Leberecht Migge

Leberecht Migge (born March 20, 1881 in Danzig ; † May 30, 1935 in Flensburg ) was a German landscape architect and author. He was one of the most influential garden architects of the early 20th century in German-speaking countries.

Life

Leberecht Migge grew up as the eighth of twelve children in a Gdansk merchant family. After a horticultural apprenticeship from 1898 and his first practical experience in Hamburg, he was there from 1904 onwards, at one of the first large German landscaping companies, Jacob Och's artistic director. He quickly developed from a handicraft and technical gardener to a green designer.

In 1910 he went on a study trip through England. From 1913 Leberecht Migge worked as a freelancer in Hamburg- Blankenese and laid out his own garden. He had already joined the German Werkbund in 1912 . Supported by the contacts he made and the planning of various public parks, Migge developed his own theory of the role and function of landscape architecture. He published his ideas in books such as "The garden culture of the 20th century" (1913) and "Jedermann Selbstversorger " (1918). Here he presented his ideas about the social functions of urban green space and developed the idea of the garden city from England into his own model. In his opinion it should be possible to develop cities into “autonomous beings” without exploiting the surrounding landscape.

Worpswede

Migge had lived in the Worpswede artists 'colony since 1920 and initially tried to realize his ideas here in the “ Sonnenhof ” project and beyond through his work for the Anhalt settlers' association under the direction of Leopold Fischer . For the settlers' association he planned, among other things, the gardens in the experimental settlements “ Dessau-Ziebigk ”, “ Hohe Lache ” and in Dessau-“ Kleinkühnau ”. It is typical of Migge's kitchen gardens that all gardens in a settlement follow the same pattern and are distinguished by rhythmic accents such as fruit trees. In accordance with his social reform concerns, the gardens were equipped with trellises , composting toilets and gazebos .

The artistic engagement with the zeitgeist determined by the Heimatschutz movement and the Volkspark movement led Leberecht Migge and artists such as Bernhard Hoetger and Heinrich Vogeler to the social reform model of the “labor commune”. In this project, the dovetailing of gardening, agriculture and attached workshops was tested with the aim of merging hand and brain work in art. For this purpose Migge had leased the “Moorhof” in Worpswede from the sculptor Bernhard Hoetger in return for payment with products from the farm.

In the 1920s and 1930s Leberecht Migge designed many outdoor facilities for the “ New Building ” movement that emerged during the “Weimar Republic ”. During this time he worked with architects such as Otto Haesler ( Georgsgarten , Celle ), Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner ( Hufeisensiedlung , Berlin-Britz , Neukölln district ; Waldsiedlung Berlin-Zehlendorf ).

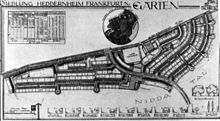

Together with Ernst May and the Frankfurt horticultural director Max Bromme , he designed the transition from the Frankfurt core city to the new settlements in the periphery. The gardens and green spaces of the Römerstadt settlement are a well-known example of this collaboration on the New Frankfurt project .

Sunny island

In 1931, Migge leased the island of Dommelwall from the Köpenick district in southeast Berlin. The lease was renewed or extended in 1933. In terms of landscape, the island belongs to the Gosen swamp area, it is predominantly swampy. He had the northern part of the island dumped with rubbish in 1932/33. To do this, he signed a contract with a Berlin waste disposal company. In the northern part of the island a small footbridge was created, on the west side there is a small lawn for sunbathing. Also in the north-eastern part is the house built by Migge.

On the " sun island " - named after the Sonnenhof in Worpswede - Migge lived with Liesel Elsässer, the wife of Martin Elsaesser . Later, people from Migge's circle of friends and the Elsässer family lived and stayed there in order to avoid the bombing raids of World War II. 1945-46 the island was plundered several times by Soviet soldiers and then abandoned by the residents. Migge's idea was to test a self-sufficient circular economy on the island. This project and the relationship between Migge and Liesel and Martin Elsaesser is the subject of the 2017 documentary Die Sonneninsel, directed by Thomas Elsaesser , Martin Elsaesser's grandson, in collaboration with the Martin Elsaesser Foundation .

National Socialism

After sympathizing with communism for a long time, he became enthusiastic about National Socialism in 1932 . As a result, he isolated himself from his long-term friends and partners in the New Building sector. At the same time, he was suspicious of representatives of Nazi garden design as a leftist and ex-communist. Migge's attempts to ingratiate himself with the Nazi ideology in his later writings were also unsuccessful.

Migge died in 1935 of kidney disease. In Wilhelmshaven and in Frankfurt am Main, Riedberg district, streets are named after him.

Reception and significance for the present

The ideas strongly represented by Leberecht Migge made him a "lone fighter" among his colleagues, although many of his ideas were adapted to the social situation of his time and were shared by them in individual aspects.

With his work, Migge stands in the tradition of the reform efforts in urban housing and urban planning that began in the second half of the 19th century , which ultimately led to the garden city movement at the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, the municipalities were increasingly responsible for the design of the open space. Functional concepts such as the distinction between “sanitary” and “decorative” green ( Camillo Sitte ) and Martin Wagner's open space theory were conducive to this . However, these tendencies only intensified under the changed socio-political framework conditions of the Weimar period . With the growing importance of public green spaces, new design options opened up for private green spaces that corresponded to new forms of construction and settlement. The ratio of indoor living space to outdoor living space has become a characteristic distinguishing feature of various architectural trends and their protagonists .

Since the garden architect profession traditionally worked for a middle-class clientele, the new endeavors to design open spaces in multi-storey apartment building were slow to gain acceptance . In 1927, an employee of the architect Ernst May was outraged to discover: "It was as if there were only castles and ornamental parks in Germany and not thousands of people who would also like to have a garden of beauty on a small piece of earth." It is therefore not surprising that that Leberecht Migges' work in the field of new building in multi-storey housing appeared from the point of view of the time as that of an outsider of his guild. Migge designed a variety of usage- oriented concepts in public space, such as play areas for children , communal roof gardens , relaxation areas for the elderly or garbage disposal .

Migges was particularly interested in the privately usable garden, which served as "extended living space". This concept was developed before the First World War, but he further developed it for serial application. Migge himself: "The goal of garden industrialization is to provide everyone with a garden, a technically good garden."

Another focus of Migges was his social reform efforts to enable the disadvantaged population groups to be self-sufficient. These efforts go back to before the First World War. In this area Migge was an outstanding proponent of these ideas through his journalistic impact. An examination of the economic efficiency showed, however, that the introduction of the garden type he had developed was hardly sustainable. Through these endeavors, Migge nevertheless played a large part in turning garden architecture towards petty-bourgeois and proletarian interests.

The share of Leberecht Migges in the buildings of classical modernism is controversial . By granting the social and economic benefits of the house garden a dominant position in house construction, Migge was exactly the opposite of what the Bauhaus wanted: the open space, like the building, should be strict, simple and functional. Walter Gropius, the most influential architect of the Bauhaus, did not allow free space to have any influence on house construction.

Migge's idea that everyone should be able to provide for themselves and that they must have their own house and garden autonomously was taken up again in the 1970s by the Kassel School of Landscape and Open Space Planning and further developed: autonomy in use, which is or is possible in open space planning should at least not be prevented.

Honors

- The Leberecht Migge facility in Frankfurt-Kalbach-Riedberg was named after him in April 2013.

Works (selection)

- 1908/09: The "Alster" from Roggendorf (Mecklenburg) , client: Carl von Haase

- 1910: Wacholderpark in Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel , laid out as a “public garden”

- 1913: Park on Freedom Square (today: Slovanské náměstí) in Brno

- 1913–1914: Mariannenpark in Leipzig-Schönefeld

- 1914–1918: Rüstringer City Park and Cemetery of Honor in Wilhelmshaven

- 1918–1921: Garden monument in the Berlin-Schöneberg settlement Lindenhof not far from Alboinplatz

- 1924: Resting place for the victims of the revolution in the Eichhof park cemetery in Kiel

- 1927–1933: Horseshoe settlement in Berlin-Britz (in cooperation with Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner)

Publications

- Hamburger garden furniture. Jakob Ochs Horticulture. Hamburg 1910. ( digitized version )

- The garden culture of the 20th century. Diederichs, Jena 1913. (Reprint: GhK, Department of Urban Planning and Landscape Planning, Kassel 1983), ( digitized version )

- Everyone self-sufficient! A solution to the settlement question through new horticulture. Diederichs, Jena 1918, ( digitized version )

- The productive settlement lodge. Intensive settler school based on self-help. Diederichs, Jena 1920.

- German internal colonization. Material foundations of the settlement system . Ed .: German Garden City Society Berlin-Grünau, Deutscher Kommunal-Verlag, Berlin 1926.

- The social garden. The green manifesto. Berlin-Friedenau 1926. (Reprint: Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-7861-2291-1 )

- The growing settlement according to biological laws , Franckh, Stuttgart 1932.

literature

in chronological order

General

- Martin Baumann: Rationalism in the Park. Leberecht Migge's conception for the Volkspark . In: Die Gartenkunst 32 (1/2020), pp. 175–191.

- Martin Baumann: Planning by garden architect Leberecht Migge for the open spaces of settlements . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 2/2019, pp. 267–290.

- Thomas Elsaesser : "Like a lofty master in Adam's costume": the late Migge and the beginnings of the "sunny island" . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 267–290. Pp. 315-326.

- Heiko Grunert: Leberecht Migge. Spartacus in green, of whom the red is to die. In: Die Gartenkunst, February 31, 2019, pp. 175–191.

- David H. Haney: Life and Work of Leberecht Migge in International Contexts . In: Die Gartenkunst, February 31, 2019, pp. 291–306.

- Stefanie Hennecke : Leberecht Migge's parks and his contribution to the city park discussion in Hamburg . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 237–250.

- Klaus Hoppe: A “public garden” in Fuhlsbüttel . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 333–336.

- Ursula Keller: "A pike in a carp pond". Leberecht Migge and the garden architects of his time . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 221–236.

- Jörg Schilling: "The intellectual situation between garden and house remains difficult". Migge and the structural architects of his time . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 175–191. Pp. 209-220.

- Sophie von Schwerin: Migge`s garden plans for the city - examples from the plan volume in the archive for Swiss landscape architecture . In: Die Gartenkunst 31. 2/2019, pp. 307–314.

- Christiane Sörensen: WasserHorizonte VIII - Migge 2019 . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 337–343.

- Barbara Uppenkamp: The Sonnenhof and the settler school in Worpswede . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 251–266.

-

Garden art 31 (2/2019):

- Galia Bar Or: “Overcoming Artificial Divisions”: The City-Village Kibbutz , pp. 327-332.

- Hansjörg Gadient, Sophie von Schwerin, Simon Orga: The original landscape designs / The original garden plans 1910–1920 , Birkhäuser, Basel 2019. ISBN 978-3-0356-1359-9

- Lutz Oberländer : The departure into the modern age. The "New Jerusalem" settlement by Erwin Gutkind and Leberecht Migge. disserta, Hamburg 2016. ISBN 978-3-95935-333-5

- David H. Haney: Birds and fish versus potatoes and cabbage: Max Bromme, Leberecht Migge and the green space planning in the New Frankfurt . In: Claudia Quiring, Wolfgang Voigt, Peter Cachola Schmal, Eckhard Herrel (eds.): Ernst May 1886–1970 . Prestel, Munich 2011. ISBN 978-3-7913-5132-2 , pp. 69-78.

- Johannes Rosenplänter: On the origin of the 'resting place of the victims of the revolution' on the Eichhof cemetery in Kiel 1918–1924. A work by the landscape architect Leberecht Migge . In: Rolf Fischer (ed.), Revolution and Revolutionsforschung - Contributions from the Kiel Initiativkreis 1918/19 = special publications by the Society for Kiel City History 67. Ludwig, Kiel 2011. ISBN 978-3-86935-059-2

- Gert Gröning: The Alster from Roggendorf. Leberecht Migge and the Haase Park. A view from a hundred years away. In: Bernfried Lichtnau (ed.): Fine arts in Mecklenburg and Pomerania from 1880 to 1950 . Berlin 2011, pp. 497-517.

- David H. Haney: When Modern Was Green. Life and Work of Landscape Architect Leberecht Migge . Routledge, London / New York 2010. ISBN 978-0-415-56139-6

- Martin Baumann: Open space planning in the settlements of the twenties using the example of the planning of the garden architect Leberecht Migge = dissertation, University of the Arts Berlin 2001. Trift, Halle 2002. ISBN 3-934909-13-2

- Karin von Behr: Migge, Leberecht . In: Franklin Kopitzsch, Dirk Brietzke (Hrsg.): Hamburgische Biographie . tape 1 . Christians, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-7672-1364-8 , pp. 206 .

- Ita Heinz-Greenberg: “News from Migge”: The self-sufficiency concept for Eretz Israel . In: Die Gartenkunst 10 (1/1998), pp. 135–143.

- Michael Rohde: A people's park of the 20th century in Leipzig by Migge and Molzen . Park maintenance for the Mariannenpark . In: Die Gartenkunst 8 (1/1996), pp. 75-107.

- Jürgen von Reuss: Migge, Leberecht. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 17, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-428-00198-2 , p. 488 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Christine Ahrend: The importance of the democratic planning approaches of the twenties for the emancipatory planning of the present. In: Ulrich Eisel, Stefanie Schultz (ed.): History and structure of landscape planning = series: landscape development and environmental research . No. 83. TU, Univ.-Bibliothek, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-7983-1461-6 , pp. 247-278.

- Ralf Krüger and Cord Panning: The Schelploh Park. A previously unknown garden monument by Fritz Encke and Leberecht Migge . In: Die Gartenkunst 3 (2/1991), pp. 307-318.

- Helmut Böse, KH Hülbusch: Cotoneaster and plaster. Plants and vegetation as design elements . In: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Freiraum und Vegetation (Ed.): Review of open space planning . Arbeitsgemeinschaft Freiraum und Vegetation, Kassel 1989, pp. 23–32.

- Helmut Böse-Vetter: Migge in a refill pack. Notes from current events . In: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Freiraum und Vegetation (Ed.): Review of open space planning . Arbeitsgemeinschaft Freiraum und Vegetation, Kassel 1989, pp. 16–23.

- Inge Meta Hülbusch: “Everyone is self-sufficient”. The colonial green Leberecht Migges . In: Lucius Burckhardt (ed.): The Werkbund in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Shape without ornament . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1978. ISBN 3-421-02529-0 , pp. 66–71

Bibliographies

- Annette Grunert, Heino Grunert: Bibliography on Leberecht Migge . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 344–362.

- Heidrun Hubenthal (ed.): Bibliography on Leberecht Migge. Finding aid for the Leberecht Migge Archive . Information system planning, Univ., Kassel 2004, ISBN 3-89117-140-4

Catalog raisonnés

- Sophie von Schwerin: Leberecht Migge - project list . In: Die Gartenkunst 31 (2/2019), pp. 363–371.

Web links

- Literature by and about Leberecht Migge in the catalog of the German National Library

- Image index

- Gardens of the Frankfurt-Heddernheim housing estate, as it was in the early 1930s

- The sunny island

Individual evidence

- ^ Verlag Architektur und Technik, Gartenarchitektur, Jedermann ein Garten

- ^ Gert Gröning, Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn: Green biographies. Patzer-Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-87617-089-3 , p. 261.

- ↑ Paul Thiecke, A kindergarten of liver Migge, decoration and art, 1917, 273

- ↑ Elsaesser: "Like a noble master ..." .

- ↑ "Islands of Image Evidence. Die Sonneninsel am Seddinsee 1935–44 “ In: bildevidenz.de , accessed on February 14, 2018.

- ↑ Elsaesser: "Like a noble master ..." .

- ↑ Kay Hoffmann: The sunny island . Further information on the film can be found in English on The Sun Island website . The film can be obtained as a DVD from the Martin Elsaesser Foundation's homepage.

- ↑ Inge Meta Hülbusch 1978; Helmut Böse and Karl-Heinz Hülbusch 1980; Helmut Böse-Vetter 1989; Christine Ahrend 1992

- ↑ Official Journal for Frankfurt am Main , Volume 144, No. 17, City of Frankfurt am Main, April 23, 2013.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Migge, Leberecht |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German garden architect and garden author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 20, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Danzig |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 30, 1935 |

| Place of death | Worpswede |