrich Vogeler on the 140th birthday and the 70th anniversary of his death. Dossier. In: opponents. (Berlin) H. 31 (2013), pp. 18–31. ISSN 1432-2641 .

- Henrike Hans, Kai Hohenfeld: Art Nouveau in Bremen. Heinrich Vogeler's drafts for the Güldenkammer [catalogs of the Kupferstichkabinett, Volume 5], Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-3-935127-23-3 .

- Wulf D. Hund : Heinrich Vogeler. Hamburg shipyard workers. From the aesthetics of resistance. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-596-10742-3 .

- Ilse Kleberger : One and the other dream. The life story of Heinrich Vogeler. Beltz Verlag, Weinheim / Basel 1991, ISBN 3-407-80696-5 .

- Bernd Küster: Heinrich Vogeler in the First World War. (= Catalogs of the State Museum for Art and Cultural History Oldenburg; Volume 21). Donat Verlag, Bremen 2004, ISBN 3-934836-83-6 .

- Ernst Meyer-Stiens: Sacrifice for what? German emigrants in Moscow - their life and fate . Worpsweder Verlag, Lilienthal 1996, ISBN 3-89299-184-7 . A book about the 5th Heinrich Vogeler Symposium 1995 in Lilienthal-Worphausen.

- Klaus Modick : Concert without a poet . Novel. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2015, ISBN 978-3-462-04741-7 .

- Reinhard Müller : From the Moscow cadre file of the non-party Bolshevik Heinrich Vogeler. In: Journal Exil - Research, Findings, Results. Born 1995, issue 1.

- Theo Neteler: The book artist Heinrich Vogeler. With a bibliography. Antinous-Ed. Matthias Loidl, Ascona a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-930552-00-0 .

- New society for fine arts : Heinrich Vogeler. Works of art - objects of daily use - documents. Frölich & Kaufmann, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-88725-014-1 . (Exhibition in the Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin and Kunstverein Hamburg 1983)

- Rena Noltenius: Heinrich Vogeler. 1872-1942; the paintings - a catalog of works. VDG, Weimar 2000, ISBN 3-89739-020-5 . (partly including dissertation; University of Tübingen)

- Heinrich Wiegand Petzet: Heinrich Vogeler drawings. Worpsweder Archive, 1967.

- Heinrich Wiegand Petzet: Heinrich Vogeler. From Worpswede to Moscow. An artist between times. DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1972, ISBN 3-7701-0636-9 .

- Hans-Herman Rief : Heinrich Vogeler. The graphic work. New edition. Worpsweder Verlag, Worpswede 1983, ISBN 3-922516-34-3 .

- Rainer Maria Rilke: Worpswede: Fritz Mackensen, Otto Modersohn, Fritz Overbeck, Hans at the end, Heinrich Vogeler. 10th edition. New edition Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-458-32711-0 .

- Sabine Schlenker, Beate Ch. Arnold (Ed.): Heinrich Vogeler: Artist - Dreamer - Visionary . Catalog for the exhibition in Worpswede. Hirmer, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7774-4991-3 .

- Bernd Stenzig: Heinrich Vogeler. A Bibliography of the Scriptures. (= Barkenhoff Foundation series of publications, No. 28). Worpsweder Verlag, Lilienthal 1994, ISBN 3-89299-177-4 .

- Bernd Stenzig: The fairy tale about God. Heinrich Vogeler's peace appeal to the Kaiser in January 1918. Friends of Worpswedes Association, Worpswede 2014

- Michael Baade : Jan Vogeler - son of the painter Heinrich Vogeler. With pictures and letters from Heinrich Vogeler. Kellner Verlag, Bremen 2020, ISBN 978-3-95651-243-8

- Vogeler, Heinrich Joh. In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General encyclopedia of fine artists from antiquity to the present . Founded by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker . tape 34 : Urliens – Vzal . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1940, p. 419 .

- Vogeler, Heinrich . In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General Lexicon of Fine Artists of the XX. Century. tape 5 : V-Z. Supplements: A-G . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1961, p. 47 .

- Vogeler, Heinrich (Johann) . In: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945 . 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Karl Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

Exhibitions

- 1955: First German post-war exhibition at the Great Art Show in Worpswede. Vogeler's works from the Soviet Union will be shown for the first time.

- 1972: Memorial exhibition on the occasion of the 100th birthday, Worpsweder Kunsthalle

- 1979: Riccar Art Museum, Tokyo

- 1982: Kunstverein Bonn

- 1983: State Art Gallery Berlin and Art Association in Hamburg

- 1996: Art 1900, Berlin; Gallery tongue, Berlin

- 1997: Municipal Gallery Bietigheim-Bissingen

- 1997–1999: Barkenhoff, Große Kunstschau, Haus im Schluh Worpswede - December 12, 1997 - May 24, 1998 + Museum Künstlerkolonie Darmstadt - June 20 - September 6, 1998 + Gustav-Lübcke-Museum, City of Hamm - October 25, 1998 - January 11, 1999: Heinrich Vogeler and the Art Nouveau , catalog, ISBN 3-7701-4041-9 and book trade, ISBN 3-7701-4040-0 .

- 2002: Barkenhoff Foundation Worpswede: "Primarily house building - Heinrich Vogeler and the reform architects from Bremen"

- 2007/2008: “An artist friendship - Heinrich Vogeler and Paula Modersohn-Becker” - Haus im Schluh, Worpswede

- 2012: “Heinrich Vogeler. Artists, dreamers, visionaries "- summer exhibition of the Worpsweder museums (Barkenhoff / Heinrich Vogeler Museum, Great Art Show Worpswede, Haus im Schluh / Heinrich Vogeler Collection, Worpsweder Kunsthalle)

- 2015: artists and prophets. A secret history of modernism 1872–1972 , including Vogeler is depicted. Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

Films, plays (selection)

- 1984: Heinrich Vogeler - Pictures of Life. Film of the North German Radio, Hamburg, by Georg Bühren

- 1991: Distorted gaze. The ideologization of art using the example of Heinrich Vogeler. Film of the Bavarian Radio, Munich, by Sibylle Wagner

- 2003: World premiere of Johann Kresnik's Vogeler at the Bremen Schauspielhaus

- 2008: World premiere of Tankred Dorst's artist at the Neuen Schauspielhaus Bremen

Web links

- Literature by and about Heinrich Vogeler in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Heinrich Vogeler in the German Digital Library

- Search for Heinrich Vogeler in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Website of the Barkenhoff Foundation with the Heinrich Vogeler Museum in Worpswede

- Website of the Heinrich Vogeler Society on Heinrich Vogeler

- Haus im Schluh on worpswede-museen.de

- Heinrich Vogeler on kunstaspekte.de

- Differences in Heinrich Vogeler's works before and after the change of style

- Rainer Maria Rilke on Vogeler

- Jan Vogeler about his father Heinrich on July 2, 2003 in Welt Online

- Theater play Vogeler by Johann Kresnik, 2003

- Theater play artist by Tankred Dorst, 2008 ( Memento from July 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Reviews by Nicola Hille with Heinrich Vogeler's curriculum vitae

- Walter Fähnders: On the 140th birthday and 70th anniversary of the death of avant-garde Heinrich Vogeler 2012 on literaturkritik.de , July 7, 2012

- Heinrich Vogeler Archive in the Archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

Individual evidence

- ^ Heinrich Wiegand Petzet: Heinrich Vogeler - drawings. dumont art pocket books, Cologne 1976, p. 193.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. P. 18 f.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. Pp. 24-27.

- ^ Heinrich Vogeler: Becoming. P. 49.

- ↑ Alex Koch (Ed.): German Art and Decoration, Bad IV, April 1899 - September 1899, JC Herbert'sche Hofbuchdruckerei, Darmstadt, pp. 293–309, exhibition in Dresden, p. 332 digitized PDF

- ^ Goldoni, Maria: "A Stollwerck series by Heinrich Vogeler and Franz Eichert" in Esslingen conference proceedings 2002, Working Group Image, Print & Paper.

- ^ Paul Cassirer (Ed.): Catalog of the seventh art exhibition of the Berlin Secession, 1903 , in III. Directory of members of the Berlin Secession. P. 47, currently in Rome, Villa Strohl-Fern, Rome ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler in Italy In: Heimat-Rundblick from the region Hamme, Wümme, Weser - history, culture, nature. No. 116, spring 2016 ( [1] PDF).

- ^ Paul Cassirer (ed.): Catalog of the seventh art exhibition of the Berlin Secession, 1903. In: I. Oil painting. P. 34 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Exhibition catalog X. Exhibition of the Munich Secession: The German Association of Artists (in connection with an exhibition of exquisite products of the arts in the craft). Publishing house F. Bruckmann, Munich 1904 (p. 32: Vogeler, Heinrich, Worpswede. Catalog No. 168: Annunciation , with illustration in the picture section).

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. Pp. 32-35.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. P. 46 f.

- ^ Heinrich Vogeler: Memories. P. 161.

- ^ The Worpswede painters of the founding generation , worpswede-museen.de, accessed on March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Heinrich Vogeler , martinschlu.de, accessed on January 3, 2012 found.

- ^ Matthias Gretschel: Heinrich Vogeler - A summer evening in Worpswede , abendblatt.de, June 25, 2012, accessed on January 10, 2013.

- ^ From Art Nouveau to Prolet Art , report by Rainer Berthold Schossig on Deutschlandfunk Online from December 12, 2007.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. P. 72 ff.

- ^ Karen E. Hammer: Vogeler - Roselius - Hoetger. A triumvirate between friendship and artistic acceptance. In: Heimat-Rundblick. History, culture, nature . No. 102, 3/2012 ( autumn 2012 ). Druckerpresse-Verlag , ISSN 2191-4257 , pp. 12-14.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler, p. 69.

- ↑ Institute for Syndicalism Research :. Article on Heinrich Vogeler, accessed April 6, 2015 .

- ^ Heinrich Vogeler: The work school. In: freedom. Organ of the Berlin USPD. Vol. 4, No. 561, December 1, 1921.

- ^ Zofia Marchlewska: A wave in the sea. Memories of Heinrich Vogeler and contemporaries . Book publisher Der Morgen, Berlin (East) 1968.

- ^ Heinrich Vogeler: Journey through Russia. Dresden, undated [1925], p. 5.

- ↑ David Erlay: From gold to red. Heinrich Vogeler's way into another world. P. 404 f., 408 f.

- ↑ The meeting between Heinrich Vogeler and Diego Rivera was testified by Ella Ehlers, the director of the Barkenhoff children's home, in an interview.

- ↑ David Erlay: From Gold to Red. P. 370 f.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Ernst Behm - Life Path of a Political Pedagogue, in: Päd extra - Democratic Education, Issue 1, Wiesbaden January 1991, pp. 42–45

- ^ Jungclas, Georg , in: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945 . 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Karl Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- ↑ Behm was under police surveillance; a file on this is in the Stade State Archives: Rep 174 Osterholz Fach 1 / No. 20 - about the Barkenhoff teacher Ernst Behm

- ↑ The drum. Journal for workers and farmers' children in the catalog of the German National Library . The magazine was published by the Berliner Verlag Junge Garde from 1926 to 1933 and was the successor to the magazine Jung Spartakus .

- ↑ Helmut Schinkel (born October 14, 1902 in Kosten , † May 31, 1946 in an NKVD camp) was a teacher and educator at the Barkenhoff children's home. In 1932 he became director of the Karl Liebknecht School (Moscow) . In 1938 he was sentenced to eight years in a labor camp and died there in 1946. A detailed biography of Helmut Schinkel comes from Ulla Plener : Helmut Schinkel: Between Vogeler's Barkenhoff and Stalin's camp. Biography of a reform pedagogue (1902-1946) , Trafo-Verlag, 2nd edition, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-89626-142-8 & Helmut Schinkel , in: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945 . 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Karl Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- ↑ Folk songs archive: Barkenhofflied . There you can also find the complete text as well as a video of the group Die Grenzgänger , who perform the song. A version sung by a children's choir can be found on youtube: Barkenhoff Abendlied . The song is highlighted there with a lot of historical images.

- ^ Helmut Schinkel , in: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945 . 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Karl Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- ↑ For a detailed history of the Barkenhoff children's home see: Der Barkenhoff, Children's Home of the Red Aid 1923 - 1932. A documentation on the exhibition at Barkenhoff 1991 , Worpsweder Verlag 1991, ISBN 978-3-922516-91-0

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. P. 98.

- ↑ David Erlay: From Gold to Red. P. 415 ff.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. Pp. 107, 110.

- ↑ Reinhard Müller: From the Moscow cadre file of the non-party Bolshevik Heinrich Vogeler . In the journal Exil - research, knowledge, results . JG 1995, No. 1, pp. 34-39.

- ^ Siegfried Bahne: Using the example of the KPD - The persecution of German communists in Soviet exile. In communists, communists persecute: Stalinist terror and purges in the communist parties of Europe since the 30s . Edited by Hermann Weber; Dietrich Staritz; Siegfried Bahne; Richard Lorenz, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-05-002259-0 (Contributions to the International Symposium at the University of Mannheim White spots in the history of world communism, Stalinist terror and purges in the communist parties of Europe since the 1930s , February 1992, p. 241 .)

- ↑ Jan Vogeler / Heinrich Fink: Heinrich Vogeler and the Utopia of the New Man (PDF; 69 kB), rosalux.de, accessed on January 10, 2013.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. P. 128.

- ↑ Petra Kipphoff: The consequent dreamer - an artist, captured by the province and the party in Die Zeit , August 5, 1989, for an exhibition about Vogeler in Worpswede

- ↑ Lemma Vogeler, Heinrich (Johann) . In: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst: German Communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945. 2., revised. and strong exp. Edition. Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 . Online version

- ↑ Klaus von Beyme: The age of the avant-garde: Art and society 1905–1955. Beck, Munich 2005, p. 810, accessed on July 16, 2010 .

- ^ Heinrich Vogeler: Memories. P. 17.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler. P. 138.

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke: Complete Works. Volumes 1-6, Volume 5, Wiesbaden / Frankfurt am Main 1955-1966, pp 117-134. on Zeno.org (accessed February 3, 2008)

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler p. 139.

- ^ Siegfried Bresler: Heinrich Vogeler p. 139.

- ^ Elsemarie Maletzke: entwined world in: Die Zeit , issue 15, 1998.

- ^ The Worpswede archive of the Barkenhoff Foundation Worpswede. www.worpswede-museen.de, accessed on August 12, 2015.

- ↑ Current plays about Vogeler , literaturatlas.de, accessed on January 8, 2013.

- ↑ Peter von Becker: The legend of Heinrich and Paula. Der Tagesspiegel , February 5, 2008, accessed December 20, 2010 .

- ^ First summer oil painting, 1902, Kunsthalle Bremen ( Memento from April 17, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vogeler, Heinrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Vogeler, Johann Heinrich (full name); Vogeler-Worpswede, Heinrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter, graphic artist, architect, designer, educator, writer and socialist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 12, 1872 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bremen |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 14, 1942 |

| Place of death | Karaganda , Kazakh SSR |